ELECTION IN INDONESIA IN 2014

2014 Indonesia Presidential Election Result

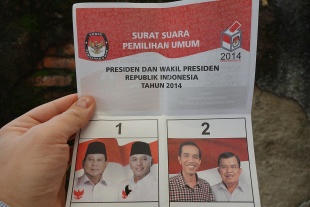

Candidate — Joko Widodo — Prabowo Subianto

Party — PDI-P — Gerindra

Alliance — Great Indonesia — Red-White

Running mate — Jusuf Kalla — Hatta Rajasa

Popular vote — 70,997,833 — 62,576,444

Percentage — 53.15 percent — 46.85 percent

Registered voters— 193,944,150 (Increase 9.97 percent)

Turnout — 69.58 percent (Decrease 2.99pp) [Source: Wikipedia]

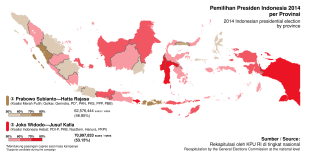

Indonesia held presidential elections in July 2014, pitting former general Prabowo Subianto against Joko Widodo, the popular governor of Jakarta known by his nickname Jokowi. Incumbent president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was constitutionally barred from seeking a third term. Widodo ended up winning a very close election. July 22, the General Elections Commission (KPU) declared Widodo the winner, and he and his running mate, Jusuf Kalla, were sworn in for a five-year term on October 20, 2014. Widodo’s victory underscored the growing appeal of reformist leadership in Indonesia, even as the country continued to face persistent challenges from corruption and periodic attacks by Islamic extremist groups. [Source: Wikipedia, Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Legislative elections were held in April 2014. Under Indonesia’s 2008 election law, only political parties or coalitions holding at least 20 percent of seats in the House of Representatives (DPR), or having won 25 percent of the popular vote in the parliamentary elections, were eligible to nominate presidential candidates. Although the rule was challenged in the Constitutional Court, it was upheld in January 2014. Because no single party met the threshold in the April 2014 legislative elections, competing coalitions were formed ahead of the presidential contest.

In 2014 there were 480,000 polling stations, 190 million eligible voters. A total of 2,659 commissioners at national and sub-national level were appointed. The fixed voter list for the 2014 election established in November 2013 recorded 186.61 million registered voters.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JOKO WIDODO: HIS LIFE. CAREER, FAMILY, INTERESTS AND RISE TO POWER factsanddetails.com

JOKO WIDODO AS PRESIDENT: HIS FOLKSY STYLE, ACHIEVEMENTS AND CRITICS factsanddetails.com

2024 ELECTIONS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

REFORMASI AND THE POST–SUHARTO ERA factsanddetails.com

MEGAWATI SUKARNOPURTI (PRESIDENT OF INDONESIA 2001-2004): LIFE, POLITICAL CAREER, FAILURES factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO: HIS LIFE, PERSONALITY AND RISE TO POWER factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER SUHARTO: NEW ORDER, DEVELOPMENT, FOREIGN POLICY factsanddetails.com

REPRESSION UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: KILLERS, VICTIMS, REASONS factsanddetails.com

CORRUPTION AND FAMILY WEALTH UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998: PRESSURES, EVENTS, RESIGNATION factsanddetails.com

INDONESIAN ELECTIONS IN 2004 AND 2009 factsanddetails.com

SUSILO BAMBANG YUDHOYONO (PRESIDENT OF INDONESIA 2004-2014): LIFE, CAREER, INTERESTS factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER YUDHOYONO (2004-2014) factsanddetails.com

