DIFFICULTY MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK IN INDONESIA

On December 27 1949, shortly after hostilities with the Dutch ended, the Dutch formerly granted independence to Indonesia. Indonesia adopted a new constitution that provided for a parliamentary system of government, in which the executive branch would be chosen by and accountable to Parliament. Before and after the country's first nationwide election in 1955, parliament was divided among many political parties, making stable governmental coalitions difficult to achieve. The role of Islam in Indonesia became a divisive issue. Sukarno defended a secular state based on the five principles of the state philosophy, or Pancasil, codified in the 1945 constitution: monotheism, [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale, 2008]

Independence had brought with it expectations of a modern political framework for the nation. The Republic’s founders had rejected colonialism, of course, and monarchy, settling on a vaguely defined democracy that leaned heavily on presidential authority. The constitution of the RIS and a third (provisional) constitution adopted in 1950 by the unitary state called for a prime ministerial, multiparty, parliamentary democracy and free elections. When voters went to the polls in September 1955, there was considerable hope that such a system would provide solutions to the political divisiveness that, freed from the limitations of the common anticolonial struggle, had begun to spread well beyond the mostly urbanized educated elite. [Source: Library of Congress *]

There was little in the diverse cultures of Indonesia or their historical experience to prepare Indonesians for democracy. The Dutch had done practically nothing to prepare the colony for selfgovernment . The Japanese had espoused an authoritarian state, based on collectivist and ethnic nationalist ideas, and these ideas found a ready reception in leaders like Sukarno. Sukarno also was an advocate of adopting Bahasa Indonesia as the national language. Outside of a small number of urban areas, the people still lived in a cultural milieu that stressed status hierarchies and obedience to authority, a pattern that was most widespread in Java but not limited to it. Powerful Islamic and leftist currents were also far from democratic. Conditions were exacerbated by economic disruption, the wartime and postwar devastation of vital industries, unabated population growth, and resultant food shortages. By the mid-1950s, the country's prospects for democratization were indeed grim. *

Democracy has had a hard time working because Indonesia is divided by so many different groups and factions. Regional differences, different custom of different ethnic groups, the impact of Christianity and Marxism and fear of being dominated by Java all prevented a sense of unity from being generated to accomplish anything for the common good. Fiercely competitive and independent political parties were created, each fighting for its own turf and together making it impossible for stable governments to be formed. Coalition governments came and went. There were 17 governments between 1945 and 1958. They result was often paralysis and stagnation.

Throughout the 1950s, separatist movements came and went in Sumatra, Sulawesi, the Moluccas and other places, and radical Muslims and Communist stirred up unrest. The militant Islamic group Islamic Domain declared an Islamic State of Indonesia and carried out a guerilla campaign in western Java from 1949 to 1962.

RELATED ARTICLES:

INDONESIA DECLARES INDEPENDENCE IN 1945 AT THE END OF WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA’S NATIONAL REVOLUTION: THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE 1945-1949 factsanddetails.com

INDONESIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE (1945-1949): POLICE ACTION, ATROCITIES, MASSACRES factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA OFFICIALLY ACHIEVES INDEPENDENCE factsanddetails.com

RISE OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF THE DUTCH EAST INDIES (1942-1945) factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO AS PRESIDENT: CHALLENGES, AUTHORITARIANISM, GUIDED DEMOCRACY factsanddetails.com

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNDER SUKARNO: NON-ALIGNMENT, ISOLATION, WAR WITH MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

Indonesia’s First Election in 1955

The 1955 election was Indonesia’s first ever election. The election was initially planned for October 1945 but due to the nation’s instability was not finally executed until after Indonesia’s declaration of independence. No limit was placed on the number of parties who could run, leading to a total of 80 parties, organizations and individuals registering as contenders. Every citizen had the right to vote, including the military and police corps. There were two election periods. The September election period was to elect members of the House of Representatives (DPR) while the December election period was to elect members of the “Konstituante,” a special board set up to draft a new constitution.

