INDONESIA’S STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE

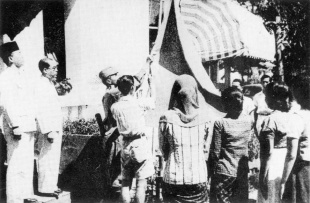

After three years of Japanese occupation during World War II, Indonesian nationalists led by Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta proclaimed the Republic of Indonesia on August 17, 1945—just days after Japan’s surrender. They established a provisional government and adopted a temporary constitution. The Dutch, refusing to accept the declaration, attempted to restore colonial rule. For the next four years, intermittent but often intense fighting took place, primarily in Java. Under growing international and UN pressure, the Netherlands agreed in November 1949 to transfer sovereignty to a federal Indonesian government. [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale, 2008; Clark E. Cunningham, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

For three years after World War II, the Netherlands attempted to reassert control over Indonesia. Fierce Indonesian resistance and mounting international pressure eventually forced the Dutch to concede. In 1949 they transferred sovereignty over the entire archipelago—except for West Papua. A new constitution came into effect in 1950, creating a formally unified nation-state.

The struggle that followed the proclamation of independence on August 17, 1945, and lasted until the Dutch recognition of Indonesian sovereignty on December 27, 1949, is generally referred to as Indonesia’s National Revolution. It remains the modern nation’s central event, and its world significance, although often underappreciated, is real. The National Revolution was the first and most immediately effective of the violent postwar struggles with European colonial powers, bringing political independence and, under the circumstances, a remarkable degree of unity to a diverse and far-flung nation of then 70 million people and geographically the most fragmented of the former colonies in Asia and Africa. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Furthermore, the Revolution accomplished this in the comparatively short period of slightly more than four years and at a human cost estimated at about 250,000 lives, far fewer than the several million suffered by India or Vietnam, for example. Representatives of the Republic of Indonesia were the first former colonial subjects to successfully use the United Nations (UN) and world opinion as decisive tools in achieving independence, and they carried on a sophisticated and often deft diplomacy to advance their cause. At home, it can certainly be argued that Republican forces fought a well-armed, determined European power to a standstill, and to the realization that further colonial mastery could not be achieved. Finally, although this point is much debated, it can be argued that the National Revolution generated irreversible currents of social and economic change marking the final disappearance of the colonial world and—for better or worse—serving as the foundation for crucial national developments over the next several generations. These were no mean achievements. *

RELATED ARTICLES:

INDONESIA DECLARES INDEPENDENCE IN 1945 AT THE END OF WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

INDONESIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE (1945-1949): POLICE ACTION, ATROCITIES, MASSACRES factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA OFFICIALLY ACHIEVES INDEPENDENCE factsanddetails.com

RISE OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF THE DUTCH EAST INDIES (1942-1945) factsanddetails.com

DIFFICULTY MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK IN INDONESIA IN THE 1950s factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO AS PRESIDENT: CHALLENGES, AUTHORITARIANISM, GUIDED DEMOCRACY factsanddetails.com

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNDER SUKARNO: NON-ALIGNMENT, ISOLATION, WAR WITH MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

Dutch Return to Indonesia After World War II

Sukarno and Hatta initially worked within Japan’s wartime propaganda framework, which denounced European colonial powers and the Western Allies. Yet this period also fueled nationalist sentiment among Indonesians, especially the youth. Following Japan’s defeat, demands for independence surged. Sukarno became president, Hatta vice president, and Egypt became the first country to recognize the new republic. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

In general, the Dutch view in late 1945 had been that the Republic of Indonesia was a sham, controlled largely by those who had collaborated with the Japanese, with no legitimacy whatsoever. A year later, this outlook had been modified somewhat, but only to concede that nationalist sentiment was more widespread than they had at first allowed; the complaint grew that, whatever its nature, the Republic could not control its violent supporters (especially “pemuda”and communists), making it unfit to rule. The newly formed United Nations formed a commission to settle the dispute. In 1946, the British left and the Dutch arrived and the Dutch and Indonesians signed a agreement calling for the gradual hangover transition from colonialism to self rule but fighting continued for three more years until 1949. [Source: Library of Congress *]

According to Lonely Planet: “The Dutch dream of easy reoccupation was shattered, while the British were keen to extricate themselves from military action and broker a peace agreement. The last British troops left in November 1946, by which time 55,000 Dutch troops had landed in Java. Indonesian Republican officials were imprisoned, and bombing raids on Palembang and Medan in Sumatra prepared the way for the Dutch occupation of these cities. In southern Sulawesi, Dutch Captain Westerling was accused of pacifying the region – by murdering 40,000 Indonesians in a few weeks. Elsewhere, the Dutch were attempting to form puppet states among the more amenable ethnic groups.” [Source: Lonely Planet]