Early Optimism for Joko Widodo in Indonesia’s 2014 Presidential Election

The outlook for the 2014 presidential election shifted shifted dramatically when the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) nominated the widely popular Jakarta governor, Joko Widodo, as its candidate. His nomination significantly boosted the party’s prospects. Opinion polls at the time showed the presidency was Widodo’s to lose, with more traditional figures such as former general Prabowo Subianto and tycoon Aburizal Bakrie trailing well behind. The enthusiasm surrounding Widodo was reflected in a sharp rise in market confidence, with Jakarta share prices jumping more than 3 percent following the announcement. [Source: Jonathan Thatcher, Reuters, March 15, 2014]

Analysts attributed the optimism to expectations that Jokowi would bring decisive and clean leadership. As one market strategist observed, investors believed Indonesia might finally gain a president willing to take difficult decisions, with a strong reputation for integrity and the promise of a smooth transfer of power. Widodo was seen as a break from the era of dictator Suharto. He won praise for his common touch and for being a clean leader in a country plagued by corruption. In contrast, Prabowo was a top military figure during the Suharto era who admitted to ordering the abduction of democracy activists. However, he has won over many voters by pledging to be a strong leader. At the end of the campaign Widodo was fighting to hold on to his slim lead in the polls, down from a substantial margin several before months. On the eve of the election pollsters said the race was now too close to call.

The electorate in Indonesia has gotten younger and younger. Nearly 30 percent of eligible voters, around 54 million people, were under the age of 30, and almost half were first-time voters. Many were drawn to Jokowi’s plainspoken, service-oriented image, which resonated not only with young Indonesians but also with the growing middle class and the poor, among whom roughly 40 percent of the population still lived in or near extreme poverty.

A former furniture manufacturer, Jokowi had in little more than a year as Jakarta governor transformed his unpretentious “I am here to serve you” approach into a powerful political brand, offering a sharp contrast to Indonesia’s long-dominant authoritarian elites. Yet those old forces remained influential. Both PDI-P and the pro-business Golkar Party, expected to dominate the parliamentary elections, continued to draw heavily on the legacies of their autocratic founders.

PDI-P remained closely associated with Megawati Sukarnoputri, daughter of Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno, whose image and nationalist legacy featured prominently in party symbolism. Golkar, meanwhile, increasingly invoked the early economic successes of Suharto, who ruled Indonesia for more than three decades before being ousted in 1998 amid mass protests and economic collapse. In May, Indonesia's most popular Islamic party — “The National Awakening Party (PKB) — announced it would support Widodo’s bid for the presidency. The PKB became the third party in Jokowi’s growing coalition. It is aligned with Indonesia's largest Muslim organisation. The addition of the PKB to Widodo’s coalition, which also included the National Democrat (NasDem) party, was expected to help give Jokowi a broad base of support to help him pass major reforms if elected. [Source: Kanupriya Kapoor, Reuters, May 10, 2014]

Rough Start of Joko Widodo’s 2014 Campaign

Michael Bachelard wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald: “Before Jokowi, the field of potential replacements was a mix of failed former candidates and Suharto-era relics — thrice-beaten Megawati, disliked businessman Aburizal Bakrie and Prabowo, an ex-general with a poor human-rights reputation. In this company, Jokowi seemed inspired, but for 19 months he refused be drawn. Jakarta, meanwhile, was proving tougher than Solo. The 2014 floods were as bad as any year, the healthcard had teething problems and Jokowi's attempt to replicate his success with street traders largely failed. More than 500 smallholders at the Tanah Abang market he'd encouraged to move off the streets and into a three-level market building had, less than a year later, gone back, complaining that customers would not climb the three storeys to their stalls. Local gangsters were also offering inducements for stallholders to return to the streets. [Source: Michael Bachelard, Sydney Morning Herald, June 14 2014]

On the day Good Weekend visited, city security officials were doing nothing about the flourishing illegal street trade, to the chagrin of the legal businesspeople watching from above.

"They should enforce the law but look at them. What's the conspiracy?" asks Joni, a stallholder who hasn't had a customer for weeks.

"We don't sell Jokowi T-shirts. We're against that," states clothing stallholder Yasnita.

