INDONESIA WHEN SUHARTO TOOK OVER

When Suharto took over Indonesia, the country was bankrupt. and desperately in need of some stability. The archipelago had experienced severe turmoil. Inflation was rampant and hunger was commonplace in a country rich in natural resources. Some 60 percent of the population lived in poverty and the per capita income was around $70. In the mid 1960s, despite its rich soils, Indonesia had the unusual distinction of being the world's largest importer of rice.

According to a July 1966 report in Time, "On the books Indonesia went bankrupt years ago. It owes $2.4 billion to foreign creditors, and its exports bring in nowhere nearly enough money even to meet interest payments. It has no foreign currency reserves, almost no foreign credit. The rupiah is literally not worth with the paper it is printed on. The cost of living quintupled during the first six months of the year, and there is little hope of stopping its rise."

According to Lonely Planet: “With the elimination of the communists and the establishment of a more repressive government, political stability returned to Indonesia. A determined effort to promote national rather than regional identity was largely successful, but often it was at considerable cost to the population. Infamous examples were the 1975 invasion of East Timor and the brutal treatment of separatist guerrillas in Aceh and Irian Jaya. Smaller scale dissent was also managed through a culture of intimidation and imprisonment.”

Suharto deftly preserved Sukarno’s Pancasila ideology—introduced in 1945 as the nation’s foundational philosophy—comprising five broad principles: belief in God, national unity, humanitarianism, social justice, and democracy. He portrayed his own rule as a pragmatic middle path between communism and Islamism, occasionally targeting overseas Chinese business interests to reinforce this positioning. In 1985, the legislature passed government-backed laws requiring all political parties and organizations to adopt Pancasila as their sole ideological foundation. For Muslim groups, including the PPP, this requirement was highly sensitive because it challenged the religious basis of their identity; the government insisted that Islamic parties abandon exclusivity and admit non-Muslim members. Although Pancasila affirmed belief in a “supreme being,” the use of the term Maha Esa—rather than Allah—was intended to encompass Indonesia’s diverse religious communities, including Christians, Hindus, and Buddhists as well as Muslims. [Source: John Gittings, The Guardian, January 27, 2008; Library of Congress]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUHARTO: HIS LIFE, PERSONALITY AND RISE TO POWER factsanddetails.com

REPRESSION UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

COUP OF 1965 AND THE FALL OF SUKARNO AND RISE OF SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: KILLERS, VICTIMS, REASONS factsanddetails.com

LEGACY OF THE VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: FEAR, FILMS AND LACK OF INVESTIGATION factsanddetails.com

CORRUPTION AND FAMILY WEALTH UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

1997-98 ASIAN FINANCIAL CRISIS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998: PRESSURES, EVENTS, RESIGNATION factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO AFTER HIS RESIGNATION: TRIALS, DEATH, LEGACY, VIEWS, FAMILY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO AS PRESIDENT: CHALLENGES, AUTHORITARIANISM, GUIDED DEMOCRACY factsanddetails.com

Indonesian Government Under Suharto

Many Indonesians referred to Suharto as “Bapak”, or father, or the "puppet master." He established a "culturally neutral authoritarian rule” that was backed up by the military. Elements of Suharto's rule included a military deeply involved in politics and business, patronage, cronyism, indoctrination of school children, democratic smokescreens covering up a rule by a single leader, and "consensus" based on fear and terror.

Pankaj Mishra wrote in The New Yorker: “This bloodletting inaugurated Suharto’s New Order—an even more transparent euphemism for despotism than Sukarno’s Guided Democracy had been. Suharto offered people rapid economic growth through private investment and foreign trade, without any guarantee of democratic rights. Styling himself bapak, or father, of all Indonesians, he proved more successful than other stern paternalists, such as the Shah of Iran and the Philippines’ Ferdinand Marcos. One of his advisers was a close reader of Samuel Huntington’s “Political Order in Changing Societies” (1968). The book’s thesis—that simultaneous political and economic modernization could lead to chaos—was often interpreted in developing countries as a warning against unguided democracy. Suharto, accordingly, combined hard-nosed political domination with an expanding network of economic patronage. In effect, he was one of the earliest exponents of a model that China’s rulers now embody: crony capitalism mixed with authoritarianism. He benefitted from the fact that the massacres had not only disposed of a strong political opposition but also intimidated potential dissenters among peasants and workers. According to Huntington, the historical role of the military in developing societies “is to open the door to the middle class and to close it on the lower class.” Suharto, together with his relatives and allies in the military and in big business, pulled off this tricky double maneuver for more than three decades, helped by the country’s wealth of exportable natural resources (tin, timber, oil, coal, rubber, and bauxite). [Source: Pankaj Mishra, The New Yorker, August 4, 2014]

