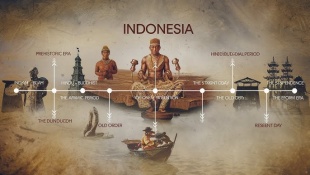

SHORT HISTORY OF INDONESIA

Ever since prehistoric times the Indonesian archipelago has been inhabited. Java Man or Homo erectus is the oldest known inhabitant here, having lived over a million years ago. Other more recent prehistoric species include the still disputed homo Floresiensis, or the Flores hobbits, dwarf people, who have also made these islands their home.

According to Lonely Planet: “The life of Indonesia is a tale of discovery, oppression and liberation, so it’s both impressive and perplexing to see the nation’s history displayed in a hokey diorama at Jakarta’s National Monument. The exhibit even includes Indonesia’s first inhabitant, Java Man (Pithecanthropus erectus), who crossed land bridges to Java over one million years ago. Java Man then became extinct or mingled with later migrations.

Historically, Chinese chronicles mention that trade between India, China and these islands was already thriving since the first century AD. The powerful maritime empire of Criwijaya with capital around Palembang in southern Sumatra, was the centre for Buddhism learning and was known for its wealth. It held sway over the Sumatra seas and the Malacca Straits from the 7th to the 13th. century. In the 8th -9th century, the Sailendra Dynasty of the Mataram kingdom in Central Java built the magnificent Buddhist Borobudur temple in Central Java, this was followed by the construction of the elegant Hindu Prambanan Temple built by the Civaistic king Rakai Pikatan of the Sanjaya line.

From 1294 to the 15th century the powerful Majapahit Kingdom in East Java held suzerainty over a large part of this archipelago. Meanwhile, small and large sultanates thrived on many islands of the archipelago, from Sumatra to Java and Bali, to Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Ternate and the Moluccas.

In the 13th century, Islam entered Indonesia through the trade route by way of India, and today, Islam is the religion of the majority of the population. Throughout history, traders have brought the world’s large religions of Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam to this archipelago, deeply influencing this country’s culture and way of life. Yet Indonesia was never conquered by India nor China, until Europeans came and colonized these islands.

Marco Polo was the first European to set foot on Sumatra. Later, in search for the Spice Islands the Portuguese and Spaniards arrived in these islands sailing around the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa. In 1596 the first Dutch vessels anchored at the shores of West Java after a long voyage. Over the next three centuries, the Dutch gradually colonized this archipelago until it became known as the Dutch East Indies.

But revolt against the colonizers soon built up throughout the country. The Indonesian youth, in their Youth Pledge of 1928 vowed together to build “One Country, One Nation and One Language: Indonesia”, regardless of race, religion, language or ethnic background in the territory then known as the Dutch East Indies.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JAVA MAN AND HOMO ERECTUS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

HOMO FLORESIENSIS: HOBBITS OF INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com

EARLIEST PEOPLE OF INDONESIA: NEGRITOS, PROTO-MALAYS, MALAYS AND AUSTRONESIAN SPEAKERS factsanddetails.com

OLDEST CULTURES IN INDONESIA AND PEOPLE THERE BEGINNING 10,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

FIRST INDONESIAN KINGDOMS: HINDU-BUDDHIST INFLUENCES, SEAFARING, TRADE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

SRIVIJAYA KINGDOM: HISTORY, BUDDHISM, TRADE, ART factsanddetails.com

MAJAPAHIT KINGDOM: HISTORY, RULERS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF ISLAM IN INDONESIA: ARRIVAL, SPREAD, ACEH, MELAKA, DEMAK factsanddetails.com

SPICES, TRADE AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA WHEN EUROPEANS FIRST ARRIVED: SPICES, POWERFUL STATES, DEALS, ISLAM factsanddetails.com

EARLY INDIANS, CHINESE AND ARABS IN INDONESIA: IBN BATTUTA, YIJING, ZHENG HE factsanddetails.com

EARLY EUROPEAN EXPLORERS IN INDONESIA: MARCO POLO, NICOLÒ DEI CONTI, MAGELLAN'S CREW factsanddetails.com

AGE OF EUROPEAN EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY DUTCH PERIOD IN INDONESIA AND THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY (VOC) factsanddetails.com

