CORRUPTION UNDER SUHARTO

Suharto and his regime were very corrupt. Transparency International has since identified Suharto—who is estimated to have embezzled more than $30 billion—as one of the most corrupt leaders in modern history. During his years in power, corruption, mismanagement, cronyism and nepotism were the norm. Suharto concealed his wealth with he help of Indonesia's lax financial disclose laws and used the national treasury as his own bank account to dispose loans to cronies and engage in shady business deals. Some rank him with the Philippines’ Ferdinand Marcos and Zaire's Mobutu Sese Seko for amount of money he skimmed from the national treasury to fill his pockets and those of his friends and relatives. The whole system of government was described as a kleptocracy.

Maggie Farley wrote in the Los Angeles Times: Under Suharto the Indonesian economy was “a system ground in nepotism, sanctioned skimming and economic dislocation. This arrangement—where a Suharto family member of friend acts as the overlord of an industry, squeezing out all competition—has been relocated dozens f times throughout Indonesia. Corruption was rife at all levels of society, and Indonesian business culture came to revolve around kickbacks and bribes. The most obvious recipients of the new wealth were Suharto’s business associates and his family. They acquired huge business empires, along with prime government contracts.”

Through the 1970s and 1980s, Indonesia's pervasive corruption became a political issue that the New Order state could not entirely muffle. In January 1974, the visit of Japanese prime minister Tanaka Kakuei sparked rioting by students and urban poor in Jakarta. Ostensibly fueled by resentment of Japanese exploitation of Indonesia's economy, the so-called "Malari Affair" also expressed popular resentment against bureaucratic capitalists and their cukong associates. During the 1980s, the ties between Suharto and Chinese entrepreneur Liem Sioe Liong, one of the world's richest men, generated considerable controversy. The Liem business conglomerate was in a favored position to win lucrative government contracts at the expense of competitors lacking presidential ties. Import licenses were another generator of profits for well-connected businessmen. The licensing system had been established to reduce dependence on imports, but in fact it created a high-priced, protected sub-economy that amply rewarded license holders but reduced economic efficiency. By 1986 licenses were required for as many as 1,500 items. Foreign journals also published reports concerning the rapidly growing business interests of Suharto's children. [Source: Library of Congress]

John Gittings wrote in The Guardian, in the 1990s the “biggest source of dissent was a huge growth in cronyism and the blatant pursuit of financial gain by the Suharto family. Such nepotism was not essential for the Suharto regime — it reflected his adoption of a ruling style increasingly akin to that of a traditional Javanese king. The village in which he had been born was graced with a palace, and it was ordained that he should be buried in the nearby family mausoleum, echoing the royal custom of hilltop interment. [Source: John Gittings, The Guardian, January 27, 2008]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUHARTO: HIS LIFE, PERSONALITY AND RISE TO POWER factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER SUHARTO: NEW ORDER, DEVELOPMENT, FOREIGN POLICY factsanddetails.com

REPRESSION UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: KILLERS, VICTIMS, REASONS factsanddetails.com

1997-98 ASIAN FINANCIAL CRISIS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998: PRESSURES, EVENTS, RESIGNATION factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO AFTER HIS RESIGNATION: TRIALS, DEATH, LEGACY, VIEWS, FAMILY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO AS PRESIDENT: CHALLENGES, AUTHORITARIANISM, GUIDED DEMOCRACY factsanddetails.com

Oil Money and Corruption in Indonesia

The oil boom in the 1970s provided unprecedented opportunities for corruption. Pertamina was established in 1968 as a merger of Permina and two other firms. Its director, General Ibnu Sutowo, a hardy survivor of the transition from Guided Democracy to New Order who had been director of Permina, embarked on an ambitious investment program that included purchase of oil tankers and construction of P.T. Krakatau, a steel complex. In the mid-1970s, however, it was discovered that he had brought the firm to the brink of bankruptcy and accrued a debt totaling US$10 billion. In 1976 he was forced to resign, but his activities had severely damaged the credibility of Indonesian economic policy in the eyes of foreign creditors. *

The Pertamina affair revealed the problems of what Australian economist Richard Robison, in a 1978 article, called Indonesia's system of "bureaucratic capitalism": a system based on "patrimonial bureaucratic authority" in which powerful public figures, especially in the military, gained control of potentially lucrative offices and used them as personal fiefs or appanages, almost in the style of precolonial Javanese rulers, not only to build private economic empires but also to consolidate and enhance their political power. Because Indonesia lacked an indigenous class of entrepreneurs, large-scale enterprises were organized either through the action of the state (Pertamina, for example), by ethnic Chinese capitalists (known in Indonesia as cukong), or, quite often, a cooperative relationship of the two. *

Suharto’s Wealth

Suharto amassed of fortune while in office estimated at $4 billion in 1999 by Forbes magazine,$15 billion by the New York Times, and $45 billion by the Wahid government. In 2008, the United Nations and the World Bank put Suharto top of the world's most corrupt leaders, quoting a Transparency International estimate that he embezzled up to $25 billion. Transparency International estimated Suharto’s worth at between $15 to $30 billion.

