YEAR OF LIVING DANGEROUSLY

The transition between Sukarno and Suharto was marked some of the worst episodes of violence in the 20th century and was a key event in the Cold War era. A period of mass killings were triggered by a failed uprising by Indonesian armed officers who kidnapped and executed six army generals beginning on the night of September 30, 1965, and continuing into the early hours of October 1. Afterwards then-General Suharto and other top commanders quashed the uprising, which they called an attempted coup orchestrated by the powerful Indonesian Communist Party. The period of instability was dramatized in the film “Year of Living Dangerously” with Mel Gibson and Sigorney Weaver. In a famous speech Sukarno used the term the “year of living dangerously” to exhort Indonesians to prepare for hard times ahead. Fourteen months after Sukarno’s famous the violence began.

Suharto was able to ease Sukarno off the scene with a minimum of bloodshed but then embarked on a ruthless campaign of bloodletting against 3 million Communists and suspecting leftists. An estimated 300,000 to 1 million Indonesians were killed. Even though Chinese were often the targets of the anti-Communist purges most of the deaths were indigenous Indonesians. The CIA called it “one of the worst mass murders of the twentieth century, along with the Soviet purges of the 1930s, the Nazi mass murders during the Second World War, and the Maoist bloodbath of the early 1950s.” By some estimates approximately half a million members of the Indonesian Communist Party (Partai Komunis Indonesia, PKI) were killed by army units and anticommunist militias.

The circumstances surrounding the abortive coup d'état of September 30, 1965 — an event that led to Sukarno's displacement from power; a bloody purge of PKI members on Java, Bali, and elsewhere; and the rise of Suharto as architect of the New Order regime — remain shrouded in mystery and controversy. The official and generally accepted account is that procommunist military officers, calling themselves the September 30 Movement (Gestapu), attempted to seize power. Capturing the Indonesian state radio station on October 1, 1965, they announced that they had formed the Revolutionary Council and a cabinet in order to avert a coup d'état by corrupt generals who were allegedly in the pay of the United States Central Intelligence Agency. The coup perpetrators murdered five generals on the night of September 30 and fatally wounded Nasution's daughter in an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate him. Contingents of the Diponegoro Division, based in Jawa Tengah Province, rallied in support of the September 30 Movement. Communist officials in various parts of Java also expressed their support. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Book: “The Year of Living Dangerously” by C.J. Koch. Film: “The Year of Living Dangerously, with Mel Gibson, is one of the few Western films set in Indonesia. This movie takes place during Suharto’s rise to power in 1966.

RELATED ARTICLES:

COUP OF 1965 AND THE FALL OF SUKARNO AND RISE OF SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

LEGACY OF THE VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: FEAR, FILMS AND LACK OF INVESTIGATION factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO: HIS LIFE, PERSONALITY AND RISE TO POWER factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO AS PRESIDENT: CHALLENGES, AUTHORITARIANISM, GUIDED DEMOCRACY factsanddetails.com

DIFFICULTY MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK IN INDONESIA IN THE 1950s factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA DECLARES INDEPENDENCE IN 1945 AT THE END OF WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA’S NATIONAL REVOLUTION: THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE 1945-1949 factsanddetails.com

INDONESIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE (1945-1949): POLICE ACTION, ATROCITIES, MASSACRES factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA OFFICIALLY ACHIEVES INDEPENDENCE factsanddetails.com

Crackdown on Communists After the 1965 Failed Coup

After the October 1965 failed coup the Communist party was banned "amid a purge of suspected leftist carried out by the army and conservative Muslims, who accused the Communist of promoting atheism. The generals who orchestrated the crackdown were secretly aided the U.S. government, which gave them money and supplied them with the names and whereabouts of key Communist leaders. During this period, tens of thousands of PKI members turned in their membership cards.

More than 700,000 people were arrested. After the crackdown, purge and reign of terror, there were very few Communists were left. Some 600,000 suspected Communist were detained without being charged, many for years. As of 1975, ten years after the Communist coup, the Indonesian government still held 70,000 political prisoners, most of whom were never were given a trial. The Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity reported: According to official figures, between 600,000 and 750,000 people passed through detention camps for at least short periods after 1965, though some estimates are as high as 1,500,000. These detentions were partly adjunct to the killings—victims were detained prior to execution or were held for years as an alternative to execution—but the detainees were also used as a cheap source of labor for local military authorities. Sexual abuse of female detainees was common, as was the extortion of financial contributions from detainees and their families. Detainees with clear links to the PKI were dispatched to the island of Buru, in eastern Indonesia, where they were used to construct new agricultural settlements. Most detainees were released by 1978, following international pressure. [Source: Robert Cribb, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

