INDONESIAN “COUP” IN SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 1965

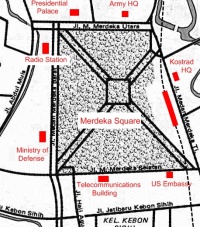

On September 30 and the wee hours of October 1, 1965, a faction of young officers in Jakarta, launched a so called coup by kidnapping and assassinating six top generals, including Army Chief of Staf Yan. Their bodies were dumped in a well near Jakarta’s air force base. The only general earmarked for assassination that escaped was Gen. Abdul Haris Nasution. He survived by famously leaping over a wall—while dodging bullets— from his house into the Iraqi ambassador’s house next door. His 6-year-old daughter wasn’t so lucky. She was left behind and shot to death.

In the early morning hours of October 1, 1965, troops from four ABRI companies, including one from the Cakrabirawa Presidential Guard, deployed in air force motor vehicles through the streets of Jakarta to the homes of Nasution, Yani, and five other generals known to be opposed to the Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI), at that time the largest Communist party outside the Soviet Union and China.. Three were killed resisting capture, and three were later murdered at the nearby Halim Perdanakusuma Military Air Base, where, it was later learned, their bodies were thrown into an abandoned well in an area known as Lubang Buaya (Crocodile Hole). The remaining general, then-Minister of Defense Nasution, narrowly escaped, but his adjutant was captured instead and also murdered at Lubang Buaya, and Nasution’s daughter was injured in the intrusion and later died.

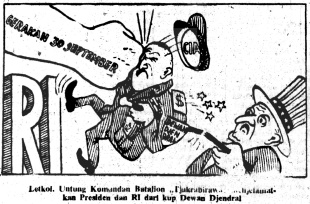

Not long afterwards, Jakartans awoke to a radio announcement that the September 30 Movement (Gerakan September Tiga Puluh, later referred to by the acronym Gestapu by opponents) had acted to protect Sukarno and the nation from corrupt military officers, members of a Council of Generals that secretly planned, with U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) help, to take over the government. The announcement stressed that the action was an internal ABRI affair. At noon a Decree No. 1 was broadcast, announcing the formation of a Revolutionary Council as the source of all authority in the Republic of Indonesia.

RELATED ARTICLES:

VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: KILLERS, VICTIMS, REASONS factsanddetails.com

LEGACY OF THE VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: FEAR, FILMS AND LACK OF INVESTIGATION factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO: HIS LIFE, PERSONALITY AND RISE TO POWER factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO AS PRESIDENT: CHALLENGES, AUTHORITARIANISM, GUIDED DEMOCRACY factsanddetails.com

DIFFICULTY MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK IN INDONESIA IN THE 1950s factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA DECLARES INDEPENDENCE IN 1945 AT THE END OF WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA’S NATIONAL REVOLUTION: THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE 1945-1949 factsanddetails.com

INDONESIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE (1945-1949): POLICE ACTION, ATROCITIES, MASSACRES factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA OFFICIALLY ACHIEVES INDEPENDENCE factsanddetails.com

1965 Coup Collapses

Led by one Colonel Untung of the palace guards, the rebels seized the national radio station and took up positions around the presidential palace. The effort was ill-conceived and poorly executed and had little support from within the army let alone the nation as a whole. The group behind the coup claimed they had acted as they did to foil a plot organized by the generals to overthrow the president. [Source: Lonely Planet]

The “coup” is often called the “September 30 Movement.” It ended a few hours after it began when Suharto— then head of the army’s Strategic Reserve and the only senior general not targeted — took control of the army, crushed the rebellion and used it as an excuse to seize power and oust Sukarno, who was accused of being too close to the Communists. Suharto became the leader of the military and the effective leader of the country.

The exact circumstances have never been fully explained. Newspapers and radio broadcasts claimed that the generals had been tortured and mutilated by a communist women’s organization. Although autopsies later ordered by General Suharto refuted these claims, the sensational stories had already spread rapidly. There were also reports that Indonesian President Sukarno may have had advance knowledge of the coup.

Weak and Divisive Sukarno in the Early 1960s

Ultimately, government of Indonesian President Sukarno could not sustain the deep divisions that had taken hold of Indonesian society. Polarization and mutual suspicion intensified between non-communist forces—led by elements of the military and supported by several Muslim groups—and the Communists, dominated by the PKI. Their rivalry pushed the country steadily toward confrontation and violence.

The broader international environment added further instability. Sukarno denounced the Western powers, waged a low-intensity conflict against Malaysia, and increasingly aligned Indonesia with the People’s Republic of China. At home, he tried to keep a sense of “permanent revolution” alive. Civil servants were required to publicly pledge loyalty to his political campaigns and repeat his slogans. Meanwhile, economic management was neglected: by 1965 inflation had soared above 650 percent, and poverty and hunger had become widespread.