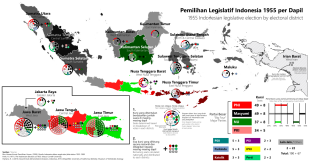

Independent Indonesia's first general election took place on September 29, 1955. It involved a universal adult franchise, and almost 38 million people participated. Sukarno's PNI won a slim plurality with the largest number of votes, 22.3 percent, and fifty-seven seats in the House of Representatives. Masyumi, which operated as a political party during the parliamentary era, won 20.9 percent of the vote and fifty-seven seats; the Nahdatul Ulama, which had split off from Masyumi in 1952, won 18.4 percent of the vote and forty-five seats. The PKI made an impressive showing, obtaining 16.4 percent of the vote and thirty-nine seats, a result that apparently reflected its appeal among the poorest people; the Indonesian Socialist Party (PSI) won 2 percent of the vote and five seats. [Source: Library of Congress *]

However, the national elections proved disappointing. The four major winners among the 28 parties obtaining parliamentary seats were the secular nationalist PNI (22 percent, with 86 percent of that from Java), the modernist Muslim Masyumi (21 percent, with 51 percent from Java), the traditional Muslim Nahdlatul Ulama (18 percent, with 86 percent from Java), and the PKI (16 percent, with 89 percent from Java). After the PKI, the next most successful party, the Indonesian Islamic Union Party (PSII), received less than 3 percent of the vote, and 18 of 28 parties received less than 1 percent of the vote. Both Nahdlatul Ulama and the PKI, which had especially strong followings in central and eastern Java, dramatically increased their representation compared with what they had held in the provisional parliament (8 to 45 seats, and 17 to 39 seats, respectively). In eastern Java, the vote was split almost evenly among the PNI, PKI, and Nahdlatul Ulama. The elections thus exposed and sharpened existing divides between Java and the other islands, raising fears of domination by Jakarta, and between the rapidly rising PKI and, particularly, Muslim parties, raising fears of communist (interpreted as antireligious) and populist ascendancy. *

To make matters worse, there was a general perception that in the 30-month run-up to the elections, the political process had polarized villages as parties sought votes. There were many reports of villagers being pressured and even threatened to vote for one or another party, and of clashes between Muslim and communist adherents. More-educated voters tended to take hardened ideological positions. On the eve of the elections, Sukarno had declared that anyone who “tried to put obstacles in the way of holding them ... is a traitor to the Revolution.” Barely six months later, he was urging the new parliament to avoid “50 percent + 1 democracy,” and in October spoke of “burying” the political parties and of his desire to see Guided Democracy (demokrasi terpimpin, a term Sukarno had been using since 1954) in Indonesia. *

In December 1955, the long-awaited Constituent Assembly was elected to draft a constitution to replace the provisional constitution of 1950. The membership was largely the same as the DPR. In On March 1956 a parliament consisting of 27 political parties and one individual was formed from the 1955 election winners. The top parties, taking 77 of the parliament’s total seats, were Islamic Masyumi Party, Indonesian National Party (PNI), Nadhlatul Ulama and Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). The PNI, PKI, and Nahdatul Ulama were strongest among Javanese voters, whereas Masyumi gained its major support from voters outside Java. No single group, or stable coalition of groups, was strong enough to provide national leadership, however. The assembly became deadlocked over issues such as the Pancasila as the state ideology. The result was chronic instability, reflected in six cabinet changes between 1950 and 1957, that eroded the foundations of the parliamentary system. The assembly was dissolved in 1959.*

In the eastern archipelago and Sumatra, military officers established their own satrapies, often reaping large profits from smuggling. Nasution, reappointed and working in cooperation with Sukarno, issued an order in 1955 transferring these officers out of their localities. The result was an attempted coup d'état launched during October-November 1956. Although the coup failed, the instigators went underground, and military officers in some parts of Sumatra seized control of civilian governments in defiance of Jakarta. In March 1957, Lieutenant Colonel H.N.V. Sumual, commander of the East Indonesia Military Region based in Ujungpandang, issued a Universal Struggle Charter (Permesta) calling for "completion of the Indonesian revolution." Moreover, the Darul Islam movement, originally based in West Java, had spread to Aceh and southern Sulawesi. The Republic of Indonesia was falling apart, testimony in the eyes of Sukarno and Nasution that the parliamentary system was unworkable. *

