INDONESIA FORMALLY GRANTED INDEPENDENCE

On December 27 1949, shortly after hostilities with the Dutch ended, the Dutch formerly granted independence to Indonesia. The Indonesian flag, the Merah Putih, was raised over Jakarta’s Istana Merdeka (Freedom Palace). The Indonesians were the first Asian people to win independence by armed struggle, which ended with Indonesian independence and the Netherlands’ withdrawing all it forces from Indonesian and recognizing Indonesian sovereignty. In 1950, Indonesia adopted a unitary parliamentary system under a new constitution, with Sukarno as president and Hatta as prime minister, and joined the United Nations as its 60th member.

For a time Indonesia was called the United States of Indonesia. On August 17, 1950, the names was changed to the Republic of Indonesia. Indonesian independence brought about many name changes: Celebes became Sulawesi and it capital Makassare became Ujung Pandang (later it went back to Makassare) . The slogan “Unity in Diversity” was pushed on Indonesians. Indonesia adopted a democratic constitution in 1950 and elections were held n 1955. All ties with the Netherlands were ended in 1956.

In January 1949, the United Nations Security Council passed a resolution demanding the reinstatement of the republican government. The Dutch were also pressured to accept a full transfer of authority in the archipelago to Indonesians by July 1, 1950. The Round Table Conference was held in The Hague to determine the means by which the transfer could be accomplished. Parties to the negotiations were the republic, the Dutch, and the federal states that the Dutch had set up following their police actions. [Source: Library of Congress *]

After two efforts at cease-fires between May and August 1949, the Round Table Conference met in The Hague from August 23 to November 2 to reach the final terms of a settlement. The result of the conference was an agreement that the Netherlands would recognize the RUSI (Republic of the United States of Indonesia; Indonesian: Republik Indonesia Serikat, RIS) as an independent state, that all Dutch military forces would be withdrawn, and that elections would be held for a Constituent Assembly. Two particularly difficult questions slowed down the negotiations: the status of West New Guinea, which remained under Dutch control, and the size of debts owed by Indonesia to the Netherlands, an amount of 4.3 billion guilders being agreed upon. *

The Round Table Agreement provided that the Republic and 15 federated territories established by the Dutch would be merged into a Federal Republic of Indonesia (RIS). The Dutch recognized the sovereignty of Indonesia on December 27, 1949. In December 1955, after Indonesia’s first election, the long-awaited Constituent Assembly was elected to draft a constitution to replace the provisional constitution of 1950. The membership was largely the same as the DPR. The assembly convened in November 1956 but became deadlocked over issues such as the Pancasila as the state ideology and was dissolved in 1959.

Originally the Dutch did not want Indonesia to take control of West Papua (the western half of New Guinea, Irian Jaya), but in 1963, the U.N. officially turned over the territory to Indonesia. Since Indonesia established independence, there have been several revolts to secure independence or autonomy for a particular region but none of them were successful until East Timor, won its independence in 1999. See East Timor.

RELATED ARTICLES:

INDONESIA DECLARES INDEPENDENCE IN 1945 AT THE END OF WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA’S NATIONAL REVOLUTION: THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE 1945-1949 factsanddetails.com

INDONESIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE (1945-1949): POLICE ACTION, ATROCITIES, MASSACRES factsanddetails.com

RISE OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF THE DUTCH EAST INDIES (1942-1945) factsanddetails.com

DIFFICULTY MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK IN INDONESIA IN THE 1950s factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO AS PRESIDENT: CHALLENGES, AUTHORITARIANISM, GUIDED DEMOCRACY factsanddetails.com

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNDER SUKARNO: NON-ALIGNMENT, ISOLATION, WAR WITH MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

Deal for Indonesian Independence Hammer Out

In January 1949, the United Nations Security Council passed a resolution demanding the reinstatement of the republican government. The Dutch were also pressured to accept a full transfer of authority in the archipelago to Indonesians by July 1, 1950. The Round Table Conference was held in The Hague to determine the means by which the transfer could be accomplished. Parties to the negotiations were the republic, the Dutch, and the federal states that the Dutch had set up following their police actions. [Source: Library of Congress *]

After two efforts at cease-fires between May and August 1949, the Round Table Conference met in The Hague from August 23 to November 2 to reach the final terms of a settlement. The result of the conference was an agreement that the Netherlands would recognize the RUSI (Republic of the United States of Indonesia; Indonesian: Republik Indonesia Serikat, RIS), as an independent state, that all Dutch military forces would be withdrawn, and that elections would be held for a Constituent Assembly. Two particularly difficult questions slowed down the negotiations: the status of West New Guinea, which remained under Dutch control, and the size of debts owed by Indonesia to the Netherlands, an amount of 4.3 billion guilders being agreed upon. *

