INDONESIA’S ITS INDEPENDENCE ON AUGUST 17, 1945

Almost immediately after the Japanese surrendered, on August 17, 1945, Sukarno and Mohammed Hatta declared Indonesia's independence from Sukarno’s home in Jakarta. They had effectively been forced to make the declaration after being kidnapped by military youth groups. A new constitution was made the same year. The move was made with the tacit approval of the Japanese—who remained in Indonesia until a formal surrender to the British—before the Dutch had returned. It would be another four years, marked by sporadic fighting, before that declaration was realized.

When Japan surrendered in 1945, nationalist leaders Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta declared the independence of the Republic of Indonesia. Ironically, the political ideas that helped galvanize the nationalist movement—freedom, democracy, progress, and education—were learned in part through Dutch schools established under the early twentieth-century “ethical policy.” During the war, the Japanese had elevated Sukarno and Hatta into leadership roles and overseen the drafting of a constitution, inadvertently strengthening the nationalist cause. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

The Dutch refused to accept the proclamation and tried to reassert control over Indonesia. British troops entered Java in October 1945 to accept the surrender of the Japanese. The Dutch returned gradually. They tried to reassert control over Indonesia with the help of the British, who controlled Malaysia and much of Borneo.

The struggle that followed the proclamation of independence on August 17, 1945, and lasted until the Dutch recognition of Indonesian sovereignty on December 27, 1949, is generally referred to as Indonesia’s National Revolution. It remains the modern nation’s central event, and its world significance, although often underappreciated, is real. The National Revolution was the first and most immediately effective of the violent postwar struggles with European colonial powers, bringing political independence and, under the circumstances, a remarkable degree of unity to a diverse and far-flung nation of then 70 million people and geographically the most fragmented of the former colonies in Asia and Africa. [Source: Library of Congress *]

RELATED ARTICLES:

RISE OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF THE DUTCH EAST INDIES (1942-1945) factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA’S NATIONAL REVOLUTION: THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE 1945-1949 factsanddetails.com

INDONESIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE (1945-1949): POLICE ACTION, ATROCITIES, MASSACRES factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA OFFICIALLY ACHIEVES INDEPENDENCE factsanddetails.com

DIFFICULTY MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK IN INDONESIA IN THE 1950s factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO AS PRESIDENT: CHALLENGES, AUTHORITARIANISM, GUIDED DEMOCRACY factsanddetails.com

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNDER SUKARNO: NON-ALIGNMENT, ISOLATION, WAR WITH MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

Indonesia’s Proclamation of Independence

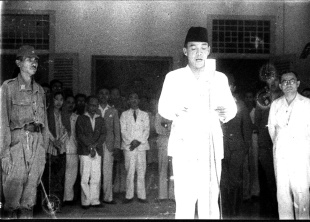

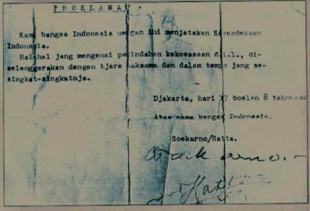

At exactly 10:00 am on Friday, August 17, 1945, at Jalan Pegangsaan Timur 56 in Jakarta, Indonesia’s political leaders, Sukarno and Hatta, proclaimed the Independence of the nation and people of Indonesia, with the statement: “PROKLAMASI : Kami, bangsa Indonesia, dengan ini menjatakan kemerdekaan Indonesia. Hal-hal jang mengenai pemindahan kekoeasaan,dll. diselenggarakan dengan tjara saksama dan dalam tempoh jang sesingkat-singkatnja. Djakarta, 17-8-'05. Wakil-wakil Bangsa Indonesia. (signed) Soekarno-Hatta”

“PROCLAMATION : We the People of Indonesia hereby declare the Independence of Indonesia. Matters which concern the transfer of power and other things will be executed by careful means and in the shortest possible time. Djakarta, 17 August 1945. In the Name of the People of Indonesia: signed Soekarno - Hatta.”

According to Indonesian accounts of the event: Thus spoke the sonorous and charismatic voice of Sukarno, which was followed by the historic first time hoisting of the Red and White Flag of this young Republic, for which so many people would later give up their lives.

