JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF INDONESIA DURING WORLD WAR II

Japan invaded Indonesia in 1942. The occupation was to last for 42 months, from March 1942 until mid-August 1945, and this period properly belongs to Indonesia’s colonial era. Colonial rule by the Japanese in Indonesia in World War II was relatively mild. The Japanese occupation was more like another colonial period than a period of war. Many Indonesians at first welcomed them as Asian liberators who would end Dutch rule, but this optimism quickly evaporated. Japanese occupation proved far harsher than Dutch colonialism, and the years from 1942 to 1945 are widely remembered as a time of forced labor, hunger, and severe hardship. Much of the rice Indonesians were compelled to grow was shipped to Japan, leaving local communities near starvation. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

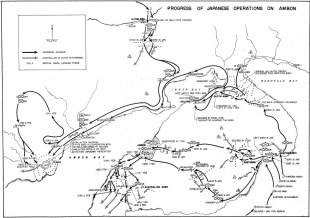

Indonesians who had cautiously welcomed the idea of a Japanese victory because it might advance a nationalist agenda were disappointed by Japan’s initial actions. The idea that the colony might form a national unit did not appeal to the new power, which divided the territory administratively between the Japanese Imperial Army and the Japanese Imperial Navy, with the Sixteenth Army in Java, the Twenty- fifth Army in Sumatra (but headquartered until 1943 in Singapore, afterwards in Bukittinggi, western Sumatra), and the navy in the eastern archipelago. [Source: Library of Congress *]

As late as May 1943, these areas were—unlike the Philippines and Burma—slated to remain permanent imperial possessions, colonial territories rather than autonomous states, within the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Some Japanese pan-Asianists and national idealists did have notions that Japan’s true duty was to bring independence to Indonesia, but they had little real influence on imperial policy. And less than two weeks after the Dutch surrender, the Japanese military government on Java not only banned all political organizations but prohibited the use of the red-and-white flag and the anthem “Indonesia Raya.” Similar restrictions were enforced even more stringently in the other administrative areas. *

Many Indonesians, at least initially, welcomed the Japanese as liberators of Dutch rule more open to the idea of Indonesian independence. As time wore on Indonesians became increasingly unhappy under Japanese rule. Some Indonesian women and a few Dutch women became sex slaves. But in some ways the bad things the Japanese did were the same or not much worse than what the Dutch did. So they would not be held in violation of the Geneva Convention Japanese demanded that Dutch sex slaves sign formal contacts. No such formalities were done with local Indonesian women.

The occupation was not gentle. Japanese troops often acted harshly against local populations. The Japanese military police were especially feared. Food and other vital necessities were confiscated by the occupiers, causing widespread misery and starvation by the end of the war. The worst abuse, however, was the forced mobilization of some 4 million — although some estimates are as high as 10 million — romusha (manual laborers), most of whom were put to work on economic development and defense construction projects in Java. About 270,000 romusha were sent to the Outer Islands and Japanese-held territories in Southeast Asia, where they joined other Asians in performing wartime construction projects. At the end of the war, only 52,000 were repatriated to Java. *

RELATED ARTICLES:

INDONESIA IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

WORLD WAR II CAMPAIGNS IN THE SOLOMON ISLANDS, NEW GUINEA AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

RISE OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA DECLARES INDEPENDENCE IN 1945 AT THE END OF WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA’S NATIONAL REVOLUTION: THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE 1945-1949 factsanddetails.com

INDONESIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE (1945-1949): POLICE ACTION, ATROCITIES, MASSACRES factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA OFFICIALLY ACHIEVES INDEPENDENCE factsanddetails.com

DIFFICULTY MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK IN INDONESIA IN THE 1950s factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

