SUHARTO

General Suharto (1921–2008) was one of the longest ruler dictators of the 20th century. He ruled Indonesia for 32 years. After Zaire's Mobutu fell in 1997, only Fidel Castro was a dictator longer. When Suharto retired in 1998, he was the only president 65 percent of the population of Indonesia had ever known. Suharto was a stanch anti-Communist, a leader in Third World movement and a brutal authoritarian. He was one of the few dictators bold enough to place his portrait on his country’s currency while he was in office. Many ordinary Indonesians believed he was a reincarnation of a Javanese king with a mandate from heaven to govern.

After the upheaval, chaos and uncertainty that characterized the Sukarno years many people were happy with the stability and security that Suharto brought even it meant the loss of democracy and freedom. Suharto eliminated the Communist threat and successfully promoted a national identity and reduced regional, religious and ethnic divisions. But also tens of thousands — likely hundreds of thousands—were killed under his watch.

Kerry Brown wrote in the Asian Review of Books, “Suharto was, seen outside his cultural and historical context, something of an enigma. His early career as a soldier was undistinguished, and he almost chanced upon power in 1965 when he survived the purge of the Generals alleged to have been planning a Communist coup by the Sukarno government. This left the way for Suharto to make his gamble for power when it came, in 1966—unleashing a huge purge of Communists, something Parry comments, which involved the enthusiastic involvement of thousands of ‘normal people’ (rather than the army or security services) who managed to slaughter between half a million to a million purported ‘communist’ activists. Suharto’s ensuing 33 years of rule were characterised by a depoliticisation of society, and a blandness which was almost miraculous in view of the country’s massive complexity and the potential for conflict. This paradoxical blandness was personified in Suharto, a man who lived in relative simplicity (his house in Jakarta apparently largely furnished with kitsch) and who travelled rarely, never raised his voice in public, and yet who instilled fear in his subordinates, and dealt with any opposition for three decades with ruthless efficiency. [Source: Kerry Brown, Asian Review of Books, May 4, 2005]

RELATED ARTICLES:

COUP OF 1965 AND THE FALL OF SUKARNO AND RISE OF SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: KILLERS, VICTIMS, REASONS factsanddetails.com

LEGACY OF THE VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: FEAR, FILMS AND LACK OF INVESTIGATION factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER SUHARTO: NEW ORDER, DEVELOPMENT, FOREIGN POLICY factsanddetails.com

REPRESSION UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

CORRUPTION AND FAMILY WEALTH UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

1997-98 ASIAN FINANCIAL CRISIS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998: PRESSURES, EVENTS, RESIGNATION factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO AFTER HIS RESIGNATION: TRIALS, DEATH, LEGACY, VIEWS, FAMILY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO AS PRESIDENT: CHALLENGES, AUTHORITARIANISM, GUIDED DEMOCRACY factsanddetails.com

Suharto's Early Life

The son a poorly educated peasant farmer, Suharto was born on June 8, 1921 in a bamboo hut in Kemusuk, a part of the larger village of Godean,, in central Java west of Yogyakarta, the former royal capital in central Java. He was the only child from his father’s second marriage, but he had 11 half-brothers and sisters. His father was a village irrigation official in charge of distributing water to rice growers. [Source: Marilyn Berger, New York Times, January 28, 2008]

Suharto's parents were separated when Suharto was young. He lived with several different families including his mother’s home, his aunt’s, his father’s and his stepfather’s.. When he was 14 he moved into the home of a notable “dukan” (traditional Javanese mystical healer) named Daryatmo, who became the first guru in his life and remained an adviser to Suharto in his later years. Mysticism was important to Suharto throughout his life.

