TIMELINE FOR ANCIENT INDONESIA

1.5 million to 100,000 Years Ago: Homo erectus (“Java Man”) roams Java. Fossils were discovered in East Java in 1891.

190,000 to 50,000 Years Ago; Homo floresiensis, small human-like hominids, and often called hobbits, reside on the island of Flores.

63,000 Years Ago: The first traces of Homo sapiens appeared in Indonesia as people were able to migrate back and forth from the Asian mainland. The islands of western Indonesia formed a peninsula with mainland Southeast Asia that some call Sundaland. Papua New Guinea and neighboring islands formed an extension of Australia.

17,000 Years Ago: The Ice Age began to subside, causing sea levels to gradually rise and cover landmasses, forming the islands of the Indonesian archipelago.

Between 5,000 and 3,000 B.C.: Austronesian migrations from southern China began moving through Indonesia.

A.D. 100: Trade routes open between China and India, creating great wealth in some regions and allowing foreign influences to flourish. Indians arrived in Sumatra, Java, and Bali.

Third Century: The southern Sumatra area near Jambi and western Java became major entrepots, linking the Java Sea region with China.

Fourth Century: The first known inscriptions in South Indian Pallava script were used in announcements by King Mulavarman in East Kalimantan.

Fifth century: According to Chinese chronicles, Indonesian ships controlled most of the archipelago's trade and sailed as far as China.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JAVA MAN AND HOMO ERECTUS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

HOMO FLORESIENSIS: HOBBITS OF INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com

EARLIEST PEOPLE OF INDONESIA: NEGRITOS, PROTO-MALAYS, MALAYS AND AUSTRONESIAN SPEAKERS factsanddetails.com

OLDEST CULTURES IN INDONESIA AND PEOPLE THERE BEGINNING 10,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

FIRST INDONESIAN KINGDOMS: HINDU-BUDDHIST INFLUENCES, SEAFARING, TRADE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

SRIVIJAYA KINGDOM: HISTORY, BUDDHISM, TRADE, ART factsanddetails.com

MAJAPAHIT KINGDOM: HISTORY, RULERS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF ISLAM IN INDONESIA: ARRIVAL, SPREAD, ACEH, MELAKA, DEMAK factsanddetails.com

SPICES, TRADE AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA WHEN EUROPEANS FIRST ARRIVED: SPICES, POWERFUL STATES, DEALS, ISLAM factsanddetails.com

EARLY INDIANS, CHINESE AND ARABS IN INDONESIA: IBN BATTUTA, YIJING, ZHENG HE factsanddetails.com

EARLY EUROPEAN EXPLORERS IN INDONESIA: MARCO POLO, NICOLÒ DEI CONTI, MAGELLAN'S CREW factsanddetails.com

AGE OF EUROPEAN EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY DUTCH PERIOD IN INDONESIA AND THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY (VOC) factsanddetails.com

DUTCH EMPIRE: WEALTH, EXPLORATION AND HOW IT WAS CREATED factsanddetails.com

DUTCH, THE SPICE TRADE AND THE WEALTH GENERATED FROM IT factsanddetails.com

factsanddetails.com

NETHERLANDS INDIES EMPIRE IN THE 19TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER DUTCH RULE IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

RISE OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

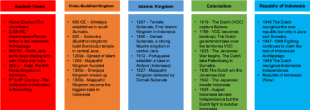

Period of Kingdoms in Indonesia

Eighth Century: Borobudur was built by the Sailendra dynasty, a powerful Javanese kingdom that ruled primarily in the ninth century (around 778–850 CE). The Indian Gupta dynasty had a strong influence on the region in the seventh and eighth centuries, introducing Buddhism. [Sources: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006; Matthew Easton, Worldmark Encyclopedia of National Economies, Gale Group Inc., 2002; World Encyclopedia, Oxford University Press 2005; Clark E. Cunningham, International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

Meanwhile, Srivijaya emerged in Sumatra as the first great power in the region. Inscriptions reveal the teaching of Tantric Mahayana Buddhism. Srivijaya controlled trade in the Malacca Strait by providing a safe port at Palembang. The Sailendra Dynasty developed a great rice-plane polity in Central Java. They ruled for 200 years and constructed the giant Buddhist monument Borobudur.

Tenth Century: Most Javanese rulers lost power for unclear reasons, perhaps due to wars with Srivijaya of Sumatra. Airlangga founded Java’s first great empire, uniting central and eastern Java and Bali.