Japanese Administration of Indonesia in World War II

The Japanese divided the Indies into three jurisdictions: Java and Madura were placed under the control of the Sixteenth Army; Sumatra, for a time, joined with Malaya under the Twenty-fifth Army; and the eastern archipelago was placed under naval command. In Sumatra and the east, the overriding concern of the occupiers was maintenance of law and order and extraction of needed resources. Java's economic value with respect to the war effort lay in its huge labor force and relatively developed infrastructure. The Sixteenth Army was tolerant, within limits, of political activities carried out by nationalists and Muslims. This tolerance grew as the momentum of Japanese expansion was halted in mid-1942 and the Allies began counteroffensives. In the closing months of the war, Japanese commanders promoted the independence movement as a means of frustrating an Allied reoccupation. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Sukarno and Hatta agreed in 1942 to cooperate with the Japanese, as this seemed to be the best opportunity to secure independence. The occupiers were particularly impressed by Sukarno's mass following, and he became increasingly valuable to them as the need to mobilize the population for the war effort grew between 1943 and 1945. His reputation, however, was tarnished by his role in recruiting romusha. *

Japanese attempts to coopt Muslims met with limited success. Muslim leaders opposed the practice of bowing toward the emperor (a divine ruler in Japanese official mythology) in Tokyo as a form of idolatry and refused to declare Japan's war against the Allies a "holy war" because both sides were nonbelievers. In October 1943, however, the Japanese organized the Consultative Council of Indonesian Muslims (Masyumi), designed to create a united front of orthodox and modernist believers. Nahdatul Ulama was given a prominent role in Masyumi, as were a large number of kyai (religious leaders), whom the Dutch had largely ignored, who were brought to Jakarta for training and indoctrination. *

As the fortunes of war turned, the occupiers began organizing Indonesians into military and paramilitary units whose numbers were added by the Japanese to romusha statistics. These included the heiho (auxiliaries), paramilitary units recruited by the Japanese in mid-1943, and the Defenders of the Fatherland (Peta) in 1943. Peta was a military force designed to assist the Japanese forces by forestalling the initial Allied invasion. By the end of the war, it had 37,000 men in Java and 20,000 in Sumatra (where it was commonly known by the Japanese name Giyugun). In December 1944, a Muslim armed force, the Army of God, or Barisan Hizbullah, was attached to Masyumi. *

Indonesians During the Japanese Occupation

Generalizing about Indonesia during the 1942–45 occupation period is extraordinarily difficult, not only because of varying policies and conditions in the separate administrative divisions, but also because circumstances changed rapidly over time, particularly as the war turned against Japan, and because Indonesians’ experience varied widely according to, among other things, their social status and economic position. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The occupation is remembered as a harsh time. Japanese military rule was severe, and fear of arrest by the Kenpeitai (military police) and of the torture and execution of those who defied or were suspected of defying the Japanese was widespread. Particularly after mid-1943, economic conditions worsened markedly as a result of the wartime disruption of transportation and commerce, as well as misguided economic policies. Most urban populations were protected from extremes by government rationing of necessities, but severe food shortages and malnutrition developed in some areas, and cloth and clothing became so scarce by 1944 that villagers in some regions were reduced to wearing crude coverings made of old sacking or sheets of latex. *

The unrelenting mobilization of laborers—generally lumped under the infamous Japanese term “rōmusha “(literally, manual workers but in Indonesia always taken to mean forced labor)— came to represent in both official and public Indonesian memory the cruelty and repression of Japanese rule. Exact numbers are impossible to determine, but the Japanese drafted several million Javanese for varying lengths of time, mostly for local projects. As many as 300,000 may have been sent outside of Java, nearly half of them to Sumatra and others as far away as Thailand. It is not known how many actually returned at the end of the war, although about 70,000 are recorded as being repatriated from places other than Sumatra by Dutch services; nor is it clear how many “rōmusha “died, were injured, or fell ill. But the casualties were undoubtedly very high, for in most cases the conditions were extremely grim. *