The Round Table Agreement provided that the Republic and 15 federated territories established by the Dutch would be merged into a Federal Republic of Indonesia (RIS). The Dutch recognized the sovereignty of Indonesia on December 27, 1949. *

Post-Independence Indonesia

Developments during the first 15 years of Indonesia’s independent history have been comparatively little studied in recent years and tend to be explained in rather simple, dichotomous terms of, for example, a struggle between “liberal democracy” and “primordial authoritarianism,” between pragmatic “problem solvers” and idealistic “solidarity builders,” or between political left and right. These analyses are not entirely wrong, for Indonesia was indeed polarized during these years, but they tend to oversimplify the poles, and to ignore other parts of the story, such as the remarkable flourishing of literature and painting that drew on the sense of personal and cultural liberation produced by the National Revolution. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The new government also had extraordinary success, despite a lack of funds and expertise, in the field of education: in 1930 adult literacy stood at less than 7.5 percent, whereas in 1961 about 47 percent of those over the age of 10 were literate. It was a considerable achievement, too, that Indonesia in 1955 held honest, well-organized, and largely peaceful elections for an eligible voting public of nearly 38 million people scattered throughout the archipelago, more than 91 percent of whom cast a ballot. Still, it is fair to characterize the period as one of heavy disillusion as well, in which the enormously high expectations that leaders and the public had for independence could not be met, and in which the search for solutions was both intense and fragmented. While it may be true, as historian Anthony Reid has suggested, that the Revolution succeeded in “the creation of a united nation,” in 1950 that nation was still no more than a vision, and it remained to be seen whether the same ideas that had brought it to life could also be used to give it substance. *

Perhaps the greatest expectation of independence, shared by middle and lower classes, rural as well as urban dwellers, was that it would bring dramatic economic improvement. This hope had been embedded in the nationalist message since at least the 1920s, which had played heavily on the exploitative nature of the colonial economy and implied that removal of colonial rule would also remove obstacles to economic improvement and modernization. But the conditions Indonesia inherited from the eras of occupation and Revolution were grim, far grimmer than those of neighboring Burma or the Philippines, for example, despite the fact that unlike them it had not been a wartime battlefield. The Japanese had left the economy weak and in disarray, but the Revolution had laid waste, through fighting and scorched-earth tactics, much of what remained. In 1950 both gross domestic product and rice production were well below 1939 levels, and estimated foreign reserves were equivalent to about one month’s imports (and only about three times what they had been in 1945). In addition, provisions in the Round Table Agreement had burdened Indonesia with a debt to the Netherlands of US$1.125 billion dollars and saddled it with the costs of integrating thousands of colonial administrative and military personnel. (No other ex-colony in the postwar era was faced with such a debt, 80 percent of which Indonesia had paid when it abrogated the agreement in 1956.)

Indonesia’s First Election in 1955

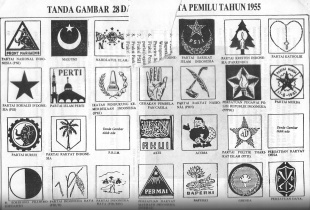

Indonesia’s first elections were held n 1955, six years after independence was official achieved. Sukarno’s party, PNI, won the most votes but did not win a majority. The Communists (the PKI) also did well. Sukarno was unable to form a government and unstable coalitions continued. In 1956, Sukarno criticized parliamentary democracy, saying it was based on “inherent confect.” His attempt to create a unifying government based on nationalism religion and communism—chosen in part because they represented the three main political factions, the military, Islamic parties and the communists—was largely a failure.

It was a considerable achievement, that Indonesia in 1955 held honest, well-organized, and largely peaceful elections for an eligible voting public of nearly 38 million people scattered throughout the archipelago, more than 91 percent of whom cast a ballot. [Source: Library of Congress]

Indonesia’s unitary political system, as defined by a provisional constitution adopted by the legislature on August 14, 1950, was a parliamentary democracy: governments were responsible to a unicameral House of Representatives elected directly by the people. Sukarno became president under the new system. His powers, however, were drastically reduced compared with those prescribed in the 1945 constitution. Elections were postponed for five years. They were postponed primarily because a substantial number of Dutch-appointed legislators from the RUSI system remained in the House of Representatives, a compromise made with the Dutch-created federal states to induce them to join a unitary political system. The legislators knew a general election would most likely turn them out of office and tried to postpone one for as long as possible.