Sukarno was worried about the military, which had been developing close links with the Pentagon, and he sought to establish a counterweight by strengthening the PKI. By 1965, the PKI controlled many of the mass civic and cultural organizations that Sukarno had established to mobilize support for his regime and, with Sukarno's acquiescence, embarked on a campaign to establish a “Fifth Column” by arming its supporters. Army leaders resisted this campaign. [Source: Pankaj Mishra, The New Yorker, August 4, 2014]

Sukarno’s health also deteriorated during these years, and many in Jakarta sensed that he was losing control. The 1963 eruption of Mount Agung in Bali was even interpreted by some as an omen of his weakening authority.

Rising communist activism and regional uprisings in central and eastern Java eventually converged in the 30 September Movement, led by Lt. Col. Untung. By this time Sukarno’s foreign policy had tilted sharply toward Communist China, further heightening tensions within the fractured political landscape.

Events Before the 1965 Coup

Tensions under Sukarno rule had escalated by late 1964 to the point that government was paralyzed and the nation seethed with fears and rumors of an impending explosion. In the countryside, especially in Java and Bali, the “unilateral actions” the PKI began a year earlier to forcefully redistribute village agricultural lands had resulted in the outbreak of violence along both religious and economic class lines. Especially in Jawa Timur Province, Nahdlatul Ulama mobilized its youth wing, known as Ansor (Helpers of Muhammad), and deadly fighting began to spread between and within now thoroughly polarized villages. ABRI increasingly revealed divisions among pro-PKI, anti-PKI, and pro-Sukarno officers, some of whom reportedly began to involve themselves in rural conflicts. In the big cities, demonstrations against the West reached fever pitch, spilling over into intellectual and cultural affairs as poets and artists confronted each other with diametrically opposed views on the nature and proper social role of the arts. The domestic economic crisis deepened as the price of rice soared beyond the means of most urban residents, especially those of the middle classes on government salaries, and the black-market rate of exchange exceeded the official rate by 2,000 percent. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Sukarno was furious that the newly formed Malaysia had been granted a temporary seat on the United Nations Security Council, and on January 1, 1965, he withdrew Indonesia from the UN, and later from other world bodies such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. In April, China announced that it supported the idea, proposed earlier by Aidit, of arming a “fifth force” of peasants and workers under PKI leadership to balance the power of ABRI’s four armed services, and that it could supply 100,000 small arms for the purpose. Then on August 17, 1965, Sukarno, who two weeks earlier had collapsed during a public appearance and was thought to be gravely ill, delivered an Independence Day speech, which addressed joining a “Jakarta–Phnom Penh–Beijing–Hanoi– Pyongyang Axis” and creating an armed fifth force in order to complete Indonesia’s revolution. It seemed to many that the PKI was poised to seize power, at the same time that the whole constellation of competing forces swirling around Sukarno was about to implode, with consequences that could only be guessed. *

On September 27, the army chief of staff, Ahmad Yani (1922–65), who was close to Sukarno and shared his anti-neo-imperialist outlook, nevertheless informed him that he and Nasution unequivocally refused to accept a “fifth force,” a stand that brought them in direct opposition to the PKI, Sukarno, and even some ABRI officers. Air Force Vice Marshal Omar Dhani (1924–2009), for example, had begun to offer paramilitary training to groups of PKI civilians, apparently at Sukarno’s urging. The balancing act was over. *

Impact of the September 1965 “Coup”

Joe Cochrane wrote in the New York Times, “The purge’s victims were branded as Communist Party members and sympathizers, but they included intellectuals and ethnic Chinese, a mistrusted minority, and were killed by soldiers as well as by civilian, paramilitary and religious groups backed by the Indonesian military. Many of the victims were spirited away in the night and never seen again. Hundreds of thousands more were arrested and held in detention centers for years, and the surviving families of Communist Party members and suspected supporters were shunned. [Source: Joe Cochrane, New York Times, March 1, 2014]

History books refer to the event as an "attempted communist coup" and the officers were referred to as sympathizers of the Communist Party but their no evidence that Communist Party of Indonesia was involved in the coup. The Indonesia novelist Pramoedya Ananta Toer wrote in Time: "The communists had 3 million members and supporters at that time. If they wanted to launch a coup, why didn't they just mobilize their branches in cities and towns outside Jakarta. Why was the party leadership caught completely off guard by the kidnapping?”