Thirteenth Century: Hinduism replaced Buddhism as the main religion. Kertanegara began a period of rapid cultural development and expansion beyond Java. After his death, his son-in-law founded the most powerful kingdom ever to arise in Java: Majapahit.

1292: The Italian explorer Marco Polo wrote about the Islamic sultanate in Aceh, in northern Sumatra.

Fourteenth Century: Islam began to take hold in Indonesia. By the end of the sixteenth century, Islam had become the dominant religion.

Majapahit’s fleets sailed to the outer islands as part of an expansive plan by its prime minister, Gajah Mada. A chronicle from this period, the Nagarakertagama, claimed that the empire held sovereignty from Sumatra to Papua New Guinea. Srivijaya declined after losing control of maritime commerce to Chinese shipping.

1500: The fall of Majapahit marked the end of the last Hindu-Buddhist empire. Majapahit declined after losing control of the island shipping trade and facing opposition from the expanding Muslim kingdom of Demak.

Sixteenth Century: The Islamic Mataram kingdom rose to power, subjugating most of Java and invading the formerly Hindu–Buddhist interior.

Indonesia and Trade

Many parts of the archipelago played a role in local and wider trading networks from early times, and some were further connected to interregional routes reaching much farther corners of the globe. Nearly 4,000 years ago, cloves—which until the seventeenth century grew nowhere else in the world except five small islands in Maluku—had made their way to kitchens in present-day Syria. By about the same time, items such as shells, pottery, marble, and other stones; ingots of tin, copper, and gold; and quantities of many food goods were traded over a wide area in Southeast Asia. As early as the fourth century BC, materials from South Asia, the Mediterranean world, and China—ceramics, glass and stone beads, and coins— began to show up in the archipelago. In the already well-developed regional trade, bronze vessels and other objects, such as the spectacular kettledrums produced first in Dong Son (northern Vietnam), circulated in the island world, appearing after the second century B.C. from Sumatra to Bali and from Kalimantan and Sulawesi to the eastern part of Maluku. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Around 2,000 years ago, Javanese and Balinese were themselves producing elegant bronze ware, which was traded widely and has been found in Sumatra, Madura, and Maluku. In all of this trade, including that with the furthest destinations, peoples of the archipelago appear to have dominated, not only as producers and consumers or sellers and buyers, but as shipbuilders and owners, navigators, and crew. The principal dynamic originated in the archipelago. This is an important point, for historians have often mistakenly seen both the trade itself and the changes that stemmed from it in subsequent centuries as primarily the work of outsiders, leaving Indonesians with little historical agency, an error often repeated in assessing the origins and flow of change in more recent times as well. *

By the middle of the first millennium BC, the expansion of wet-rice agriculture and, apparently more importantly, certain requirements of trade such as the control of local commodities, suggested new social and political possibilities, which were seized by some communities. For reasons not well understood, most—and all of those that endured—were located in the western archipelago. Already acquainted with a wider world, these Indonesians were open to, and indeed actively sought out, new ideas of political legitimation, social control, and religious and artistic expression. *

Their principal sources lay not in China, with which ancient Indonesians were certainly acquainted, but in South Asia, in present-day India and Sri Lanka, whose outlooks appear to have more nearly reflected their own. This process of adoption and adaptation, which scholars have somewhat misleadingly referred to as a rather singular “Hinduization” or “Indianization,” is perhaps better understood as one of localization or “Indonesianization” of multiple South Asian traditions. It involved much local selection and accommodation (there were no Indian colonizations), and it undoubtedly began many centuries before its first fruits are clearly visible through the archaeological record. Early Indonesia did not become a mini-India. Artistic and religious borrowings were never exact replications, and many key Indic concepts, such as those of caste and the subordinate social position of women were not accepted. Selected ideas filled particular needs or appealed to particular sensibilities, yet at the same time they were anything but superficial; the remnants of their further elaboration are still very much in evidence today. *

Colonization of Indonesia

By the early sixteenth century, Portuguese ships had entered Indonesian waters in search of high-value spices—cloves, nutmeg, mace, and pepper. In Europe, nutmeg and cloves were prized to the point of superstition; people carried pomanders of these spices as protection against plague. This demand drew European powers to the Banda Islands in Maluku, sparking a fierce competition among Portugal, Spain, England, Denmark, and Holland for control of one of the world’s smallest but most coveted island groups. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