Troubles for the New Indonesian Government

Because of widespread fear by nationalists in the Republic and in some of the federated territories that the structural arrangements of the RIS would favor pro-Dutch control, and because the TNI also found it unthinkable that they should be required to merge with the very army and police forces they had been fighting against, there was considerable sentiment in favor of scrapping the federal arrangement. This, and often heavy-handed pressure from within the Republican civilian bureaucracy and army, produced within five months a dissolution of the RIS into a new, unitary Republic of Indonesia, which was officially declared on the symbolic date of August 17, 1950. Only the breakaway Republic of South Maluku (RMS) resisted this incorporation. TNI forces opposed and largely defeated the RMS in the second half of 1950, but about 12,000 of its supporters were relocated to the Netherlands, and there and in Maluku itself separatist voices were heard for the next half- century.

The RUSI, an unwieldy federal creation, was made up of sixteen entities: the Republic of Indonesia, consisting of territories in Java and Sumatra with a total population of 31 million, and the fifteen states established by the Dutch, one of which, Riau, had a population of only 100,000. The RUSI constitution gave these territories outside the republic representation in the RUSI legislature that was far in excess of their populations. In this manner, the Dutch hoped to curb the influence of the densely populated republican territories and maintain a postindependence relationship that would be amenable to Dutch interests. But a constitutional provision giving the cabinet the power to enact emergency laws with the approval of the lower house of the legislature opened the way to the dissolution of the federal structure. By May 1950, all the federal states had been absorbed into a unitary Republic of Indonesia, and Jakarta was designated the capital. *

The consolidation process had been accelerated in January 1950 by an abortive coup d'état in West Java led by Raymond Paul Pierre "The Turk" Westerling, a Dutch commando and counterinsurgency expert who, as a commander in the Royal Netherlands Indies Army (KNIL), had used terroristic, guerrilla-style pacification methods against local populations during the National Revolution. Jakarta extended its control over the West Java state of Pasundan in February. Other states, under strong pressure from Jakarta, relinquished their federal status during the following months. But in April 1950, the Republic of South Maluku (RMS) was proclaimed at Ambon. With its large Christian population and long history of collaboration with Dutch rule (Ambonese soldiers had formed an indispensable part of the colonial military), the region was one of the few with substantial pro-Dutch sentiment. The Republic of South Maluku was suppressed by November 1950, and the following year some 12,000 Ambonese soldiers accompanied by their families went to the Netherlands, where they established a Republic of South Maluku government-in-exile. *

Independent But Divided Indonesia

Although Indonesia was finally independent and (with the exceptions of Dutch-ruled West New Guinea and Portuguese-ruled East Timor) formally unified, the society remained deeply divided by ethnic, regional, class, and religious differences. The Dutch had wanted to set up a federal system, in which the different islands were largely sovereign but Sukarno and others were against the idea because it reminded them of the Dutch divide and rule governing style. They discredited this idea in favor of national unity.

The Republic movement was deeply divided, with Sukarno supporters, Communists and Islamists making up the major groups in a addition to regional and ethnic groups. The army had emerged as a powerful force but it too was sharply divided and on top of that it was feared and distrusted by some. Even before independence communists were brutally massacred by army force. A desire to throw the Dutch out was in many ways the only thing that unified the diverse groups. With the Dutch gone the Republican government started to unravel despite Sukarno’s best efforts to prevent that from happening.

New Military-Tinged Indonesian Government

The Japanese-trained military emerged as potential political force after the struggle for independence with the Dutch was over. Given its central role in the National Revolution, the military became deeply involved in politics. This emphasis was, after all, in line with what was later enunciated as its dwifungsi, or dual function, role of national defense and national development. The military was not, however, a unified force, reflecting instead the fractures of the society as a whole and its own historical experiences. In the early 1950s, the highest-ranking military officers, the so-called "technocratic" faction, planned to demobilize many of the military's 200,000 men in order to promote better discipline and modernization. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Most affected were less-educated veteran officers of Peta and other military units organized during the Japanese and revolutionary periods. The veterans sought, and gained, the support of parliamentary politicians. This support prompted senior military officers to organize demonstrations in Jakarta and to pressure Sukarno to dissolve parliament on October 17, 1952. Sukarno refused. Instead, he began encouraging war veterans to oppose their military superiors; and the army chief of staff, Sumatran Colonel Abdul Haris Nasution (born 1918), was obliged to resign in a Sukarno-induced shake-up of military commands. *

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025