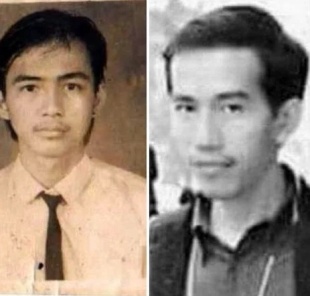

JOKO WIDODO

Joko Widodo widely known as Jokowi, is an Indonesian politician and former businessman who served as Indonesia’s seventh president from 2014 to 2024.Jokowi was born Mulyono on June 21, 1961 and raised in a riverside slum in Surakarta. He graduated from Gadjah Mada University in 1985 and married Iriana the following year.

Before entering politics, he worked as a carpenter and later as a furniture exporter. His tenure as mayor of Surakarta brought him national attention for pragmatic governance and hands-on leadership, leading to his election as governor of Jakarta in 2012 alongside Basuki Tjahaja Purnama as deputy governor. As governor, Jokowi popularized blusukan—unannounced inspections of neighborhoods and markets—streamlined the city bureaucracy, reduced corruption, expanded access to healthcare, addressed chronic flooding through river dredging, and launched the long-delayed Jakarta mass rapid transit project.

Joko Widodo was well-known for his charisma and fondness for the heavy metal band Metallica. Tom Pepinsky wrote in the Washington Post in 2014: “Part of what makes Jokowi so exciting to many Indonesians is his political story: even though he is the governor of Jakarta, he came to this position relatively” shortly before becoming president,” having made his political career as mayor of Solo, a smaller city in Central Java. Before that he was a local businessman. As mayor, Jokowi was widely credited for overseeing a range of local governance reforms in Solo, resisting corruption and streamlining the local business environment without alienating the masses (he won reelection with 90 percent of the vote in 2010). His folksy demeanor charms many Indonesians and foreigners alike, and he can be credibly portrayed as a relative outsider to national politics. [Source:Tom Pepinsky, Washington Post, March 17 2014]

RELATED ARTICLES:

2014 ELECTION IN INDONESIA: ROCK STARS, RALLIES AND SMEAR CAMPAIGNS factsanddetails.com

JOKO WIDODO AS PRESIDENT: HIS FOLKSY STYLE, ACHIEVEMENTS AND CRITICS factsanddetails.com

2024 ELECTIONS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

REFORMASI AND THE POST–SUHARTO ERA factsanddetails.com

MEGAWATI SUKARNOPURTI (PRESIDENT OF INDONESIA 2001-2004): LIFE, POLITICAL CAREER, FAILURES factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO: HIS LIFE, PERSONALITY AND RISE TO POWER factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER SUHARTO: NEW ORDER, DEVELOPMENT, FOREIGN POLICY factsanddetails.com

REPRESSION UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: KILLERS, VICTIMS, REASONS factsanddetails.com

CORRUPTION AND FAMILY WEALTH UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998: PRESSURES, EVENTS, RESIGNATION factsanddetails.com

INDONESIAN ELECTIONS IN 2004 AND 2009 factsanddetails.com

SUSILO BAMBANG YUDHOYONO (PRESIDENT OF INDONESIA 2004-2014): LIFE, CAREER, INTERESTS factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER YUDHOYONO (2004-2014) factsanddetails.com

Joko Widodo’s Early Life

Joko Widodo was born Mulyono on June 21, 1961 at Brayat Minulya General Hospital in Surakarta, also known as Solo, a busy regional city at the heart of Javanese culture.. Of Javanese heritage, he is the only son of Widjiatno Notomihardjo and Sudjiatmi and the eldest of four children. His father hailed from Karanganyar, while his grandparents were from a village in Boyolali. Jokowi has three younger sisters: Iit Sriyantini, Idayati, and Titik Relawati. His working-class family lived in illegally built shacks along a river. His father was a wood seller and furniture maker. [Source: Wikipedia, Associated Press]

As a child, he was frequently ill, and in accordance with Javanese custom his name was changed to Joko Widodo, with widodo meaning “healthy.” From the age of 12, he worked in his father’s furniture workshop. During his youth, the family lived in three rented homes—one later declared unfit for habitation by the government—experiences that shaped his views on housing and urban poverty. These early influences later informed his efforts to expand low-income housing during his tenure as mayor of Surakarta.