Suharto’s control of the military was key to his control of Indonesia. He adeptly set off various factions against one another and kept them under a leash by dividing up political power and allowing top military officers to enrich themselves through various enterprises, often in conjunction with Chinese businessmen. Suharto was a skilled behind the scenes politician. While presenting a smiling, jovial face to the public he effectively played factions off one other and was not afraid to harass, intimidate, jail or execute those perceived as a threat. Suharto's real talent lay in manipulating the military elite on which he relied and yet needed to divide and rule. Those he depended on most would found themselves discarded when they threatened to become too powerful.

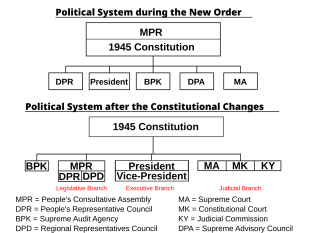

Like Sukarno's Guided Democracy, the New Order under Suharto was authoritarian. There was no return to the relatively unfettered party politics of the 1950-57 period. In the decades after 1966, Suharto's regime evolved into a steeply hierarchical affair, characterized by tight centralized control and long-term personal rule. At the top of the hierarchy was Suharto himself, making important policy decisions and carefully balancing competing interests in a society that was, despite strong centralized rule, still extremely diverse. Arrayed below him was a bureaucratic state in which ABRI played the central role. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Formally, the armed forces' place in society was defined in terms of the concept of dwifungsi. Unlike other regimes in Southeast Asia, such as Thailand or Burma, where military regimes promised an eventual (if long-postponed) transition to civilian rule, the military's dual political-social function was considered to be a permanent feature of Indonesian nationhood. Its personnel played a pivotal role not only in the highest ranks of the government and civil service but also on the regional and local levels, where they limited the power of civilian officials. The armed forces also played a disproportionate role in the national economy through militarymanaged enterprises or those with substantial military interests. *

See Legislature, Government Under Government.

New Order Under Suharto

The New Order was the name given to Suharto’s government. It was a kind of social contract in which Indonesians went along with Suharto's authoritarian ways as long as he brought security, stability and economic growth. The pillars of the New Order were the military officers and Golkar Party cabinet ministers and department heads that ran the government and answered directly to Suharto. Under them were judges, parliament members, top bureaucrats and party officials approved by Suharto.

The New Order established economic rehabilitation and development as its primary goals and pursued its policies through an administrative structure dominated by the military but with advice from Western-educated economic experts. According to Lonely Planet: With Sukarno’s ‘Guided Democracy’ no more; the governing label became ‘The New Order’. Suharto set to mending rifts with the West by changing tack on foreign policy and attracting foreign investment. Dem―ocracy was paid lip service in the 1971 general elections with Suharto’s Golkar Party a sure bet: other parties were banned, candidates disqualified and voters disenfranchised. Predictably, Golkar swept to power. The new People’s Consultative Congress included 207 Suharto appointments and 276 officers from the armed forces. Proclaiming a "new order", Suharto confined domestic politics to setpiece elections contested by two federations of former parties and an army-dominated body, Golkar, which had no party members but won 60 percent to 70 percent of the vote. [Source: Lonely Planet]

Transition from Sukarno to Suharto

The transition from Sukarno's Guided Democracy to Suharto's New Order reflected a realignment of the country's political forces. The left had been bloodied and driven from the political stage, and Suharto was determined to ensure that the PKI would never reemerge as a challenge to his authority. Powerful new intelligence bodies were established in the wake of the coup: the Operational Command for the Restoration of Security and Order (Kopkamtib) and the State Intelligence Coordination Agency (Bakin). The PKI had been crushed on the leadership and cadre levels, but an underground movement remained in the villages of parts of Java that was methodically and ruthlessly uprooted by the end of 1968. Around 200,000 persons were detained by the military after the coup: these were divided into three categories depending on their involvement. The most active, Group A, those "directly involved" in the revolt, were sentenced by military courts to death or long terms in prison; Group B, less actively involved, were in many cases sent to prison colonies, such on Buru Island in the Malukus, where they remained under detention, in some cases until 1980; Group C detainees, mostly members of the PKI peasant organization, were generally released from custody. (As late as 1990, four persons were executed for involvement in the coup. Although the delay was explained as due to the length of the judicial appeals process, many observers believed that Suharto wanted to show that the passage of years had not softened his attitude toward communism.) [Source: Library of Congress *]

