IBAN

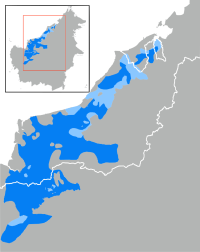

The Iban is a group of former headhunters that is found throughout Borneo but is particularly concentrated in the Malysian state of Sarawak. Also known as Dayaks and Dyak, they are the largest of Sarawak's ethnic groups, making up about 30 percent of the state's population. Sometimes erroneously referred to as the Sea Dayaks because of their skill with boats, they are actually an upriver tribe from the heart of Kalimantan. In the past, they were a fearsome warrior race renowned for headhunting and piracy. Traditionally, they worship a triumvirate of gods under the authority of Singalang Burung, the bird-god of war. Although now mostly Christians, many traditional customs are still practiced. The Sea Dayak name has also been attributed to a small group of Iban pirates on the Bornean coast in the 19th century. [Source: Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Iban have traditionally lived along the mid levels hills of Borneo, but during the last 200 years, half have moved to the delta plains. Between the 1960s and 1990s 20 percent of Sarawak's Iban population moved into the state's urban centers and more have done so since then. The origin of the name "Iban" is uncertain. Early scholars believed it was originally a Kayan term, "hivan," meaning "wanderer." The use of the name by Iban groups in closer association with the Kayan lends support to this theory. However, other Iban from Sarawak's First and Second Divisions used the name "Dayak" and still consider "Iban" to be a borrowed term today. ~

According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Iban population is 834,000, with 798,000 in Malaysia, mostly in Sarawak, up from 657,700 in 2004. There were approximately 400,000 Iban in Sarawak in 1989 and 368,208 in 1980. Reliable figures for Kalimantan in the Indonesian part of Borneo from that time are unavailable. [Source: Joshua Project and ~]

Iban language , known as Iban,is distinct from other Bornean languages and shares some number of words with the Malay language but it is not a Malay dialect. Iban is widely spoken throughout Sarawak, alongside Malay, which has long served as the lingua franca of the archipelago.[Source: P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009^^]

Although Iban is commonly used across the region, there are regional and district-level variations in accent and speech. For instance, Iban spoken in the Miri–Bintulu area differs in accent from that spoken in the Kuching–Bau region. Despite these dialectal differences, speakers of Iban generally understand one another without difficulty.

Iban. Before the introduction of formal education in Sarawak, the language had no written form, and knowledge was transmitted orally from one generation to the next. Important events were preserved through memory, often narrated through berenong, a tradition of singing songs that conveyed history and experience. As with many indigenous groups in Borneo, Iban personal names consist of two elements: a given name and the father’s name. It is customary to insert the word anak, meaning “child of,” between the two. For example, a person named Ugat, whose father is Muli, would be known as Ugat anak Muli. ^^

RELATED ARTICLES:

IBAN PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, VILLAGES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS IN THE 1840s factsanddetails.com

DAYAK LIFE AND CULTURE: FAMILY, ART, FOOD, LONGHOUSES factsanddetails.com

DIFFERENT DAYAK GROUPS: KENYAH, KAYAN, MONDANG factsanddetails.com

NGAJU DAYAKS: LIFE, CULTURE, RELIGION, ART factsanddetails.com

PENAN: RELIGION, CULTURE, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

PENAN LIFE AND SOCIETY: FOOD, CUSTOMS, VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

PENAN AND THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

TRIBAL PEOPLE OF BORNEO: LONGHOUSES, SAGO, ART factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

KALIMANTAN (INDONESIAN BORNEO): GEOGRAPHY, DEMOGRAPHY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL AND EASTERN SARAWAK (NORTHERN factsanddetails.com

Iban History

The Iban trace their origin to the Kapuas Lake region of Kalimantan. Regarded as an aggressive group, they expanded out of their homeland towards the coast, fighting with other tribes and taking heads and slaves. The enslavement of captives contributed to the necessity of moving into new areas. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Iban were well-established in what is now the First and Second Divisions of Sarawak, and some had settled in the vast Rejang River valley. [Source: Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