Acclaimed Indonesian writer and detainee Pramoedya Ananta Toer wrote in Time: "During the first days of October, Armed Forces chief General Nasution made commando-like speeches on the radio, urging the public to 'destroy the Communist Party root and branch.' After these pronouncements, the murder, looting and burning of the army intensified to the point of insanity. For 13 days after the coup was launched "I watched the army hunt, murder and loot until, finally, I myself became one of the victims. People known or suspected to be communist or sympathizers were slaughtered everywhere they were found—on the steps of their houses, on the side of the road, while squatting in the lavatory. The Indonesian elites had lost their ability to resolve differences peacefully, in the political sphere, and the last word belonged to the group that possessed firearms: the army...On October 13, 1965, it was my turn to be targeted by a pack of armed, masked men. There was no official, written charges...When I was arrested in October 1965, my study was ransacked and all my papers were destroyed, including unpublished manuscripts."

Violence After the September 1965 Attempted Coup

In the wake of the September 30 coup's failure, there was a violent anticommunist reaction throughout Indonesia. Rightwing gangs killed tens of thousands of alleged communists in rural areas. The violence was especially brutal in Java and Bali. By December 1965, mobs were engaged in large-scale killings, most notably in Jawa Timur Province and on Bali, but also in parts of Sumatra. Members of Ansor, the Nahdatul Ulama's youth branch, were particularly zealous in carrying out a "holy war" against the PKI on the village level. Chinese were also targets of mob violence. Estimates of the number killed — both Chinese and others — vary widely, from a low of 78,000 to 2 million; probably somewhere around 300,000 is most likely. Whichever figure is true, the elimination of the PKI was the bloodiest event in postwar Southeast Asia until the Khmer Rouge established its regime in Cambodia a decade later. [Source: Library of Congress]

According to Lonely Planet: Following the army’s lead, anticommunist civilians went on the rampage. In Java, where long-simmering tensions between pro-Islamic and pro-communist factions erupted in the villages, both sides believed that their opponents had drawn up death lists to be carried out when they achieved power. The anticommunists, with encouragement from the government and even Western embassies, carried out their list of executions. On top of this uncontrolled slaughter there were violent demonstrations in Jakarta by pro- and anti-Sukarno groups. Also, perhaps as many as 250,000 people were arrested and sent without trial to prison camps for alleged involvement in the coup. [Source: Lonely Planet]

The American anthropologist Clifford Geertz wrote: “Everyone as terrified. A Communist leader’s head was hung up in the doorway of his headquarters, another was hung on the footbridge in front of his house with a cigarette stuck between his teeth . There were legs and arms and torsos every morning in the irrigation canals. Penises were nailed to telephone poles.”

Why Were the Indonesian Communists Targeted

By 1965 Indonesia had become a dangerous cockpit of social and political antagonisms. The PKI's rapid growth aroused the hostility of Islamic groups and the military. The ABRI-PKI balancing act, which supported Sukarno's Guided Democracy regime, was going awry. One of the most serious points of contention was the PKI's desire to establish a "fifth force" of armed peasants and workers in conjunction with the four branches of the regular armed forces. Many officers were bitterly hostile, especially after Chinese premier Zhou Enlai offered to supply the "fifth force" with arms. By 1965 ABRI's highest ranks were divided into factions supporting Sukarno and the PKI and those opposed, the latter including ABRI chief of staff Nasution and Major General Suharto, commander of Kostrad. Sukarno's collapse at a speech and rumors that he was dying also added to the atmosphere of instability. [Source: Library of Congress]

Ellen Nakashima wrote in the Washington Post: “Throughout the early 1960s, bad feelings built between the Communist Party, which supported land reform in rural areas, and small landlords. In October 1965, following the murder of six top generals under murky circumstances, Suharto took control of the Indonesian army. The army then waged a ruthless campaign to wipe out the Communist Party and its supporters, who were blamed for the murders. Though the party members were nominally Muslim in this predominantly Muslim country, their opponents demonized them as bloodthirsty atheists bent on seizing land and power. For a long time, schoolchildren were shown a documentary each year that blamed the generals' murders on the Communist Party, though who really was at fault is still debated by historians. State media reported that Communist women danced as the generals were castrated and their eyes gouged out. Despite autopsies showing no torture or mutilation, the myth has never been corrected in text books or films and still has currency. [Source: Ellen Nakashima, Washington Post Foreign Service, October 30, 2005 /+]