Communists aside, Suharto generally dealt with opposition or potential opposition with a blend of cooptation and nonlethal repression. According to political scientist Harold A. Crouch, Suharto's operating principle was the old Javanese dictum of alon alon asal kelakon, or "slow but sure." Thus, he gradually asserted control over ABRI, weeding out pro-Sukarno officers and replacing them with men on whom he could depend. The army was placed in a superior position in relation to the other services in terms of budgets, personnel, and equipment. Nasution, Indonesia's most senior general, was gently pushed aside after he left the post of minister of defense and security to become chairman of the DPR in early 1966. Although he later retired from public life, Nasution remained a potential rival to Suharto although he never publicly spoke out or exploited his favorable popular image. *

On the surface, and particularly through a Cold War lens, the New Order appeared to be the antithesis of the Old Order: anticommunist as opposed to communist-leaning, pro-Western as opposed to anti-Western, procapitalist rather than anticapitalist, and so on. As new head of state, Suharto seemed to reflect these differences by being, as historian Theodore Friend put it, “cold and reclusive where Sukarno had been hot and expansive.” And certainly many Indonesians saw the change of regime as representing a great deal more than a mere shift or transition. Separated from the Old Order by a national trauma, the New Order was unabashedly dominated by the military, focused on economic development (pembangunan), and determined to create stability. The promoters of the New Order saw themselves as pragmatic and realistic, generally apolitical and opposed to all ideologies, characteristics that, in the wake of the Guided Democracy years, were by no means unpopular even among those who were nervous about the prospects of military rule. *

It became obvious in time, however, that alongside the differences there were a number of important similarities between the two regimes. For example, both Sukarno and Suharto developed into authoritarian rulers, compared by critics to ancient Javanese kings and seen as unique and uniquely potent figures—the sole dalang (puppet master)—on whom everything depended. Both men believed in a strong, highly centralized, and religiously neutral state, and both found established political parties and organized public opposition difficult to tolerate. Both searched for and hoped to define an appropriate national identity, looking back to Indonesia’s beginnings as an independent nation for inspiration in so doing. Both men overestimated their own powers and were in the end forced from office and publicly disgraced in ways and for reasons they could not grasp. The two “orders,” like the two individuals who epitomized them, are best viewed not in either/or terms, but in the light of nuance and an awareness of similarities and differences, changes and continuities.

It was still far from clear in 1966, either to Suharto himself or to his civilian and military supporters, what the New Order was actually going to look like. At a seminar entitled “In Search of a New Path” held at Jakarta’s Universitas Indonesia in May that year, students and intellectuals grappled primarily with problems associated with the economy, focusing on the role that could be played by those with specialized training in economic development and finance, so-called technocrats. Three months later, the armed forces, under Suharto’s leadership, held their own seminar in Bandung, entitled “Broad Policy Outlines and Implementation Plans for Political and Economic Stability.” There was extended discussion, with civilian leaders in attendance, of the appropriate role of the military in rebuilding Indonesia. They settled on “safeguarding the Revolution,” and exercising dwifungsi (dual function) of national defense and participation in the nation’s political and social affairs, twin responsibilities said to be rooted in the army’s experience during the struggle for independence (see Suharto’s New Order). There were vague references at this time to elections, but it was reasonably clear that there would be no return to the open party politics of the early 1950s, which military, and many civilian, leaders considered divisive because they either tapped into “primordial” loyalties and identities or created such loyalties on the basis of inappropriate ideologies. On the other hand, Sukarno’s Guided Democracy had proven unworkable. The New Order solution was to attempt an apolitical, nonideological, quasi- or pseudo- democratic system that would promote unity, prevent both internal conflict and the obstruction of economic development, and satisfy some of the basic requirements of world opinion.

Stability Under Suharto

Although opposition movements and popular unrest were not entirely eliminated, Suharto's regime was extraordinarily stable compared with its predecessor. His success in governing the world's fourth most populous and, after India, ethnically most diverse nation is attributable to two factors: the military's absolute or near-absolute loyalty to the regime and the military's extensive political and administrative powers. In the mid-1980s, approximately 85 percent of senior officers were Javanese (although the percentage was declining). Suharto wisely averted a problem of many military regimes: the monopolization of the higher ranks by senior military officers who frustrate the aspirations of their juniors. In 1985 he ordered an extensive reorganization of the officer corps in which the Generation of 1945, who had taken part in the National Revolution, was largely retired, the younger generation promoted into command positions, and an extensive reorganization accomplished in order to promote efficiency. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Other factors in stability include the establishment of a large number of corporatist-style organizations to link social groups in a subordinate relationship with the regime. These included organizations of a social, class, religious, and professional nature. Rather than imposing cultural and ideological homogeneity — a virtually impossible task given the society's diversity — Suharto revived the Sukarno-era concept of Pancasila. Suharto's approach to political conflict did not reject the use of coercion but supplemented it with a rhetoric of "consultation and consensus," which, like Pancasila, had its roots in the Sukarno and Japanese eras. *