The dwelling that Widodo grew up in was flood-prone riverside squat on the banks of the Anyar river with a large family sleeping in one room and walls made of woven bamboo. "His parents couldn't afford to buy a house of their own, so the family kept moving from one rented house to another, all built illegally on government land," says Jokowi's biographer Yon Thayrun. [Source: Michael Bachelard, Sydney Morning Herald, June 14 2014]

Michael Bachelard wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald: His father, Noto Mihardjo, scraped a living as a wood seller and the skinny boy helped in the afternoons after school, collecting and cutting logs...A former neighbour of Jokowi, Suharno, still lives by the river. He remembers young Joko fondly, telling of a serious child who was traumatised in the 1970s when their squat was cleared by the government to make way for a truck depot. Joko consoled himself with reading and heavy metal. [Source: Michael Bachelard, Sydney Morning Herald, June 14 2014]

Joko Widodo’s Education

Jokowi attended State Elementary School 111 Tirtoyoso and State Junior High School 1 Surakarta. He initially sought admission to the prestigious State Senior High School 1 but fell short of the entrance exam requirements and instead enrolled at State Senior High School 6, a newer public school in the city. Michael Bachelard wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald: “On his reading list were his father's books about Indonesia's first president, Sukarno. It is "quite normal", says Thayrun, for even poor villagers to own books by or about Sukarno, the speechmaker who inspired his country to break free of the Dutch after World War II, then led it for 20 years. "These books are mostly about [Sukarno's economic doctrine] Marhaenism ... Ordinary people read them and believe in Sukarno's teachings, and Jokowi's father was one of them."[Source: Michael Bachelard, Sydney Morning Herald, June 14 2014]

“Marhaen was an idealised poor farmer, and the economic policy named after him differs from Marxism because he was not a member of the employed proletariat. Indonesia's poor were, and remain, microbusiness owners working in the informal sector (without minimum wages, conditions or the need to pay tax). “Like Joko's father, they may own some income-producing goods such as a fishing net, a rubbish cart or a street stall, but still struggle to feed their families. Sixty-eight percent of employment in Indonesia remains in the informal sector.

“As a boy, Jokowi was determined to escape this fate using the most reliable method he knew — education. Come time for senior high school, he was desperate to get to SMA 1, the best school in Solo. But he found then, as now, it was the cheats who prospered. "I passed junior high with good marks ... but there were some people who cheated [and they got in before me]," he said recently. He was relegated to SMA 6, a technical school he felt was second best. "For almost six months I was so sad I locked myself in my room. I had no desire to go to school.” "He got sick because of that," says his mother, Sujiatmi. "He got fever and typhus." By 1980, Jokowi had overcome his disappointment and graduated dux, winning a place in the Forestry faculty at the respected Gadjah Mada University in neighbouring Yogyakarta. In 1985, he was awarded his forestry degree.

Joko Widodo’s Business Career

After graduating from university, Jokowi joined PT Kertas Kraft Aceh (KKA), a state-owned company in Aceh, where he worked from 1986 to 1988 as a supervisor overseeing forestry and raw materials at a pine plantation in what is now Bener Meriah Regency. Finding the work unfulfilling, he returned to Surakarta and spent a year in his grandfather’s furniture factory before establishing his own furniture business, Rakabu, named after his first child. [Source: Wikipedia]

The company was launched with an initial capital of Rp 15 million from his father and a bank loan. Specializing in teak furniture, Rakabu nearly collapsed at one point but survived after receiving a Rp 500 million loan from Perusahaan Gas Negara. By 1991, the company had begun exporting its products and achieved success in international markets, particularly in Europe. It was a French client named Bernard who popularized the nickname “Jokowi.”

Another Solo furniture maker, David Wijaya, recalls Jokowi as "a simple man, easygoing and approachable, yet very active and hardworking." Jokowi was also hands-on, driving timber around in his own car and moving among his workers in jeans and a white shirt. Jokowi would also make unannounced visits, known as blusukan in Javanese, to his factories to check if his employees were slacking off or cheating, says Wijaya. [Source: Michael Bachelard, Sydney Morning Herald, June 14 2014]

Jokowi's business thrived, and he became an exporter, opening showrooms in Europe, the U.S., and Asia. In 2002, Jokowi was elected chairman of the local Furniture Manufacturers' Association. As chairman of of this association he traveled abroad. Exposure to well-planned European cities during his business travels helped inspire his decision to enter politics and pursue urban reform in his hometown. After becoming mayor of Surakarta, he also entered a joint business venture with politician and former lieutenant general Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, co-founding PT Rakabu Sejahtera.