This clarion call for independence was surreptitiously broadcast through radio to all corners of the archipelago, and the people across the islands responded with joy and determination to liberate their homeland, - then called the Netherlands East Indies, - from heinous colonialism, if need be through blood, sweat and tears.

Indonesia’s Proclamation for Independence came only two days after Japan surrendered to the Allied Forces under leadership of General MacArthur of the United States in Asia and the Pacific, marking the end of World War II. Japanese authorities, who then ruled the archipelago, had at first promised Indonesia’s political leaders: Sukarno and Hatta, that Japan would support the liberation of Indonesia. However, after their unconditional surrender, Japan had to retract this promise and keep the de facto position at prior to Japan’s occupation of the territory.

Soon Allied Forces under the Dutch descended on Indonesia to reclaim their territory, only to find strong armed resistance everywhere from the indigenous people who had been fired up by the Proclamation of Independence. And so, unlike British colonies, who were granted independence, Indonesia and the Indonesian people had to fight hard with many deaths for her Independence.

Only after long and hard battles and hundreds of thousands volunteer youg men and women killed in what is known as the Indonesian National Revolution, did the Netherlands Government finally concede to recognize the existence of the Republic of Indonesia in 1949, but not without proviso, involving a number of islands, notably in the eastern part of Indonesia.

Nonetheless, young Indonesia was adamant to reclaim the entire territory once colonized by the Dutch in the Netherlands East Indies — from Sabang on the island of Sumatra in the west to the town of Merauke on the island of Papua in the utmost eastern corner — to be the undivided territory of the new Republic of Indonesia. It was only in 1963 that the Netherlands finally relented to recognize the Independence of the entire Indonesian archipelago as we know today.

Indonesia after World War II

Unlike Burma and the Philippines, Indonesia was not granted formal independence by the Japanese in 1943. No Indonesian representative was sent to the Greater East Asia Conference in Tokyo in November 1943. But as the war became more desperate, Japan announced in September 1944 that not only Java but the entire archipelago would become independent. This announcement was a tremendous vindication of the seemingly collaborative policies of Sukarno and Hatta. In March 1945, the Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Indonesian Independence (BPUPKI) was organized, and delegates came not only from Java but also from Sumatra and the eastern archipelago to decide the constitution of the new state. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The committee wanted the new nation's territory to include not only the Netherlands Indies but also Portuguese Timor and British North Borneo and the Malay Peninsula. Thus the basis for a postwar Greater Indonesia (Indonesia Raya) policy, pursued by Sukarno in the 1950s and 1960s, was established. The policy also provided for a strong presidency. Sukarno's advocacy of a unitary, secular state, however, collided with Muslim aspirations. An agreement, known as the Jakarta Charter, was reached in which the state was based on belief in one God and required Muslims to follow the sharia (in Indonesian, syariah — Islamic law). The Jakarta Charter was a compromise in which key Muslim leaders offered to give national independence precedence over their desire to shape the kind of state that was to come into being. Muslim leaders later viewed this compromise as a great sacrifice on their part for the national good and it became a point of contention, since many of them thought it had not been intended as a permanent compromise. The committee chose Sukarno, who favored a unitary state, and Hatta, who wanted a federal system, as president and vice president, respectively — an association of two very different leaders that had survived the Japanese occupation and would continue until 1956. *

On June 1, 1945, Sukarno gave a speech outlining the Pancasila; the five guiding principles of the Indonesian nation. Much as he had used the concept of Marhaenism to create a common denominator for the masses in the 1930s, so he used the Pancasila concept to provide a basis for a unified, independent state. The five principles are belief in God, humanitarianism, national unity, democracy, and social justice. *

On August 15, 1945, Japan surrendered. The Indonesian leadership, pressured by radical youth groups (the pemuda), were obliged to move quickly. With the cooperation of individual Japanese navy and army officers (others feared reprisals from the Allies or were not sympathetic to the Indonesian cause), Sukarno and Hatta formally declared the nation's independence on August 17 at the former's residence in Jakarta, raised the red and white national flag, and sang the new nation's national anthem, Indonesia Raya (Greater Indonesia). The following day a new constitution was promulgated. *