These momentous events, which triggered not only a regime change but also the destruction of the largest communist party outside the Soviet Union and China, hundreds of thousands of deaths, and a generation of military rule in what was then the world’s fifth (now fourth) most populous country, have long eluded satisfactory explanation by scholars. Debate over many points, both in and outside of Indonesia, continues to be stubborn, polarized, and dominated by intricate and often improbable tales of intrigue. The circumstances and available data are such that a wide variety of explanations are equally plausible. Scholarly opinion has been especially skeptical of the conclusion drawn almost immediately by Suharto (and later the government he headed) and the CIA, that the PKI was to blame for Gestapu. Experts have offered numerous scenarios instead, suggesting that the (anti-PKI) military, and perhaps even Suharto himself, were in fact the real masterminds.

Who Was Behind the 1965 Coup?

There is some debate as to whom led the “coup” and why. Many of the details of what really happened during the coup remain a mystery and many important details revolve around what Suharto knew and when he knew it. The former colonel who led the coup told reporters after he was released form jail in 1998 he "reported the scheme to Mr.Suharto in advance."

Some think the September 1965 attempted coup was orchestrated by lower ranking military officers jealous of the privileges enjoyed by senior generals. Others have said it was masterminded by the PKI (Communists) which had heavily infiltrated the army. Some say Suharto himself was behind it. Suharto was a staunch anti-Communist. "The coup was Suharto's...Suharto needed the slaughter to instill fear in everyone." The night before the coup, Suharto met with the leader of the Communist Revolutionary Council, Abu Latief. What was said during that meeting is still a secret. Latief was still in a Jakarta jail when Suharto resigned in 1998.

Some have suggested that the coup was engineered by the United States and Britain to place blame on the Communists and allow for Suharto, who would turn out to be more friendly towards the West than Sukarno, to take power. Other have suggested that Sukarno participated in it to get rid of the threatening generals.

The extent and nature of PKI involvement in the coup are unclear. The Indonesian army claimed that the PKI plotted the coup and used disgruntled army officers to carry it out. Civilians from the PKI’s People’s Youth organisation accompanied the army battalions that seized the generals, but some claim this was a set up. Whereas the official accounts promulgated by the military describe the communists as having a "puppetmaster" role, some foreign scholars have suggested that PKI involvement was minimal and that the coup was the result of rivalry between military factions.

Although evidence presented at trials of coup leaders by the military implicated the PKI, the testimony of witnesses may have been coerced. A pivotal figure seems to have been Syam, head of the PKI's secret operations, who was close to Aidit and allegedly had fostered close contacts with dissident elements within the military. But one scholar has suggested that Syam may have been an army agent provocateur who deceived the communist leadership into believing that sympathetic elements in the ranks were strong enough to conduct a successful bid for power. Another hypothesis is that Aidit and PKI leaders then in Beijing had seriously miscalculated Sukarno's medical problems and moved to consolidate their support in the military. Others believe that ironically Sukarno himself was responsible for masterminding the coup with the cooperation of the PKI. [Source: Library of Congress *]

In a series of papers written after the coup and published in 1971, Cornell University scholars Benedict R.O'G. Anderson and Ruth T. McVey argued that it was an "internal army affair" and that the PKI was not involved. There was, they argued, no reason for the PKI to attempt to overthrow the regime when it had been steadily gaining power on the local level. More radical scenarios allege significant United States involvement. United States military assistance programs to Indonesia were substantial even during the Guided Democracy period and allegedly were designed to establish a pro-United States, anticommunist constituency within the armed forces. *

More recently, however, a view that has gained credence (originally posited in an early CIA report and raised by captured PKI leaders) is that Gestapu was in fact the result of highly secret planning— secret even within the PKI leadership structure—by party head D. N. Aidit and his close friend since pemuda days in 1945, “Syam” Kamaruzaman (ca. 1924–86), head of the party’s supersecret Special Bureau. For reasons that are not entirely clear but were probably connected with Aidit’s fears that Sukarno was near death and that without his protection the party could not survive, Syam was given responsibility for constructing a plot to neutralize army opposition. It is generally acknowledged that the plans were ill-conceived and so poorly executed that investigators often found comparatively simple errors unbelievable, taking them instead as clues to hidden conspiracies. The movement collapsed almost instantaneously, more from its own weaknesses than as a result of any brilliance or preparation that might be ascribed to Suharto’s response. *

Countercoup and Suharto’s Takeover of the Indonesian Government

After the September 1965 attempted coup Suharto orchestrated a counter-coup and an anti-communist purge that embraced the whole of Indonesia. Hundreds of thousands of communists and their sympathisers were slaughtered or imprisoned, primarily in Java and Bali. The party and its affiliates were banned and its leaders were killed, imprisoned or went into hiding. [Source: Lonely Planet]