When he came to power, Sharto refused at first to move into the presidential palace, saying he preferred to live in his own modest house in Jakarta. But as time went on his homes became more numerous and palatial. At one time Forbes listed Suharto as the sixth wealthiest person in the world with a net worth of $16 billion. This was not bad for a man who reportedly earned around $21,000 a year as president and resided in a modest bungalow in a Jakarta suburb and drove a 1964 Ford Galaxy after he first became president.

Suharto had a great deal of power over almost every sector of the economy and he had so many palace-like retreats that it was not that unusual just to stumble across them. Suharto reportedly began amassing wealth in 1966, before he became president, when he issued a decree to seize control of Sukarno-owned conglomerates worth $2 billion. Over the years his fortune grew along with those of his cronies Liem Sioe Liong of the Salim Group and Mohammed "Bob" Hassan.

Suharto said, "The fact is I don't have one cent of savings abroad, let alone hundreds of millions...the rumors are not true." He claimed his only assets were 19 hectares of land and $2.4 million in savings. Time reported that in July 1998, two months after Suharto reigned, $9 billion of Suharto's money was transferred from a Swiss bank to an Austrian bank.

Suharto's Residence (at 8 Jalan Cendana in Jakarta is a modest low-ceiling house, called Cendana, with a stuffed tiger in one room, family pictures on table and a glass cabinet filled with plates, trinkets and souvenirs. The garden is filled with caged myna birds that sing the Indonesian national anthem and say "Allah is great!" and is surround by a wall with doors that lead to the homes of his children. A frequent visitor to the house told the New York Times magazine, "The colors don't match, the sizes don't match—it’s like entering a curio shop. It's rather disconcerting to this very proper , dignified old man sitting there and look around the room and see all these nonsensical trinkets.”

Suharto and His Charitable Foundations

Charitable foundations set up by Suharto were conduits for money he acquired though corruption. The foundations helped build hospitals, schools and mosques, but they were also used as giant slush funds in which billions of dollars was laundered and divided out to business ventures involving his family and cronies. Much of Suharto shady financial dealings with in his foundation was legal at the time by a result of presidential decrees.

The foundation earned money from "voluntary donations" of 2.5 percent of the profits of state-owned banks and 2 percent of the income from people making over $40,000 a year. The foundations had huge stakes in Indonesian banks and was heavily invested in private companies.

Suharto used reforestation funds, earned from royalties in timber concession, to finance things like a $183 million airplane factory and a $102 million paper mill. Money that was to supposed to be in a fund for reforestation and fighting fires was diverted to the "national" car program. Investigations by the IMF found a "well endowed" reforestation fund but also found little of it had been spent reforestation. Most of it had used for cheap loans to plantation companies.

Natural disasters further exposed the regime’s decay. After a devastating tsunami struck Flores in 1992, killing thousands, much of the foreign aid intended for victims was siphoned off by corrupt officials.

Suharto's Family's Wealth and Corruption

Suharto's children lived near to Suharto in homes which had gardens that joined their father’s through doors between the dividing walls. Four of his six children—daughters Siti Hardiyanti Rukmana and Siti Hediati Harijadi and sons Bambang Trihatmodjo and Hutomo Mandala Putra — accumulated vast wealth and control over Indonesian businesses and industries. Suharto's eldest daughter Siti Hardiyanti Rukmana was sometimes mentioned as his possible successor. [Source: John Colmey and David Liebhold, Time May 24, 1999]

Suharto set up government-protected monopolies for his children, who also acted as middlemen in numerous government enterprises, taking 10 to 15 percent cuts but otherwise having little input in projects to build toll road, power stations and petrochemical plants. It was often said that easiest way to do business in Indonesia was to offer pieces of the action to a company controlled by one of Suharto's children. Under Suharto, Indonesia's 25 largest business were either run by Chinese tycoons with close ties to Suharto or Suharto's children. Suharto's wife wife, Siti Hartinah Suharto, known as Madame Tien, after the cut she took in projects she was involved in.