In 2018, Jokowi declared a net worth of approximately US$3.5 million, largely consisting of property holdings in Central Java and Jakarta.

Joko Widodo’s Family

Widodo married married his sweetheart, Iriana, in 1986. She was a friend of his sister's, and went off to his first job in a pulp mill in the remote highlands of Aceh's Takengon in Indonesia's far west. After four years, he returned to Solo with the pregnant Iriana to work for his uncle, who owned a furniture factory. Joko and Iriana have three children—two sons and a daughter. Their eldest son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka (born 1987), studied abroad in Sydney and Singapore, including at the Management Development Institute of Singapore (MDIS), and later served as mayor of Surakarta, Jokowi’s hometown, from 2021 to 2024. Their daughter, Kahiyang Ayu (born 1992), earned an undergraduate degree in food technology from the state-owned Sebelas Maret University in Surakarta. Their youngest son, Kaesang Pangarep (born 1994), completed his high school education at ACS International in Singapore and is best known as an online vlogger. Jokowi has five grandchildren: a grandson and a granddaughter from Gibran (born in 2016 and 2019), and two grandsons and a granddaughter from Kahiyang (born in 2018, 2020, and 2022). [Source: Wikipedia; Michael Bachelard, Sydney Morning Herald, June 14 2014]

According to AFP: The family is not poor — Mr Joko was a successful businessman — and one area where they have splashed out is the children’s education. The two sons attended high school in Singapore while the eldest did business courses in the city-state and Australia. Even in wealthy Singapore, the youngest son said, his parents did not spoil him. “I very rarely take the MRT (subway) because it is more ―expensive than a bus ride,” he wrote on his blog during his time in there, adding that his mother had refused to increase his ―meagre allowance. [Source: AFP, November 5, 2014]

Several members of Jokowi’s family later entered politics, particularly during the 2020 local elections. Gibran ran for mayor of Surakarta, while Jokowi’s son-in-law Bobby Nasution contested the mayoralty of Medan and his brother-in-law Wahyu Purwanto ran in Gunung Kidul Regency. Gibran and Bobby won their respective elections and took office in 2021, while Wahyu withdrew his candidacy at Jokowi’s request. In May 2022, Jokowi’s younger sister, Idayati, married Anwar Usman, the Chief Justice of Indonesia’s Constitutional Court. In September 2023, Kaesang joined the Indonesian Solidarity Party and was named its chairman shortly thereafter. The following month, Gibran was announced as a vice-presidential candidate in the 2024 presidential election.

According to Associated Press: Asked by journalists what he was going to do when he stepped down as president, Widodo said he planned to return to his family in his hometown, where he hoped play an active role in protecting the environment. “That's the plan,” Widodo told Bloomberg Television in a recent interview. “But sometimes, plans can change.” a.[Source: Niniek Karmini, Associated Press, February 11, 2024]

Joko Widodo Family When He Was President

A few months after Joko Widodo became President of Indonesia AFP reported: “With a wife who eschews designer outfits and daughter who is happy to queue at public health clinics, Joko Widodo’s family is setting a modest example in a region where leaders’ relatives are better known for greed and corruption. “Even now that Jokowi has been elected President, they still want to live like other ordinary people,” said Anggit Noegroho, who helped Mr Joko in numerous political campaigns and has known the family for a decade. [Source: AFP, November 5, 2014]

“When it comes to Mr Joko’s family, his wife, Iriana, 51, has forgone the designer clothes and fancy handbags, opting for plain shirts and trousers. His eldest son has set up a catering business in the family’s hometown of Solo, on Java, and drives a Mazda hatchback. When Mr Joko’s daughter, Kahiyang Ayu, 23, injured her hand, she insisted on being taken to a community health centre ―instead of an expensive private clinic, and waited for a doctor.

“A blog by Mr Joko’s youngest son, 17-year-old Kaesang Pangarep, has shone a light on the first family’s private life, with tales of his father playing practical jokes and worries about what to wear to school adding to the sense they are merely normal, middle-class folk. Still, it is still early days for the family and there are already signs that everything might not run smoothly. The eldest son faced criticism recently for responding angrily to reporters’ questions about why he did not appear with his father during the presidential campaign. “This man is too sensitive. He is not like his father,” one Twitter user commented.