DUTCH EMPIRE: WEALTH, EXPLORATION AND HOW IT WAS CREATED factsanddetails.com

DUTCH, THE SPICE TRADE AND THE WEALTH GENERATED FROM IT factsanddetails.com

factsanddetails.com

NETHERLANDS INDIES EMPIRE IN THE 19TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER DUTCH RULE IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

RISE OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

Ignorance About Indonesia

Pankaj Mishra wrote in The New Yorker: “After India and China, Indonesia was the biggest new nation-state to emerge in the mid-twentieth century. Consisting of thousands of islands large and small, it sprawls roughly the same distance as that from Washington, D.C., to Alaska, and contains the largest Muslim population on earth. Yet, on our mental map of the world, the country is little more than a faraway setting for earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions. [Source: Pankaj Mishra, The New Yorker, August 4, 2014]

The political traumas of post-colonial Egypt, from Suez to el-Sisi, are far better known than the killing, starting in 1965, of more than half a million Indonesians suspected of being Communists or the thirty-year insurgency in Aceh Province. Foreign-affairs columnists, who prematurely hailed many revolutions at the end of the Cold War (Rose, Orange, Green, Saffron), failed to color-code the dramatic overthrow, in 1998, of Suharto, Indonesia’s long-standing dictator.

They have scarcely noticed the country’s subsequent transfers of power through elections (there was one earlier this month) and a radical experiment in decentralization. The revelation that, from 1967 to 1971, Barack Obama lived in Jakarta with his mother, a distinguished anthropologist, does not seem to have provoked broadened interest in Indonesian history and culture—as distinct from the speculation that the President of the United States might have been brought up a Muslim.

Themes in Indonesian History

Indonesia is incredibly diverse. According to one count there are 336 ethnic groups in Indonesia, speaking more 700 languages, spread among 13,000 islands. Because there are so many islands and on the islands the landscape is often very rugged, ethnic groups have developed in isolated spots. On the tiny island of Alor, for example, there are 140,000 people divided among 50 tribes, each of which speaks a distinct language or dialects that fall into seven distinct language groups.

Indonesia was molded from parts of Southeast Asia and Oceania. Traveling from one island to another is often like going from one country to another. Often there is little to unite the people on one island with another. After independence in 1949, “Unity in Diversity” was adopted as a national slogan and was pushed on Indonesians. The only modern nation comparable in terms of multiplicity of ethnic groups, languages and religions is the former Soviet Union. Through the development of a national language, standardized education and persistent government propaganda, Indonesia has become surprisingly unified.

Agriculture dominates the domestic economy. The Indonesians have traditionally practiced two types of agriculture: wet-land rice farming, and slash and burn agriculture, known as “ladang”. Many Indonesians have traditionally grown rice in the wet season and another crop in the dry season. The Dutch introduced efficient plantation agriculture which is still widely practiced. During colonial times 50 percent of the agriculture exports were produced on plantations that covered only 4 percent of the agricultural land. The plantations were of two types: ones in upland areas and ones in lowland fields. The Dutch-owned plantations were nationalized after independence. Many ultimately fell into the hands of Chinese businessmen and Suharto cronies.

To understand modern Indonesian politics, one must recognize the historical significance of power and leadership. Throughout history, controlling populations has been far more important than owning land. Subjects served rulers in exchange for protection, gifts, prestige, or simply peace. If a ruler was too harsh or failed to care for his subjects, many would simply move to a more favorable region. Thus, followers were flexible, and populations could suddenly shift. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Across the Indonesian islands, political authority typically operated according to a center–periphery model. Power radiated outward from a central court or leader, strongest at the core and diffusing toward the edges, where it overlapped with the influence of neighboring rulers. This model applied not only to major kingdoms but also to small village domains. A key measure of political strength in ancient Southeast Asia lay in a leader’s ability to attract and retain followers. As one analysis puts it, what Europeans might consider “real” political power—direct influence over others—depended on the belief that a ruler was favored by invisible spiritual forces. The more important question, therefore, was how long that supernatural favor would last.

Diversity in Indonesia

Indonesia is incredibly diverse. According to one count there are 336 ethnic groups in Indonesia, speaking more 700 languages, spread among 13,000 islands. Because there are so many islands and on the islands the landscape is often very rugged, ethnic groups have developed in isolated spots. On the tiny island of Alor, for example, there are 140,000 people divided among 50 tribes, each of which speaks a distinct language or dialects that fall into seven distinct language groups.