Suharto received little formal schooling and his education stopped in 1939 at junior high school. . It has been said he was so poor that he once had to change schools because he could not afford the shorts and shoes that were the required uniform. John Gittings wrote in The Guardian, “It had been a long journey from his birthplace. His father was a minor official under Dutch rule, supervising water distribution to the fields, in return for which he was allocated two acres to farm. His mother had distant aristocratic origins, being descended from one of the sultan of Jogjakarta's concubines some generations back. Suharto himself seems to have been rather unhappy, and frequently changed his name through life — a Javanese device to fend off evil spirits at a time of personal failure. He worked briefly in a village bank, and would later claim he lost the job because his only sarong was accidentally torn and he could not afford to replace it. The alternative version is that he was sacked for stealing clothes, and was ordered by the court to join the army as an alternative to prison. "[Source: John Gittings, The Guardian, January 27, 2008 +++]

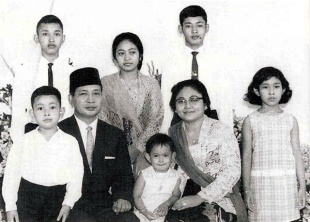

In 1947 he married Siti Hartinah; they had six children, Siti Hardiyanti Hastuti Rukmana, Sigit Harjojudanto, Bambang Trihatmodjo, Siti Hediati, Hutomo Mandala Putra and Siti Hutami Endang Adiningsih, who survive, along with 11 grandchildren and a great-grandchild.

Suharto's Early Military Career

Suharto joined the Dutch army just before the start of Worlf Wae II and over of the course of nine years served with the Dutch, the Japanese, the anti-Dutch liberation army and the fledgling Indonesian army. During World War II, Suharto used the invasion of Indonesia by Japan as a means of fighting against colonialism. He received military training in Peta and became a battalion leader in Japan's 'self-defense corps." His half brother told Time, "He came riding into the village on a horse—it was rare to see someone on a horse in our village."

After the Japanese surrender he joined the independence forces, emerging as a lieutenant colonel, steeped in anticolonialism and anti-Communism. During the war for independence, he distinguished himself by leading a lightning attack on Yogyakarta, seizing it on March 1, 1949, after the Dutch had captured it in their second "police action." He used that position to secure a position as a career army officer when Indonesia became independent. A former soldier who served in a battalion with Suharto told Time, "He was a very a noble figure. Everyone revered him. He had a good reputation at the front. He didn't talk much. He was distant from us. He was someone you had to be afraid of. And don't forget—he was educated by the Japanese army. He has the ethics of the samurai. They never surrender." Rising quickly through the ranks, Suharto was placed in charge of the Diponegoro Division in 1962 and Kostrad the following year.

After attending the army staff and command school, he was made a brigadier general and placed in charge of intelligence. He rose to command the army’s new Strategic Reserve Force, the position he held when the six generals were killed in 1965. John Gittings wrote in The Guardian, “The only path forward for young men in what was then the Dutch East Indies - outside the tiny elite sent to college - was the army. Suharto joined the Royal Netherlands Indies army in 1940, and soon became a sergeant. When the Japanese invaded in 1942, the Dutch commander in chief, Lieutenant General Ter Poorten, surrendered precipitately. Any respect for the colonial power was lost. Suharto, with tens of thousands of others from the disbanded force, joined Peta, the Volunteer Army of Defenders of the Motherland, whose explicit aim was to help Japan defend Indonesia against invasion by the western allies. In fact, nationalist leaders such as Sukarno and Mohammed Hatta used support for Japan to arouse a more general sense of anti-imperialism. [Source: John Gittings, The Guardian, January 27, 2008 +++]

“The Japanese turned ex-NCOs, including Suharto, into officers and gave them further military education, including lessons in the use of the samurai sword. Suharto's adulatory biographer, OG Roeder, records in “The Smiling General” (1969) that his subject was "well known for his tough, but not brutal, methods". When, in August 1945, the Japanese surrender brought the second world war to a close, its forces were ordered by the allies to prevent an Indonesian nationalist takeover. However, Peta units refused to disarm, seizing control of several large towns. Suharto led a raid on the Japanese garrison at Jogjakarta. In the official account, he is also credited with foiling a communist coup against Sukarno. In a more plausible interpretation, he supported the conspiracy when it appeared likely to succeed, but betrayed it once it had failed. Fact and myth are equally hard to disentangle in his career. +++

Suharto's Character

Suharto had a gentle, calm demeanor and some called him the "smiling general." He read speeches in a flat, even tone and never displayed any emotion. In his autobiography, he claimed he lived according to "the three don't": “Aja kagetan” ("don't be startled"), “aja gumunan” ("don't be overwhelmed") and “aja dumeh” ("don't feel superior"). Suharto liked golf, deep-sea fishing and driving around the grounds of his home in a Harley Davidson and a side car with his vice president B.J. Habibie in the sidecar. He was once photographed with arm around a stewardess.

