SUKARNO

Nkrumah Sukarno (1901–70) was the leader of the independence movement, the father of modern Indonesia and Indonesia's first president. Known as "Bung Karno” (Brother Karno) as well as the Great Leader of the Revolution, Mouthpiece of the Indonesian People and Father of the Farmers, he founded the national ideology “pancasila” and was the driving force behind Indonesia for the first 17 years of its existence.

Unlike most earlier nationalist leaders, Sukarno had a talent for bringing together Javanese tradition (especially the lore of wayang theater with its depictions of the battle between good and evil), Islam, and his own version of Marxism to gain a huge mass following. An important theme was what he called "Marhaenism." Marhaen (meaning farmer in Sundanese) was the name given by Sukarno to a man he claimed to have met in 1930 while cycling through the countryside near Bandung. The mythical Marhaen was made to embody the predicament of the Indonesian masses: not proletarians in the Marxist sense, they suffered from poverty as the result of colonial exploitation and the islands' dependence on European and American markets. [Source: Library of Congress]

Sukarno aimed to make Javanese, Balinese, Acehese, Sumatrans and other groups to look beyond their own ethnicity as see themselves as Indonesians. Sukarno believed — -it seemed when nobody else did—that the far flung islands of the former Dutch empire could be unified into a nation. He was told it "is not going to work. They are totally different people, totally different cultures...We should have nothing to do with them." But in the end he achieved his goal with a minimum of bloodshed.

The late 1920s witnessed the rise of Sukarno to a position of prominence among political leaders. He became the country's first truly national figure and served as president from independence until his forced retirement from political life in 1966. Sukarno was a charismatic but he could also be an unpredictable demagogue who nearly bankrupted the country. In his autobiography he wrote, "He loves his country, he loves his people, he loves women, he loves art and, best of all, he loves himself." Even so Sukarno was adored by Indonesians. The Indonesia novelist Pramoedya Ananta Toer wrote in Time: "He united his country and set it free. He liberated his people from a sense of inferiority and made them feel proud to be Indonesian."

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUKARNO AS PRESIDENT: CHALLENGES, AUTHORITARIANISM, GUIDED DEMOCRACY factsanddetails.com

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNDER SUKARNO: NON-ALIGNMENT, ISOLATION, WAR WITH MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

DIFFICULTY MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK IN INDONESIA IN THE 1950s factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA DECLARES INDEPENDENCE IN 1945 AT THE END OF WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA’S NATIONAL REVOLUTION: THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE 1945-1949 factsanddetails.com

INDONESIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE (1945-1949): POLICE ACTION, ATROCITIES, MASSACRES factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA OFFICIALLY ACHIEVES INDEPENDENCE factsanddetails.com

RISE OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF THE DUTCH EAST INDIES (1942-1945) factsanddetails.com

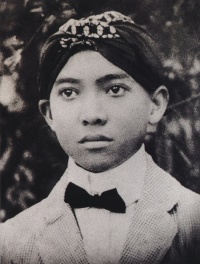

Sukarno's Early Life

The son of a Muslim lower priyayi (Javanese aristocrat) and and a middle-class Balinese woman, Sukarno was born in Blitar, a village near Surabaya, Java, about 650 kilometers (400 miles) east of Jakarta, on June 6, 1901. Sukarno's father, Raden Soekemi Sosrodihardjo was a primary schoolteacher from Grobogan, Central Java, and his mother, Ida Ayu Nyoman Rai, was from the Brahmin caste in Buleleng, Bali. Surkarno’s father moved to Surabaya following an application for a transfer to Java. [Source: Wikipedia]

Sukarno was originally named Kusno Sosrodihardjo. Following Javanese custom, he was renamed after surviving a childhood illness. Sukarno comes from the mythological hero Karna of the Mahabharata. The spelling Soekarno, based on Dutch orthography, is still in frequent use, mainly because Sukarno signed his name with the older spelling. Although Sukarno insisted on using a "u" rather than an "oe," he said that he had been taught in school to use the Dutch style. After 50 years, he said, it was too difficult to change his signature, so he continued to use the "oe." Official Indonesian presidential decrees from 1947 to 1968, however, used the 1947 spelling. Soekarno–Hatta International Airport, which serves the area near Indonesia's capital, Jakarta, still uses the Dutch spelling.