"If Jokowi can't even manage Tanah Abang, how can he manage the country?" adds Joni.

“As the campaign for president increased in intensity, these negatives were being amplified nationally: Jokowi is abandoning Jakarta after only 18 months, the job is not half done; he's just the velvet glove on the real iron fist, [deputy] Basuki; he's too inexperienced; running a country is too big a job for blusukan and micromanagement. In a country desperate for infrastructure projects to be delivered without corruption, an instinct for hands-on problem-solving would be welcome but, as Yon Thayrun points out, "He can't check everything: Jokowi only has two hands and 10 fingers."

Election Rallies in Indonesia’s 2014 Election

As campaigning for the 2014 presidential election was drawing to a close, AFP reported: “Presidential hopeful Joko Widodo pledged to build a "new history" for Indonesia at a huge campaign rally, a last push to win votes in a tight election race. Tens of thousands of cheering supporters waved flags emblazoned with pictures of Widodo, at Jakarta's main stadium on the final day of campaigning. Backers of his only rival, Prabowo Subianto, were holding rallies to show their support across the country, although the ex-general took time out to prepare for a TV debate in the evening. At the rally, Widodo — seen as a fresh face in a country still dominated by figures from the autocratic Suharto era — told the cheering crowd: "We are on the verge of building a new history." [Source: AFP, July 6, 2014 ^|^]

“The Jakarta governor added that his push for the presidency had been "hit by smear campaigns but we didn't fall apart because we truly believe in the Republic of Indonesia". He was referring to a flood of negative attacks on him that have eroded his popularity, including that he is not a Muslim, a damaging charge in the world's most populous Muslim-majority country. As well as the smear campaigns, Prabowo has extended his lead due to a slick, well-funded campaign, a contrast with Widodo's often disorganised effort. Before Widodo's speech, dozens of singers and bands performed for free to show their support.” After this “no more campaigning is allowed before the vote.

Before “the candidates and their running mates clashed in the last of five televised debates, which focused on food, energy and the environment. Widodo and his running mate, former vice-president Jusuf Kalla, appeared more energetic and commentators said they outclassed Prabowo and his deputy, Hatta Rajasa, with several well-judged attacks. In their closing statements, Widodo pledged to "bring change, breakthrough" to Indonesia, while Prabowo vowed to "prioritise welfare and sovereignty". "Jokowi and Kalla looked better," said Tobias Basuki, an analyst from Jakarta-based think-tank the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, adding the other pair "seemed to have lost their composure". ^|^

Rock Stars, Numbers and the 2014 Presidential Campaign

The Wall Street Journal reported: Rock stars in Indonesia are lining up behind presidential candidate Widodo and his running mate Jusuf Kalla with less than a month before July 2014 election. The pair have garnered support from dozens of musicians, many of whom gathered to host a get out the vote concert. At the event, a newly released song written by several all-star musicians, including members of Slank and pop singer Ello, played on repeat, reminding supporters to vote for Jokowi, as Mr. Widodo is popularly known. “Two-finger salute, don’t forget to vote for Jokowi,” rang the chorus, a reference to the team’s placement on July’s election ballot. [Source: Anita Rachman and Sara Schonhardt, Wall Street Journal, June 12, 2014]

“Challengers Prabowo Subianto and Hatta Rajasa drew the top spot earlier this month, when the teams selected their numbers on the ticket. Since then, Mr. Widodo’s campaign team has embraced the number two as one of its hallmarks, adopting the “two-finger salute,” an imitation of the peace sign once flashed by 1960s anti-war activists. “The song gives me shivers,” said Nur Hidayat, a 25-year-old supporter, who had come from East Jakarta to meet others in the Jokowi camp.