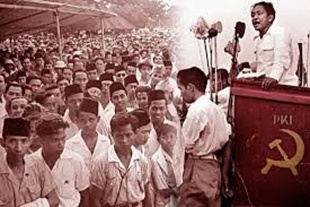

According to the Encyclopedia of Genocide: At the time of its destruction, the PKI was the largest communist party in the non-communist world and was a major contender for power in Indonesia. President Sukarno's Guided Democracy had maintained an uneasy balance between the PKI and its leftist allies on one hand and a conservative coalition of military, religious, and liberal groups, presided over by Sukarno, on the other. Sukarno was a spellbinding orator and an accomplished ideologist, having woven the Indonesia's principal rival ideologies into an eclectic formula called NASAKOM (nationalism, religion, communism), but he was ailing, and there was a widespread feeling that either the communists or their opponents would soon seize power. [Source: Robert Cribb, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

The PKI was a dominant ideological stream. Leftist ideological statements permeated the public rhetoric of Guided Democracy, and the party appeared to be by far the largest and best-organized political movement in the country. Its influence not only encompassed the poor and disadvantaged but also extended well into military and civilian elites, which appreciated the party's nationalism and populism, its reputation for incorruptibility, and its potential as a channel of access to power. Yet the party had many enemies. Throughout Indonesia, the PKI had chosen sides in long-standing local conflicts and in so doing had inherited ancient enmities. It was also loathed by many in the army for its involvement in the 1948 Madiun Affair, a revolt against the Indonesian Republic during the war of independence against the Dutch. Although the party had many sympathizers in the armed forces and in the bureaucracy, it controlled no government departments and, more important, had no reliable access to weapons. Thus, although there were observers who believed that the ideological élan of the party and its strong mass base would sweep it peacefully into power after Sukarno, others saw the party as highly vulnerable to army repression. A preemptive strike against the anticommunist high command of the army appeared to be an attractive strategy, and indeed it seems that this was the path chosen by Aidit, who appears to have been acting on his own and without reference to other members of the party leadership.

Reasons for the Violent Crackdown on Indonesia Communists in 1965-66

Robert Cribb wrote in the Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity: The catalyst for the killings was a coup in Jakarta, undertaken by the September 30 Movement, but actually carried out on October 1, 1965. Although many aspects of the coup remain uncertain, it appears to have been the work of junior army officers and a special bureau of the PKI answering to the party chairman, D. N. Aidit. The aim of the coup was to forestall a predicted military coup planned for Armed Forces Day (October 5) by kidnapping the senior generals believed to be the rival coup plotters. After some of the generals were killed in botched kidnapping attempts, however, and after Sukarno refused to support the September 30 Movement, its leaders went further than previously planned and attempted to seize power. They were unprepared for such a drastic action, however, and the takeover attempt was defeated within twenty-four hours by the senior surviving general, Suharto, who was commander of the Army's Strategic Reserve, KOSTRAD. [Source: Robert Cribb, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

“There was no clear proof at the time that the coup had been the work of the PKI. Party involvement was suggested by the presence of Aidit at the plotters' headquarters in Halim Airforce Base, just south of Jakarta, and by the involvement of members of the communistaffiliated People's Youth (Pemuda Rakyat) in some of the operations, but the public pronouncements and activities of the September 30 Movement gave it the appearance of being an internal army movement. Nonetheless, for many observers it seemed likely that the party was behind the coup. In 1950 the PKI had explicitly abandoned revolutionary war in favor of a peaceful path to power through parliament and elections. This strategy had been thwarted in 1957, when Sukarno suspended parliamentary rule and began to construct his Guided Democracy, which emphasized balance and cooperation between the diverse ideological streams present in Indonesia.

Uncontrolled violence has played a major role in Indonesia’s modern history. Kerry Brown wrote in the Asian Review of Books, “As Clausewitz famously argued, war is the continuation of politics by other means—and...violence, historically, and in contemporary Indonesia, has performed a continuing political function. Any attempt to understand modern Indonesian history without recognising the prominent role of violence would be incomplete. Part of the cause of this violence derives from the tensions in the impossible complexity of Indonesia—a colonial creation with 17,000 islands (the exact figure seems impossible to calculate) forged by the three centuries of control by the Dutch and the Japanese invasion in the 1940s, and then in the struggle for national liberation after the second world war, and resolved finally by the ‘mystic’ ruler Sukarno and his creation of the ‘new Indonesia’ between 1945 and 1950. It is hardly surprising that there has been so much scope for conflict and strife in a territory that stretches a distance the equivalent of London to Moscow, and which embraces hundreds of different languages, ethnicities, religious beliefs and cultures. [Source: Kerry Brown, Asian Review of Books, May 4, 2005]

Was the October 1985 Coup Set-Up as an Excuse to Crack Down on the Communists?