Sukarno was good in sports and academics and was one of the few Indonesians to be let into a Dutch-language school. While at a Dutch-language secondary school in Surabaya met and boarded with the country's most well known nationalists,Cokroaminoto (Tjokroamino), who introduced the young Sukarno to separatist politics.

Sukarno's Education

Sukarno was educated in East Java and Europe before studying at the new Technical College Bandung Institute of Technology), one of the best and most expensive schools in the colony, where associated with leaders of the Indies Party and Sarekat Islam in his youth and was especially close to Cokroaminoto until his divorce from Cokroaminoto's daughter in 1922. A graduate of the technical college at Bandung in July 1927, he, along with members of the General Study Club (Algemene Studieclub) established the Indonesian Nationalist Union (PNI) the following year. Known after May 1928 as the Indonesian Nationalist Party (PNI), the party stressed mass organization, noncooperation with the colonial authorities, and the ultimate goal of independence. [Source: Library of Congress]

Sukarno studied civil engineering with a focus on architecture. He was "intensely modern" in both architecture and politics. He despised traditional Javanese feudalism, considering it "backward" and blaming it for the country's fall under Dutch occupation and exploitation. He also despised the imperialism practiced by Western countries, calling it "the exploitation of humans by other humans" (exploitation de l'homme par l'homme). He blamed this for the deep poverty and low levels of education of the Indonesian people under the Dutch. [Source: Wikipedia]

After graduating in 1926, Sukarno and his friend from university, Anwari, established the architectural firm Soekarno & Anwari in Bandung. The firm provided planning and contracting services. Among Sukarno's architectural works are the renovated Preanger Hotel building (1929), for which he acted as assistant to the renowned Dutch architect Charles Prosper Wolff Schoemaker. He also designed many private residences on Jalan Gatot Subroto, Jalan Palasari, and Jalan Dewi Sartika in Bandung.

Sukarno's Character and Charisma

It has been said that Sukarno was found of mistresses, uniforms and bombast. He lived in a grand presidential palace and may have had as many as nine wives. His second wife was a Balinese Hindu. His glamorous third wife, Dewi, was a former Japanese hostess at Tokyo's Copabacana nightclub and is now a big celebrity in Japan. He named his son after the Indonesian words for "Lighting," "Thunder," and "Typhoon."

Even among the country's small educated elite, Sukarno was atypical in that he was fluent in several languages. In addition to Javanese, the language he grew up with, he was a master of Sundanese, Balinese, and Indonesian. He was especially strong in Dutch. He was also quite comfortable with German, English, French, Arabic, and Japanese, all of which were taught at his high school. His photographic memory and precocious mind helped him. [Source: Wikipedia]

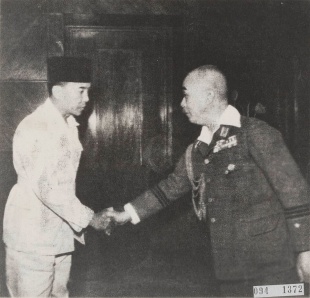

Sukarno was a dashing impulsive soldier who liked to flash a winning smile behind dark sunglasses. The Indonesian called him “bung” (older brother) and felt he was one of them as well as a charismatic leader. He practiced both Islam and Javanese mysticism. Sukarno once called himself a "God-King." He and Suharto both reportedly believed in “wahyu”, the Javanese belief that some people have a divine mandate to rule. Sukarno was also inspired by the ideals of the French Revolution and the Enlightenment.

Sukarno counted John F. Kennedy among his friends. He was inspired by the proto-fascist Italian poet Gabriele D’Annunzio who in turn was a devotee of Nietzche. The term “live dangerously” was first used b D’Annunzio. Sukarno used the term the “year of living dangerously” to exhort Indonesians to prepare for hard times ahead.