Linggadjati Agreement

The Dutch, realizing their weak position during the year following the Japanese surrender, were initially disposed to negotiate with the republic for some form of commonwealth relationship between the archipelago and the Netherlands. The negotiations resulted in the British-brokered Linggajati Agreement, initialled on November 12, 1946. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The Linggadjati Agreement acknowledged Republican control on Sumatra, Java, and Madura, as well as a federation of states under the Dutch crown in the eastern archipelago. The agreement also called for the formation, by January 1, 1949, of a federated state comprising the entire former Netherlands Indies, a Netherlands– Indonesian Union, or the so-called United States of Indonesia, which was also to be part of a larger commonwealth (including Suriname and the Dutch Antilles) under the Dutch crown. *

The agreement provided for Dutch recognition of republican rule on Java and Sumatra, and the Netherlands-Indonesian Union under the Dutch crown (consisting of the Netherlands, the republic, and the eastern archipelago). The archipelago was to have a loose federal arrangement, the Republic of the United States of Indonesia (RUSI), comprising the republic (on Java and Sumatra), southern Kalimantan, and the "Great East" consisting of Sulawesi, Maluku, the Lesser Sunda Islands, and West New Guinea. The KNIP did not ratify the agreement until March 1947, and neither the republic nor the Dutch were happy with it. The agreement was signed on May 25, 1947. *

The Linggajati Agreement was not popular on either side. Among many Indonesian nationalists of various political stripes, the agreement was seen as a capitulation by the Republican government. “Pemuda”of both left and right championed the idea of “100 percent Independence” (“Seratus Persen Merdeka”), and the communist-nationalist Tan Malaka coupled this with accusations that both Sukarno and Hatta had betrayed the nation once with their collaboration with the Japanese, and were doing so once again by compromising with the Dutch. Tan Malaka formed a united front known as the Struggle Coalition (Persatuan Perjuangan), which used the idea of total opposition to the Dutch to gather support for his own political agenda.

Renville Agreement

On July 21, 1947, less than two months after the KNIP had, following bitter debate and maneuvering, approved the agreement, Dutch forces launched what they euphemistically called a “police action” against the Republic, claiming it had violated or allowed violations of the Linggajati Agreement. Republican officials were imprisoned in Java and Kalimantan; the Dutch occupied Medan and Palembang in Sumatra after a series of bombings there. In south Sulawesi a Captain Westerling was accused of pacifying the region by murdering 40,000 Indonesians in a few weeks. The Dutch retook Jakarta and the republicans set up their government in Yogyakarta.

Dutch troops drove the republicans out of Sumatra and East and West Java, confining them to the Yogyakarta region of Central Java. They secured most of the large cities and valuable plantation areas of Sumatra and Java and arbitrarily established boundaries between their territories and the Republic, known as the Van Mook Line, after Lieutenant Governor General H. J. van Mook. The Republican military, the Indonesian National Army (TNI), and its affiliated militia (“laskar”) were humiliated, and yet greater criticism of the government arose, now even from within the military itself and from Muslim leaders. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The international reaction to the police action was against the Dutch. The United Nations Security Council established a Good Offices Committee to sponsor further negotiations. This action led to the Renville Agreement (named for the United States Navy ship on which the negotiations were held), which was ratified by both sides on January 17, 1948. It recognized temporary Dutch control of areas taken by the police action but provided for referendums in occupied areas on their political future. *

The Republic had from the start of the Revolution pursued a vigorous if informal diplomacy to win other powers to its side, efforts that now bore fruit. The UN listened sympathetically to Prime Minister Syahrir’s account of the situation in mid-August 1947, and a month later announced the establishment of a Committee of Good Offices, with members from Australia, Belgium, and the United States, to assist in reaching a settlement. The Renville Agreement, proved even less popular in the Republic than its predecessor, as it appeared to accept both the Van Mook Line, which in fact left numbers of TNI troops inside Dutch-claimed territories, requiring their withdrawal, and the Dutch notion of a federation rather than a unitary state pending eventual plebiscites. Republican leaders reluctantly signed it because they believed it was essential to retaining international goodwill, especially that of the United States. In the long run, they may have been correct, but the short-term costs were enormous.

Indonesian Republic Struggles to Set Up a Government

In the meantime a Republican government had been formed in Jakarta with Sukarno as President and Hatta as Vice President. In November 1945, through the efforts of Sultan Syahrir, a Sumatran socialist, the new republic was given a parliamentary form of government. Syahrir, who had refused to cooperate with the wartime Japanese regime and had campaigned hard against retaining occupation-era institutions, such as Peta, was appointed the first prime minister and headed three short-lived cabinets until he was ousted by his deputy, Amir Syarifuddin, in June 1947. The Republican government tried to maintain calm while the pemuda advocated armed struggle against both the Dutch and the Republican government. and saw the old leadership as prevaricating and betraying the revolution.

Internally the Republic was threatening to disintegrate. Public confidence in the Republic began to erode because of the worsening economic situation, caused in part by the Dutch blockade of sea trade and seizure of principal revenue-producing plantation regions, as well as by a confused monetary situation in which Dutch, Republican, and sometimes locally issued currencies competed. Conflict became more frequent between the TNI and “laskar”and among “laskar”, as they competed for territory and resources or argued over tactics and political affiliation. The KNIP initiated a reorganization and rationalization program in December 1947, seeking to reduce regular and irregular armed forces drastically in order the better to supply, train, and control them.