Marilyn Berger wrote in the New York Times: “While he occupied himself with affairs of state or relaxed with a round of golf or a day of fishing, his handled the family’s business affairs. She became the object of quiet criticism, with her detractors calling her “Madame Tien Percent,” a reference to what were said to be commissions she received on business deals. “But Madame Tien, who died in 1996, was restrained compared with the six Suharto children. They used their connections to amass as much as $35 billion from their business interests, according to an estimate by Transparency International, a private anticorruption organization. Cartels and monopolies extended the family’s reach to paper, cement, plywood, cloves, toll roads, power plants, automobiles and banks. “Whatever favors were not given to the Suharto family went to friends. A respected Indonesian scholar was quoted by The Times as saying: “At least 80 percent of major government projects go in some form to the president’s children or friends.” [Source: Marilyn Berger, New York Times, January 28, 2008]

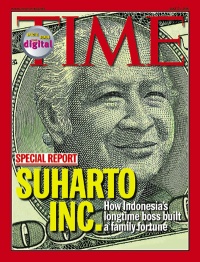

A Time article, titled "The Family Firm," alleged Suharto and his children amassed billions of dollars but that much of it was lost in the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis. The magazine alleged the family transferred some money from Switzerland to Austria and still had at least $15 billion in 1999. According to the article Suharto’s family became one of the richest in the world. At one time they reportedly had assets of $40 billion, half of Indonesia's gross national product, and about $73 billion passed through their hands between 1966 and 1999. Demonstrators at labor rallies sometimes display signs that read: "SUHARTO'S FAMILY OWNS EVERYTHING." One top industrialist told Newsweek, Suharto "sacrificed the nation's interests to those if his family.”

Assets and Monopolies Held by Suharto's Children

In 1992, Suharto's family had major stakes in at least 679 companies, including television and radio stations, chemical factories, drug companies, toll roads, shopping malls, hotels. shipping lines and taxi companies. Their holdings were so large they were often referred to as Suharto Inc. Suharto's children owned the planes that flew pilgrims to Mecca for the hajj and fought over the national auto company and other possessions. The Bank Central Asia was one third owned by Suharto's eldest son and daughter. The Suharto family also reportedly owned 3.6 million hectares of Indonesian land, an area equal to Belgium. This included many of the swankiest resorts in Bali, 100,000 square of prime real estate in downtown Jakarta and 40 percent of East Timor.

The Suharto children also had a number of overseas holdings, including homes in the United States and business ventures in Uzbekistan, the Netherlands, Nigeria and Vanuatu. The also owned a $4 million hunting ranch in New Zealand and a share in $4 million yacht moored in Darwin, Australia. Sudwikatmono, Suharto's half brother, had a monopoly on movie imports and theater chains. Suharto's youngest child and daughter, Sito Hutami Endang Adiningsih, known as "Mamiek" had an estimated worth of $30 million according to Time—a relatively modest amount compared to her other siblings. She had stakes in several of her siblings business ventures, owned a real estate company and received a favorable contract to clean up Jakarta Bay. She was reportedly was going to be paid $500 million for the job and then subcontracted the project to South Korea's Hyundai company for $100 million. The job was canceled in a crackdown on corruption.

Even Suharto's grandson, Ary Haryo Sigit, got a piece of the action: retail outlets, a share of water distribution company, an exclusive government license to sell fertilizer pellets and a monopoly on soup-making swallows nest. His plan to impose a tax on beer at resorts on Bali was scuttled after protests by brewers.

Suharto's Oldest Daughter and Son

Siti "Tutut" Hardijanti Rukmana is Suharto's oldest daughter and oldest child. She founded the Citra Lantoro Gung, a conglomerate with 90 companies with interests in toll roads, real estate, elevated trains, highways and power stations. She also owned a 16 percent stake Bank Central Asia, Indonesia's largest bank, and had a joint venture with Lucent Technologies. In 1999 Time estimated that her assets were worth $700 million. [Source: John Colmey and David Liebhold, Time May 24, 1999]

Tutu was also politically ambitious and served a Minister of Social Affair in her father's cabinet and at one time was regarded as Suharto's successor. The toll road to the airport reportedly earned her $40,000 a month while toll takers on the road earned $60 a month. At one time she owned a fleet of planes that included a Boeing 747, a DC-10, several 737s and BAC-111 that belonged to the Royal Squadron of Britain's Queen Elizabeth. She also owned a 12-room, $1 million house with a heated pool and tennis court near Boston and a house on London's Hyde Park worth much more. Known for her generosity, she flew her friends in her private jet or gave them first class tickets to Jakarta on commercial airliners.

Sigit, the oldest son, was a 16 percent shareholder in Bank Central Asia, a 10 percent owner of Mohammed "Bob" Hasan's Nusmaba Group, and a 40 percent owner of Tommy Suharto's Humpuss Group, and a partner in hundreds of other business ventures. He also ran an air freight company. In 1999, Time estimated his assets at $800 million.

Sigit also owned a $9 million home in an exclusive neighborhood in Los Angeles near his brother Bambang, two homes in the Hampstead area of London, worth $12 million each, and a home outside Geneva. He reportedly liked to spend his time playing video games and watching video tapes of Javanese shadow puppet plays while sitting on a Versace couch that no one else is allowed to sit on.