As Java and Sumatra were largely Islamic by the sixteenth century and Bali had a deeply rooted Hindu culture, Portuguese traders and missionaries found it easier to gain footholds in the animist regions of eastern Indonesia, including Flores, Timor, and Maluku. Their vessels—mostly war galleons—secured ports through superior weaponry, naval skill, and aggression. The Portuguese established Catholic missions in North Sulawesi, Ternate and Ambon, and in Flores and Timor, but in the early 1600s were largely displaced by the Dutch, remaining only in parts of Flores and Timor. Portuguese rule in Maluku was marked by violence and a crusading zeal reminiscent of medieval Europe. Focused more on plunder than trade, they alienated local populations to the point that popular hostility hastened their downfall.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) began trading in Indonesia in the seventeenth century, eventually ousting the Portuguese and evolving into a colonial power. One VOC governor, Jan Pieterszoon Coen, became notorious for his brutal regime. In 1621, he established a post in the Banda Islands to exploit nutmeg production, selling much of the population into slavery and creating torture chambers to silence opposition. He used Japanese mercenaries to kill local inhabitants and English competitors alike. Fearing English influence and disdaining the local population, Coen ordered many nutmeg trees uprooted for transfer elsewhere. The English later did the same, even removing tons of Banda’s unique soil to transplant the spice to distant colonies, such as Sri Lanka. Under Coen, the nutmeg groves on the island of Run were razed, a blow from which the Banda ecosystem never fully recovered.

After the VOC collapsed in the eighteenth century, the Dutch government took direct control, establishing an extensive colonial administration. They developed a small Javanese port into their capital, Batavia—modern-day Jakarta—and over three centuries forged what became known as the Dutch East Indies. Many islands, however, did not experience sustained Dutch presence until the late 1800s or early 1900s.

Timeline for Colonization of Indonesia

1511: Portuguese explorers arrived in the islands seeking to trade spices. They conquered the city of Malacca, thereby controlling the Straits. Months later, they sailed to eastern Indonesia in search of spices. [Sources: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006; Matthew Easton, Worldmark Encyclopedia of National Economies, Gale Group Inc., 2002; World Encyclopedia, Oxford University Press 2005; Clark E. Cunningham, International Encyclopedia of Marriage and Family, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

1596: The first Dutch ships arrived.

Seventeenth century: Seafaring Makasar people from South Sulawesi reached northern Australia, specifically the coastal region of Arnhem Land, in search of trepang (sea cucumbers) to sell to the Chinese. They interacted with Aboriginal people, leaving behind Makasar descendants and terminology.

1602: The Dutch East India Company (VOC) was formed as a private stock company to trade, establish treaties, and maintain troops in the Indies.

1610: By this time, the Dutch had acquired all of Portugal's holdings except for East Timor.

1641: The Dutch seized Malacca from the Portuguese and began establishing factories and plantations in Sumatra and Java. Jan Pieterszoon Coen, the governor-general of the Dutch East Indies, gained control of the spice trade in the Banda Islands and other areas of eastern Maluku.

1664: Atrocities in the Indies and ongoing trade battles with the Dutch resulted in an unexpected invasion of Manhattan (then a Dutch colony) by a British armada. This resulted in the Dutch being forced to swap Manhattan Island for the small Banda island of Run, a major turning point in American history.

1799: The Dutch East India Company declared bankruptcy and was replaced by Dutch government bureaucracy. The Dutch East India Company controlled the region during the 18th century.

1811: Java fell under the control of the British East India Company. As lieutenant governor, Thomas Stamford Raffles rediscovered Borobudur, which was buried under centuries of volcanic soil. He arranged for its excavation.

1815: Mount Tambora erupted on Sumbawa Island, obliterating an entire language group.

1825–1830: A period of conflict known as the "Java Wars" raged against the Dutch. The Netherlands also encountered opposition in western Sumatra from the Islamic leaders of the Minangkabau people.

1830: The Dutch instituted the Cultivation System, a forced labor program for producing coffee, sugar, indigo, pepper, tea, and cotton. This resulted in rice shortages and famines. The Cultivation System demanded a percentage of crops from all farmers, leading to a great commercial expansion of Dutch colonialism. This period secured the position and wealth of the elite Javanese priyayi in collusion with Dutch colonists.

1883: The Krakatoa volcano erupted in the sea west of Java, creating a tsunami that killed around 50,000 people.

1907–1911: The Borobudur excavation and restoration were completed under Dutch administration.