Sukarno had a mellifluous voice and a fondness for “loopy, inventive acronyms.” He had the power to arouse people with his oratory. He "garnered support from the poor by whipping up nationalism and colorful rhetoric and brash diplomatic loves. His rallying cry was, “Freedom! Freedom! Freedom!”

Sukarno held crowds spellbound with his speeches and fired them up with his rhetoric. Recalling when he was a student, a political science professor told the Washington Post, "I had goose pimples whenever I heard President Sukarno make speeches. But after the speeches, we went back to the grueling life of standing in line for soap, for rice, for basic necessities." Life was hard "but we felt like we were traveling on top of the world. There was a great sense of unity."

Sukarno’s Sex Life

Sukarno’s personal life drew criticism; he married at least six times and was notorious for extramarital affairs and was the target of a KGB honey trap. While studying in Bandung, Sukarno became romantically involved with Inggit Garnasih, the wife of Sanoesi, the owner of the boarding house where Sukarno lived. Inggit was 13 years older than Sukarno. In March 1923, Sukarno divorced Siti Oetari to marry Inggit, who had also divorced Sanoesi. Sukarno later divorced Inggit and married Fatmawati.

According to Pravda: Sukarno “was known for his sexual passion. That is why KGB sent a group of young girls to him during his visit to Moscow. Those girls got acquainted with Ahmed Sukarno in a plane, under the disguise of air hostesses, then he invited them to his hotel room in Moscow and arranged a grand orgy. The orgy was filmed by two candid cameras that were fixed behind mirrors. It seemed that the operation was just perfect. [Source: Pravda.Ru, July 8, 2002]

Before starting the blackmail, KGB invited Sukarno in a small private movie theatre and showed him the pornographic video, in which he was playing the main part. KGB agents were expecting him to get really frightened, that he would agree to cooperate with them at once, but everything happened vice versa: Sukarno fondly decided that it was a gift from the Soviet government, so he asked for more copies to take them back to Indonesia and show them in movie theatres. Sukarno said to flabbergasted agents that the people of Indonesia would be very proud of him, if they could see him doing the nasty with Russian girls.

Sukarno's Early Political Activity

While at Bandung Institute of Technology, regarded in his time as a focal point for political activity, radical Islam and Communism. He founded the Bandung Study Club on the model begun in Surabaya by the early Budi Utomo leader Dr. Sutomo (1888–1938), an ophthalmologist.

In 1927, Sukarno helped found the Partai National Indonesia (PNI), the Indonesian Nationalist Party, a pro-independence organization that blended Javanese, Western and socialist philosophies. Sukarno declared, “Give me 10 youths who are fired with zeal and with love for our native land, and with them I shall shake the earth.” It became the most significant nationalist organisation and was the first secular party devoted primarily to independence but the movement remained politically weak until World War II.

The fundamental idea that Sukarno invested in the PNI was that achieving the nation—acquiring independence from Dutch rule—came before and above everything else, which meant in turn that unity was necessary. Quarrels about the role of Islam or Marxist ideas or even democracy in an eventual Indonesia were at the moment beside the point. Social class was beside the point. All differences dissolved before the need for unity in reaching the goal of “merdeka”.

The Minangkabau Sutan Syahrir (1909-66) and Mohammad Hatta became Sukarno's most important political rivals. Graduates of Dutch universities, they were social democrats in outlook and more rational in their political style than Sukarno, whom they criticized for his romanticism and preoccupation with rousing the masses. In December 1931 they established a group officially called Indonesian National Education (PNI-Baru) but often taken to mean New PNI. The use of the term "education" reflected Hatta's gradualist, cadre-driven education process to expand political consciousness. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Sukarno was arrested by the Dutch colonial government in 1929 and placed on trial for sedition in 1930, where he defended himself with an eloquent castigation of colonialism that lasted for two days and became known as Indonesia Menggoegat (“Indonesia Accuses!”). Sukarno served two years in prison. When he was released in 1931 he was regarded as hero by ordinary Indonesians. Taken into custody again in 1933, he was held under house arrest, first in remote Ende, Flores, then in Bengkulu, western Sumatra, until the Japanese occupation. While Sukarno was exiled on Flores, home of large number of Christians, he wrote movingly about the common values of Catholics and Muslims. The PNI for all intents and purposes was banned. Sukarno was freed from confinement when the Japanese arrived in 1942 during World War II.