Political Positioning in Indonesia as World War II Ends

In September 1944—after U.S. forces occupied the town of Hollandia (now called Jayapura) in Papua and Australian troops landed on Morotai, Halmahera (Maluku) and Allied planes bombed Jakarta— Japan’s new prime minister, Koiso Kuniaki, announced on September 7, 1944, that the Indies (which he did not define) would be prepared for independence “in the near future,” a statement that appeared at last to vindicate Sukarno’s cooperative policies. Occupation authorities were instructed to further encourage nationalist sentiments in order to calm public restlessness and to retain the loyalty of cooperating nationalist leaders and their followers. Their response was comparatively slow, but spurred perhaps by evidence of growing anti-Japanese sentiment—in mid-February 1945, for example, a Peta unit in Blitar (eastern Java) revolted—the authorities on Java announced on March 1, 1945, their intention to form the Commission to Investigate Preparatory Measures for Independence (BPUPK); the term “Indonesia” was initially not used. Its membership—54 Indonesians, four Chinese, one Arab, and one Eurasian, plus eight Japanese “special members”—was announced on April 29. Meetings began on May 28. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The BPUPK took up questions such as the philosophy, territory, and structure of the state. Sukarno’s speech on June 1 laid out what he called the Pancasila or Five Principles, which were acclaimed as the philosophical basis of an independent Indonesia. In the original formulation, true to Sukarno’s prewar thinking, national unity came first, and while religion (“belief in a One and Supreme God”) was recognized in the fifth principle, one religion was pointedly not favored over another, and the state would be neither secular nor theocratic in nature. Thirty-nine of 60 voting members of the BPUPK voted to define the new state as comprising the former Netherlands East Indies as well as Portuguese Timor, New Guinea, and British territories on Borneo and the Malay Peninsula. Spirited debate on the structure of the state led finally to the acceptance of a unitary republic. An informal subcommittee, in a decision subsequently dubbed the Piagam Jakarta (Jakarta Charter), suggested that Muslim concerns about the role of Islam in the new state be addressed by placing Sukarno’s last principle first, requiring that the head of state be a Muslim, and adding a phrase requiring all Muslim citizens to follow the sharia. This declaration was to be the source of continuing misunderstanding. *

The United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, on August 6 and 8, 1945, and the Japanese rushed to prepare Indonesian independence. Vetoing the “Greater Indonesia” idea, military authorities required that the new state be limited to the former Netherlands East Indies and called for the establishment of an Indonesian Independence Preparatory Committee (PPKI) with Sukarno as chairman. This group was established on August 12, 1945, but Japan surrendered three days later, before it had an opportunity to meet. The established Indonesian leadership, led by Sukarno and Hatta, greeted the surrender with initial disbelief and caution, but some “pemuda”, many of them followers of Sutan Syahrir, took a more radical stance, kidnapping Sukarno and Hatta on the night of August 15–16 in an effort to force them to declare independence immediately and without Japanese permission. Their efforts may actually have delayed matters slightly, as Hatta later accused, but in any case, in a simple 'out as quickly and thoroughly as possible.” *

The next day, the PPKI met for the first time to adopt a constitution. Some key stipulations of the Jakarta Charter were cancelled, with the suggestion that such issues be revisited later, but the version of Pancasila that now became the official creed of the Republic of Indonesia began with the principle of “belief in [one supreme] God,” followed by humanitarianism, national unity, popular sovereignty arrived at through deliberation and representative or consultative democracy, and social justice. Such was the idealistic vision of a national civic society with which Indonesia began its independent life. *

Mohammed Hatta and Minangkabau Sutan Syahrir

Mohammed Hatta (1902-1980) is regarded along with Sukarno as one of the founders of Indonesia. Born in Sumatra, he was a tough, well-respected Muslim leader who served as vice president and prime minister of Indonesia after independence. He is credited with recognizing the inherent problems in making Indonesia an Islamic state and was opposed implementing Islamic law.