Economic Pressures in Newly-Independent Indonesia

In the early 1950s, Indonesia’s economy experienced a boomlet, principally as a result of Korean War (1950–53) trade, especially in oil and rubber; taxes on this trade supplied nearly 70 percent of the government’s revenues. Between 1950 and 1955, the gross national product (GNP) is thought to have grown at an annual rate of about 5.5 percent, and it increased 23 percent between 1953—when real GDP again reached the 1938 level—and 1957. In retrospect, economists seem agreed that, against heavy odds, the immediate postcolonial economy was not hopeless. Nevertheless, what most Indonesians saw and felt did not seem like economic progress at all: wages rose, but prices rose faster, and the growing ranks of urban workers and government employees were especially vulnerable to the resulting squeeze. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The government also was squeezed between falling trade-tax revenues and rising expenses, especially those required to support a bureaucracy that nearly doubled in size between 1950 and 1960. Infrastructure, badly needing rehabilitation, was neglected, adversely affecting production and trade. Corruption and crime spread. In 1956 rice made up 13 percent of Indonesia’s imports, compared to self-sufficiency in 1938; by 1960 only 10 percent of the national income derived from manufacturing, compared to 12 percent in 1938. In economists’ terms this was “structural regression,” but in everyday experience it meant that the economy was not modernizing, and it was increasingly unable to provide for a population estimated to have grown from 77 million in 1950 to 97 million a decade later. *

In order to solve these problems, the government at first embarked on plans—many of which had been initiated by the Dutch in the late 1930s and again in territories they held in the immediate postwar years—for large- and small-scale industrialization, import-substitution manufacturing, and private and foreign capitalization. It was not long, however, before policies more familiar to the prewar generation of nationalists, now firmly in power, took precedence. These were already visible in the Benteng (Fortress) Program (1950–57), one aspect of which was discrimination against ethnic Chinese and Dutch entrepreneurs in order to foster an indigenous class of businessmen. *

The Benteng Program failed, leading instead to more corruption, but the call for “Indonesianization” of the economy was very strong. Policies increasingly favored a high degree of centralization, government development of state enterprises, discouragement of foreign investment, and, at least for a time, the encouragement of village cooperatives, all of which harkened back to provisions of the 1945 constitution and had been pursued in a limited fashion during the National Revolution. Gradual nationalization of some Dutch enterprises, the central bank, the rail and postal services, and air and sea transport firms began in the early 1950s, but the pace quickened after 1955 because of the continuing dispute over West New Guinea, control of which had not been settled in 1949. In 1957 and 1958, nearly 1,000 Dutch companies were nationalized and seized by the armed forces or, less frequently, by labor groups; in a corresponding exodus, nearly 90 percent of remaining Dutch citizens voluntarily repatriated. A year later, a decree banning “foreign nationals” resulted in 100,000 Chinese repatriating to mainland China. A victory from a nationalist perspective, this was from an economic standpoint—not least of all because Indonesia lacked capital and credit, as well as modern management and entrepreneurial skills—a setback from which recovery would be difficult. *

Political Divisiveness in Newly-Independent Indonesia

According to Lonely Planet: “In the first years of independence, the threat of external attacks by the Dutch helped keep the nationalists united. However, with the Dutch gone, divisions in Indonesian society began to appear. Sukarno had tried to hammer out the principles of Indonesian unity in his Pancasila speech of 1945 but while these, as he said, may have been ‘the highest common factor and the lowest common multiple of Indonesian thought’, divisions could not be swept away by a single speech. Regional differences in customs, morals, traditions and religion, the impact of Christianity and Marxism, and fears of political domination by the Javanese all contributed to disunity. [Source: Lonely Planet ++]

“Various separatist movements battled the new republic. They included the militant Darul Islam (Islamic Domain), which proclaimed an Islamic State of Indonesia and waged guerrilla warfare in West Java and south Sula―wesi from 1948 to 1962. In Maluku, Ambonese members of the former Royal Dutch Indies Army tried to establish an independent republic. Against this background lay the sorry state of the conflict-battered economy and divisions in the leadership. The population was increasing but food production was low and the export economy was damaged, as many plantations had been destroyed during the war. Illiteracy was high and there was a dearth of skilled workers. Inflation was chronic and smuggling was costing the government badly needed foreign currency. ++

On top of this, political parties proliferated and there were continuous deals brokered between parties for a share of cabinet seats. This resulted in a rapid turnover of coalition governments: 17 cabinets over 13 years. Frequently postponed national elections were finally held in 1955 and the PNI – regarded as Sukarno’s party – narrowly topped the poll. There was a dramatic increase in support for the PKI but no party managed more than a quarter of the votes, and so short-lived coalitions continued. ++