Joko Widodo’s Character, Interests and Heavy Metal

Jokowi has often been described as a Muslim with a broadly secular outlook. His 2019 statement that religion and politics should be separated sparked public debate over whether he was advocating secularism. In June 2013, a film titled Jokowi, depicting his childhood and youth, was released. Jokowi expressed reservations about the film, saying he felt his life had been too ordinary to warrant a cinematic portrayal.

Jokowi is well known for his fondness for heavy metal music. According to The Economist, Jokowi owned a bass guitar signed by Metallica bassist Robert Trujillo, which was confiscated by Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK). During a state visit in November 2017, Danish Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen presented Jokowi with a signed Master of Puppets vinyl box set. To comply with transparency rules, Jokowi paid approximately IDR 11 million (about US$800) from his personal funds to claim the record after it was declared a state asset. Jokowi has publicly expressed admiration for bands such as Metallica and Megadeth, as well as Lamb of God, Carcass, and Napalm Death. He once traveled to Singapore for a Judas Priest concert. In 2018, Megadeth’s lead singer Dave Mustaine invited Jokowi to attend the band’s concert in Indonesia; although he could not attend, Jokowi opened the event via a video greeting. Earlier, in November 2013, while serving as governor of Jakarta, he was seen attending the Rock in Solo festival dressed casually.

Jokowi has frequently been noted for his physical resemblance to former U.S. president Barack Obama, and his outsider political background has also drawn comparisons to Obama’s rise. In addition, Jokowi is a practitioner of silat. He began training in the Setia Hati Terate style during junior high school and continued to refine his skills over the years. On 16 November 2013, he attained the rank of first-degree pendekar warga in the Persaudaraan Setia Hati Terate school.

Joko Widodo As Mayor of Surakarta (Solo)

n 2005, a group of business leaders in Solo sought a mayoral candidate who could cut through Indonesia’s entrenched bureaucracy and petty corruption. Rejecting “politics as usual,” they conducted a “fit and proper” test and chose Joko Widodo, a local furniture businessman committed to simplifying government procedures and attracting investment. Running with F. X. Hadi Rudyatmo after joining the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), Jokowi won the mayoral race with 36 percent of the vote—the largest share—and began a rapid political ascent. [Source: Michael Bachelard, Sydney Morning Herald, June 14 2014; Wikipedia]

As mayor of Surakarta from 2005 to 2012, Jokowi gained national attention for his hands-on, populist leadership style. He practiced blusukan—impromptu neighborhood visits—to monitor officials and hear residents’ concerns directly. His administration renovated traditional markets, expanded pedestrian areas, revitalized parks, strengthened environmental rules, and promoted the city as a center of Javanese culture and tourism under the banner “The Spirit of Java.” He also introduced local health and education insurance schemes, launched the Batik Solo Trans bus system, created Solo Techno Park, and repositioned Solo as a hub for conventions and cultural events.

Jokowi’s anti-corruption stance and practical approach won strong public support. He barred family members from bidding on city projects, kept a modest lifestyle, and famously donated his mayoral salary back to the city. His most celebrated achievement was the peaceful relocation of hundreds of street vendors from Banjarsari Park—long a source of conflict—after months of dialogue and the provision of low-interest loans. The move succeeded where previous administrations had failed, and businesses soon prospered in the new market.

Joko Widodo as Governor of Jakarta

Re-elected in 2010 as mayor of Surakarta with more than 90 percent of the vote, Jokowi announced he would not campaign but simply continue working. His popularity drew national attention, and in 2012 PDI-P leader Megawati Sukarnoputri, along with political ally Prabowo Subianto, urged him to run for governor of Jakarta. Despite the vast challenges of governing the capital, Jokowi accepted, departing Solo amid strong public goodwill—and even grassroots fundraising—from the traders and residents whose lives his mayoralty had transformed. The Jakarta campaign was smart, fresh and aimed at Indonesia's teeming, social media-adapted young. A viral musical video depicted the all-day ordeal that a young man undergoes to try to renew his ID card.In September 2012, Jokowi won a come-from-behind victory against incumbent Fauzi Bowo in a runoff, and leapt to national prominence. [Source: Michael Bachelard, Sydney Morning Herald, June 14 2014; Wikipedia]

As governor, he worked closely with a team drawn from his Surakarta years and with his deputy, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok). He continued his signature blusukan style, making frequent informal visits to neighborhoods and slums, which won broad public approval. Under his administration, Jakarta’s provincial budget and tax revenues rose sharply, accompanied by major transparency initiatives such as e-budgeting, online tax systems, and the public posting of meetings and activities. Jokowi introduced landmark social programs, including the Healthy Jakarta Card (KJS) for universal healthcare and the Smart Jakarta Card (KJP) to support students from low-income families.