The new “priyayi “and the urban middle classes, however, were often shielded from these extremes and often took a more equivocal attitude toward Japanese rule. They filled many of the positions left vacant by Dutch civil servants interned by the Japanese, and also vied for “pangreh praja “positions dominated by members of the traditional elite or those who had attended government schools. They also applauded the Japanese policies that ended dualism in education and the courts, and were receptive to Japanese pan-Asian East-versus-West sensibilities (“Asia for the Asians” as opposed to white supremacy, and “Asian values” as opposed to “Western materialism”). *

The “priyayi “and the middle classes also recognized the enormous advantages nationalist leaders had, however much the Japanese sought to control them, when they appeared before huge crowds and were featured in the newspapers or on the radio. Few expected much from the obviously propagandistic Japanese efforts to mobilize public support through a series of mass organizations, such as the Center of the People’s Power (Putera) and the Jawa Hōkōkai (Java Service Association), or from the “political participation” promised through advisory groups formed at several administrative levels, including the Chūō Sangi-In (Central Advisory Council) for Java. Observers began to notice, however, that Sukarno and Hatta, both of whom had been released from Dutch internment by the Japanese in 1942, managed to slip nationalist language into their speeches, and the formation of the volunteer army known as Defenders of the Fatherland (Peta) in late 1943 was seen as an enormous step in furthering nationalist goals, one that of course could never have taken place under the Dutch. *

Comfort Women During the Japanese Occupation of East Timor

Stephanie Coop wrote in the Japan Times, “Ines de Jesus was a young girl during World War II when she was forced to become a sex slave, or “comfort woman,” for Japanese troops in the then Portuguese colony of East Timor. By day, de Jesus carried out various kinds of menial labor, and each night was raped by between four to eight Japanese soldiers at a so-called comfort station in Oat village in the western province of Bobonaro. While horrific, de Jesus’ experience with sexual abuse under military occupation is by no means unusual among East Timorese women, as a special exhibition at the Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace in Tokyo’s Shinjuku Ward makes clear. [Source: Stephanie Coop, Japan Times, December 23, 2006 |::|]

Twenty-one comfort stations were identified by a team led by Kiyoko Furusawa, an associate professor of development and gender studies at Tokyo Woman’s Christian University. “Japanese landed in East Timor in February 1942 to oust a contingent of Australian troops that had entered the neutral territory the previous December, it ordered “liurai” (traditional kings) and village heads to supply women to serve the troops. Some of those who refused to comply were executed. “Women enslaved in comfort stations were forced to serve many soldiers every night, while others were treated as the personal property of particular officers,” she said. “Some women were specifically targeted for enslavement because their husbands were suspected of aiding the Australian troops. “As well as being physically and psychologically traumatized by the sexual abuse, the women were also made to work at tasks such as building roads, cutting wood, growing and preparing food, and doing laundry during the day, so they were constantly exhausted. They were also forced to dance and were taught Japanese songs to entertain soldiers,” Furusawa said. |::|

“Comfort women received no payment for their work and little or no food, she added. Family members either brought food to the comfort stations or the women were sent home to obtain it. There was little likelihood of women trying to escape at such times, she explained. “There were around 12,000 Japanese troops in a country with a population of only about 463,000, so the whole island was like an open prison. There was nowhere for the women to go, and at any rate, they were terrified about reprisals against their families if they did try to escape.” |::|

“Despite the gravity of the human-rights abuses documented in the exhibition, justice has yet to be achieved for the survivors. Japan’s system of sexual slavery was largely ignored in the war crimes trials conducted by the Allies after World War II, and a special court established by Indonesia to punish the atrocities committed by its troops and militias in 1999 failed to get a single rape indictment. |::|

“Citizen groups concerned about the lack of accountability for the wartime sex-slave atrocities convened a people’s tribunal in Tokyo in 2000 that found the late Emperor Hirohito and high-ranking Japanese military officers guilty of crimes against humanity. The verdict was later censored from an NHK documentary on the trial amid allegations by a major daily newspaper that two heavyweight Liberal Democratic Party politicians — Shoichi Nakagawa and Shinzo Abe — paid a less than comfortable visit to the public broadcaster before it was aired. Furusawa said that while the tribunal helped restore some dignity to victims by publicly acknowledging that the acts they were subjected to constituted violations of international law, only an official apology and compensation from the Japanese government will satisfy the survivors’ demands for justice.” |::|