Modern History of Indonesia

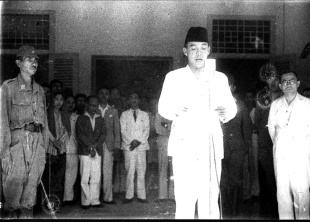

Japan occupied the islands from 1942 to 1945. Finally, on 17 August 1945, after the defeat of the Japanese in the Second World War, the Indonesian people declared their Independence through their leaders Sukarno and Hatta. Freedom, however was not easily granted. Only after years of bloody fighting did the Dutch government finally relent, officially recognizing Indonesia’s Independence in 1950.

Indonesia declared its independence shortly before Japan's surrender, but it required four years of sometimes brutal fighting, intermittent negotiations, and UN mediation before the Netherlands agreed to transfer sovereignty in 1949. A period of sometimes unruly parliamentary democracy ended in 1957 when President Sukarno declared martial law and instituted "Guided Democracy." After an abortive coup in 1965 by alleged communist sympathizers, Sukarno was gradually eased from power. [Source: CIA World Factbook =]

From 1967 until 1988, President Suharto ruled Indonesia with his "New Order" government. After rioting toppled Suharto in 1998, free and fair legislative elections took place in 1999. Indonesia is now the world's third most populous democracy, the world's largest archipelagic state, and the world's largest Muslim-majority nation. Current issues include: alleviating poverty, improving education, preventing terrorism, consolidating democracy after four decades of authoritarianism, implementing economic and financial reforms, stemming corruption, reforming the criminal justice system, holding the military and police accountable for human rights violations, addressing climate change, and controlling infectious diseases, particularly those of global and regional importance. =

In 2005, Indonesia reached a historic peace agreement with armed separatists in Aceh, which led to democratic elections in Aceh in December 2006. Indonesia continues to face low intensity armed resistance in Papua by the separatist Free Papua Movement.

Today, after six decades of freedom, Indonesia has become the third largest democracy in the world. Despite facing today’s global financial crisis, the country has managed to show positive economic growth, and is internationally respected for her moderate, tolerant yet religious stance in today’s global conflict among civilizations.

Road to Indonesian Independence and the Sukarno Era

1860: Publication of the novel Max Havelaar by former Dutch official Douwes Dekker, writing under the pen name Multatuli. The novel describes abuses by the combined Dutch and Javanese elite toward peasants.

1901: In response to criticism from within the Netherlands and other European nations, the Dutch created a more liberal Ethical Policy. At this time, the Netherlands controlled most of Indonesia.

1906: On September 20, the Dutch advanced on Denpasar in Bali. The entire royal family and their entourage marched toward the Dutch carrying only daggers. They were all shot or committed suicide. This day is remembered as Puputan, meaning "Ending."

1900–1930: Indonesian nationalism spread among various organized groups, including Muslims and Communists. Many of these groups joined the Indonesian Nationalist Party, which was formed by future President Sukarno.

1911: Raden Kartini's letters were published as a book in Holland. In 1920, the book was published in English as Letters of a Javanese Princess. It tells the story of a young Javanese woman's struggles with traditional values and European modern ideas.

1927: Sukarno, a university student who would later become president, founded the Indonesian National Party (PNI).

1942: The Japanese invaded Indonesia during World War II, driving out the Dutch.

1945: The Dutch return after the end of World War II, only to find Indonesians declaring independence. After news of Japanese surrender, Sukarno proclaimed Indonesia an Independent nation on August 17, 1945. Holland had attempted to regain control of Indonesia, but ceded it under international pressure, retaining only West Papua. Indonesia gained full sovereignty in 1949.

1949: Indonesia's independence is recognized. Sukarno and Muhammad Hatta became the first president and vice-president, respectively, and developed a policy called Guided Democracy.

1950s: Economic hardship and secessionist demands were met with authoritarian measures.

1963: Mt. Gunung Agung erupted in Bali killing more than 1,000 people.

1963: The Dutch began the process of ceding its last outpost, West Papua New Guinea to Indonesia. The region was then renamed Irian Jaya (Victorious Papua). In 1962, Indonesian paratroopers seized Netherlands New Guinea and, in 1969, it became part of Indonesia as Irian Jaya.

Suharto Era Timeline

1965: An attempted coup on September 30 left six generals and one child dead. General Suharto, the senior surviving officer, seized control and began consolidating power. The true circumstances behind the coup remain unclear.