Indonesia was molded from parts of Southeast Asia and Oceania. Traveling from one island to another is often like going from one country to another. Often there is little to unite the people on one island with another. After independence in 1949, “Unity in Diversity” was adopted as a national slogan and was pushed on Indonesians. The only modern nation comparable in terms of multiplicity of ethnic groups, languages and religions is the former Soviet Union. Through the development of a national language, standardized education and persistent government propaganda, Indonesia has become surprisingly unified.

Most Indonesian islands are multiethnic, with both large and small groups forming distinct geographic enclaves. Towns within these enclaves are typically dominated by one ethnic group but also include members of various migrant communities. Larger cities may contain a wide mix of ethnicities, though some still have a clear majority group. [Source: Clark E. Cunningham, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Over centuries, regions such as West Sumatra or South Sulawesi have taken shape through the interplay of geography—rivers, ports, plains, and mountains—along with long histories of intergroup contact and political-administrative decisions. Some regions, including North Sumatra, South Sulawesi, and East Java, are ethnically diverse, while others, such as West Sumatra, Bali, and Aceh, are more culturally homogeneous.

Several areas—among them South Sumatra, South Kalimantan, and South Sulawesi—share a long-standing Malayo-Muslim coastal heritage that has shaped common cultural traits, from artistic traditions and clothing styles to religious life and systems of social hierarchy. In these same regions, upland or upriver communities often maintain distinct social, cultural, and religious identities, even as they are integrated—by choice or necessity—into the broader regional framework.

Many of these historical-cultural regions now correspond to modern government provinces, including the Malayo-Muslim coastal areas mentioned above. Others, like Bali, reflect older cultural patterns but do not map as neatly onto these administrative boundaries.

Kingdoms, Colonialism and Military Leadership in Indonesia

In the A.D. early centuries Indonesia came under the influence of Indian civilization through the gradual influx of Indian traders, as well as Buddhist and Hindu monks. By the seventh and eighth centuries, kingdoms closely connected with India had developed in Sumatra and Java. The spectacular Buddhist temples of Borobudur date from this period. Sumatra was the seat of the important Buddhist kingdom of Sri Vijaya from the 7th to the 13th century. In the late 13th century, the center of power shifted to Java, where the magnificent Hindu kingdom of Majapahit arose. For two centuries, it held sway over Indonesia and large areas of the Malay Peninsula. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Sumatra and Java and to a varying degree some of the other islands were under the control or influenced by a series of 5th to 15th century Malay and Javanese kingdoms (the Melayu, Sri Vijaya, Majapahit and Malacca). Indonesia has traditionally functioned operated under a system of sultans. Society has traditionally been divided between royalty, with its court and nobility, and landless peasants and government officials known as “prijaji”. The “prijaji” have traditionally been urban and there are several statuses.

Throughout Indonesian history, the military has played a prominent role in the nation's political and social affairs. A significant number of cabinet members have had military backgrounds, and active-duty and retired military personnel have occupied many seats in parliament. Commanders of the various territorial commands played influential roles in the affairs of their respective regions. With the inauguration of the newly elected national parliament in October 2004, the military no longer has a formal political role, though it retains significant political influence." [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale, 2008.]

European colonialism in Indonesia often functioned by co-opting local rulers. Colonial expansion makes the most sense when seen in relation to existing Indonesian political systems—sometimes aligning with them, sometimes disrupting them. A key historical insight is that both European and Indonesian historians have long placed the Dutch at the center of the story, a narrative that serves imperial and nationalist agendas but obscures the histories of Indonesia’s many societies. Nationalist histories typically portray Indonesians as passive victims of foreign domination, ignoring the fact that Indonesian elites frequently collaborated with outsiders. Europeans were also only one group among many traders who moved through the archipelago. In most regions, Dutch control did not become firmly established until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, though colonialism still produced profound changes in some areas and far-reaching consequences in Europe.[Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Indonesia’s Struggle to Forge an Identity