Robert Cribb wrote: “The military opponents of the PKI had been hoping for some time that the communists would launch an abortive coup, believing that this would provide a pretext for suppressing the party. The September 30 Movement therefore played into their hands. There is evidence that Suharto knew in advance that a plot was afoot, but there is neither evidence nor a plausible account to support the theory, sometimes aired, that the coup was an intelligence operation by Suharto to eliminate his fellow generals and compromise the PKI. Rather, Suharto and other conservative generals were ready to make the most of the opportunity which Aidit and the September 30 Movement provided. [Source: Robert Cribb, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

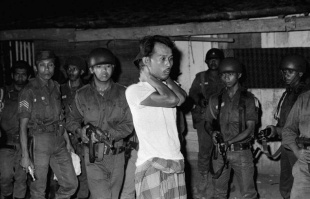

Chinese Indonesian student at Res Publica University who attacked by a crowd and then led away by soldiers, October 15, 1965

“The army's strategy was to portray the coup as an act of consummate wickedness and as part of a broader PKI plan to seize power. Within days, military propagandists had reshaped the name of the September 30 Movement to construct the acronym GESTAPU, with its connotations of the ruthless evil of the Gestapo. They concocted a story that the kidnapped generals had been tortured and sexually mutilated by communist women before being executed, and they portrayed the killings of October 1 as only a prelude to a planned nationwide purge of anticommunists by PKI members and supporters. In lurid accounts, PKI members were alleged to have dug countless holes so as to be ready to receive the bodies of their enemies. They were also accused of having been trained in the techniques of torture, mutilation, and murder.

The engagement of the PKI as an institution in the September 30 Movement was presented as fact rather than conjecture. Not only the party as a whole but also its political allies and affiliated organizations were portrayed as being guilty both of the crimes of the September 30 Movement and of conspiracy to commit further crimes on a far greater scale. At the same time, President Sukarno was portrayed as culpable for having tolerated the PKI within Guided Democracy. His effective powers were gradually circumscribed, and he was finally stripped of the presidency on March 12, 1967. General Suharto took over and installed a military-dominated, developmentoriented regime known as the New Order, which survived until 1998.

“In this context, the army began a purge of the PKI from Indonesian society. PKI offices were raided, ransacked, and burned. Communists and leftists were purged from government departments and private associations. Leftist organizations and leftist branches of larger organizations dissolved themselves. Within about two weeks of the suppression of the coup, the killing of communists began.

Victims of the 1965-66 Crackdown on Communists

The first victims were Communists. Next were perceived Communist sympathizers. It then escalated into a crack down and settling of scores against ethnic Chinese. Many of the victims were simply accused of being communists, an umbrella that included not only members of the country's Communist Party but also all those who opposed General Suharto's new military regime. Many of those that were killed were teachers and progressives and ethnic Chinese suspected of sympathizing with the Communists. At its height it was a settling of scores with anyone perceived as an enemy being a target.

Elizabeth Pisani wrote in her book “Indonesia Etc.” The leaders of the Communist crackdown unleashed “a tsunami of anti-P.K.I. propaganda, followed by revenge killings”...many ordinary Indonesians joined in with gusto.” Pankaj Mishra wrote in The New Yorker: The new rulers , Various groups—big landowners in Bali threatened by landless peasants, Dayak tribes resentful of ethnic Chinese—“used the great orgy of violence to settle different scores.” In Sumatra, “gangster organizations affiliated with business interests developed a special line in garroting communists who had tried to organize plantation workers.” The killings of 1965 and 1966 remain one of the great unpunished crimes of the twentieth century. The recent documentary “The Act of Killing” shows aging Indonesians eagerly boasting of their role in the exterminations. [Source: Pankaj Mishra, The New Yorker, August 4, 2014]

Cribb wrote: “It is important to note that Chinese Indonesians were not, for the most part, a significant group among the victims. Although Chinese have repeatedly been the target of violence in independent Indonesia, and although there are several reports of Chinese shops and houses being looted between 1965 and 1966, the vast majority of Chinese were not politically engaged and were expressly excluded from the massacres of communists in most regions. [Source: Robert Cribb, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

“Outside the capital, Jakarta, the army used local informants and captured party documents to identify its victims. At the highest level, however, the military also used information provided by United States intelligence sources to identify some thousands of people to be purged. Although the lists provided by the United States have not been released, it is likely that they included both known PKI leaders and others whom the American authorities believed to be agents of communist influence but who had no public affiliation with the party.