On October 1 1965, faced with the news of this apparent coup attempt, Suharto, the commander of the Army Strategic Reserve Command (Kostrad), who had not been on the list of those to be captured, moved swiftly, and, less than 24 hours after events began, a radio broadcast announced that Suharto had taken temporary leadership of ABRI, controlled central Jakarta, and would crush what he described as a counterrevolutionary movement that had kidnapped six generals of the republic. (Their bodies were not discovered until October 3.) When the communist daily Harian Rakjat published an editorial supportive of the Revolutionary Council on October 2, 1965, it was already too late. In Jakarta, the coup attempt had been broken, and anti-PKI, anti-Sukarno commanders of ABRI were in charge. Within a few days, the same was true of the few areas outside of the capital where Gestapu had raised its head.

The period from October 1965 to March 1966 witnessed the eclipse of Sukarno and the rise of Suharto to a position of supreme power. After the elimination of the PKI and purge of the armed forces of pro-Sukarno elements, the president was left in an isolated, defenseless position. By signing the executive order of March 11, 1966, Supersemar, he was obliged to transfer supreme authority to Suharto. On March 12, 1967, the MPRS stripped Sukarno of all political power and installed Suharto as acting president. Sukarno was kept under virtual house arrest, a lonely and tragic figure, until his death in June 1970. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The year 1966 marked the beginning of dramatic changes in Indonesian foreign policy. Friendly relations were restored with Western countries, Confrontation with Malaysia ended on August 11, and in September Indonesia rejoined the UN. In 1967 ties with Beijing were, in the words of Indonesian minister of foreign affairs Adam Malik, "frozen." This meant that although relations with Beijing were suspended, Jakarta did not seek to establish relations with the Republic of China on Taiwan. That same year, Indonesia joined Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Singapore to form a new regional and officially nonaligned grouping, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which was friendly to the West. *

Removal of Sukarno From Power After the September 1965 Coup

Throughout the period from 1965 to 1966, President Sukarno vainly attempted to restore his political stature and return the country to its position prior to October 1965. By mid-October 1965, the army, under the command of Gen. Suharto, was in virtual control of the country. On March 12, 1966, following nearly three weeks of student riots, President Sukarno transferred to Suharto the authority to take, in the president's name, "all measures required for the safekeeping and stability of the government administration."

The abrupt narrative break of the violent events that immediately followed the 1965 coup gives the impression that the transition from the Old Order to the New Order (as they came to be called, first by anti-PKI, anti-Sukarno student protesters) was swift. In reality, Sukarno’s power and Guided Democracy policies dissolved more slowly, despite fierce opposition in some circles to his continued defense of the PKI and his refusal to concede that Guided Democracy had failed. Suharto and his supporters were aware that Sukarno continued to have loyal followers, and they did not wish to risk more upheaval, much less a backlash against the army. Military tribunals began holding well-managed trials of PKI figures, and a gradual removal began of ABRI officers and troops thought to be strong PKI or Sukarno loyalists. [Source: Library of Congress *]

In early 1966, Sukarno, still the acknowledged president, was pressured into signing the Letter of Instruction of March 11 (Surat Perintah Sebelas Maret, later known by the acronym Supersemar), turning over to Suharto his executive authority, for among other reasons, to keep law and order and to safeguard the Revolution. The next day, the PKI was officially banned and its surviving leaders, as well as prominent pro-Sukarno figures, arrested and imprisoned. Over the next few months, the new government largely dismantled Sukarno’s foreign policy as Jakarta broke its ties with Beijing, abandoned confrontation with Malaysia, rejoined the UN and other international bodies, and made overtures to the West, especially for economic assistance. The Inter-Governmental Group on Indonesia (IGGI) was formed to coordinate this aid. In mid-1966, the Provisional People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR(S)) demanded that Sukarno account for his behavior regarding Gestapu, but he stubbornly refused; only early the next year did he directly claim that he had known nothing in advance of those events. But by then, even many of his supporters had lost patience.

On March 12, 1967, the the Provisional People's Consultative Assembly (MPRS) formally removed Sukarno from power and appointed Suharto acting president in his stead. One year later, it conferred full presidential powers on Suharto, and he was sworn in as president for a five-year term. The congress also agreed to postpone the general elections due in 1968 until 1971. The New Order thus officially began as the Old Order withered away.

Alone and bitter, Sukarno lived under virtual house arrest in the presidential palace in Bogor, Jawa Barat Province, until his death in June 1970, and he was buried far from the nation’s capital in his home town of Blitar in Jawa Timur Province.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025