Pankaj Mishra wrote in The New Yorker: “This coexistence of the archaic and the contemporary is only one of many peculiarities that mark Indonesia as the unlikeliest of the nation-states improvised from the ruins of Europe’s empires after the Second World War. The merchants and traders of the Netherlands, who ruthlessly consolidated their power in the region beginning in the seventeenth century, had given the archipelago a semblance of unity, making Java its administrative center. The Indonesian nationalists, mainly Javanese, who threw the Dutch out—in 1949, after a four-year struggle—were keen to preserve their inheritance, and emulated the coercion, deceit, and bribery of the colonial rulers. But the country’s makeshift quality has always been apparent; it was revealed by the alarmingly vague second sentence in the declaration of independence from the Netherlands, which reads, “Matters relating to the transfer of power etc. will be executed carefully and as soon as possible.”[Source: Pankaj Mishra, The New Yorker, August 4, 2014]

“Indonesia, “As Elizabeth Pisani writes in her exuberant and wise travel book “Indonesia Etc.” , “has been working on that ‘etc’ ever since.” To be fair, Indonesians have had a lot to work on. Building political and economic institutions was never going to be easy in a geographically scattered country with a crippling colonial legacy—low literacy, high unemployment, and inflation. The Japanese invasion and occupation during the Second World War had undermined the two incidental benefits of long European rule: a professional army and a bureaucracy. In the mid-nineteen-fifties, the American novelist Richard Wright concluded that “Indonesia has taken power away from the Dutch, but she does not know how to use it.”

Wright invested his hopes for rapid national consolidation in “the engineer who can build a project out of eighty million human lives, a project that can nourish them, sustain them, and yet have their voluntary loyalty.” Indonesia did have such a person: Sukarno, a qualified engineer and architect who had become a prominent insurgent against Dutch rule. For a brief while, he formed—with India’s Jawaharlal Nehru and Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser—a kind of Holy Trinity of the post-colonial world. But Sukarno struggled to secure the loyalty of the country’s dissimilar peoples. In the service of his nation-building project, he deployed anti-imperialist rhetoric, nationalized privately held industries, and unleashed the military against secession-minded islanders. He developed an ideology known as Nasakom (an attempted blend of nationalism, Islam, and Communism), before settling on a more autocratic amalgam that he called Guided Democracy.

Headlines and Statistics Don’t Tell the Whole Story

Pankaj Mishra wrote in The New Yorker: “A much cited report by the McKinsey Global Institute claims that “around 50 percent of all Indonesians could be members of the consuming class by 2030, compared with 20 percent today.” It’s tempting to see Indonesia as a typical “traditional” society in which an increasingly individualistic middle class will bring about a secular and democratic nation-state. But Pisani’s knowledge of the country’s innermost recesses leads her to challenge the boosterish speculations of “pinstriped researchers at banks in Hong Kong, committees of think-tank worthies, or foreign journalists.” She counters McKinsey’s projections with some simple facts: “A third of young Indonesians are producing nothing at all, four out of five adults don’t have a bank account, and banks are lending to help people buy things, not to set up new businesses.” Meanwhile, the self-dealing activities of the country’s political and business élites—“raking in money from commodities, living easy and spending large”—do little to spur real economic growth. [Source: Pankaj Mishra, The New Yorker, August 4, 2014]

“She is equally dismissive of the ideologues who claim that Indonesia is in the ever-expanding evil empire of Islamic extremism. In much of Indonesia, religious practices are still syncretic. In Christian Sumba, she finds the islanders adhering to the ancient Marapu religion, “guided more by what they read in the entrails of a chicken than by what they read in the Bible.” Muslims show no sign of repudiating the wayang, the shadow-puppet theatre based on the Hindu epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Though it’s true that orthodox religion seems increasingly attractive to urban Indonesians, this is largely because religion “is a visible badge of identity which suits the need to clump together, so very pronounced in clannish Indonesia.”

A few fanatics attacking Christians and Muslim minorities, she argues, do not represent the majority, who seem indifferent to what other people believe. Religious political parties, faced with declining vote share, have moved pragmatically toward the center. However, a more hardheaded analysis would show that intolerance of religious difference has grown since the fall of Suharto and the advent of democracy. As Pisani admits, “Bigotry does produce votes.” In order to achieve electoral majorities, politicians have pulled all kinds of stunts—from rash promises of regional autonomy to legislation making women ride motorbikes sidesaddle and protests against Lady Gaga.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Republic of Indonesia, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated December 2025