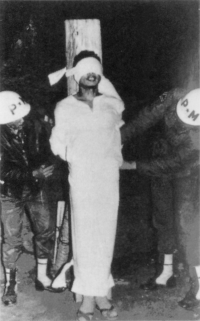

“The PKI leader Aidit, who went underground immediately after the failure of the coup, was captured and summarily executed, as were several other party leaders. Others, together with the military leaders of the September 30 Movement, were tried in special military tribunals and condemned to death. Most were executed soon afterward, but a few were held for longer periods, and the New Order periodically announced further executions. A few remained in jail in 1998 and were released by Suharto's successor, President B. J. Habibie.

Killing During the 1965-66 Crackdown on Communists

Robert Cribb wrote in the Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity:“Many analyses of the massacres have stressed the role of ordinary Indonesians in killing their communist neighbors. These accounts have pointed to the fact that anticommunism became a manifestation of older and deeper religious, ethnic, cultural, and class antagonisms. Political hostilities reinforced and were reinforced by more ancient enmities. Particularly in East Java, the initiative for some killing came from local Muslim leaders determined to extirpate an enemy whom they saw as infidel. Also important was the opaque political atmosphere of late Guided Democracy. Indonesia's economy was in serious decline, poverty was widespread, basic necessities were in short supply, semi-political criminal gangs made life insecure in many regions, and political debate was conducted with a bewildering mixture of venom and camaraderie. With official and public news sources entirely unreliable, people depended on rumor, which both sharpened antagonisms and exacerbated uncertainty. In these circumstances, the military's expert labeling of the PKI as the culprit in the events of October 1, and as the planner of still worse crimes, unleashed a wave of mass retaliation against the communists in which the common rhetoric was one of "them or us." [Source: Robert Cribb, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

“The killings peaked at different times in different regions. The majority of killings in Central Java were over by December 1965, while killings in Bali and in parts of Sumatra took place mainly in early 1966. Although the most intense of the killings were over by mid-March 1966, sporadic executions took place in most regions until at least 1970, and there were major military operations against alleged communist underground movements in West Kalimantan, Purwodadi (Central Java), and South Blitar (East Java) from 1967 to 1969.

“It is generally believed that the killings were most intense in Central and East Java, where they were fueled by religious tensions between santri (orthodox Muslims) and abangan (followers of a syncretic local Islam heavily influenced by pre-Islamic belief and practice). In Bali, class and religious tensions were strong; and in North Sumatra, the military managers of state-owned plantations had a special interest in destroying the power of the communist plantation workers' unions. There were pockets of intense killing, however, in other regions. The total number of victims to the end of 1969 is impossible to estimate reliably, but many scholars accept a figure of about 500,000. The highest estimate is 3,000,000.

Killers During the 1965-66 Crackdown on Communists

The killers were often members of paramilitary groups or death squads who carried out the executions with the approval of the military government and killed with impunity. The available evidence is meager and mostly anecdotal and suggests a complex picture. In some areas, clearly Muslim (in central and eastern Java, predominantly Nahdlatul Ulama) vigilantes began the murders spontaneously and, in a few places, even had to be reined in by army units. In others, army contacts either acquiesced to or encouraged such actions, and in a number of these there was a clear coordination of efforts. In what seems to have been a smaller number of places, army units alone were responsible. People participated in the killings, or looked the other way, for a wide variety of reasons, personal, community-related, and ideological. [Source: Library of Congress]

One participant in the killings in 1965 who was a member of a Muslim group told the Independent, “I didn’t kill them myself, but someone else did that. They were slaughtered like goats, thousands of them, and afterwards we threw them in a hole or in the sea. The Communists believed there was no God, they were the enemies of religion.”