At this time outbreaks of violence were occurring across the country, and Sukarno and Hatta were outmaneuvred in the Republican government. Sultan Syahrir, became prime minister and, as the Dutch assumed control in Jakarta, the Republicans moved their capital to Yogyakarta. Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX, who was to become Yogyakarta’s most revered and able sultan, played a leading role in the revolution. [Source: Lonely Planet]

Political Chaos in Indonesia as the Republican Government Weakens

The battle for independence wavered between warfare and diplomacy. The Linggarjati Agreement of November 1946, in which the Dutch recognised the Republican government and both sides agreed to work towards an Indonesian federation under a Dutch commonwealth, was swept aside as war escalated. Increasingly divisions were opening up and violence was occurring between Indonesian groups and by Indonesian groups beyond the control of the Republican Indonesian government.

According to Lonely Planet: During these uncertain times, the main forces in Indonesian politics regrouped: the communist PKI, Sukarno’s PNI, and the Islamic parties of Masyumi and Nahdatul Ulama. The army also emerged as a force, though it was split by many factions. The Republicans were far from united, and in Java civil war threatened to erupt when in 1948 the PKI staged rebellions in Surakarta (Solo) and Madiun. In a tense threat to the revolution, Sukarno galvanised opposition to the communists, who were massacred by army forces. [Source: Lonely Planet]

The Renville Agreement marked the low point of republican fortunes. To patriots as well as those with other motives, this move seemed no better than treason, and the result was chaos. In addition, tensions mounted rapidly and at all levels between Muslims and both the government and leftist forces. Local clashes were reported in eastern and western Java after early 1948, but the most immediate challenge to the Republic was the movement led by S. M. Kartosuwiryo (1905–62), an Islamic mystic and a foster son of H. U. S. Cokroaminoto, who had supported the 1928 Youth Pledge and “pemuda”nationalists in 1945 but later felt betrayed by the Renville Agreement and took up arms against the Republic, with himself at the head of an Islamic Army of Indonesia (TII).

Kartosuwirjo, with the support of kyai and others, established a breakaway regime in the Garut-Tasikmalaya region of western Java in May 1948. Kartosuwiryo declared a separately administrated area, Darul Islam (Abode of Islam), which in 1949 he called the Islamic State of Indonesia (NII, Negara Islam Indonesia). Darul Islam (from the Arabic, dar-al-Islam, house or country of Islam) was a political movement committed to the establishment of a Muslim theocracy. Kartosuwirjo and his followers stirred the cauldron of local unrest in West Java until he was captured and executed in 1962. *

Devout Muslim fighters were among the bravest fighters against both the Dutch and the Japanese. Mystical suicide warriors were enlisted in the fight against the Dutch. On man told the Independent. “My uncle had this power. He once fired a catapult at a Dutch plane that was flying overhead. It was just a small stone, but the plane crashed in flames. the fighters had only bamboo spears but they pointed them at Dutch soldiers and they would fall down.”

Rise of the Indonesian Communists

Most serious of all, however, was the upheaval precipitated in September 1948 by the return from the Soviet Union of the prewar communist leader Muso (1897–1948), and his efforts to propel the PKI to a position of leadership in the Revolution. Musso, a leader of the PKI from the insurgency of the 1920s, and Trotskyite forces led by Tan Malaka bridled at what they saw as the republic's unforgivable compromise of national independence. They berated the Sukarno–Hatta leadership for compromising with the Dutch and called for, among other things, an agrarian revolution.

Local clashes between republican armed forces and the PKI broke out in September 1948 in Surakarta in central Java. The communists then retreated to Madiun in East Java and called on the masses to overthrow the government. On September 18, 1948 PKI-affiliated “laskar”took over the eastern Java city of Madiun, where they murdered civil and military figures, announced a National Front government, and asked for popular support. The Republic responded immediately with a dramatic radio speech by Sukarno calling on the masses to choose between him—and the nation—or Muso. The TNI, especially western Java’s Siliwangi Division under Abdul Haris Nasution (1918–2001), mounted a brutally successful campaign against the rebel forces. Musso was killed, and Tan Malaka was captured and executed by republic troops in February 1949. All told approximately 30,000 people lost their lives on both sides in the conflict.

An important international implication of the Madiun insurrection was that the United States now saw the republicans as anticommunist — rather than "red" as the Dutch claimed — and began to pressure the Netherlands to accommodate independence demands. Even though the republican government demonstrated it could crush the PKI at will and many PKI members abandoned the party, the PKI painfully rebuilt itself and became a political force to be reckoned with in the 1950s. The Madiun Affair remains controversial today, but its outcome strengthened the Republican government’s efforts to control those who opposed it and changed the way in which Sukarno and the Republic were seen overseas, especially in the United States, where in the Cold War paradigm Indonesia now appeared as an anticommunist power. In the months after Madiun, the Dutch grew increasingly frustrated. Their negative portrayal of the Republic had lost international credibility, and on the ground their military position was deteriorating. Intelligence indicated as many as 12,000 Indonesian troops operating inside the Van Mook Line. *

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025