IMPACT OF THE CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66

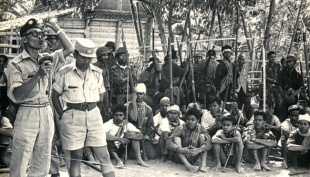

After a failed coup attempt in September and October 1965 in Jakarta blamed in part on Indonesian Communists there was a ruthless campaign of bloodletting mainly targeting Communists and suspecting leftists in which an estimated 300,000 to 1 million Indonesians were killed. Some Indonesians later took pride in the destruction of the Indonesian Communist Party, while many others recall the period with shame and horror. Historians have noted that the violence echoed patterns of coercion and force rooted in the colonial era—an intensification of longstanding forms of state and paramilitary brutality—but the scale and ferocity of the 1965–1966 killings remain a profound and unsettling tragedy in Indonesian history. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

The mass killings took place mostly between October 1965 and March 1966 and then in occasional outbursts for several years thereafter. Although there are no satisfactory data on which reliable national calculations can be made, and Indonesian government estimates have varied from 78,500 to 1 million killed. of the post-coup death toll vary widely. Adam Malik, who was to become Suharto’s foreign minister, said that a ‘fair figure’ was 160,000. A figure of approximately 500,000 deaths was accepted in the mid1970s by the head of the Operational Command for the Restoration of Security and Order (Kopkamtib) and is widely used in Western sources. [Source: Library of Congress]

The emotions and fears of instability created by the crisis persisted for many years, as the Communist Party remains banned in Indonesia. Joe Cochrane wrote in the New York Times, “The party was officially banned, and in an indication of how accepted the official state narrative remains... Schoolchildren are still taught that the Communists brought the violence upon themselves by plotting to take over the country. [Source: Joe Cochrane, New York Times, March 1, 2014]

RELATED ARTICLES:

COUP OF 1965 AND THE FALL OF SUKARNO AND RISE OF SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: KILLERS, VICTIMS, REASONS factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO: HIS LIFE, PERSONALITY AND RISE TO POWER factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO: HIS LIFE, CHARACTER AND IDEOLOGY factsanddetails.com

SUKARNO AS PRESIDENT: CHALLENGES, AUTHORITARIANISM, GUIDED DEMOCRACY factsanddetails.com

DIFFICULTY MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK IN INDONESIA IN THE 1950s factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA DECLARES INDEPENDENCE IN 1945 AT THE END OF WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA’S NATIONAL REVOLUTION: THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE 1945-1949 factsanddetails.com

INDONESIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE (1945-1949): POLICE ACTION, ATROCITIES, MASSACRES factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA OFFICIALLY ACHIEVES INDEPENDENCE factsanddetails.com

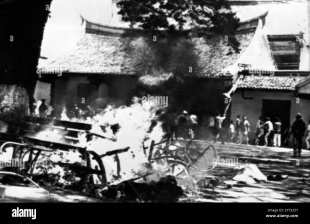

Students Sack the Chinese Embassy in Jakarta

In April 1966, the New York Herald Tribune reported: About 2,000 screaming Indonesian Chinese sacked the Chinese embassy here today [April 14], smashing doors and windows and lighting vast bonfires of documents in the latest outburst of anti-Peking feelings. With a truck, they battered down the 15-foot red gate guarding the building and, once inside, smashed three cars, ripped the Chinese crest off the chancery, tore down the flag and replaced it with the Indonesian standard. [Source:New York Herald Tribune, European Edition, April 16, 1966]

“The two-hour demonstration followed a rally at which the Chinese students pledged loyalty to Indonesia. They charged Peking with interfering in Indonesian affairs and called for a break in diplomatic relations. An Indonesian Army officer said embassy staff members fired on the demonstrators with machine guns, wounding three. Two others were hurt by tiles flung from roofs.

“The staff hurled bottles, stones and chairs at the students. Students found hundreds of small Chinese flags and used them to wipe sweat from their faces. More students moved into a provisions storeroom and began guzzling Chinese wine. *

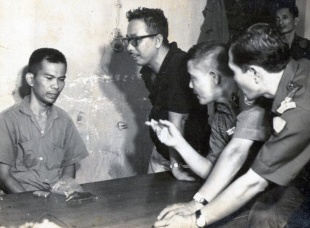

Perpetrators and Detainees After the 1965-66 Crackdown

Joe Cochrane wrote in the New York Times, The men starring in the film “The Act of Killing” essentially confess to mass murder but are viewed by many Indonesians as heroes for their service to the nation at a time when the Communists in Vietnam were gaining ground. In one of the most surreal scenes, the men — invited to depict their sentiments over their actions as they saw fit — danced to a rendition of “Born Free” in front of a waterfall. [Source: Joe Cochrane, New York Times, March 1, 2014]

