JAPANESE INVASION OF INDONESIA IN WORLD WAR II

Allied Carrier strike on Surabaya in May 1944 near the end of the war

Following the fall of Singapore in February 1942, many Europeans fled to Australia, and the Dutch colonial government abandoned their colony. The Japanese Imperial Army marched into Batavia (Jakarta) on 5 March 1942, carrying the red and white Indonesian flag alongside that of the Japanese rising sun. Europeans were arrested and all signs of the former Dutch colonial government eliminated. Though the Japanese were greeted as liberators, public opinion turned against them as the war wore on and Indonesians were expected to endure more hardships for the war effort. [Source: Lonely Planet]

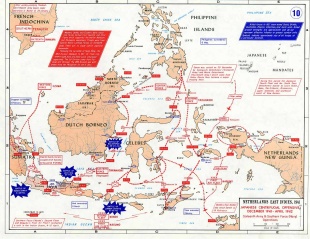

Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces moved into Southeast Asia. The occupation of the archipelago took place in stages, beginning in the east with landings in Tarakan, northeastern Kalimantan, and Kendari, southeastern Sulawesi, in early January 1942, and Ambon, Maluku, at the end of that month. At the beginning of February, Japanese forces invaded Sumatra from the north, and at the end of the month, the Battle of the Java Sea cleared the way for landings near Bantam, Cirebon, and Tuban, on Java, on March 1; Japanese forces met with little resistance, and the KNIL announced its surrender on March 8, 1942. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The Dutch East Indies were a valuable prize for the Japanese because the archipelago was rich in resources useful in warfare such as oil, rubber and tin. Japan’s decision to occupy the Netherlands East Indies was based primarily on the need for raw materials, especially oil from Sumatra and Kalimantan. The Japanese also used thousands of Indonesians as menial laborers to build roads and railways in Southeast Asia. They participated in the building of the bridge over the River Kwai. By some estimates more 10 million Indonesians were forced to work in forced labor projects, with 1 million dying in the process.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF THE DUTCH EAST INDIES (1942-1945) factsanddetails.com

WORLD WAR II CAMPAIGNS IN THE SOLOMON ISLANDS, NEW GUINEA AND INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

RISE OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA DECLARES INDEPENDENCE IN 1945 AT THE END OF WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA’S NATIONAL REVOLUTION: THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE 1945-1949 factsanddetails.com

INDONESIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE (1945-1949): POLICE ACTION, ATROCITIES, MASSACRES factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA OFFICIALLY ACHIEVES INDEPENDENCE factsanddetails.com

DIFFICULTY MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK IN INDONESIA IN THE 1950s factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

Background of the Japanese Invasion of Indonesia in World War II

The Japanese occupied the archipelago in order, like their Portuguese and Dutch predecessors, to secure its rich natural resources. Japan's invasion of North China, which had begun in July 1937, by the end of the decade had become bogged down in the face of stubborn Chinese resistance. To feed Japan's war machine, large amounts of petroleum, scrap iron, and other raw materials had to be imported from foreign sources. Most oil — about 55 percent — came from the United States, but Indonesia supplied a critical 25 percent. [Source: Library of Congress *]

From Tokyo's perspective, the increasingly critical attitude of the "ABCD powers" (America, Britain, China, and the Dutch) toward Japan's invasion of China reflected their desire to throttle its legitimate aspirations in Asia. German occupation of the Netherlands in May 1940 led to Japan's demand that the Netherlands Indies government supply it with fixed quantities of vital natural resources, especially oil. Further demands were made for some form of economic and financial integration of the Indies with Japan. Negotiations continued through mid-1941. The Indies government, realizing its extremely weak position, played for time. But in summer 1941, it followed the United States in freezing Japanese assets and imposing an embargo on oil and other exports. Because Japan could not continue its China war without these resources, the military-dominated government in Tokyo gave assent to an "advance south" policy. French Indochina was already effectively under Japanese control. A nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union in April 1941 freed Japan to wage war against the United States and the European colonial powers. *

The Japanese experienced spectacular early victories in the Southeast Asian war. Singapore, Britain's fortress in the east, fell on February 15, 1941, despite British numerical superiority and the strength of its seaward defenses. The Battle of the Java Sea resulted in the Japanese defeat of a combined British, Dutch, Australian, and United States fleet. On March 9, 1942, the Netherlands Indies government surrendered without offering resistance on land. *