“Mr. Hidayat was one of a few thousand people, many of them under 30, gathered at the stadium complex where the event was being held to show their support for 52-year-old Mr. Widodo. Hosted by dozens of musicians and youth organizations calling themselves the Harmonious Revolution, the event highlighted a piece of Mr. Widodo’s platform that calls for a new way of thinking about leadership and governance, something he has dubbed his “Mental Revolution.” But it was metal that was the real highlight of the afternoon, with rock band Slank appearing as its headliner. Other artists on the roster included Kill the DJ, a popular rap group from Central Java, famous pop singer Krisdayanti and two of the stars of Jalanan, a musical documentary that follows the lives of three buskers in Jakarta.

Mr. Subianto also has his share of musical supporters, including rock musician Ahmad Dhani and crooner Rhoma Irama, the self-proclaimed King of a popular Indonesian music genre known as dangdut. Nurul Arifin, a campaign spokeswoman for Mr. Subianto, said the team has no plans to host its own concert for now — though it’s getting out its message in other ways. Mr. Subianto’s Great Indonesia Movement Party (Gerindra) has formed a youth wing to win over the 30 percent of the voting population under 30, and has a savvy social-media campaign that includes a dedicated YouTube channel and a mascot who fights for justice called Mas Garuda, a mythological bird that is also the national symbol.

Indonesia’s Presidential Debates in 2014

On the presidential debated in 2014, Yohanes Sulaiman wrote in The Conversation: “In the lead-up to the election, Indonesia’s General Elections Commission (KPU) scheduled five debates. With only two candidates running for the presidency, this year’s debates are more divisive than the 2009 debates between Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY), Megawati Sukarnoputri and Jusuf Kalla. We see more die-hard supporters in the audience, chanting slogans for their candidates as if they were barracking for a team in a sporting event. But the audience’s ample enthusiasm is not a reflection of the quality of debate. Like the past three debates, this one had the same problems: none of the candidates was willing to bear bad news to the people; neither actually discussed real problems. [Source: Yohanes Sulaiman, Indonesian Defense University, The Conversation, June 30, 2014]

“For instance, during one debate on the issue of human resource development and research and technology, Hatta, the chairman of the National Mandate Party (PAN) attacked Jokowi-Kalla’s opposition to the national exam. Kalla, who once served as SBY’s vice-president, responded by stressing they would evaluate the national exam, not abolish it. None of them, however, discussed the real mess behind the issue, notably the high number of students passing the exam. This may sound counter-intuitive, but considering the poor quality of Indonesian teachers in remote regions, which both candidates acknowledged, it is simply mind-boggling that 99 percent of high school students in Indonesia passed the exam.

“Similarly, when the moderator asked their solution to stop the “brain drain” from Indonesia, both candidates proposed better compensation to keep skilled workers from leaving the country. They ignored the fact that many of these people were leaving out of frustration at having to deal with red tape and being unable to work in an environment where corruption, collusion and nepotism are rampant. In general, both vice-presidential candidates were saying the same things, albeit in different ways. They agreed that the government needed to give more funding to education and technological research, as well as provide incentives for private sector research. They agreed that the brain drain should be stopped. They also agreed that the government needed to attract talents back to the country and pay them attractive compensation so they would stay.

“So who won the debate? Honestly, it was so boring that it was difficult to pay attention to the arguments. While Kalla was a favourite due to his aggressive style, this time Hatta won — though barely — on the point of substance. If we were keeping scores, the fourth debate would bring the rivals to a draw. Jakarta governor Jokowi owned the first debate, as he managed to shed doubts about his leadership capability. At the same time, Kalla managed to put Prabowo, the former special forces unit commander, on the defensive with his questions on the issue of human rights.

“Jokowi also overall won the third debate on foreign policy and national security. He brought up the issue of Australia-Indonesia relations in the debate. Jokowi looked in control despite a lack of substance from both candidates in their answers. Jokowi even managed to insert a jab at his detractors, that he could be decisive if needed. Prabowo performed better in the second presidential debate. Discussing economic development and social welfare, he attacked Jokowi’s programs right from the start. Jokowi looked unprepared for the aggressive questionings in the second debate. Even though he managed to stage a comeback, the overall impression of the debate was that Prabowo won the match and Jokowi was unable to maintain his momentum.