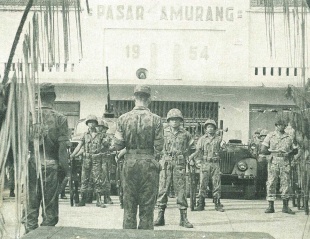

Military Involvement and Rebellion

Into this deteriorating situation, the military increasingly inserted itself. During the Revolution, the armed forces had developed a strong distrust for—indeed, taken up arms against—both communist and Muslim movements that had opposed the central government. The military had also itself exhibited a resistance to control by the central government and, especially after the second “police action” and subsequent gerilya, a high level of disapproval of civilian politics and politicians in general. Further, the armed forces had never been united, even on these issues, which made for extremely complex struggles in which military leaders often ended up opposing each other. These tensions surfaced, for example, when a dispute over demobilization plans resulted in a dangerous confrontation between some army commanders and parliament in Jakarta on October 17, 1952. [Source: Library of Congress *]

In 1956, in reaction to Jakarta’s continued efforts to curb TNI-supported smuggling of oil, rubber, copra, and other export products, commanders in Sumatra and Sulawesi bolted from both government and central TNI control, arguing that their regions were producing more than their share of exports but receiving too little in return from the central government. The army was also growing increasingly concerned about the PKI’s rise to power. PKI membership had leapt from about 100,000 in 1952 to a purported 1 million at the end of 1955, and, more successfully than any other party, it had cultivated village interests with community projects and support, particularly on Java. At the end of 1956, a dissident TNI commander, Zulkifli Lubis (1923–94?), wrote that Sukarno himself, recently returned from a visit to the People’s Republic of China, had chosen that country as a political model. On February 21, 1957, Sukarno, supported by army chief Nasution, proposed instituting a system of Guided Democracy, which he now conceptualized as based on a politics of mutual cooperation (gotong royong) and deliberation with consensus (musyawarah mufakat) among functional groups (golongan karya) rather than political parties, which he believed was more in keeping with the national character. This seemed to many dissidents to signal both the end of any hope of improving regional prospects, and the beginning of, at the very least, a communist-tinted authoritarian rule. *

In early March 1957, the TNI commander of East Indonesia announced Universal Struggle (Permesta) and declared martial law in his region, claiming a goal of completing the National Revolution. Nasution then proposed that Sukarno declare martial law for all of Indonesia, which he did on March 14. In the repression of suspected dissidents in Java, especially of Masyumi leaders, who had vigorously opposed the institution of Guided Democracy, a number of these prominent figures fled to Sumatra. They included the former prime minister from 1950–51, Mohammad Natsir (1908–93); former central bank president Syafruddin Prawiranegara (1911–89); and former minister of finance Sumitro Joyohadikusumo (1917–2001), who joined army dissidents in Sumatra, eventually declaring, in mid-February 1958, the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PRRI). They were immediately joined by the Permesta rebels, and also attracted the clandestine support of the United States (revealed in May when an American pilot was shot down during a rebel attack on government forces). The central government acted swiftly, and TNI forces broke the rebellion in no more than two months, although sporadic guerrilla fighting continued until the early 1960s. *

It has been pointed out many times that the PRRI did not represent a true separatist movement and sought instead what today would be termed “regime change.” Be that as it may, the revolt was a watershed of some importance. Official figures estimate that at least 30,000 people lost their lives in the fighting, and Indonesian political life, far from being improved and stabilized as so fondly hoped, was instead gripped by regional, religious, and ideological turmoil and bitterness made worse by economic decay.

Moluccan Independence Movement

After the end of World War II, many Christians remained loyal to the Dutch and fought on their side against Indonesia nationalists. After Indonesia achieved independence, the Christians wanted to make the Moluccas independent of Indonesia because they worried they wouldn’t fare very well in a nation that was 90 percent Muslims.

In Maluka, Dutch loyalists tried to establish an independent republic. In the 1950, the Republic of South Moluccas (RMS) was declared in Ambon. Within a few months Indonesian troops retook Bury and Seram but resistance endured in Ambon until the leader of the movement fled to the jungles of Seram, where the group held out until the mid 1960s.

Christians with ties to the Dutch colonial administration battled with Indonesian troops in an effort to secede but their effort failed. Out of fear or reprisals from the Indonesian government, a group of 12,000 diehard Christian nationalists were removed from the Moluccas by the Dutch and placed in a converted concentration camp in Holland with what they thought was a promise that they would be returned to an independent Moluccas. That never happened and their offspring still remain in Holland, feeling betrayed and resisting all attempts to be re-assimilated.

North Sulawesi was also the site of a determined separatist movement. The people that inhabit this area are called Minahasa which refers to a confederation of tribes most which are Christians. They were very close with the Dutch and tried to establish an independent state in 1957, resulting in the bombing of Manado and Indonesian army invasion.