According to the Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity: “Even after 1978, the regime continued to discriminate against former detainees and their families. Former detainees commonly had to report to the authorities at fixed intervals (providing opportunities for extortion). A certificate of non-involvement in the 1965 coup was required for government employment or employment in education, entertainment, or strategic industries. From the early 1990s, employees in these categories were required to be "environmentally clean," meaning that even family members of detainees born after 1965 were excluded from many jobs, and their children faced harassment in school. A ban on such people being elected to the legislature was lifted only in 2004. A ban on the teaching of Marxism-Leninism remains in place. [Source: Robert Cribb, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

Impact of America’s Role in the Violence of 1965-66

In 1965-6, the American government assisted the Indonesian government in the mass incarceration and murder of approximately one million of its citizens. But it’s role has largely been forgotten in the English-speaking world precisely because it was such a success. Vincent Bevins wrote in the , New York Times: No American soldiers died; little attention was drawn to one more country pulled, seemingly naturally, into the United States’ orbit. Recently declassified State Department documents make it clear that the United States aided and abetted the mass murder in Indonesia, providing material support, encouraging the killings and rewarding the perpetrators. [Source: Vincent Bevins, New York Times, May 29, 2020]

“It was not the first time the United States had done something like this. In 1954, the American ambassador to Guatemala reportedly handed kill lists to that country’s military. And in Iraq, in 1963, the C.I.A. provided lists of suspected communists and leftists to the ruling Baath Party.

“Indonesia in 1965 was the apex of anti-Communist violence in the 20th century. The slaughter obliterated the popular, unarmed Partai Komunis Indonesia, the largest Communist party outside of China and the Soviet Union, and toppled President Sukarno, a founding leader of the Nonaligned Movement and an outspoken anti-imperialist, replacing him with General Suharto, a right-wing dictator who quickly became one of Washington’s most important Cold War allies.

“This was such an obvious victory for the global anti-Communist movement that far-right groups around the world began to draw inspiration from the “Jakarta” model and build copycat programs. They were assisted by American officials and anti-Communist organizations that moved across borders. In turn, leftist movements radicalized or took up arms, believing they would be killed if they attempted to pursue the path of democratic socialism.

“In the early ’70s, right-wing terrorists in Chile painted “Jakarta” on the houses of socialists, threatening that they too would be killed. After the C.I.A.-backed coup in 1973, they were. Brazilian leftists were threatened with “Operação Jacarta,” too. By the end of the 1970s, most of South America was governed by authoritarian, pro-American governments that secured power by mass murder. By 1990, death squads in Central America pushed the Latin American death toll into the hundreds of thousands.

Failure to Fully Investigate the Violence After the September 1965 Coup

Robert Cribb wrote in the Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity: “Remarkably few accounts of the killings were written at the time, and the long era of military-dominated government that followed in Indonesia militated against further reporting. The destruction of the PKI was greeted enthusiastically by the West, with Time magazine describing it as "The West's best news for years in Asia," and there was no international pressure on the military to halt or limit the killings. After the fall of Suharto in 1998, there was some attempt to begin investigation of the massacres, but these efforts were hampered by continuing official and unofficial anticommunism and by the pressure to investigate more recent human rights abuses. President Abdurrahman Wahid (1999–2001) apologized for the killings on behalf of his orthodox Muslim association, Nahdlatul Ulama, but many Indonesians continued to regard the massacres as warranted. As a result, much remains unknown about the killings.[Source: Robert Cribb, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

Although scholars and journalists have long examined the 1965–66 mass killings, communism remains a deeply sensitive issue in Indonesia. Public discussions are still vulnerable to suppression, as seen when police shut down a forum on Tan Malaka after protests from a hard-line Islamic group. Efforts at official accountability have also stalled. Indonesia’s National Commission on Human Rights concluded in 2012 that the purges were gross human rights violations involving rape, torture, and mass executions carried out by the military and its civilian allies, and it called for a criminal investigation. [Source: Joe Cochrane, New York Times, March 1, 2014]

The attorney general’s office has repeatedly refused to act, reportedly to avoid embarrassing powerful institutions—including the armed forces and influential political, paramilitary, and religious groups—many of which trace their prominence to roles in the purges. Senior commanders implicated in the killings, such as Sarwo Edhie Wibowo, remain politically sensitive figures; his daughter is married to former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. The attorney general’s office has returned the commission’s 850-page report multiple times for revisions, blocking progress despite renewed submissions.