Impact of Japanese Occupation on Indonesian Nationalism and Independence

The occupation of Indonesia by the Japanese gave the Indonesian nationalist movement a boost and help paved the way for the independence movement after the end of the war. Indonesians were given more control over their own affairs. A military mentality was developed there that endues to this day. Japanese-trained youth militias set up to defend the country gave rise to the pemuda (youth groups) of the independence movement, many of whom would later join the Republican army. [Source: Lonely Planet]

The Japanese occupation was a watershed in Indonesian history. It shattered the myth of Dutch superiority, as Batavia gave up its empire without a fight. There was little resistance as Japanese forces fanned out through the islands to occupy former centers of Dutch power. The relatively tolerant policies of the Sixteenth Army on Java also confirmed the island's leading role in Indonesian national life after 1945: Java was far more developed politically and militarily than the other islands. In addition, there were profound cultural implications from the Japanese invasion of Java. [Source: Library of Congress *]

In administration, business, and cultural life, the Dutch language was discarded in favor of Malay and Japanese. Committees were organized to standardize Bahasa Indonesia and make it a truly national language. Modern Indonesian literature, which got its start with language unification efforts in 1928 and underwent considerable development before the war, received further impetus under Japanese auspices. Revolutionary (or traditional) Indonesian themes were employed in drama, films, and art, and hated symbols of Dutch imperial control were swept away. For example, the Japanese allowed a huge rally in Batavia (renamed Jakarta) to celebrate by tearing down a statue of Jan Pieterszoon Coen, the seventeenthcentury governor general. Although the occupiers propagated the message of Japanese leadership of Asia, they did not attempt, as they did in their Korean colony, to coercively promote Japanese culture on a large scale. According to historian Anthony Reid, the occupiers believed that Indonesians, as fellow Asians, were essentially like themselves but had been corrupted by three centuries of Western colonialism. What was needed was a dose of Japanese-style seishin (spirit; semangat in Indonesian). Many members of the elite responded positively to an inculcation of samurai values. *

The most significant legacy of the occupation, however, was the opportunities it gave for Javanese and other Indonesians to participate in politics, administration, and the military. Soon after the Dutch surrender, European officials, businessmen, military personnel, and others, totaling around 170,000, were interned (the harsh conditions of their confinement caused a high death rate, at least in camps for male military prisoners, which embittered Dutch-Japanese relations even in the early 1990s). While Japanese military officers occupied the highest posts, the personnel vacuum on the lower levels was filled with Indonesians. Like the Dutch, however, the Japanese relied on local indigenous elites, such as the priyayi on Java and the Acehnese uleebalang, to administer the countryside. Because of the harshly exploitative Japanese policies in the closing years of the war, after the Japanese surrender collaborators in some areas were killed in a wave of local resentment. *

Sukarno and Other Political Leaders During the Japanese Occupation

Both Sukarno and Hatta agreed to cooperate with the Japanese in the belief that Tokyo was serious about leading Indonesia toward independence; they were, in any case, convinced that outright refusal was too dangerous. (Syahrir declined to play a public role.) Their cooperation was a dangerous game, which later earned both leaders criticism, especially from the Dutch and the Indonesian political left, for having been “collaborators.” Sukarno’s role in recruiting “rōmusha “became a particularly sore issue, although he later stubbornly defended his actions as necessary to the national struggle. Some Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama leaders followed Sukarno’s cooperative lead, seeing no reason why, if the Japanese were trying to use them to mobilize Muslim support, they should not use the Japanese to advance Muslims’ agenda. They saw some advantage in the formation of the Consultative Council of Indonesian Muslims (Masyumi), which brought modernist and traditionalist Muslim leaders together, and of its military wing, the Barisan Hisbullah (Army of God), intended as a kind of Muslim version of Peta. But on the whole, Muslim enthusiasm for cooperation with the Japanese did not match Sukarno’s. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Another group that was initially enthusiastic about the Japanese victory was made up of somewhat younger (mostly under 30), less established, but educated, urban, and mostly male, individuals. Many had been jailed or under surveillance in the late Dutch period for their political activism. They were courted by the Japanese and filled positions in news agencies, publishing, and the production of propaganda. Referred to loosely as “pemuda” (young men), they rapidly developed nationalist sentiments, eventually turning bitterly against Japanese tutelage and coming to play an important role in events after the occupation. *