Ann Hornaday wrote in the Washington Post, If the 2012 film “The Act of Killing” has a star, it’s Anwar Congo, a lean, gray-haired former death squad leader in North Sumatra, whom filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer met after interviewing dozens of perpetrators. For their first interview together, Congo took the filmmaker to a rooftop where he used to dispatch his victims. He uses a companion to demonstrate how he garroted people with a piece of wood and some wire. “At first, we beat them to death, but there was too much blood,” he said in the film. [Source: Ann Hornaday, Washington Post, July 25, 2013 ^]

Congo is rumored to have personally executed around 1,000 people. He turns out to be a bizarre protagonist, compelling and even engaging as a guide through Indonesia’s darkest chapters, repellent in his self-justification and lack of empathy, pathetic in his bravado. At one point on the roof, after he reenacts the murder, he begins to dance, explaining that he often went out partying after killing people. “When Anwar dances on the roof, I was shocked, I was outraged,” Oppenheimer says, recalling the moment. “I saw an allegory for impunity that would expose the nature of this regime just as I had been looking for on behalf of the survivors and the human rights community. But at the same time, I think there’s a stone in his shoe when he’s dancing the cha-cha-cha. He says he’s a good dancer because he was drinking, taking drugs, going out dancing to forget what he’s done. So I think he was shadowed by his past.” ^

Indonesian Military Involvement in the 1965-66 Killings

Cribb wrote; “Accounts of the killings that have emerged have indicated that the military played a key role in the killings in almost all regions. In broad terms, the massacres took place according to two patterns. In Central Java and parts of Flores and West Java, the killings took place as almost pure military operations. Army units, especially those of the elite para-commando regiment RPKAD, commanded by Sarwo Edhie, swept through district after district arresting communists on the basis of information provided by local authorities and executing them on the spot. [Source: Robert Cribb, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

In Central Java, some villages were wholly PKI and attempted to resist the military, but they were defeated and all or most villagers were massacred. In a few regions—notably Bali and East Java—civilian militias, drawn from religious groups (Muslim in East Java, Hindu in Bali, Christian in some other regions) but armed, trained, and authorized by the army, carried out raids themselves. Rarely did militias carry out massacres without explicit army approval and encouragement.

“More common was a pattern in which party members and other leftists were first detained. They were held in police stations, army camps, former schools or factories, and improvised camps. There they were interrogated for information and to obtain confessions before being taken away in batches to be executed, either by soldiers or by civilian militia recruited for the purpose. Most of the victims were killed with machetes or iron bars.

United States Involvement in the 1965-66 Violence in Indonesia

According to filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer the U.S. played a role in the killings. He told the New York Times: The United States provided the special radio system so the Army could coordinate the killings over the vast archipelago. A man named Bob Martens, who worked at the United States Embassy in Jakarta, was compiling lists of thousands of names of Indonesian public figures who might be opposed to the new regime and handed these lists over to the Indonesian government.” [Source: Adam Shatz, New York Times, July 9, 2015]

Declassified US documents released in 2017 revealed that Washington actively supported the Indonesian military’s killing in 1965-66, despite internal doubts about the official justification for the violence. About 30,000 pages of records from the US embassy in Jakarta show that American officials closely monitored the 1965–66 massacres and provided the Indonesian military with funding, equipment, and lists of communist officials at the height of the Cold War. [Source: e Financial Times, National Archives, 2017]

The documents also indicate that US officials possessed credible information contradicting Indonesian military claims that the murder of six army generals during a failed coup attempt in September 1965 had been ordered by the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). Instead, a US file from November 1965 suggested that the killings may have resulted from an internal power struggle—an “intra-government operation” aimed at removing a limited group of senior generals.

According to Bradley Simpson, a historian at Northwestern University who led the digitization of the files, the collection represents “the largest and most complete record of Indonesian politics at that time,” particularly because Indonesia has released few of its own official records from the period. John Roosa, an Indonesian history scholar at the University of British Columbia, noted that that it was striking that the US ambassador at the time, Marshall Green, was already aware in 1965 that the coup narrative had been exaggerated, yet continued to give it credence.

The files further reveal that US officials were informed that many confessions extracted from alleged communists had been fabricated by the Indonesian military. The declassified materials encompass most of the US embassy’s daily reporting between 1964 and 1968—a turbulent period during which Indonesia shifted from the authoritarian rule of its founding president, Sukarno, to Suharto’s military-led regime.

A 1967 embassy report stated that the United States had a “heavy stake in the outcome” of the new authoritarian government’s success.The files also provide further evidence of US involvement in shaping the allocation of Indonesia’s natural resources after the massacres. With the Indonesian economy in collapse during the transition, documents from 1967 show the Suharto government actively courting Western companies to return and invest in the country. The declassification effort was conducted jointly by the US government’s National Declassification Center and the National Security Archive, a nonprofit organization based at George Washington University in Washington, DC.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025