When they first encountered the British they responded by moving inland. After the establishment of the Brooke Raj in Sarawak in 1841, thousands of Ibans migrated to the middle and upper regions of the Rejang. By the end of the 20th century, they had entered all remaining divisions. After Malaysia became independent they expanded throughout Sarawak of living side by side with other ethnic groups. In recent years they have abandoned their longhouses and most live like ordinary Malays. ~

Traditionally, the major causes of conflict among the Iban were land boundaries, alleged sexual improprieties, and personal affronts. The Iban are a proud people who traditionally have not not tolerated insults to persons or property. The main source of conflict between the Iban and non-Iban, particularly with other tribes with whom the Iban competed, was the control of the most productive land. As recently as the early 20th century, the conflict between the Iban and the Kayan in the Upper Rejang region was severe enough to prompt the second Rajah to dispatch a punitive expedition and forcibly expel the Iban from the Balleh River. ~

Rapid economic development has exacerbated by the high rate of rural-urban migration among the Iban. Many longhouses are often empty except during the Gawai Dayak and Christmas holidays. Many Iban return to their longhouses for special occasions. ^

Iban Headhunting

At one time an Iban standing in the community was determined by the number of heads he had taken but some sources have said the Iban only hunted heads in self defense. The Iban hunted heads up until World War II. In Brunei, the head of their last victim, a Japanese soldier, is occasionally brought out to show foreign guests. The origin of headhunting among the Iban, some anthropologists believe, is tied to mourning rules given by a spirit. One of them reads: “The sacred jar is not to be opened except by a warrior who has managed to obtain a head, or by a man who can present a human head, which he obtained in a fight; or by a man who has returned from a sojourn in enemy country. [Source: Iban Cultural Heritage website ==]

Among the war (ngayau) regulations followed by the Iban are: 1) If a warleader leads a party on an expedition, he must not allow his warriors to fight a guiltless tribe that has no quarrel with them. 2) If the enemy surrenders, he may not take their lives, lest his army be unsuccessful in future warfare and risk fighting empty-handed war raids (balang kayau). 3) The first time that a warrior takes a head or captures a prisoner, he must present the head or captive to the warleader in acknowledgement of the latter’s leadership. 4) If a warrior takes two heads or captives, or more, one of each must be given to the warleader; the remainder belongs to the killer or captor. 5) The warleader must be honest with his followers in order that in future wars he may not be defeated (alah bunoh). ==

Charles Hose, an Englishman stationed on Borneo as the Resident Magistrate during British Imperial rule in the early 20th century, described Iban headhunting in his book, “The Pagan Tribes of Borneo”, published in 1912: “It is clear that the Ibans are the only tribe to which one can apply the epithet head-hunters with the usual connotation of the word, namely, that head-hunting is pursued as a form of sport.” He also said these same people “are so passionately devoted to head-hunting that often they do not scruple to pursue it in an unsportsmanlike fashion.”[Source: discover-malaysia.com]

Hose believed the Ibans probably “adopted the practice [of headhunting] some few generations ago only... in imitation of Kayans or other tribes among whom it had been established,” and that “the rapid growth of the practice among the Ibans was no doubt largely due to the influence of the Malays, who had been taught by Arabs and others the arts of piracy.” As their own areas became overpopulated, they were forced to intrude on lands belonging to other tribes to expand their own land-trespassing which could only lead to death when violent confrontation was the only means of survival.

On why the practice of headhunting existed, Hose wrote: “That the practice of taking the heads of fallen enemies arose by extension of the custom of taking the hair for the ornamentation of the shield and sword-hilt,” and that: “The origin of head-taking is that it arose out of the custom of slaying slaves on the death of a chief, in order that they might accompany and serve him on his journey to the other world.”