Legacy of the Japanese Occupation on Indonesia

Donald Greenlees wrote in the New York Times, “Unlike in other countries in East Asia, Japan's occupation of Indonesia - which took place from 1942 to 1945 - elicits ambivalent responses from local people today. There is none of the bitter hostility that has erupted in China's or Korea's relations with Japan - perhaps because of the benefit of geographic distance. The Japanese conquest in 1942, which caused the Dutch to flee, undoubtedly hastened Indonesian independence. Later, Japanese development aid and investment was a major contributor to Indonesia's industrialization and remarkable economic growth. [Source: Donald Greenlees, New York Times, August 15, 2005 ]

“The legacy of Japanese wartime rule is still present in ways both great and small: Indonesia's 1945 Constitution was written by committees of nationalists brought together by the Japanese, and a nationwide system of neighborhood chiefs and committees was implemented during the Japanese occupation. Yet, Indonesia also suffered during the occupation, if not to the same degree as China or Korea. There is no accurate record of the number of women forced into sex slavery - to be so-called comfort women - but it is thought to be in the thousands. Historians estimate that there were at least 200,000 forced laborers, or Romusha, more than half of whom died. Periodic uprisings were brutally suppressed.

“Salim Said, a military analyst at the Center for National Strategic Studies in Jakarta, captures the current feeling of ambivalence when he describes the occupation as "a blessing in disguise." From the time of their arrival, the officers of the Japanese administration embarked on a program of social mobilization with the aim of garnering support for the war effort. They organized political advisory councils, self-defense militias, and religious, youth and women's groups. And they adopted the nationalist term for the Dutch East Indies - "Indonesia." "The Japanese could not use the machine that they created," Said said. "When we proclaimed our independence it was easy to get support from the mass of the public because they were already mobilized by Japan."

“But the Japanese occupation also influenced Indonesia in less fortunate ways. Some historians believe the authors of the 1945 Constitution were influenced by the Japanese political model when they created a powerful presidency and hence the opportunity for authoritarian rule. It was not until 2003 that the Constitution was significantly reformed. Among the young soldiers to be trained by the Japanese were many of Indonesia's future political and military leaders, including Suharto, the second president, who served for 32 years. The experience, according to Said, imbued authoritarian habits in them. "The memory, experience imprinted in their souls under the Japanese played an important role in the way they shaped society," he said. Suharto's first overseas visit as president was to Tokyo in 1968. But it was not a sentimental journey. He went in search of development aid and investment.

“Japan was to become Indonesia's most important benefactor. In recent years, Indonesia has often taken the largest slice of Japan's aid budget, and Tokyo's annual aid grants have topped $1 billion. About 1,000 Japanese companies are set up in the Jakarta area alone, according to the Jakarta Japan Club. The money has paid diplomatic dividends. Peter McCawley, the Tokyo-based dean of the Asian Development Bank Institute and an Indonesia specialist, remembers sitting next to Indonesia's senior economics minister, Wijoyo Nitisastro,at an international aid forum for which Japan played host Japan 10 years ago. McCawley recalled Wijojo leaning over to him and saying of the Japanese: "These people have given us a lot of support over the years. They have been very good to us."