Marilyn Berger wrote in the New York Times: Suharto was an unlikely character to play such a major role in his country’s destiny. He was a private person, and although he wielded complete power, he spoke in gentle tones, smiled sweetly to friend and foe and presented himself as a man of humble origins, shy, retiring and enigmatic. Short and thick set, he almost invariably dressed in a Western business suit or a safari jacket once he gave up his military uniform, and a black songkok, the flat traditional Indonesian cap. [Source: Marilyn Berger, New York Times, January 28, 2008]

“He rarely took a public stand on any issue. Instead, by waiting to allow a consensus to form, he was usually able to make events evolve the way he wished. He can be better understood in the context of the old forms of Javanese kingship in which the ruler was surrounded by courtiers who tried to divine the royal mind.

Suharto had a thick Javanese accent. He frequently used malapropisms, which were copied by his aides. During some interviews Suharto fielded questions in English and answered them in Bahasa Indonesian. Suharto's half brother Notosuwito told Time, "He is never emotional...Suharto is quiet, searching for a way. If he has already worked it out, he speaks and everyone is surprised. He himself is never surprised, but he surprises other people." Notosuwito also told Time, "Suharto was conditioned by his village...He has an obligation to the people below him. It is certain he feels sad...but he never shows his sadness to the people. He has a fighting spirit, and he will struggle until he dies for the welfare of the people."

Suharto and Superstition

Suharto considered himself a devout Muslim but was very superstitious. He regularly consulted traditional Javanese mystics, sorcerers and astrologers. He often consulted a “dukan” before making important decisions and reportedly believed that events were sometimes driven by forces manifested through a relationship between retail bar codes and the number 666. Suharto liked to visit a sacred cave on Java's Dieng plateau, the spiritual home of Semar, the infamous Javanese buffoon-god, and meditate there.

Marilyn Berger wrote in the New York Times: “Suharto seemed imbued with Indonesian traditions of animism and mysticism overlaid with Hindu and Buddhist teachings. In a country given to superstition, where ancient patterns of belief coexist with more modern ideas, he consulted gurus and dukuns, spiritual advisers and soothsayers who were believed to be in touch with natural forces. [Source: Marilyn Berger, New York Times, January 28, 2008]

Suharto regularly consulted astrologers and made policy on their recommendations. Describing one of Suharto's dukun in action, Dorinda Elliot wrote in Time, "Working himself into a trance, Kusandi tenses, pating, growling, lunging with knuckles flexed. With spirits help, he says, he has 'become a tiger.'" Suharto tried to develop his own mystical powers. When one of his spiritual advisors was asked by National Geographic how Suharto could be forced from power if he had mystical powers, the advisor said, “He didn’t listen to me.”

Suharto During the Sukarno Years

After Sukarno declared Indonesian independence in 1945, Suharto joined Sukarno's revolutionaries and emerged as an officer when Indonesia was recognized as an independent country in 1949. During most of the Sukarno years, Suharto was an uncharismatic but steady mid-ranking officer. He "used an innate shrewdness and an ability to play rivals off one another," was involved in crushing a popular uprising in the 1950s in the islands, and befriended influential Chinese businessmen.

In the 1950s, Suharto was reportedly involved in a sugar smuggling operation and given a less prestigious command as punishment after he was caught. Even so Suharto rose through ranks to become an influential general and head of the Strategic Reserve Command in Jakarta, which protected the capital.

John Gittings wrote in The Guardian, “When Indonesia gained independence in 1949 after a four-year struggle against the Dutch, Sukarno became the country's first president. Suharto, by then a colonel in the new national army, took part in the pacification of rebellious forces in South Sulawesi, where his troops earned a reputation for extreme brutality. Suharto and his colleagues saw themselves as operators — and the army as the mechanism — to steer Indonesian society through a transition beset by militant communism and Islam. Less visible than the senior generals around Sukarno, they were waiting in the wings for the president's uneasy coalition of Muslims, the PKI and the army to crumble.” [Source: John Gittings, The Guardian, January 27, 2008 +++]

Suharto and the Coup and Counter Coup of 1965

On September 30 and the wee hours of October 1, 1965, whule Sukarno was President of Indonesia, a faction of young officers in Jakarta, launched a so called coup by kidnapping and assassinating six top generals, including Army Chief of Staf Yan. Their bodies were dumped in a well near Jakarta’s air force base. The effort was ill-conceived and poorly executed and had little support from within the army let alone the nation as a whole. The group behind the coup claimed they had acted as they did to foil a plot organized by the generals to overthrow the president.