Iban Religion

Over the years, many Iban have become Christian, while others have become Muslim. According to the Christian group Joshua Project most Iban either follow their traditional animist beliefs and adhere to them to some degree and 10 to 50 percent are Christians, with many of these being Protestant Evangelicals. Traditional Iban animist beliefs, hold that all beings possess a soul. This belief system underlies many Iban rituals. They revere mythical and legendary heroes and deities. In the past, as with many other native groups in Sarawak, the Iban relied on dreams and bird augury — particularly that of the banded kingfisher, rufous piculet, and maroon woodpecker — for guidance before undertaking any activity. For example, they would observe the behavior of these birds and other animals, reptiles, and insects before farming, hunting, or engaging in trade. They would not proceed with any of these activities if they interpreted these natural events as bad omens. [Source: P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Iban life and religion are intricately intertwined. The Iban believe that “nothing happens without a cause” and that their everyday activities are directed by the bird-god Sengalang Burong, who issues messages through his seven son-in-laws. In their myth crickets determine the sex of children, trees talk and pots cry out to be hugged. [Source: Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Iban religion reflects a holistic worldview in which all experiences—both waking and dreaming—are significant. It is grounded in an all-encompassing sense of causality, shaped by the conviction that nothing occurs without a cause. This pervasive religious outlook heightens awareness of every dimension of existence and gives rise to an elaborate otherworld, Sebayan, where all things possess the potential for perception, intention, and action. In Iban beliefs and narratives, trees speak, crotons walk, macaques become incubi, jars lament neglect, and the sex of a human fetus is determined by a cricket—the transformed form of a god.

Although the gods dwell in Panggau Libau, a distant and sacred realm, they are invisible yet ever-present. Iban cosmology allows constant interaction between mortals and supernatural beings in all matters of importance. Alongside benevolent deities, the Iban also believe in and fear numerous malevolent spirits. These spirits can be understood as projections of the anxieties and pressures of everyday life, such as threatening paternal authority, vengeful maternal forces, parasitic dependents, or the fear of becoming lost in the forest. To preserve health and well-being, the Iban seek to live in accordance with customary law, avoid taboos, and present offerings and animal sacrifices to maintain harmony with the spiritual world.

Iban Religious Practitioners and Ceremonies

There are three kinds of Iban religious practitioners: 1) bards, responsible for reciting myths, histories and genealogies; 2) augurs, who are involved in presiding over rituals involving things like agriculture and traveling; and 3) shaman, who work primarily as healers. For some rituals all three work together. Iban religioous practitioners are highly respected men who are capable of recalling and adapting chants that go on for hours. They are employed in rituals deemed important such as those related to farming and traveling. Shaman are consulted for unusual or persistent ailments. [Source: Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Iban Religious ceremonies and rituals (gawa, gawai) generally fall into four categories 1) agricultural festivals; 2) healing rituals; 3) ceremonies connected with head hunting; and 4) rituals of the dead. Most Iban perform rituals from the first two categories. In the upper Rejang, ceremonies to honor warriors have become more important, and rituals for the dead have become more elaborate in the first and second divisions of Sarawak. ~

Illness, Death and Afterlife. The Iban believe health is generally associated with the condition of the seven souls recognized by the Iban and illness is sometimes caused by malevolent spirts who drive the soul from the body. If this happens a shaman is brought in to retrieve the soul. If the soul is not retrieved a person dies. The boundaries between life and death are vague. At death, the soul must be instructed by a shaman to move on to Sebayan, world of unimaginable pleasure. After death the primary soul crosses the “Bridge of Anxiety” to Sebayan. After a brief stay the soul becomes a spirit which later returns to the earth in form of rice-nourishing dew. In this form, it reenters the realm of the living by nourishing the growing rice. When the rice is ingested, the soul's cycle is completed by its return to human form. The Gawai Antu festival, or Festival of the Dead, may be held anywhere from a few years to 50 years after the death of a community member. The main part of the festival occurs over a three-day period but takes months or even years to plan. The festival primarily honors all the community's deceased, who are invited to participate in the rituals. The festival illustrates the dependence of the living and the dead on each other. ~