Because of the aid and investment, the Indonesian government has been wary of getting mired in historical debates. The issue of official war reparations was settled under a 1958 treaty and has not been reopened despite later revelations about the existence of comfort women. Said, the military analyst, said that in the early 1970s the Japanese Embassy protested the imminent release of an Indonesian film called "Romusha," depicting the story of forced laborers. But there was a typically Indonesian solution. Said, then a film critic, said the embassy was allowed to buy the rights to the film. It was never publicly shown. Around that time the relationship between Jakarta and Tokyo was particularly sensitive. Indonesian students, angry over the direction of economic policy, were critical of the influence and pervasiveness of Japanese investment. During a visit to Jakarta by Prime Minister Kakuei Tanakain January 1974, there were student riots that aimed at Japanese businesses and cars.

“Today, concerns about the crimes of the occupation are dying with the victims. Ines Thioren Situmorang, a 28-year-old lawyer with the Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation, remembers that her elementary school textbooks taught that comfort women were simply prostitutes. "The current generation perceives comfort women as part of a system of voluntary prostitution. That is what our schools teach here," she said.”

Japanese Who Helped in Indonesian Struggle for Independence

Donald Greenlees wrote in the New York Times, “When the war ended, Hideo Fujiyama had to choose where his true loyalties lay. He decided not to return to Japan, but to stay in Indonesia, a country he barely knew. His decision to desert the Japanese Army was motivated by a mix of reasons, both practical and sentimental. He had been accidentally left behind when his unit shifted base. But he was also resentful at the way he had been treated in the wartime army, had an ill-defined sense that he could have a better life in the tropics and was inspired by Indonesia's burgeoning nationalist movement. Witnessing a stirring call for independence by Sukarno, the nationalist leader who later became Indonesia's first president, at a mass rally in Jakarta on Sept. 19, 1945, was a turning point. "He was so energetic and impressive," said Fujiyama, at the time a sergeant in an aircraft maintenance unit. "I was so moved by Sukarno's speech." [Source: Donald Greenlees, New York Times, August 15, 2005 ]

“Fujiyama joined the rapidly forming Indonesian nationalist military forces. He was one of about 1,000 Japanese troops in Indonesia to desert and stay behind to fight for the country's independence from the returning Dutch colonial power. The vital role of Japanese veterans in the postwar independence struggle is a largely overlooked chapter of Indonesia's recent history. The Japanese deserters provided tactical leadership, weapons and training to the ramshackle Indonesian forces. Although there was a modest contribution to the ultimate victory over the Dutch in 1949, it illustrated the varied and complex part played by Japan in Indonesia's attainment of independence and development as a nation.

Most of Japanese were on the islands of Sumatra, Java and Bali, after the Japanese surrendered to the Allies on Aug. 15, 1945. Based on interviews with a Japanese soldier in Indonesia, the Japanese writer Eichii Hayashi told Kyodo some Japanese soldiers stayed by choice, either because they already had local girlfriends or wives, or they just were looking to survive or had other reasons. Many also feared court-martial or being tried as a war criminal. According to Hayashi, among those fighting for Indonesia’s independence, only a few were really inspired by the country’s burgeoning nationalist movement. The Japanese soldiers are nowadays known in Japanese as “zanryu Nihon-hei” or Japanese soldiers who stayed behind. But at one time, they were also labeled “dasso Nihon-hei” or Japanese deserters. [Source: Christine T. Tjandraningsih, Kyodo, August 19, 2011 \~]

Hayashi told Kyodo, the contribution of the Japanese soldiers doesn’t appear in either Japanese or Indonesian history textbooks. At the Proclamation Museum in Central Jakarta, the historic site of the country’s declaration of independence, there is a permanent display detailing the role of the Japanese colonialists in the events leading up to Aug. 17, 1945, the date independence was declared and armed resistance officially began. Among the details is how Adm. Tadashi Maeda, chief of the Imperial Japanese Army’s liaison office in Indonesia, provided the late President Sukarno, late Vice President Mohammad Hatta and other key figures of the independence movement the use of his house to make their proclamation. The museum also covers the 1945-1950 guerilla war, but the display doesn’t mention the Japanese soldiers who provided them with arms, weapons training and military strategy. \~\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025