Suharto may have known of the plot in advance. After the September 1965 attempted coup Suharto orchestrated a counter-coup and an anti-communist purge that embraced the whole of Indonesia. Hundreds of thousands of communists and their sympathisers were slaughtered or imprisoned, primarily in Java and Bali. The party and its affiliates were banned and its leaders were killed, imprisoned or went into hiding. [Source: Lonely Planet]

On October 1 1965, faced with the news of this apparent coup attempt, Suharto, the commander of the Army Strategic Reserve Command (Kostrad), who had not been on the list of those to be captured, moved swiftly, and, less than 24 hours after events began, a radio broadcast announced that Suharto had taken temporary leadership of ABRI, controlled central Jakarta, and would crush what he described as a counterrevolutionary movement that had kidnapped six generals of the republic. (Their bodies were not discovered until October 3.) When the communist daily Harian Rakjat published an editorial supportive of the Revolutionary Council on October 2, 1965, it was already too late. In Jakarta, the coup attempt had been broken, and anti-PKI, anti-Sukarno commanders of ABRI were in charge. Within a few days, the same was true of the few areas outside of the capital where Gestapu had raised its head.

On the night of the coup Suharto was visiting his youngest child in a hospital, and it was said that that was how he escaped assassination. According to the New York Times: He blamed the Indonesian Communist Party for what he described as an abortive coup , though the Communists’ exact role in it remains unclear, and and questions have lingered about why Mr. Suharto was one of the few senior officers not marked for assassination. In any event, he became the chief beneficiary of the subsequent crackdown as he moved quickly to consolidate his control. [Source: Marilyn Berger, New York Times, January 28, 2008]

Suharto Gains Control After the 1965 Coup

The period from October 1965 to March 1966 witnessed the eclipse of Sukarno and the rise of Suharto to a position of supreme power. After the elimination of the PKI and purge of the armed forces of pro-Sukarno elements, the president was left in an isolated, defenseless position. By signing the executive order of March 11, 1966, Supersemar, he was obliged to transfer supreme authority to Suharto. On March 12, 1967, the MPRS stripped Sukarno of all political power and installed Suharto as acting president. Sukarno was kept under virtual house arrest, a lonely and tragic figure, until his death in June 1970. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Suharto gradually consolidated authority while keeping President Sukarno as a symbolic figurehead. Throughout the period from 1965 to 1966, Sukarno vainly attempted to restore his political stature and return the country to its position prior to October 1965. Using the 1965 “coup” as an excuse to clean house Suharto consolidated his power and either struck deals or eliminated potential rivals. After aligning himself with conservatives, Suharto removed "undesirable" elements from his organization, banned the Communist PKI, appointed loyalista to key positions in the cabinet, and lead the Indonesian military in a brutal crackdown on Communists in Indonesia. He received secret support from the U.S. as part its drive against communism.

By mid-October 1965, two weeks after the coup, the army, under the command of Suharto, was in virtual control of the country and as leader of the armed forces he set about maneuvering Sukarno from power and eliminating rivals. On March 12, 1966, following nearly three weeks of student riots, and while after troops loyal to Suharto surrounded the Presidential Palace, President Sukarno transferred to Suharto the authority to take, in the president's name, "all measures required for the safekeeping and stability of the government administration." In this way Suharto established himself as the Army Chief of Staff and assumed effective power of the Indonesian government (Sukarno was politically crippled and Suharto had the support of the military). Pramoedya Ananta Toer wrote, Suharto "tried to legitimize his rule by claiming Sukarno had conferred power to him in a letter dated March 11, 1966—a letter which has never been produced to the public and is now said to have been 'lost'."

In mid-1966, the Provisional People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR(S)) demanded that Sukarno account for his behavior regarding Gestapu, but he stubbornly refused; only early the next year did he directly claim that he had known nothing in advance of those events. But by then, even many of his supporters had lost patience.