His governorship also featured bureaucratic reforms through merit-based recruitment, efforts to regulate street vendors, large-scale flood control projects, and the long-delayed launch of the Jakarta MRT and LRT systems. While widely praised, his tenure was not without controversy, including criticism over healthcare implementation, evictions linked to flood mitigation projects, and isolated allegations of maladministration, which he defended as necessary steps for long-term urban improvement.

Joko Widodo Becomes a National Figure as Governor of Jakarta

Michael Bachelard wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald: With the eyes of the nation on him, one of his first acts was to turn up at 8am — the opening time — to a city district office in the suburb of Guntur where ID cards are processed. No official was in sight, so he sat down and waited, answering journalists' questions about indolent officials. Blusukan culture had arrived in Jakarta and the city lapped it up. [Source: Michael Bachelard, Sydney Morning Herald, June 14 2014]

“The social-media election campaign translated into a cult-like online following in a place where more people use Twitter and Facebook than almost anywhere else on the planet. Supporters howled down detractors as the new governor and his tough-talking deputy, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, introduced a free healthcare card and education funds for the poor, began building a much-delayed public transport system and shifted 14,000 squatters out of flood catchments and into low-cost apartments.

“Jokowi spent more time out of the office inspecting public works, handing out notebooks to children and taking indolent officials to task than he spent in it. He also sacked top city officials. "I will remind them, replace them ... remind them again. I will fire them; I will remind the others again and I'll fire them too if necessary," he said. "Check again, check again, check again. It's the only way."

“Deputy Basuki — virtually unique in Indonesian politics as a descendent of Chinese immigrants and a Christian — posted YouTube videos of himself dressing down public servants in budget meetings. He is often portrayed as the "bad cop" in the relationship, but he tells Good Weekend that Jokowi encouraged these outbursts and was "even stronger than me" in meetings.

“Indonesia is a sprawling country but 80 percent of its media is based in Jakarta, and the new governor's fame spread fast. In the remote village of Batukatak in North Sumatra, more than 1000 kilometers from the capital, local elder Ngalemi Sinuraya told this reporter in mid-2013: "Jokowi is for the orang kecil [the unimportant people] ... he is like us."

“Speculation about a presidential run began almost immediately. On the national stage, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono's ability to make a decision had ended well before his presidential term as, in the words of ANU academic Marcus Mietzner, he "withdrew into the joys of ceremony and increasingly pompous speeches".

Joko Widodo’s Bottom’s Up Approach

In 2012, just after Widodo became governor Jakarta, Pankaj Mishra wrote in Bloomberg: “He looks like Barack Obama: lean and coolly self-possessed in a way that seems as much Bogartian as Javanese. Emerging out of nowhere, and serenely vaulting over the heads of establishment politicians, he embodies the possibility of change. But here the resemblance to the U.S. president ends. Widodo has enjoyed hugely successful terms in office as the mayor of the Central Javanese city of Solo. Fulfilling most of his promises, he was re-elected with a voting percentage — 90 percent — more often enjoyed by dictators in the Central Asian “stans.”[Source: Pankaj Mishra. Bloomberg, November 4, 2012]

He said he had preferred to work from “bottom-up” rather than “top-down.” In a city of small merchants and traders, he had made it easier to procure business permits and licenses. He had supported local businessmen and traditional crafts and industries such as batik. In a country notorious for corruption and crony capitalism, he had favored small-food-cart owners over global convenience store chains and shopping malls.

Jokowi has quietly focused on developing a “people-centered economy.” This involves helping to upgrade traditional crafts and skills so that local products can compete with imports from China, while also deepening regional identities (a distinctive feature of central Javanese culture). As for his job as governor, according to Jokowi, Jakarta needs not more roads and freeways — the hundreds of new car owners every day would quickly turn those into parking lots as well — but more public mass transport. A monorail project, long dormant, may now be revived.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, , Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025