1965–1967: Rumors that members of a communist women’s organization had mutilated the murdered generals helped spark a wave of violence. The army, aided by civilians, carried out mass killings of suspected communists and others. In Bali alone, as many as 80,000 people were killed; tens of thousands more died in North Sumatra and Java. Estimates place the nationwide death toll at over half a million.

1966: Suharto formally assumed control when Sukarno transferred presidential authority to him in March. Suharto was elected president in 1968 and quickly centralized power under the military-dominated “New Order.”

1967: Indonesia rejoined the United Nations. A new foreign investment law opened the way for large flows of international capital.

1974: OPEC-driven price increases brought a surge in oil revenues. Indonesia launched an ambitious development program, producing major gains in infrastructure, industry, healthcare, and education.

1975: Indonesia invaded newly independent East Timor with the tacit support of the United States and Australia, later declaring it an Indonesian province. Conflict and repression claimed more than 200,000 East Timorese lives before independence was finally achieved in 1999.

1978: Following severe inflation, the rupiah was devalued by 50 percent.

1980: Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s This Earth of Mankind was published in Indonesian, the first of the “Buru Quartet,” written during his imprisonment on Buru Island. Suharto banned these books. That same year, falling oil prices deeply shocked the economy.

1980s–1997: Suharto’s New Order remained firmly in control as political repression and corruption worsened. At the same time, sustained economic growth expanded Indonesia’s middle class.

1988: A series of economic reform packages began liberalizing trade, investment, and banking while curbing monopolies.

Ouster of Suharto and Afterwards

1997: The Asian financial crisis devastated Indonesia. The rupiah lost 80 percent of its value, and banks and businesses collapsed. Suharto resisted IMF-mandated reforms, and anger over corruption and cronyism fueled public outrage.

1998: Despite being re-elected to his seventh term, Suharto faced massive protests. Security forces killed four university students, triggering the “May Riots” in Jakarta. Government and commercial buildings were torched, and violent mobs targeted the Chinese Indonesian community—looting, burning, and committing atrocities. Three thousand buildings were destroyed. On May 21, abandoned by the military, Suharto resigned, handing power to Vice President B. J. Habibie.

1998–1999: Widespread violence gripped the country: Dayaks in Kalimantan killed migrants from Madura; Christian–Muslim conflict devastated Ambon; gangs controlled provincial streets; and clan warfare erupted in Sumba. Many regions descended into near-anarchy.

1999: In January, President Habibie announced that East Timor could vote on autonomy or independence, sparking renewed separatist sentiment across Indonesia and angering the military. After losing a parliamentary vote of confidence, Habibie withdrew from the presidential race. Following delayed and contentious elections, Abdurrahman Wahid became Indonesia’s fourth president on October 19, with Megawati Sukarnoputri as vice president. Under UN supervision, East Timor voted overwhelmingly for independence on August 30. As Indonesia withdrew, soldiers and militias burned much of the territory and forced thousands into West Timor.

2001: Allegations of corruption and incompetence led Parliament to impeach Wahid in July. Vice President Megawati Sukarnoputri succeeded him and was formally elected president.

2002: East Timor officially became independent. On October 12, a terrorist bombing at a Bali nightclub killed more than 200 people—mostly tourists—and destroyed an entire city block. Jemaah Islamiyah claimed responsibility, citing retaliation against U.S. Middle East policies. Additional attacks later struck Jakarta and Bali. Under Megawati, state authority weakened, conflicts spread, and military involvement in criminal rackets deepened public disillusionment.

2003: Scientists discovered Homo floresiensis, a small-bodied ancient hominin species, on Flores Island.

2004: In Indonesia’s first direct presidential election, voters chose Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (S.B.Y.), a retired general promising reform and stability, with Jusuf Kalla as vice president.

December 26, 2004: the Indian Ocean tsunami devastated Aceh, killing more than 200,000 Indonesians.

2005: After 31 years of conflict, Indonesian troops withdrew from Aceh. In exchange for disarmament and the abandonment of independence demands, Aceh gained substantial autonomy and a larger share of its oil and gas resources. The region incorporated sharia law into local governance. Press freedoms expanded, and modest judicial reforms began.

2006: On May 27, a 6.2-magnitude earthquake struck near Yogyakarta, killing more than 6,200 people and devastating the region. On July 17, a tsunami triggered by a 6.8-magnitude quake battered Java’s southwest coast, leaving as many as 1,000 dead and tens of thousands homeless.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Republic of Indonesia, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated December 2025