Although their motives were largely acquisitive, the Japanese justified their occupation in terms of Japan's role as, in the words of a 1942 slogan, "The leader of Asia, the protector of Asia, the light of Asia." Tokyo's Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, encompassing both Northeast and Southeast Asia, with Japan as the focal point, was to be a nonexploitative economic and cultural community of Asians. Given Indonesian resentment of Dutch rule, this approach was appealing and harmonized remarkably well with local legends that a two-century-long non-Javanese rule would be followed by era of peace and prosperity. *

Japanese Capture of Indonesia

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Dutch declared war on Japan. The Japanese Imperial Army invaded the Dutch East Indies on January 1, 1942 under the pretext of creating the Greater East Asia Coprosperity Sphere. During the last week of February 1942, the Japanese defeated American, British and Dutch forces in the Battle of the Java Sea. The victory allowed Japan to break the Allied defensive perimeter (the Malay Barrier) and drive the Allied naval forces out of Southeast Asia, extending Japanese control to what is now Indonesia.

The Japanese took Indonesia from the Dutch colonialists for the most part without a fight. The Dutch didn't have a large military force in the Dutch East Indies (the Netherlands was occupied by the Germans by that time). The Dutch navy in Indonesia was virtually destroyed. The Dutch colonial government abandoned Batavia (Jakarta) and surrendered it to Japanese forces in March 1942. Japanese soldiers marched into Batavia carrying the Indonesian “Red and White” flag along with the Japanese flag. Members of the Royal Dutch Indian Army that remained were taken prisoner and transported to Singapore .

Indonesia was not a major military theater in World War II. No major battles were fought. After two months of heavy fighting the Dutch colonial army surrendered, the Dutch navy was virtually destroyed, and about 65,000 Dutch and Indonesian soldiers were sent to labor camps. Some ended up working in the Burma Railroad in Thailand. Others worked in mines in Japan. Some scholars have suggested that even before Pearl Harbor, the U.S. was determined to go to battle with Japan because the American government feared that the Japanese would restrict their access to the vast resources found in the Dutch East Indies.

Battles During the Japanese Invasion of Indonesia

World War II battles involving Indonesia primarily involved the swift Japanese conquest of the Dutch East Indies in early 1942, focusing on oil-rich areas like Sumatra (Palembang) and Borneo (Tarakan), culminating in the decisive Battle of the Java Sea that crushed Allied naval power.

Key engagements included the Battle of Ambon, the Battle of Badung Strait, and the fall of major cities, leading to Japanese occupation until 1945. During the engagement in Tarakan (Borneo), the Japanese rapidly took over this oil hub. Palembang (Sumatra), the home of critical oil refineries, was captured in February 1942. The Japanese victory at Ambon was followed by massacres of prisoners of war. A naval battle showcasing Japanese night-fighting superiority took place at .Badung Strait.

The Battle of the Java Sea on February 27, 1942, was a decisive naval battle of the Pacific campaign of World War II, with Allied navies suffering a decisive defeat at the hands of the Imperial Japanese Navy. This defeat occurred during a series of actions over successive days. It began when the main Combined Striking Force (CSF), consisting of two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and nine destroyers, led by Striking Force Commander Rear Admiral Karel Doorman of the Royal Netherlands Navy, attempted to intercept a Japanese troop convoy in the Java Sea. However, the CSF was intercepted by the convoy's larger escort forces. [Source: Wikipedia]

The battle began as a stalemate, but the Haguro, a Japanese heavy cruiser, altered its trajectory when she crippled the British heavy cruiser HMS Exeter with gunfire. Then, she torpedoed and sank the Dutch destroyer Kortenaer, causing temporary disorder in Doorman's fleet as the damaged Exeter withdrew. A subsequent gunfight between Allied and Japanese destroyers resulted in the sinking of the HMS Electra and shell damage to the Asagumo. Then, Doorman's force turned away, ending the daylight engagement as dusk fell.

However, under the cover of night, Doorman's ships attempted another attack. During this attack, the destroyer HMS Jupiter hit a Dutch mine and sank. The Japanese quickly discovered their plan and ambushed the Allied fleet with a stealthy, long-range torpedo attack from the Haguro and Nachi. One of Nachi's torpedoes hit the Dutch light cruiser Java, instantly blowing her apart and causing her to sink with almost all hands. The Dutch colonial government surrendered in March 1942.