Minangkabau Sutan Syahrir Sjahrir (1909-66) was another important figure in the independence movement. He was a leading nationalist leader in Java and opposed Sukarno. Syahrir and Hatta were Sukarno's most important political rivals. Graduates of Dutch universities, they were social democrats in outlook and more rational in their political style than Sukarno, whom they criticized for his romanticism and preoccupation with rousing the masses. In December 1931 they established a group officially called Indonesian National Education (PNI-Baru) but often taken to mean New PNI. The use of the term "education" reflected Hatta's gradualist, cadre-driven education process to expand political consciousness. *

In 1927–28 Hatta and several other Perhimpunan Indonesia members were arrested in the Netherlands and charged with fomenting armed rebellion, but acquitted. Hatta and Syahrir were arrested in 1934 and sent to Boven Digul, and two years later to Banda Neira, Maluku, also for the remainder of Dutch rule. They were freed by the Japanese when they took over Indonesia in 1942. Sukarno and Hatta agreed in 1942 to cooperate with the Japanese, as this seemed to be the best opportunity to secure independence. Syahrir refused to cooperate with the wartime Japanese regime and had campaigned hard against retaining occupation-era institutions after the Japanese left.

See Separate Article on Sukarno:

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

Indonesia’s Precarious Position After World War II

The Indonesian republic's prospects were highly uncertain. The Dutch, determined to reoccupy their colony, castigated Sukarno and Hatta as collaborators with the Japanese and the Republic of Indonesia as a creation of Japanese fascism. But the Netherlands, devastated by the Nazi occupation, lacked the resources to reassert its authority. The archipelago came under the jurisdiction of Admiral Earl Louis Mountbatten, the supreme Allied commander in Southeast Asia. Because of Indonesia's distance from the main theaters of war, Allied troops, mostly from the British Commonwealth of Nations, did not land on Java until late September. Japanese troops stationed in the islands were told to maintain law and order. Their role in the early stages of the republican revolution was ambiguous: on the one hand, sometimes they cooperated with the Allies and attempted to curb republican activities; on the other hand, some Japanese commanders, usually under duress, turned over arms to the republicans, and the armed forces established under Japanese auspices became an important part of postwar anti-Dutch resistance. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The Allies had no consistent policy concerning Indonesia's future apart from the vague hope that the republicans and Dutch could be induced to negotiate peacefully. Their immediate goal in bringing troops to the islands was to disarm and repatriate the Japanese and liberate Europeans held in internment camps. Most Indonesians, however, believed that the Allied goal was the restoration of Dutch rule. Thus, in the weeks between the August 17 declaration of independence and the first Allied landings, republican leaders hastily consolidated their political power. Because there was no time for nationwide elections, the Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Indonesian Independence transformed itself into the Central Indonesian National Committee (KNIP), with 135 members. KNIP appointed governors for each of the eight provinces into which it had divided the archipelago. Republican governments on Java retained the personnel and apparatus of the wartime Java Hokokai, a body established during the occupation that organized mass support for Japanese policies. *

The situation in local areas was extremely complex. Among the few generalizations that can be made is that local populations generally perceived the situation as a revolutionary one and overthrew or at least seriously threatened local elites who had, for the most part, collaborated with both the Japanese and the Dutch. Activist young people, the pemuda, played a central role in these activities. As law and order broke down, it was often difficult to distinguish revolutionary from outlaw activities. Old social cleavages — between nominal and committed Muslims, linguistic and ethnic groups, and social classes in both rural and urban areas — were accentuated. Republican leaders in local areas desperately struggled to survive Dutch onslaughts, separatist tendencies, and leftist insurgencies. Reactions to Dutch attempts to reassert their authority were largely negative, and few wanted a return to the old colonial order. *

Establishment of the Indonesian Republic Immediately After World War II

As the war ended, Sukarno and Hatta were by far the most popular nationalist leaders. In August 1945 they were kidnapped and pressured by radical pemuda (youth groups) to declare independence before the Dutch could return. On August 17, 1945, with tacit Japanese backing, Sukarno proclaimed the independence of the Republic of Indonesia, from his Jakarta home. Indonesians rejoiced, but the Netherlands refused to accept the proclamation and still claimed sovereignty over Indonesia. British troops entered Java weeks later 1945 to accept the surrender of the Japanese. Under British auspices, Dutch troops gradually returned to Indonesia and it became obvious that independence would have to be fought for. [Source: Lonely Planet]