Sukarno collaborated with the occupying Japanese during World War II. The Japanese allowed him to establish a nationalist umbrella group. In Jakarta he helped recruit Indonesian laborers for the Japanese war effort, many of who died working under slave-like conditions in Malaysia and Burma. Later admitted, “I shipped them to their deaths. Yes, yes, yes, I am the one.” But at the same time Sukarno used Japanese “singing trees” (loudspeakers) to get his nationalist message out to the masses. After the defeat of the Japanese he declared independence from colonial rule.

Sukarno Ideology

Beyond the goal of independence, Sukarno envisioned a future Indonesian society freed from dependence on foreign capital: a community of classless but happy Marhaens, rather than greedy (Western-style) individualists, that would reflect the idealized values of the traditional village, the notion of gotong-royong or mutual self-help. Marhaenism, despite its convenient vagueness, was developed enough that by 1933 nine theses on Marhaenism were developed in which the concept was synonymous with socio-nationalism and the struggle for independence. Mutual self-help in diverse contexts became a centerpiece of Sukarno's ideology after independence and was not abandoned by his successor, Suharto, when the latter established his New Order regime in 1966. Considering himself a Muslim of modernist persuasion, like Ataturk in Turkey, Sukarno advocated the establishment of a secular rather than Islamic state. This understandably diminished his appeal among Islamic conservatives in Java and elsewhere. [Source: Library of Congress *]

In 1921 Sukarno had fashioned the idea of “marhaen”, the “ordinary person” representing all Indonesians, as a substitute for the Marxist concept of proletariat, which he found too divisive, and argued that developing a mass following among ordinary folk was the key to defeating colonial rule. And in 1926 he published a long essay entitled “Nationalism, Islam, and Marxism,” in which he laid the foundation for a new nationalism, one that was neither Muslim nor Marxist but comprised its own—national—ideology, largely by suggesting that significant differences could not exist among those who were serious about struggling for freedom. This extravagant inclusiveness did not, however, extend to race. Sukarno pitched the struggle as between us (Indonesians) and others, “sini “or “sana “(literally, here or there), a “brown front” against a “white front.” With respect to the colonial state, one was either “ko “or non-“ko “(cooperative or not). Sukarno specified in the PNI statutes that non-Indonesians— Eurasians, Chinese, whites—could aspire only to associate membership at best. In his 1930 defense oration when on trial by the colonial authorities, entitled “Indonesia Menggugat!” (Indonesia Accuses!), Sukarno also depicted the Indonesian nation as not merely an invention of the present but rather a reality of the historical past now being revived. It was a glorious (racial) past leading through a dark present to a bright and shining future. *

These ideas, delivered in Sukarno’s famously charismatic style, were both radical and seductive. Part of their attraction was that they stirred deep emotions; in part, too, they permitted, even encouraged, the denial of genuine differences among Indonesians, and the highlighting of those between Indonesians and others. Not everyone agreed with the PNI program, even among those who joined. Mohammad Hatta and Sutan Syahrir, Sumatrans who were among Sukarno’s closest associates and later served him as vice president and prime minister, respectively, both had misgivings about the “mass action” approach and warned as early as 1929 against demagoguery and the growth of an intellectually shallow nationalism. Syahrir also was scathing about the “sini “or “sana “concept, especially for the way it implied an unbridgeable gap between East and West, a concept Syahrir thought both mythical and dangerous. Hatta was perhaps more equivocal, for in the Netherlands in 1926, as president of the Perhimpunan Indonesia (Indonesian Association), which had succeeded the Indonesische Vereniging, he had specifically prohibited Eurasians from membership.