The Jakarta Post reported: “He has always maintained a quiet style featuring personal restraint and discipline. This low-key personal approach coupled with great power enabled unimpeded political navigation to secure his position. He showed patience and grace under pressure. Soeharto never showed panic, morphing from public enemy to elder statesman without leaving his home. Foreign investors admired him and even now associate him with stability and prosperity.”[Source: Jakarta Post, May 23, 2005]

The New Order probably reached the peak of its powers in the mid- to late 1980s. The clear success of its agricultural strategy, achieving self-sufficiency in rice in 1985, and its policies in such difficult fields as family planning—Indonesia’s birthrate dropped exceptionally rapidly from 5.5 percent to 3.3 percent annually between 1967 and 1987—earned it international admiration. Economic progress for the middle and lower classes had seemed to balance any domestic discontent.

Political Structure Under Suharto

What came to be called Pancasila Democracy appears to have been constructed principally by Ali Murtopo (1924–84), a long-time army associate of Suharto. Of modest social and educational background, Ali Murtopo rose to prominence in the military, primarily as an “operator” with strategic sense and a “can do” attitude. His role as a leading military intelligence officer earned him a reputation as an unscrupulous and rather mysterious manipulator, but in some respects he mirrored views held far beyond a small group of military leaders and shared among the civilian middle classes, and his activities were widely known. His plan had three key elements. First, government control of the parliamentary process would be achieved by stipulating that a certain percentage of the membership of the chief legislative body, the People’s Representative Council (DPR), and the chief representative body, the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR), were to be government civilian appointees, with an additional group of appointed members from the armed forces. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Second, control of the electoral process would come by limiting the number of political parties and prying them away from ethnic, religious, regional, or personal identities, as well as by establishing a government-backed parliamentary representative group (pointedly not a “political party”) of government employees and other groups, such as Golkar, an organization of functional groups, to participate in elections. Third, control over the majority of the voting public would result from limiting the periods of political campaigning and restricting such activities to the district level. The inhabitants of villages and small towns—the majority of Indonesians—were to be “freed” from mass political mobilization, manipulation, and polarization, becoming instead a more or less depoliticized “floating mass.” They would be encouraged to vote for whichever party or group they thought might best answer their needs at the moment, but not to make their choices on the basis of “primordial” or personal identifiers. *

An additional component, designed initially under the direction of Ruslan Abdulgani (1914–2005), who had served as Sukarno’s chief ideological adviser a decade earlier, was a national indoctrination program intended to give Pancasila clarity and application, and to ensure that all Indonesians uniformly understood and accepted it. The military, the extraconstitutional Kopkamtib, and the civilian National Intelligence Coordinating Board (Bakin) all exerted degrees of watchfulness and enforcement. These arrangements, which came to characterize the New Order, did not emerge suddenly and fully formed but rather were the product of gradual change and, generally, pragmatic adjustment. The consolidation of political parties, for example, did not take place until 1973, two years after the first elections (in which Golkar won nearly 63 percent of the vote). *

Particularly after its first decade and down until its final years, the New Order’s political design gave the impression that it had produced a tight, highly centralized, and closely managed system, and one that depended to an extraordinary degree on the political genius of one individual, Suharto. Scholars and others, especially those who opposed the rise of the New Order, struggled to find an appropriate term with which to describe it—autocratic, militarist, neofeudal, patrimonial, paternalist, neofascist, corporatist, military-bureaucratic, developmentalist, or command-pragmatist—and periodically announced that its demise was imminent. None of the terms proved altogether satisfactory, but even so the New Order lasted for 32 years.