On March 12, 1967, the the Provisional People's Consultative Assembly (MPRS) formally removed Sukarno from power and appointed Suharto acting president in his stead. One year later, it conferred full presidential powers on Suharto, and he was sworn in as president for a five-year term. The congress also agreed to postpone the general elections due in 1968 until 1971. The New Order thus officially began as the Old Order withered away.

Suharto After Taking Power

After taking power in March 1966, Suharto officially banned the Indonesia Communist Party (PKI) and its surviving leaders, as well as prominent pro-Sukarno figures, arrested and imprisoned. Over the next few months, the new government largely dismantled Sukarno’s foreign policy as Jakarta broke its ties with Beijing, abandoned confrontation with Malaysia, rejoined the UN and other international bodies, and made overtures to the West, especially for economic assistance. The Inter-Governmental Group on Indonesia (IGGI) was formed to coordinate this aid. Indonesia also became a founding member of ASEAN in 1967.

According to Lonely Planet: Pro-Sukarno soldiers and a number of cabinet ministers were arrested. A new six-man inner cabinet, which included Suharto and two of his nominees, Adam Malik and Sultan Hamengkubuwono of Yogyakarta, was formed. Suharto then launched a campaign of intimidation to blunt any grass-roots opposition. Thousands of public servants were dismissed as PKI sympathisers, putting thousands more in fear of losing their jobs. By 1967 Suharto was firmly enough entrenched to finally cut Sukarno adrift. The People’s Consultative Congress, following the arrest of many of its members and an infusion of Suharto appointees, relieved Sukarno of all power and, on 27 March 1968, it ‘elected’ Suharto as president. [Source: Lonely Planet]

On July 3, 1971, national and regional elections were held for the majority of seats in all legislative bodies. The Joint Secretariat of Functional Groups (Sekber Golongan Karya—Golkar), a mass political front backed by Suharto, gained 60 percent of the popular vote and emerged in control of both the House of Representatives (DPR) and the MPR. Pramoedya wrote, the general election was held in accordance Suharto’s “taste and needs. Two years later he required all political currents to merge into just three parties, yielding a 'constitutional state' complete with recognition and support of Western countries."

Suharto and the Violent Crackdown on Communists in 1965-66

In the violent aftermath of the failed coup of 1965, thousands of suspected Communists were executed, and widespread vigilante killings erupted between October and December of that year. Estimates of the death toll range from 500,000 to 1 million. Many ethnic Chinese were targeted, and in parts of East and Central Java and in Bali entire villages were destroyed. In 2012, Indonesia’s National Commission on Human Rights classified the events as a gross violation of human rights. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

John Gittings wrote in The Guardian, After the October 1965 coup Suharto quickly suppressed the uprising. Over the next six months, army units and local vigilante groups launched a nationwide purge of so-called communists, a catch-all label that included labour and civic leaders and thousands of others who would never have even heard of Karl Marx. Most were shot, stabbed, beaten to death or thrown down wells in acts of horrifying violence. [Source: John Gittings, The Guardian, January 27, 2008]

Marilyn Berger wrote in the New York Times: Suharto's precise role in the violence is not clear; he managed to keep his name from being directly attached to it. What is clear is that in many areas the army, which he controlled, supplied weapons to and whipped up a tense population to mutilate and murder people suspected of being Communists, many of them of Chinese ancestry. [Source: Marilyn Berger, New York Times, January 28, 2008]

“Contemporary dispatches reported that the general sent crack troops of the army’s Strategic Reserve Command to organize the liquidation of the Communists. Hamish McDonald, a journalist with wide experience in Asia, wrote in his book “Suharto’s Indonesia” that General Suharto later dispatched Col. Sarwo Edhi Wibowo with a force of commandos “to encourage the anti-Communist civilians to help with the job.” The colonel said, “We gave them two or three days’ training, then sent them out to kill the Communists.” Along with presumed Communists, entire families were wiped out and personal scores settled with ethnic Chinese, longtime residents of the country.

See Separate Articles: VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: KILLERS, VICTIMS, REASONS factsanddetails.com LEGACY OF THE VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: FEAR, FILMS AND LACK OF INVESTIGATION factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025