According to a March 5, 1957 U.S. government report entitled “The Situation in Indonesia” read: 1. On March 2 the Commander of Territory VII in Eastern Indonesia2 proclaimed martial law, designated military governors for the four provinces within his command (Celebes, Moluccas, Lesser Sundas and West New Guinea), and presented an ultimatum to the Djakarta government. In addition to greater regional autonomy and the retention of seventy percent of the revenues of the provinces, which would be used for economic development within his territory, he made additional demands with respect to governmental changes proposed earlier by President Sukarno. On March 5 he demanded that Prime Minister Ali resign and stated that Communists would not be tolerated in the government. [Source: Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955–1957m Volume XXII, Southeast Asia, Document 216. Report by the Intelligence Advisory Committee]

These events in Eastern Indonesia are the latest in a series of bloodless insurgencies which have seen army commanders, apparently supported by civilian elements, take over the North, Central and South Sumatra provinces in defiance of the Djakarta government. They have all demanded a greater degree of autonomy, but have given no indication of an intent to quit the Republic. Some have declared a loyalty to President Sukarno but have made it clear that they oppose the present cabinet. Earlier, in the period from August to November 1956, coups planned by Army elements in West Java apparently were thwarted by the government.

Developments in Eastern Indonesia and Sumatra are all symptomatic of increasing unrest in the Indonesian Army and of growing regionalism in areas outside Java. Poor living conditions for the troops, outmoded equipment, and a cumbersome organization have drawn the criticism of some Army leaders. Repeated appeals to the government for funds to carry out improvements in the Army have met with little effective response, while the incidence of corruption in high places has destroyed the faith of many Army leaders that conditions would improve.

At the same time Army commanders in the areas outside Java are influenced by growing pressure from the population for increased local control of government and finances. This pressure has resulted from the failure of the central government to bring about improvements in communications, school facilities and living standards—all of which had been among the objectives of the revolution against the Dutch. The feeling that the government administration is dominated by the Javanese, and that the outlying provinces are not receiving economic benefits commensurate with their contributions to the government’s revenues have added to regional sentiment. In acting as they did, Army leaders have not only served their own interests but appear to have expressed the views of a substantial part of the Indonesian people.

Partly in answer to growing disaffection and perhaps influenced by impressions gathered during a visit to the Soviet Union and Communist China during the fall of 1956, President Sukarno made public on February 21 his “concept” of a new organizational form for Indonesian democracy. He would establish a national council representative of all parties in the parliament but augmented by delegates of functional sectors of society, including veterans, laborers, and the armed forces. The council would give “advice,” apparently mandatory, to Parliament and to the cabinet, which again would be representative of all elements in Parliament. In outlining his plan, Sukarno, obviously harking back to the nationalist unity which prevailed during the independence struggle, held that opposition was the key to the failure of parliamentary democracy in Indonesia and that elimination of an opposition by inclusion of all elements in the government would ensure its success.

Because the Indonesian Communist Party would have official status in the government for the first time since Indonesia became independent in 1949, Sukarno’s plan has had a mixed reception. It has also been pointed out that the proposals offer little hope of dealing with the problems of growing regional feeling. Only two of the major parties support Sukarno’s proposal, the Nationalist Party, albeit reluctantly, and the Communists. Impressed by the reluctance of the other parties to support him, Sukarno has announced that he would study counterproposals, thus holding out the hope of eventual adjustment or compromise.

Indonesian Worldview and Foreign Policy in the 1950s

Indonesian nationalists had the strong expectation that independence would also bring Indonesia international recognition and a place in the family of nations. Admission to the UN in September 1950 was a first step, and Indonesia quickly adopted an “independent and active” foreign policy, first articulated in 1948 by then Vice President Mohammad Hatta, who wished to steer a course between the Cold War powers but to do so in a way that was not merely “neutral.” The first fruit of this outlook was the Asia–Africa Conference held in Bandung, Jawa Barat Province, in April 1955. This gathering of 29 new nations sought to avoid entanglement in the Cold War and to promote peace and cooperation; to many it represented the sudden coming of age of the formerly colonized world. It is generally considered the beginning of the Nonaligned Movement, although the movement itself was not formalized until 1961.