The continuity of the New Order was not achieved solely, or perhaps even largely, by force or the threat of force. For one thing, Indonesia was far too large and too diverse to be ruled entirely uniformly by a single institution, much less a single person. As political scientist Donald K. Emmerson noted in 1999, “‘Suharto’s Indonesia’ had never been more than a metaphor.” Further, the military itself was neither monolithic nor a caste apart from civilian society. The actual practice of dwifungsi, which by 1969 had, for example, placed military men as governors in nearly 70 percent of the nation’s provinces and as mayors and district heads in more than half of all cities and districts, did more to “civilianize” the military than to militarize civil society. And it was under “military rule” that the civilian bureaucracy ballooned, between 1975 and 1988 more than doubling to 3.5 million. It is also true that the New Order was founded, and continued to depend upon, a rough and largely unspoken consensus among the middle classes, military as well as civilian, that economic development came before everything else. The New Order government had a great deal of leeway as long as it could make good on promises of economic growth. *

None of this meant, however, that government policies and actions went unopposed. Indeed, the period of greatest political structural change and economic expansion saw serious outbursts of dissent: the 1974 Malari riots over big business and the burgeoning Japanese economic presence were followed in 1976 by the Sawito Affair accusing Suharto and the government of corruption. In 1980 came the Petition of 50 in which notables, many of them former ABRI officers and close allies of Suharto, protested that the New Order had misinterpreted Pancasila and misunderstood the proper mission of the armed services, and in 1984 the Tanjung Priok riots protested corruption and ABRI’s handling of Islam. These upheavals were handled in coarse, often coercive, ways. But they could be weathered because a broad public feared unrest and had made a certain peace with the supposition, long nursed in both military and some civilian circles, that potential enemies to national order included not only communism and Islam but also unfettered Western-style liberal democracy. *

Political Parties Under Suharto

Suharto’s Golkar Party was a creation of Suharto and the military. It maintained control over Indonesia’s far flung islands by controlling funding to government agencies on these islands and operating a system of patronage based on personality and rewards. Suharto then enforced the merger of other political parties. The four Islamic parties were amalgamated into the Development Unity Party (PPP) and the other parties were formed into the Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI).

Suharto's regime transformed and marginalized political parties, which, minus the PKI, still retained considerable popular support in the late 1960s. Party influence was diminished by limiting the parties' role in newly established legislative bodies, the DPR and the MPR, about 20 percent of whose members were appointed by the government. Parties were forced to amalgamate: in January 1973, four Islamic parties were obliged to establish a single body known as the Unity Development Party (PPP) and nonIslamic parties, including the PNI, were obliged to merge into the Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI). Established by the armed forces in 1964, the Joint Secretariat of Functional Groups (Golkar) was given a central role in rallying popular support for the New Order in carefully staged national legislative elections. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The consolidation of political parties took place in 1973, two years after the first elections. Government strategists seem to have thought consolidation might be preferable to the direct but clumsy manipulation of party leadership attempted before the elections. A strong fear persisted that, even with communism outlawed, potential threats to order remained in the form of religiously identified parties and the former followers of Sukarno. Islamic parties had to combine, for this reason, in a government-created Development Unity Party (PPP), and other parties, including Sukarno’s old PNI, amalgamated in the Indonesian Democracy Party (PDI). Where Pancasila was concerned, the government attempted to introduce draft bills on the subject in 1969 and 1973, but nothing came of them. It was only in 1978 that moral instructions, the so-called Guide to Realizing and Experiencing the Pancasila (P4), took shape, and Pancasila education began to enter school curricula and civil service training in earnest. Not until 1985 did all organizations, including political groups, have to adopt the Pancasila as their asas tunggal (underlying principle). *

Designed to bring diverse social groups into a harmonious organization based on "consensus," by 1969 Golkar had a membership of some 270 associations representing civil servants, workers, students, women, intellectuals, and other groups. Backed both financially and organizationally by the government, it had mastered Indonesia's political stage so completely by the 1970s that speculation centered not on whether it would gain a legislative majority, but on how large that majority would be and how the minority opposition vote would be divided between the PPP and the PDI. *

Elections Under Suharto

Elections under Suharto were bogus contests between members of two or three government-sanctioned parties with a preordained winner—Suharto's ruling Golkar Party won every election — six in total between 1971 and 1998. Suharto himself was elected to seven five-year terms. The Suharto government controlled elections by restricting campaign activities, banning parties and disqualifying candidates, vetting candidates for all three parties and even reviewing speeches.

Suharto was elected president in 1968 and reelected in 1973, 1978, 1983, 1988, 1993, and 1998. In the general elections of 1971, 1977, and 1982, Golkar won 62.8, 62.1, and 64.3 percent of the popular vote, respectively. In the 1971 election, Golkar won by an overwhelming margin and the PNI, Sukarno’s party, fared poorly and was effectively eliminated as a political threat. The new legislature contained 276 military officers and 207 Suharto appointees. Afterward the four Muslim parties were forced ti merge into a single part, the Development Union Party (PPP), and the other parties merged into the Indonesian Democratic party (PDI).