“The fifth debate, which will again be between the two presidential candidates and their running mates, hopefully will be far more interesting than Sunday’s debate. With Jokowi and Kalla again able to run as a pair, they should be a formidable team. Prabowo and Hatta might need to press ahead aggressively if they want to catch Jokowi-Kalla flat-footed.

“Despite all the excitement about the debates, they have done little to highlight the issues at stake or show the differences between the candidates. Rather, the debates merely serve to energise the candidates’ bases, giving them soundbites to use to show how good their candidates are in public speaking.

Smear Campaigns in the 2014 Indonesian Presidential Race

A smear campaign against Widodo was launched that included allegations linking him to communism, questioning his religion and ethnicity, and distributing a defamatory tabloid in Islamic boarding schools. Prabowo characterized Widodo as an unsophisticated, small-town politician who lacked the ability to lead a large nation. In response, Widodo said Prabowo would be the only president in Indonesian history to take office with prior experience in running a government. “It’s about management,” Jokowi said. “How to plan, how to organize, how to decide actions. In my opinion, the most important thing in governance is management control.” [Source: Joe Cochrane, New York Times, July 22, 2014]

Michael Bachelard wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald: A "black campaign" of libels, including a fake obituary using Jokowi's supposed "real" Chinese name, Oey Hong Liong, is circulating online, but most damaging is the suggestion that Jokowi is merely a puppet controlled by PDI-P chairwoman Megawati. She is deeply unpopular outside her fan club, but still calls the shots in her party. "I don't mind being called a puppet," Jokowi declared in April."But I'm the puppet of the people." [Source: Michael Bachelard, Sydney Morning Herald, June 14 2014]

“The impression, though, is strong and regularly reinforced by the Sukarno family itself, which is struggling to cede power. Jokowi had to endure a long and humiliating wait before Megawati decided in March to forego another presidential run and choose him. Her even less popular daughter, Puan Maharani — who is running the PDI-P campaign — makes little pretence of liking the newcomer. "People had hoped that power could be retaken by the descendants of Sukarno," Puan said in a recent interview with Tempo magazine, adding: "Anyone who betrays [Sukarno's] convictions ... does not need to be strangled or beaten up. He just disappears, believe it or not."

Jokowi said these “black campaigns” significantly damaged his electability and criticized authorities for failing to stop them, though he remained publicly optimistic about voter enthusiasm. Police opened a libel investigation into the tabloid, whose editor had links to the president’s office, as the ruling Democratic Party moved to support Prabowo shortly before the vote .Polls showed Jokowi holding only a narrow lead—around 52 percent to 48 percent—with a large share of voters still undecided and warnings from analysts about the risk of fraud or post-election unrest. President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono ordered security forces to safeguard the election and transition process.

Indonesian Presidential Race Tightens

Less than a week before Indonesia’s presidential election, the race tightened sharply as front-runner Joko Widodo (“Jokowi”) lost most of his earlier commanding lead, with polls showing former general Prabowo Subianto closing the gap. Analysts attributed the shift partly to millions of undecided voters moving toward Prabowo and to widespread smear campaigns against Jokowi, smear campaigns against Jokowi. [Source: Associated Press, July 4, 2014]

Michael Bachelard wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald: “A disappointing performance by PDI-P in the parliamentary elections in April further fuelled the negatives. The party expected that the so-called "Jokowi effect" would win at least 27 percent of the vote — it came away with just 18.95 percent, still the winner in the 12-party race, but well below expectations. Suddenly Jokowi, the giant killer in Jakarta, the man who did not even need to campaign in Solo, looked vulnerable. Indonesia's sharemarket and currency both fell. [Source: Michael Bachelard, Sydney Morning Herald, June 14 2014]

“In the weeks following the parliamentary poll, PDI-P made it worse, seemingly mired in indecision over coalition negotiations and the choice of a running mate. The latter was eventually resolved (at some risk to Jokowi's cleanskin image) by appointing Megawati's favourite political war-horse, former vice-president Jusuf Kalla.