Sukarno was in his element at Bandung, speaking eloquently about ex-colonial peoples “awakening from slumber” and proposing—true to his homegrown pattern—an ideology of neither capitalism nor communism but one that merged the nationalism, religion, and humanism of Asia and Africa. As at home, however, this grand attempt at balance and synthesis did not hold. The failure of Indonesian nonalignment policies during the Cold War came about in part because of the unwillingness of the superpowers, perhaps especially the United States, to view the decolonized world in anything but friend-or-foe terms. Sukarno’s willingness to use Cold War rivalries for what he viewed as Indonesia’s national interests, which was not precisely in the spirit of Bandung, also led to the abandonment of neutrality. *

In the ongoing dispute with the Dutch over West New Guinea, for example, Sukarno had tentatively used the support of the Soviet Union and China, and of the PKI at home, to encourage the United States to pressure the Dutch to abandon the territory, implicitly in hopes of forestalling an Indonesian slide toward the communist bloc. A U.S.- and UN-brokered agreement turned over control to Indonesia in May 1963, which was confirmed in the much-disputed Act of Free Choice in 1969. In the issues that arose over the formation of Malaysia—an idea that had surfaced in 1961 as a solution to British decolonization problems involving Malaya, Singapore, and British Borneo, but which appeared in Jakarta’s eyes to be a neocolonial plot against the republic and its ongoing revolution—Sukarno at first merely meddled and then, when the new state was formed in 1963, declared Confrontation, or Konfrontasi as it was called in Indonesian, a step that led the nation to the brink of war. Confrontation had support from both China and the Soviet Union (by then themselves estranged) as well as the PKI but was opposed by Britain and the United States, and, surreptitiously, by elements of ABRI. Sukarno was now faced with increasing isolation from the Western powers, and the deepening unpredictability of interlocking power struggles on both international and domestic fronts. This was not the “joining the world” for which most nationalists had hoped.

Political Paralysis in Post-Independence Indonesia

Symbolic of the paralysis that gripped political life at the time, the Constituent Assembly (Konstituante), which had been elected in late 1955 and began meeting a year later, by mid-1959 had failed to reach agreement on major issues that had troubled the BPUPK and PPKI a decade earlier: whether the form of the state should be federative or unitary and whether the state should be based on Islam or Pancasila. In May, Jakarta granted the northern Sumatra province of Aceh semiautonomous status (and thus the freedom to establish government by Islamic law) as the price of at last ending the struggle there with Darul Islam forces. The way seemed open for a dissolution of the unitary state. Sukarno’s response on July 5, 1959, was unilaterally to dismiss the Constituent Assembly and to declare that the nation would return to the constitution of August 18, 1945, pointedly without the Jakarta Charter and its Islamic provisions. Illegal although it may have been, this was not an entirely unwelcome move. Many, although by no means all, Indonesians believed that their nation had lost its way, and a return to first principles and sentiments—now rather romantically misimagined—sounded in many ways attractive. What followed, however, was the rapid development of an authoritarian state in which tensions were not reduced but greatly exacerbated. [Source: Library of Congress *]

On August 17, 1959, Sukarno attempted to give Guided Democracy some precise content by announcing his Political Manifesto (Manipol), which included the ideas of “returning to the rails of the Revolution” and “retooling” in the name of unity and progress. Manipol was supplemented with the announcement of a kind of second Pancasila describing the foundations of the new state: the 1945 constitution, Indonesian Socialism, Guided Democracy, Guided Economy, and Indonesian Identity, expressed in the acronym USDEK. These two formulations were followed in mid- 1960 with a third, known by the contraction Nasakom, in which Sukarno returned to his 1920s attempts to work out a synthesis of nationalism (nasionalisme), religion (agama), and communism (komunisme). These ideas formed the basis of what was increasingly seen as a state ideology, printed up in fat, red-covered books to be used in obligatory indoctrination sessions for civil servants and students, and expressed in a rising rhetoric that excoriated the nation’s internal and external enemies. *

What was once Sukarno’s gift for effecting conciliation and workable synthesis now turned sour, and, even to many of its earlier supporters, the promise of Guided Democracy seemed empty. The economy worsened and fell into a spiral of uncontrolled inflation of more than 100 percent annually. The army, after 1962 part of a combined Armed Forces of the Republic of Indonesia (ABRI), and the PKI confronted each other increasingly aggressively for control of state and society. Sukarno, although casting himself as the great mediator and attempting to balance all ideological forces, appeared to grow more radically inclined, drawing closer to the PKI and its leader, D. N. Aidit (1923–65), and away from Nasution’s army. Widespread arrests of dissidents, censorship of media, and prohibition of “unhealthy” Western cultural influences (for example, dancing the Twist and listening to the Beatles) darkened Indonesia’s social and intellectual world. *

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025