Golkar won the next election in 1977, and it took the majority of the seats in the House of Representatives. Its political dominance continued until the regime was toppled the late 1990s. In the 1992 election, Suharto's Golkar party won 68 percent of the vote. The United Development Party won 17 percent and the People's Democratic Party won 15 percent. Suharto was reappointed as head of the Golkar by the People's Consultive Assembly in 1993. In 1998, the Golkar party won 87 percent of the vote.

According to the constitution the vice president takes power if the president dies in office. Six vice presidents served under Suharto and none was allowed to stay on for a second term. After his "re-election" in early 1998, Suharto named his golf buddy as Trade and Interior minister and his daughter as Minister of Social Welfare.

Suharto in the 1970s and 80s

In March 1973, the MPR elected Suharto to a second five-year term, marking the start of his long dominance over Indonesian politics, backed decisively by the military. Under his “New Order,” Indonesia reoriented itself toward the West and adopted a conservative economic program focused on capital development and foreign investment. Suharto’s government also strengthened relations with the United States, Japan, and Western Europe, while continuing to maintain ties with the Soviet Union. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Discontent with Suharto’s rule grew after the 1977 elections, in which his Golkar Party won an overwhelming majority. The government admitted holding 31,000 political prisoners, though Amnesty International estimated the figure at closer to 100,000. Student protests and criticism of government repression led to further crackdowns, including the suspension of political activity and temporary shutdowns of major newspapers. Suharto secured a third term in 1978. Between late 1977 and 1979, about 16,000 political prisoners were released, and the remaining detainees from 1965 were freed by the end of 1979.

Golkar strengthened its position in the 1982 elections, and Suharto secured a fourth presidential term in March 1983. To bolster his government amid rising Muslim militancy, Suharto began rehabilitating Sukarno’s image, declaring the late leader a national hero eight years after his death. He also urged all political groups to reaffirm their loyalty to Pancasila—the “five principles” Sukarno articulated in 1945: belief in a single supreme deity, humanitarianism, national unity, consensus-based democracy, and social justice. Many Muslim organizations objected strongly to this initiative, leading to demonstrations in 1984 and 1985.

The conflict in East Timor persisted into the 1980s, with reports of massacres by Indonesian forces and widespread economic suffering among the Timorese. Negotiations with Portugal—still recognized by the UN as the territory’s administering power—began in July 1983. In Irian Jaya, the separatist Organization for a Free Papua (OPM), active since the early 1960s and seeking unification with Papua New Guinea, intensified its militant activities in 1986.

The Indonesian Army (ABRI) continued to exercise its dual military and sociopolitical role, a position reinforced through 1988 legislation. Golkar scored additional gains in the 1987 elections, and Suharto was reelected to a fifth term in March 1988. However, disputes over the selection process for the vice presidency during this period contributed to an erosion of ABRI’s political influence.

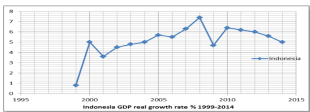

Development Under Suharto

Suharto brought stability, economic development, family planning and widespread literacy to Indonesia. He built schools and highways and improved Indonesia's financial institutions and communications systems. For a long time, Indonesia seemed like a model of Third World development. The economy grew while population growth, poverty, and illiteracy were reduced.

Despite widespread human-rights abuses, the New Order presided over significant social and economic development. Suharto pledged to improve the welfare of ordinary Indonesians, and in many respects succeeded. Shortly after taking office, Suharto launched the "New Program," whose aim was to develop the country and leave the Sukarno anti-Western era behind In the 1960s and 70s, Indonesia encouraged rural development and invested heavily in education, health care, family planning and infrastructure. Planners also wisely did not pacify urban constituencies by keeping down food prices at the expense of peasant farmers. Rice production exploded and the ground was set for years of steady growth,

Major advances in agriculture, education, and basic infrastructure marked the period. New roads, medical clinics, schools, and bridges reached remote regions of the archipelago, helping create a more literate and Indonesian-speaking generation. These accomplishments were especially notable given the country’s vast geography and ethnic diversity. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Thanks mainly to an oil boom and new strains of rice (‘the Green Revolution’), the lot of many Indonesians improved considerably under Suharto. Under Suharto, all but 10 percent of Indonesia's 210 million rose above the poverty line, the per capita income jumped from $50 in 1965 to $1,300 in 1997, the literacy rate jumped from 43 percent to 90 percent. There were more television (46,000 in the 1960s and 12 million in the 1990s) and more doctors (27,614 people per doctor in the 1960s and 6,861 doctors per people in the 1990s). But while life became more tolerable for the poor, the rich became much richer.