Celebrations, Festivals and HolidaysIn addition to celebrating major Malaysian holidays such as Christmas, Hari Raya, and Chinese New Year, the Iban people of Sarawak celebrate various religious festivals known as Gawai. Several gawai are very important in Iban society. The most important ones are Gawai Batu, Gawai Memali Uma (rice cultivation), Gawai Nyintu Orang Sakit (health and longevity), Gawai Kenyalang (warfare and bravery), and Gawai Antu (a festival for the dead). Rituals for these festivals include offerings of food, chanting, and incantations by ritualists. The Sarawak government sets aside two or three days each year to celebrate the most significant and interesting festival, the Gawai Dayak. This thanksgiving celebration marks the end of the harvest season and the beginning of the next farming cycle. It is an occasion to seek blessings from the gods and spirits for the new year. Besides observing certain rituals, the festival involves merriment, drinking tuak (locally brewed rice wine), and displaying elaborate traditional costumes. [Source: P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Iban Culture and Folklore

In villages without televisions or cinemas, entertainment has traditionally centered on music and dance. After a day of labor, longhouses were often filled with the sound of gongs, except during periods of mourning. In their spare time, Iban traditionally made pottery, producing clay cooking pots, as well as a wide range of handicrafts such as baskets, mats, and caps. These are crafted from rattan, bamboo, nipah palm, bemban, screw-pine, and other plants native to their environment. [Source: Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

The Iban have produced one of the richest bodies of folklore in the world, comprising more than a dozen forms of epic, myth, and ritual chant. The Iban do not possess a strong written literary tradition. Instead, their stories, myths, and legends have long been transmitted orally from one generation to the next, with systematic efforts to record and preserve them only beginning in recent times.

Iban Myths, Legends, and Stories recount headhunting raids of the past, as well as systems of augury in which divine guidance is sought through natural signs, especially the behavior of birds and other animals. While the Iban did not practice human sacrifice, headhunting was once associated with ideals of bravery, courage, leadership, and success in warfare. Folklore therefore celebrates heroic exploits, the founding of new settlements, and victories in conflict. The men and women associated with these achievements were honored in life and continue to be remembered in ritual chants, legends, and stories.

Traditional Sports and Games include cockfighting and spinning tops. In the past cockfighting was held during an annual season, though it was later banned due to gambling. Beyond its recreational aspect, cockfighting carried symbolic meaning, representing supernatural contests between rival forces. Other activities, such as soccer, have become increasingly popular. Physical contests such as individual and team tug-of-war (batak lampong), arm-wrestling, and long jumping are commonly played in the open space in front of longhouses and are often featured during festivals and communal celebrations.

Iban Music and Dance

Many musical instruments used by indigenous peoples in Sarawak are made from bamboo, rattan, and local woods. The most important Iban musical instrument is called a “engkerumong” which is a set of bronze gongs haug from ropes hanging from a stretched wooden frame which are struck with a wooden mallet. It is an ancient instrument produced in many sizes and styles and used in both musical and ceremonial contexts. Another widely used instrument is the ketebong, a slightly hourglass-shaped single-headed drum carved from a tree trunk. Gong and ketebong music accompanies a variety of dances, including the ngajat (traditionally performed by women), warrior dances, and sword dances. [Source: Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Men and women of all ages take part in dancing, which may include sword dances, castanet dances, saucer dances, war dances, and shield dances. These gatherings provide opportunities to display skill, grace, and vitality. The Warrior Dance is a traditional dance of the Iban people. This dance is usually performed during Gawai Kenyalang or 'Hornbill Festival'. Reputedly the most fearsome of Sarawak's headhunters, the tribe's victorious warriors were traditionally celebrated in this elaborate festival. Wearing an elaborate headdress and holding an ornate long shield, the male warrior dancer performs dramatic jumps throughout this spellbinding dance. [Source: Malaysian Government Tourism]