“Meanwhile, as rival Prabowo energetically spelled out a populist platform and projected toughness and decisiveness, Jokowi's Javanese habit of speaking little, and then only in hints and riddles, failed to establish a presidential program or persona. The result was a dip in the polls from 52 percent to 47 percent going into May. Prabowo's numbers rose almost 10 percent, from 23 percent to 32 percent. PDI-P has reliably snatched defeat from the jaws of victory in the post-Suharto era, and the parliamentary result raises serious questions about the party's ability to run a campaign.

Prabowo Subianto experienced a surge in popularity as the election neared after receiving endorsements from the country's largest political parties and running an efficient ground campaign. Analysts said his campaign was more effective and better financed. He also enjoyed the support of two of the country’s largest television stations. The campaign period was marred by smear tactics, known locally as black campaigns, from both camps. Widodo blamed his decline in the polls, from a lead of over 12 percentage points in May to just 3.5 points before the election, on character attacks that accused him of not being a devout Muslim, among other things. He has denounced the charges as lies. ‘I think these black campaigns were effective enough to convince communities,’ said Hamdi Muluk, a political analyst from the University of Indonesia. "And that has directly ruined Widodo’s image." [Source: Niniek Karmini, Associated Press, July 23, 2014]

Prabowo's Withdrawal and Turmoil After the 2014 Presidential Elections

After all the voting was done, both candidates in Indonesia’s 2014 presidential election claimed victory. Reputable quick-count surveys showed Jakarta governor Joko Widodo (“Jokowi”) winning about 52 percent of the vote. Prabowo Subianto, rejected the quick counts, claimed his own data showed him ahead, and alleged massive fraud. Prabowo withdrew from the process before the official announcement and prepared a legal challenge to the results at the Constitutional Court, citing widespread irregularities. [Source: Niniek Karmini, Associated Press, July 23, 2014]

On July 22, 2014, as the General Elections Commission (KPU) prepared to announce the official results, Prabowo Subianto withdrew from the vote recapitulation process, alleging “structured and systematic” fraud and declaring the election unconstitutional. He signaled his intention to challenge the outcome, though there was confusion over whether he had formally withdrawn or simply rejected the count.

Observers rejected Prabowo’s claims, describing the election as generally free and fair and noting that his legal options were weak given the vote margin and the consequences of withdrawal under election law. The move briefly unsettled markets, with the rupiah and stock index falling. Despite the walkout by Prabowo’s camp, the KPU proceeded and declared Joko Widodo the winner with 53.15 percent of the vote to Prabowo’s 46.85 percent. The result marked the closest presidential election since Indonesia’s democratic transition in 1998. Still Widodo’s margin of victory was condidered significant and decisive.

Indonesia’s Constitutional Court unanimously upheld the results of the 2014 presidential election, rejecting all of Prabowo Subianto’s fraud claims and clearing the way for Joko Widodo’s inauguration in October. The ruling, which cannot be appealed, dismissed allegations that tens of millions of votes were invalid. The verdict came amid protests by Prabowo supporters in Jakarta, which briefly turned violent and were dispersed by police using tear gas. Despite the unrest, authorities later restored calm. [Source: George Roberts, abc.net, August 22, 2014]