Suharto’s administration revived the earlier Dutch policy of “transmigration,” relocating farmers from densely populated Java and Bali to sparsely populated regions such as Kalimantan, Sumatra, and Indonesian New Guinea. The program produced mixed results: although more than six million people had moved by the 1990s, Java and Bali remained heavily populated. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Economy Under Suharto

Apart from rejection of leftism, probably the single greatest discontinuity between the Sukarno and Suharto eras was economic policy. Sukarno abused Indonesia's economy, undertaking ambitious building projects, nationalizing foreign enterprises, and refusing to undertake austerity measures recommended by foreign donors, because such measures would have weakened his support among the masses. Suharto also used the economy for political ends, but initiated a generally orderly process of development supported by large infusions of foreign aid and investment. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Debt service obligations in 1966 exceeded export earnings, and total foreign debt was US$2.3 billion. One billion dollars of this amount was owed to the Soviet Union and its East European allies, largely for arms purchases. The following year, talks were initiated with Western and Japanese creditors for aid and new lines of credit. An informal group of major Western nations, Japan, and multilateral aid agencies such as the World Bank, known as the Inter-Governmental Group on Indonesia (IGGI), was organized to coordinate aid programs. Chaired by the Netherlands, IGGI gained tremendous, and sometimes resented, influence over the nation's economic policymaking. Hand-in-hand with aid donors, a new generation of foreign-educated technocrats — economic planners attached principally to the National Development Planning Council (Bappenas) led by Professor Widjojo Nitisastro — designed and implemented a series of five-year plans. The first plan, Repelita I, which occurred in fiscal year (FY) 1969-73, stressed increased production of staple foods and infrastructure development; Repelita II (FY 1974-78) focused on agriculture, employment, and regionally equitable development; Repelita III (FY 1979-83) emphasized development of agriculture-related and other industry; Repelita IV (FY 1984-88) concentrated on basic industries; and Repelita V (FY 1989-93) targeted transport and communications. During the 1980s, these plans also provided a greater role for private capital in industrialization). *

Indonesia’s economy expanded rapidly in the 1970s, driven by rising oil, gas, and timber exports. With the help of American-trained economists, Indonesia moved from being the world’s largest rice-importing nation to a rice exporter. When oil prices shot up in the 1970s, Suharto's government was able to use the money to build schools, power plants, roads, telecommunications and other infrastructure. Oil revenues quadrupled during the 1973 global "oil shock," Indonesia emerged from pauperdom to modest prosperity. The development of new, high-yield varieties of rice and government incentive programs enabled the nation to become largely self-sufficient in this staple crop. In most areas of the archipelago, standards of nutrition and public health improved substantially. But when Pertamina, the national oil company, was embroiled by scandal in the late 1970s, the country again neared bankruptcy.When prices collapsed in the 1980s, Indonesia was able to move into the manufacturing of shoes, clothing and electronics. By the 1980s and 1990s, export-oriented manufacturing had become increasingly significant.

Oil revenues were vital for the Suharto regime because they provided it with resources to compensate groups whose cooperation was essential for political stability. Government projects and programs expanded impressively. Indonesia is a member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Reflecting OPEC's pricing policies, the state's income from oil, channelled through the state-owned enterprise Pertamina (the National Oil and Natural Gas Mining Company), increased 4,000 percent between the FY 1968 and FY 1985. Economic planners realized, however, the danger of depending excessively on this single source of export revenue, particularly when crude oil prices declined during the mid- and late 1980s. As a result, the export not only of manufactured goods but also of non-oil raw and semiprocessed materials such as plywood and forest products was promoted.