In April 2016, Indonesia’s president, Joko Widodo, directed his government to investigate the mass killings of 1965–66, signaling a potential break from decades of official reluctance to confront the anti-Communist purges. His senior minister, Luhut B. Pandjaitan was instructed to collect information on alleged mass graves, though he publicly questioned whether such graves exist despite extensive evidence from human rights groups. Human rights organizations, including the Commission for Missing Persons and Victims of Violence, say they have documented numerous mass graves across Java, Bali, and Sulawesi. [Source: Jeffrey Hutton, New York Times, April 26, 2016]

"Act of Killing" and “Look of Silence”’: Films About the Violence 1965-66

For nearly a decade, American filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer investigated the mass killings of 1965–66 in Indonesia, speaking extensively with both survivors and perpetrators. His two landmark documentaries, “The Act of Killing” (2012) and “The Look of Silence” (2014), exposed a national history long shrouded in silence and impunity. [Source: Joe Cochrane, New York Times, March 1, 2014; Ann Hornaday, Washington Post, July 25, 2013; Al Jazeera, March 28, 2016]

The “Act of Killing” presents the genocide from the perspective of the killers, many of whom are still celebrated as heroes. Oppenheimer had former death-squad leaders openly describe their crimes and even stage imaginative reenactments modeled on the Hollywood genres they admired. The result, noted critics, is a chilling portrait of violence and its lingering aftermath—corruption, fear, and the normalization of brutality. The film drew global attention, earning dozens of awards and an Academy Award nomination.

Jonah Weiner wrote in The New Yorker: “Confronted with these men, Oppenheimer struck upon an audacious and bizarre storytelling device: he invited Congo and several of his fellow-executioners to make their own movie about the purge, telling the story through dramatic reënactments of their devising, in which they would portray not only themselves but also people they interrogated, tortured, and killed. The gusto with which Congo and his compatriots take to the project is jarring; this is grisly history as told by the victors. [Source: Jonah Weiner, The New Yorker, July 15, 2013]

The “Look of Silence” shifts focus to the victims. The film follows Adi Rukun, an optometrist born two years after his brother Ramli was murdered. Ramli’s killing was unusual in that it was witnessed—most victims were taken to rivers and disappeared. The Rukun family once faced military threats for attempting to speak about the crime. Oppenheimer explains that neither of his films is simply a historical record; both confront a present-day climate of fear in which perpetrators still live openly in communities that remember their actions.

Making “Act of Killing” and the Reaction in Indonesia to It

While living in London after studying film at Harvard and as a Marshall Scholar, Joshua Oppenheimer began developing experimental documentaries with former classmate Christine Cynn. Commissioned by the International Union of Food and Agricultural Workers to document labor struggles, they traveled to Indonesia to film women working on an oil-palm plantation. Oppenheimer, who at the time knew neither Indonesian nor the country’s history, soon learned that the workers’ greatest obstacle to unionizing was fear. Many of their parents and grandparents had been union members in the early 1960s and were later arrested as alleged communist sympathizers during Suharto’s rise to power. Oppenheimer discovered that many had been sent to military-run concentration camps and then handed over to civilian death squads to be executed—traumas that continued to haunt their descendants.

When Oppenheimer and Cynn returned to Indonesia, survivors urged them to interview the killers themselves. To their shock, these men—who proudly called themselves “gangsters”—still lived openly and boasted about their past violence, continuing to intimidate victims’ families. As Oppenheimer filmed them, his focus evolved from documenting what happened to understanding why the perpetrators glorified their crimes, how this boasting shaped society, and how the killers viewed themselves and wanted to be seen. Cynn eventually left the project, and Oppenheimer continued working with a mostly anonymous Indonesian crew, including his co-director.

“The Act of Killing” received a strong reception inside Indonesia. The magazine Tempo devoted an entire issue to the film and launched its own investigation, and in the first months after release, it was screened hundreds of times across dozens of cities. Oppenheimer planned to make it freely available for Indonesians online. Although international acclaim grew, including support from executive producers Werner Herzog and Errol Morris, Oppenheimer hoped the film would spark a national reckoning. Yet coverage within Indonesia remained limited; major television networks ignored its Oscar nomination, and only a few print outlets reported on it.

The topic remains deeply sensitive because elements of the military and elite who were involved in the 1965–66 killings continue to defend their actions as preventing a communist takeover. Fearing censorship, Oppenheimer did not attempt a commercial theatrical release in Indonesia. Still, the film circulated widely online, including tens of thousands of YouTube downloads in its first week. Oppenheimer argued that removing Suharto was only the first step: Indonesians still needed grassroots movements strong enough to hold democratic institutions accountable. But fear persisted. After publication of a newspaper article naming a youth organization involved in the killings, a mob attacked the newspaper’s offices and beat its editor. Senior officials also publicly rejected findings from Indonesia’s human rights commission, insisting the military had saved the nation.

The danger was serious enough that the Indonesian co-director and the roughly 60 local crew members credited themselves only as “Anonymous.” The co-director later explained that, despite democratic reforms since 1999, many military, political, and business figures from the Suharto era still held power—proof, he said, that “behind the facade, the machinery is still the same.” Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025