Japanese Attacks on Australia

Gen. Douglas MacArthur set up his headquarters in Australia after he left the Philippines. On February 19, 1942, Japanese began its attack of Australia, with Japanese carrier-based aircraft raiding Darwin. Japanese planes bombed Northern Queensland several times in 1942. Darwin was bombed 64 times and nearly destroyed. "I remember the scare," the journalist Russ Terrill wrote: "My parents spoke darkly of Oriental barbarism, and excitement rose in our town when fishermen sighted a Japanese dingy off the coast."

Darwin, Broome and the New Guinean town of Port Moresby were bombed by the Japanese. Australian Diggers and Rats of Tobruk soldiers fought Japanese advancing across New Guinea on the Kokoda Trail towards Port Moresby and endured horrible conditions before finally defeating the Japanese at Milne Bay.

Australian troops played a large role in the defeat of Japanese troops in the Pacific in World War II. Some 560,000 Australians severed abroad during World War II and participated in campaigns in North Africa, New Guinea, Borneo, Germany, Japan and the Mediterranean. Worried about a Japanese invasion, American and Australian engineers and soldiers built the 1,000-mile road between Mount Isa and Darwin, linking north and south Australia, in 100 days. The Americans ended by the Japanese threat by defeating the Japanese in the Battle of the Coral Sea.

Japanese Occupation of Indonesia in World War II

Colonial rule by the Japanese in Indonesia in World War II was relatively mild. The Japanese occupation was more like another colonial period than a period of war. Many Indonesians, at least initially, welcomed the Japanese as liberators of Dutch rule more open to the idea of Indonesian independence. As time wore on Indonesians became increasingly unhappy under Japanese rule. Some Indonesian women and a few Dutch women became sex slaves. But in some ways the bad things the Japanese did were the same or not much worse than what the Dutch did. So they would not be held in violation of the Geneva Convention Japanese demanded that Dutch sex slaves sign formal contacts. No such formalities were done with local Indonesian women.

The occupation was to last for 42 months, from March 1942 until mid-August 1945, and this period properly belongs to Indonesia’s colonial era. Indonesians who had cautiously welcomed the idea of a Japanese victory because it might advance a nationalist agenda were disappointed by Japan’s initial actions. The idea that the colony might form a national unit did not appeal to the new power, which divided the territory administratively between the Japanese Imperial Army and the Japanese Imperial Navy, with the Sixteenth Army in Java, the Twenty- fifth Army in Sumatra (but headquartered until 1943 in Singapore, afterwards in Bukittinggi, western Sumatra), and the navy in the eastern archipelago. [Source: Library of Congress *]

As late as May 1943, these areas were—unlike the Philippines and Burma—slated to remain permanent imperial possessions, colonial territories rather than autonomous states, within the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Some Japanese pan-Asianists and national idealists did have notions that Japan’s true duty was to bring independence to Indonesia, but they had little real influence on imperial policy. And less than two weeks after the Dutch surrender, the Japanese military government on Java not only banned all political organizations but prohibited the use of the red-and-white flag and the anthem “Indonesia Raya.” Similar restrictions were enforced even more stringently in the other administrative areas. *

The occupation was not gentle. Japanese troops often acted harshly against local populations. The Japanese military police were especially feared. Food and other vital necessities were confiscated by the occupiers, causing widespread misery and starvation by the end of the war. The worst abuse, however, was the forced mobilization of some 4 million — although some estimates are as high as 10 million — romusha (manual laborers), most of whom were put to work on economic development and defense construction projects in Java. About 270,000 romusha were sent to the Outer Islands and Japanese-held territories in Southeast Asia, where they joined other Asians in performing wartime construction projects. At the end of the war, only 52,000 were repatriated to Java. *

See Separate Article: JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF THE DUTCH EAST INDIES (1942-1945) factsanddetails.com

Allied Offensive to Retake Indonesia

In early 1944, the Allied forces under General MacArthur, launched an operation from what is now Papua New Guinea to liberate the Dutch East Indies from Japanese occupation. Much of the fighting took place in and along the north coast of what is now West Papua (Irian Jaya) and in caves on the nearby island of Biak. People knew little about this part of the world until then.