The new Republic’s prospects were at best uncertain. The war had ended very suddenly, and the Dutch—themselves only recently freed from Nazi rule—were unable to reestablish colonial authority, a task that in Sumatra and Java fell to British and British Indian troops, the first of which did not arrive until September 29, 1945. In the interval of nearly six weeks, the Republic of Indonesia was able to disarm a great many Japanese troops and form a government with Sukarno as president and Hatta as vice president. The Central National Committee (KNIP) was established as the principal decision-making body. It had regional and local subcommittees, based largely on the structure and personnel of the Jawa Hōkōkai. A comparatively smooth transition to an Indonesian-controlled bureaucracy and civil service took place in most areas, especially of Java. Australian troops continued occupying the eastern archipelago in late 1944 and, in 1945, accompanied by Dutch military and civilian personnel of the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (NICA), which had formed in Australia during the war. [Source: Library of Congress]

Violence in British-Controlled Indonesia Soon After World War II

Fighting broke out between the British and soldiers and militias with ties to the new Indonesian Republic after the British arrived beginning in September 1945. Things became particularly nasty in Surabaya after British Indian troops lander there and the leader of the British forces, General Mallaby, was killed by a bomb. The British launched bloody retaliatory attack, including air strikes, to take Surabaya on November 10 (now celebrated as Heroes Day). Fighting around Surabaya lasted for three weeks, leaving perhaps thousands of Indonesians dead. Tens of thousands fled to the countryside. Despite being poorly armed and trained, the Republican Army held their own, The brutality of the British offensive and the spirted defense helped unite the Indonesians and turn world opinion against colonialism in Indonesia.

Allied commander Earl Louis Mountbatten (1900–79) was charged with keeping the peace until his own troops could arrive and releasing Europeans who had been imprisoned by the Japanese and helping them resume their lives. Radical “pemuda”initiated, and encouraged others to take part in, violence against all those—not only Dutch and Eurasians but also Chinese and fellow Indonesians—who might be suspected of opposing independence. Sukarno’s government was powerless to stop this bloodletting, which by the end of September was well underway on Java. It grew in intensity and spread to deadly attacks on local elites as Allied troops moved to secure the main cities of Java and Sumatra. This sort of violence did not endear the Revolution to the outside world or, for that matter, to many Indonesians, but at the same time it was clear that closely allied to it was a fierce determination to defend independence. [Source: Library of Congress *]

When Allied troops landed in Surabaya in East Java in late October 1945, their plans to occupy the city were thwarted by tens of thousands of armed Indonesians and crowds of city residents mobilized by “pemuda”. On October 28, 1945, major violence erupted in Surabaya as occupying British troops clashed with pemuda (youth groups) and other armed groups. Following a major military disaster for the British in which their commander, A.W.S. Mallaby, and hundreds of troops were killed, the British launched a ferocious counterattack. The counterattack that began on November 10, enshrined in Indonesian nationalist history as Heroes’ Day, is estimated to have killed 6,000 Indonesians and others. The Battle of Surabaya (November 10-24) was the bloodiest single engagement of the struggle for independence. It forced the Allies to come to terms with the republic and convinced the British that they must plan for eventual withdrawal. A year later, the British turned military affairs over to the Dutch, who were determined to restore their rule throughout the archipelago. *

Dutch Return to Indonesia After World War II

In general, the Dutch view in late 1945 had been that the Republic of Indonesia was a sham, controlled largely by those who had collaborated with the Japanese, with no legitimacy whatsoever. A year later, this outlook had been modified somewhat, but only to concede that nationalist sentiment was more widespread than they had at first allowed; the complaint grew that, whatever its nature, the Republic could not control its violent supporters (especially “pemuda”and communists), making it unfit to rule. The newly formed United Nations formed a commission to settle the dispute. In 1946, the British left and the Dutch arrived and the Dutch and Indonesians signed a agreement calling for the gradual hangover transition from colonialism to self rule but fighting continued for three more years until 1949. [Source: Library of Congress *]

According to Lonely Planet: “The Dutch dream of easy reoccupation was shattered, while the British were keen to extricate themselves from military action and broker a peace agreement. The last British troops left in November 1946, by which time 55,000 Dutch troops had landed in Java. Indonesian Republican officials were imprisoned, and bombing raids on Palembang and Medan in Sumatra prepared the way for the Dutch occupation of these cities. In southern Sulawesi, Dutch Captain Westerling was accused of pacifying the region – by murdering 40,000 Indonesians in a few weeks. Elsewhere, the Dutch were attempting to form puppet states among the more amenable ethnic groups.” [Source: Lonely Planet]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025