Sigit reportedly loved roulettes and baccarat and received the high roller treatment at casinos in London, Las Vegas, Atlantic City and Perth. A friend told Time he lost $3 million a night on several occasion and may have stacked up losses of $150 million during his gambling career. After one particularly bad losing streak, his father reportedly banned him from gambling abroad. Sigit then proceeded to lose $20 million in a call in cable television baccarat game.

Suharto's Second Oldest Son and Daughter

Suharto's second son Bambang Trihatmojdo became chairman of a conglomerate of some 90 companies with interests in everything from shipping and insurance to cocoa and timber, hotels, television, automobiles, even condoms. He was president and director and 38 percent owner of Bimantara Citra, one of Indonesia's largest conglomerates. It had 27 subsidiaries, over $1 billion in assets, holdings in telecommunications satellites, shipping, hotels, car production, natural gas and petrochemicals, banking and shopping malls. Bambang Trihatmojdo's also owned television stations, newspapers, radio outlets, and the company that owned the Grand Hyatt Jakarta hotel and the adjoining marble-draped shopping mall, the Plaza Indonesia, which boasted 170 stores including a Gucci and Bulgari. He also formed a joint venture with Hughes. Time estimated his worth in 1999 at $3 billion. [Source: John Colmey and David Liebhold, Time May 24, 1999]

Bambang Trihatmojdo had a $8 million penthouse in Singapore, a $12 million mansion in Los Angeles, two doors down from the house of Rod Stewert. One friend told Time he once cared about he poor but "I think he saw all the people around him getting rich and felt left out." In 1999, when a prohibition on his leaving the country was lifted, he moved with his family into a mansion in Bel Air, California, where he was occasionally spotted at the local bowling alley.

Suharto's second daughter Siti Hedijati Hariyadi, known as "Titiek," owned a finance company, real estate and telecommunications assets. She had an estimated worth of $75 million in 1999 and was married to Army Lt. Gen. Prabowo Subianto, who commanded the army's special forces and is from one of Indonesia's richest banking families. She formed a joint venture with General Electric and had a home on London's Grosvenor Square. She was reportedly very fond of large gemstones, hated dogs and was a heavy smoker. According to Time she slept in one room while her husband slept in another room with his German shepherds.

Suharto's Youngest Son "Tommy"

Suharto's youngest son Hutomo ("Tommy") Mandala Putra became the symbol of the excess of the Suharto era. Reportedly Suharto's favorite, he was a playboy and shady dealer convicted jailed on corruption and murder charges after Suharto was ousted. Tommy controlled a business empire worth hundreds of millions of dollars that included Indonesia’s leading private airline, Semapti Air, a monopoly on Indonesia's clove trade, and a 60 percent stake in the Humpus Group, a conglomerate with 60 subsidiaries. He also had holding in the automobile industry, shipping, oil and gas exploration and transportation. He forced villagers off their land in Bali so he could build a lavish resort there and also had a ranch in New Zealand, and a 75 percent stake in an 18-hole golf course and 22 luxury apartments in Ascot, England. In 1999, Time estimated his net worth at $800 million.

Tommy reportedly loved gambling and thought nothing of losing $1 million is a single night out. He often flew off to Europe's casinos in his private plane with large amounts of cash and deposited what he had left in Singapore on his way home. One business partner told Time, "Tommy loves money. And he always wanted it up front."

Tommy owned 70 percent of the Indonesian company that worked with South Korea's Kia Motors to produce Indonesia's controversial national car (See Automobile Industry). He was also a big fan of Formula One racing and claimed he was a race car driver (he once raced stocks cars with Marlboro as his sponsor). In the early 1990s, he had an international-class car race track built at a cost of $50 million Tommy formed a group that bought Lambroghini, the Italian sports car maker, for $40 million. He became a 60 percent shareholder in Lamborghini before Audi bought the company for around $100 million when Tommy was desperately in need of cash to bail out his other business concerns.

Tommy nearly singlehandedly killed the once lucrative glove industry by monopolizing it. In 1990, the clove industry was cornered by speculators, working with Tommy. A monopoly was created that brought a windfall of commissions and service fees to Tommy and his associates and more money for farmers at first. But as happens in a classic monopoly, farmers anxious to make more money produced more cloves, which in turn led to over production and a collapse of clove prices. Many farmers went bankrupt. They left their crops unharvested because the money they paid workers to pick them was more than money they could earn from the harvest. By 1996, things had gotten so out of hand that Tommy told clove farmer to burn half their crop to boost collapsed prices. The ploy didn't work and Tommy was eventually bailed out with government credits totalling $350 million.

Tommy served four years in prison for hiring a hitman to assassinate the judge who had convicted him of corruption. See Separate Article on Suharto’s Ouster.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025