The first objective of the operation was to capture Hollandia (Jayapura) which was achieved with the help of more than 80,000 Allied troops in what was the largest amphibious operation of the war in the southwestern Pacific. The second objective, the capture of Sarmi, was achieved despite heavy Japanese resistance. The third and primary object was the capture of Biak to gain access to its airfields. Allied intelligence underestimated the Japanese presence in the area and a series of bloody battles was the result. Fighting also took place along the souther coast of Irian Jaya. The Allies captured Merauke, which they thought the Japanese might use to launch an attack on Australia.

In April 1944, U.S. forces occupied the town of Hollandia (now called Jayapura) in Papua, and in mid-September Australian troops landed on Morotai, Halmahera (Maluku); toward the end of the month, Allied planes bombed Jakarta (as Batavia had been renamed) for the first time.

The move into Indonesia’s islands was part of the island hopping operation to free the Philippines. After Biak was captured the airfields and bases were used to capture islands between New Guinea and the Philippines. The Americans captured the Japanese air bases on Morotai, an island near Halmahera, in the northern Moluccas and used that airfield to bomb Manila. A Japanese soldier hide out on Morotai island until 1973 not realizing the war was over.

Key Events When the Allies Retook Indonesia at the Emd of World War II

During the Borneo Campaign (Operation Oboe), Australian troops landed to capture airfields at

Tarakan on May 1945, beginning the campaign. In July 1945 a major amphibious assault by Australian forces took place at Balikpapan to secure vital oilfields, overcoming Japanese resistance. Other operations focused on liberating the rest of Borneo, especially North Borneo, with significant Australian involvement.

There was some fighting even after Japan surrendered. Allied efforts to retake Indonesia after Japan's 1945 surrender focused less on large-scale invasions within the main islands like Java and Sumatra, and more on securing Borneo and surrounding areas but the real fight for control erupted after Japan's surrender, with Indonesian Republicans battling Dutch forces trying to re-establish colonial rule, notably in the bloody Battle of Surabaya (Oct-Nov 1945) and other clashes during the Indonesian National Revolution.

Japan remained in control of Indonesia temporarily after their surrender. An Allied Task Force arrives in late 1945. British and Commonwealth forces (under MacArthur's overall command) were tasked with disarming Japanese troops, but this coincided with the Indonesian declaration, leading to clashes with Indonesian nationalists.

Japanese Freedom Fighter in Post-World War II Indonesia

Christine T. Tjandraningsih of Kyodo wrote: “The Japanese book “Zanryu Nihon-hei no Shinjitsu” (“The True Story of a Japanese Soldier Who Stayed Behind”), written by Eiichi Hayashi and published in 2007, tells the true story of Sakari Ono, who fought alongside Indonesian independence troops against the Dutch colonial forces. Ono, whose Indonesian name is Rahmat, was one of an estimated 1,000 Japanese soldiers who deserted and stayed behind in Indonesia. [Source: Christine T. Tjandraningsih, Kyodo, August 19, 2011 \~]

“Born Sept. 26, 1918, in Hokkaido, Ono, who lost his left arm in the war, was in his early 20s when he was sent to Indonesia in the Imperial Japanese Army. During his assignment, he interacted with Indonesian soldiers. From them, he heard many stories of how badly Japanese soldiers had treated local people and how they felt that Japan might break its promise of granting independence to Indonesia. That became a turning point in his life, motivating him to join the rapidly forming Indonesian nationalist military forces. \~\

“Ono joined the Special Guerrilla Forces, led by another former Japanese soldier, Tatsuo “Abdul Rachman” Ichiki, fighting for Indonesian independence in East Java’s South Semeru Province. They also provided tactical leadership, weapons and training to the ramshackle Indonesian forces. In 1958, Ono was awarded the Bintang Veteran (Veteran Medal) by Sukarno and the Bintang Gerilya (Guerrilla Medal), which accords him a plot at Kalibata Heroes’ Cemetery in Jakarta. Since 1982, the Indonesian government has also extended an invitation to the former Japanese soldiers to attend the commemoration of Independence Day at the State Palace, showing how their contributions and sacrifices have come to be more widely recognized. \~\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025