Foreign Policy under Suharto

Indonesia's foreign relations after 1966 can be characterized as generally moderate, inclined toward the West, and regionally focused. As a founding member of the Nonaligned Movement in 1961, Indonesia pursued a foreign policy that in principle kept it equidistant from the contentious Soviet Union and the United States. It was, however, dependent upon Japan, the United States, and West European countries for vital infusions of official development assistance and private investment. Jakarta's perceptions that China had intervened substantially in its internal affairs by supporting the PKI in the mid-1960s made the government far less willing to improve relations with Beijing than were other members of ASEAN. Although Indonesia differed with its ASEAN counterparts over the appropriate response to the Cambodian crisis after the Vietnamese invasion of that country in 1978, its active role in promoting a negotiated end to the Cambodian civil war through the Jakarta Informal Meetings in 1988 and 1989 reflected a new sense of confidence. Policy makers believed that since the country had largely achieved national unity and was making ample progress in economic development, it could afford to devote more of its attention to important regional issues. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Given Indonesia's strategic location at the eastern entrance to the Indian Ocean, including command of the Malacca and Sunda straits, the country has been viewed as vital to the Asian security interests of the United States and its allies. Washington extended generous amounts of military aid and became the principal supplier of equipment to the Indonesian armed forces. Because of its nonaligned foreign policy, Jakarta did not have a formal military alliance with the United States but benefited indirectly from United States security arrangements with other states in the region, such as Australia and the Philippines. The New Order's political repressiveness and its pacification of East Timor, however, were criticized directly and indirectly by some United States officials, who in the late 1980s began calling for greater openness. *

In terms of international economics, Indonesia's most important bilateral relationship was with Japan. During the 1970s, it was the largest recipient of Japanese official development assistance and vied with China for that distinction during the 1980s. Tokyo's aid priorities included export promotion, establishment of an infrastructure base for private foreign investment, and the need to secure stable sources of raw materials, especially oil but also aluminum and forest products. Jakarta depended on aid funds from Tokyo to build needed development projects. This symbiotic relationship, however, was not without its tensions. Indonesian policy makers questioned the high percentage of Japanese aid funds in the form of loans rather than grants and the heavy burden of repaying yen-denominated loans in the wake of the appreciation of the Japanese currency in 1985. Although wartime memories of the Japanese occupation were in general not as bitter as in countries such as the Philippines, Malaysia, and China, there was some concern about the possibility of Japanese remilitarization should United States forces be withdrawn from the region. In the context of Indonesia's long history, the forces bringing about greater integration with the international community while creating political and economic tensions at home were not unexpected. Historians of the twenty-first century are likely to find remarkably similar parallels with earlier periods in Indonesia history. *

Suharto, Communism and the U.S.

Instead of relying on the Soviet Union and other Communist nations for financial support, Suharto turned to the West and sought support from capitalist institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. Spurred by huge revenues from oil an gas exports, Indonesia took out numerous loans for development project but then amassed huge foreign debts with these institutions after the collapse of oil prices.

Suharto, a staunch anti-communist, rose to power in 1968 with U.S. support. Suharto restored relations with the West and implemented market reforms that dramatically improved the living standards of his people. After the Vietnam War, Suharto was a major force on the Associations of Southeast Asian Nations, which promoted capitalism in the region. Indonesia was regarded as a bulwark against Chinese expansion and played a major role in negotiating a settlement in Cambodia. When Suharto visited the U.S. in 1982, Reagan said, "The United States applauds Indonesia's quest for what you call 'national resilience.'" Anti-Communism was major pillar of the Suharto regime. When the Berlin Wall came down, that pillar was no longer relevant.

Marilyn Berger wrote in the New York Times: “Whether it was those forces or his timing, good fortune came to him. Just as the United States was becoming embroiled in Vietnam, he stood as a bulwark against Communism in Asia. The United States rewarded him with a foreign aid program that eventually amounted to more than $4 billion a year. In addition, a consortium of Western countries and Japan established an aid program that in 1994 alone totaled almost $5 billion. In doing so, the United States, along with much of the rest of the world, showed a willingness to overlook the corruption, favoritism and violations of human rights, including the disappearance of opposition politicians, that came to characterize Mr. Suharto’s rule. [Source: Marilyn Berger, New York Times, January 28, 2008]

John Gittings wrote in The Guardian, “Under Suharto, Indonesia enjoyed a favourable international climate. His regime was applauded by the west for its "suppression of communism", a policy the US covertly encouraged. It also won approval from Moscow, which had regarded the PKI's close links with China with alarm. Over the following decade, US oil companies invested more than $2 billion in Indonesia's petroleum industry, accounting for 90 percent of the country's total production. Suharto gained his biggest reward for destroying the Indonesian left when he invaded East Timor in December 1975, only a day after the US president, Gerald Ford, and his secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, had dined with him. As secret documents obtained in 2001 by the independent Washington-based National Security Archive would reveal, Suharto asked for US "understanding if we deem it necessary to take rapid or drastic action". In reply, Ford told Suharto: "We will understand and will not press you on the issue." [Source: John Gittings, The Guardian, January 27, 2008]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025