The encompassing, driving sense of national unity and the defiant stand against colonial rule were, nevertheless, widely appealing and influenced Indonesians everywhere. They were clearly an inspiration behind the decisions of the Second Youth Congress in 1928, which adopted the red-and-white flag and the anthem “Indonesia Raya” (Great Indonesia) as official national icons, and on October 28, 1928, passed the resolution known as the Youth Pledge (Sumpah Pemuda), which proclaimed loyalty to “one birthplace/fatherland “(bertumpah darah satu, tanah air”): Indonesia; one people/nation (“satu bangsa”): Indonesia; and one unifying language “(bahasa persatuan”): Indonesian.” Little matter that, for example, the Malay language on which this new “Indonesian” was to be based was at the time little spoken among the Dutch-educated students who proclaimed it the national language; they would learn and develop it as they developed the nation itself.

Sukarno During the Japanese Occupation

Both Sukarno and Hatta agreed to cooperate with the Japanese in the belief that Tokyo was serious about leading Indonesia toward independence; they were, in any case, convinced that outright refusal was too dangerous. (Syahrir declined to play a public role.) Their cooperation was a dangerous game, which later earned both leaders criticism, especially from the Dutch and the Indonesian political left, for having been “collaborators.”

Sukarno’s role in recruiting “rōmusha “became a particularly sore issue, although he later stubbornly defended his actions as necessary to the national struggle. Some Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama leaders followed Sukarno’s cooperative lead, seeing no reason why, if the Japanese were trying to use them to mobilize Muslim support, they should not use the Japanese to advance Muslims’ agenda. They saw some advantage in the formation of the Consultative Council of Indonesian Muslims (Masyumi), which brought modernist and traditionalist Muslim leaders together, and of its military wing, the Barisan Hisbullah (Army of God), intended as a kind of Muslim version of Peta. But on the whole, Muslim enthusiasm for cooperation with the Japanese did not match Sukarno’s. [Source: Library of Congress]

Sukarno's Last Years

By the early 1960s, Sukarno’s health had declined and many in Jakarta sensed that he was losing control. When Mount Agung erupted in Bali in 1963, some interpreted it symbolically as a sign of his waning authority. By 1965, Sukarno's government was riddled with corruption, indecision and economic decline. After Suharto took over in October 1965, Sukarno stayed on as President and insisted that he was in charge of the country although it was Suharto that really was. In February 1967, five four-star generals—the heads of army, navy, air force and national police, plus the minister of defence—showed up at Medeka Palace, the official residence of the president. They had been sent by Suharto to persuade Sukarno to officially transfer power to Suharto.

By that time Sukarno had lost nearly all of his official powers. He had been censured by the legislature but he still had millions of loyal supporters. Emotions ran high at the Japanese 1967 meeting. Sukarno repeatedly said, “How could you do this to me” to which the others responded with tears. In the end Sukarno agreed to leave, reportedly to spare Indonesia civil war. Suharto became the head of the Indonesian government and Sukarno lived the last years of his life under house arrest in Bogor Palace.

Sukarno died in 1970. On his deathbed he told his daughter Megawati, "Don't speak of my suffering and illness to the people. Let me be sacrificed, if unity in Indonesia is achieved. Let my suffering become a witness that even the power of the President has its limitations. Lasting power must be led by the people, and only God Almighty is omnipotent."

Sukarno was buried in his hometown of Biltar under a simple grave site with the inscription: "I hand over the nation and the country to you." In 1978, the simple grave was replaced by an orate monument with the same inscription on Suharto's orders. It is visited by thousands every year.

RELATED ARTICLES:

COUP OF 1965 AND THE FALL OF SUKARNO AND RISE OF SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: KILLERS, VICTIMS, REASONS factsanddetails.com

LEGACY OF THE VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: FEAR, FILMS AND LACK OF INVESTIGATION factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO: HIS LIFE, PERSONALITY AND RISE TO POWER factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025