2014 Indonesian Legislative Elections

In the parliamentary elections, Megawati Sukarnoputri’s Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) finished first with 109 seats, followed by Golkar with 91 and Prabowo’s Gerindra party with 73, among ten parties that entered parliament. Prabowo was backed by a coalition that collectively controlled more than 60 percent of DPR seats, including Golkar. Joko Widodo led a smaller parliamentary coalition but won the presidential election. . The ruling Democratic Party of outgoing president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono—constitutionally barred from a third term—saw its support collapse after graft cases ensnared senior figures, including a former party chairman and a cabinet minister. [Source: Jonathan Thatcher, Reuters, March 15, 2014]

Legislative elections were held in Indonesia on April 9, 2014 to elect 136 members of the Regional Representative Council (DPD), 560 members of the People's Representative Council (DPR) and members of regional assemblies at the provincial and regency/municipality level. There are more than 6,600 candidates vying for 560 seats in the House of Representatives and 132 in the Upper House. Another 16,000 hopefuls are competing at the provincial and district levels, making it arguably the world's largest single-day election process. A total of 20,389 seats were contested, most of them in the People's Regional Representative Council. [Source: Wikipedia, Australia News Network]

The Indonesian Democratic Party won the election with 18.95 percent of the vote, followed by the Golkar Party with 14.75 percent and the Great Indonesia Movement Party with 11.81 percent. However, none of the parties can submit their own presidential candidate for the 2014 Indonesian presidential election because they did not reach the 20 percent electoral threshold required for presidential candidates.

A total of 46 parties registered to take part in the election nationwide, from which only 12 parties (plus 3 Aceh parties) passed the requirements set by the General Elections Commission (KPU).

2014 Indonesian People's Representative Council election results Parties Votes percent Swing Seats percent +/-

Indonesian Democratic Party — Struggle (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan, PDI–P) 23,681,471 18.95 Increase4.92 109 19.46 Increase15

Party of the Functional Groups (Partai Golongan Karya, Golkar) 18,432,312 14.75 Increase0.30 91 16.25 Decrease15

Great Indonesia Movement Party (Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya, Gerindra) 14,760,371 11.81 Increase7.35 73 13.04 Increase47

Democratic Party (Partai Demokrat, PD) 12,728,913 10.19 Decrease10.66 61 10.89 Decrease87

National Mandate Party (Partai Amanat Nasional, PAN) 9,481,621 7.59 Increase1.58 49 8.75 Increase3

National Awakening Party (Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa, PKB) 11,298,957 9.04 Increase4.10 47 8.39 Increase19

Prosperous Justice Party (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera, PKS) 8,480,204 6.79 Decrease1.09 40 7.14 Decrease17

United Development Party (Partai Persatuan Pembangunan, PPP) 8,157,488 6.53 Increase1.21 39 6.96 Increase1

Nasdem Party (Partai Nasdem, Nasdem) 8,402,812 6.72 New 35 6.25 New

People's Conscience Party (Partai Hati Nurani Rakyat, Hanura) 6,579,498 5.26 Increase1.49 16 2.86 Decrease1

Crescent Star Party (Partai Bulan Bintang, PBB) 1,825,750 1.46 Decrease0.33 0 0.00 Steady

Indonesian Justice and Unity Party (Partai Keadilan dan Persatuan Indonesia, PKPI) 1,143,094 0.91 Increase0.01 0 0.00 Steady

Total 124,972,491 100.00 Steady 560 100.00 Steady

Spoilt and null votes 14,601,436 7.86 Decrease6.57

Voter turnout 139,573,927 75.11 Increase4.12

Electorate 185,826,024

Indonesia's Islamic political parties did better than expected in the 2014 elections — taking over . 30 percent of the total vote. Despite Indonesia’s overwhelmingly Muslim population, Islamic parties were not perform strongly in part because the standing of the previously prominent Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) had been damaged by a high-profile corruption scandal. As of 2014 there were five Muslim-based parties are running: the United Development Party (PPP), the National Awakening Party (PKB), the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), the Crescent Star Party (PBB) and the National Mandate Party (PAN). [Source: Kanupriya Kapoor and Randy Fabi, Reuters, April 9, 2014]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, , Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025