Iban Tattoos, Body Adornment and Art

Men have traditionally covered their bodies with tattoos and men and women wore iron rings in their lobes up to six inches in diameter. Even when the rings were removed the pierced earlobes drooped almost to their shoulders. Some Iban had a tattoo of hook tied to a bamboo raft on their leg to keep crocodiles from attacking. The reasoning goes that when the crocodile sees the hook it won't bite. [Source: Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr., “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Iban artistic traditions also include weaving, woodcarving, metalworking, music, and dance. Iban women are renowned for their skill in weaving on the backstrap loom, producing blankets, textiles, mats, and baskets, while men are noted for their craftsmanship in woodcarving and their mastery of metalworking techniques, particularly the use of piston bellows.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains some wood Iban tuntun pig-trap sticks. One probably probably made in the Sarebas-Krian region in the Late 19th-early 20th century measures 53.3 centimeters (21 inches). Eric Kjellgren wrote: Created intentionally to please the eye, tuntun, or pig-trap sticks, are unique to the Iban people of Borneo.The beauty, design, and detail sculptural refinement of tuntun were believed to increase their effectiveness. When hanging in the longhouse, a tuntun was expeded to attrad the attention of passersby who, if impressed with its artistic qua lities, would take it down and admire it. A tuntun that failed to attrad human visitors was thought to be equally ineffective at attracting game. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The figures on tuntun are typically in the act of calling their quarry, with their mouths wide open and their hands often cupped on either side, as if to amplify the sound. Each portrays a specific spirit associated with pigs or pig hunting. The present work depicts Raja Laut, a being unique to the Iban of the Sarebas and Krian regions, who formed close ties with neighboring Malay peoples, who were Muslims. Often called upon by the lban to help resolve internal disputes, Malay leaders were admired for their powers of persuasion. Recognizable by his fiat-topped hajji's hat (worn by men who had made a pilgrimage to Mecca) and the small stool on which he sits, Raja Laut is depicted as a Malay man who, with his eloquence, is able to convince an animal to enter the trap.

The fact that Malays, as Muslims, did not eat pork was thought to make the figure even more effective, reassuring the guileless pig that the spirit meant no harm as it lured the animal to its doom. For reasons that are unclear, figural tuntun were made only by Iban groups living along the Sarebas, Krian, and Batang Lu par river systems as well as the upper Kapuas River in the Malaysian state of Sarawak and across the watershed in the Indonesian province of Kalimantan Barat

Iban Textiles and Ceremonial Clothes

One of the most valued expressions of Iban cultural heritage is the pua kumbu, a handspun textile made from locally grown cotton known as taya. The creation of pua kumbu demands exceptional skill, technical mastery, and imaginative design, and the knowledge required is traditionally passed from mother to daughter. Each stage of production—from preparing the cotton yarn and tying the threads to dyeing and selecting motifs—requires precision and experience. Pua kumbu is used for women’s bidang, men’s kelambi, and as blankets.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains an Iban pua' kumbu' (ceremonial cloth). Made of cotton probably in the 18th century, it measures 240 centimeters (94 inches) in lenth. Eric Kjellgren” The spectacular pua' (ceremonial cloths) of the Iban people are masterworks of the weaver's art. Created exclusively by women, the variety seen here, known as a pua' kumbu ', is produced using the ikat technique-an exacting process that involves tying and dying the intricate and colorful patterns into the threads before they are placed on the loom and woven. In contrast to the many indigenous peoples in Borneo and elsewhere in Island Southeast Asia who have hereditary social classes, the lban were essentially egalitarian, and an individual's social status was determined by personal achievement. Each sex pursued its own path to social prestige. Until the early twentieth century, an Iban man achieved status through his prowess as a warrior and headhunter. A woman's status was, and among many contemporary Iban still is, determined by her achievements as a dyer and weaver.[Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Women's accomplishments in creating powerful ceremonial textiles were seen as equivalent to men's exploits in war. As the late Iban master weaver Iba Anak Temenggong Koh eloquently put it: "Men take heads, we women make cloth."Formerly, an Iban man was ideally expected to take a head, and a woman to weave a pua', before marrying. The act of applying the mordant to the threads of a textile, which allowed them to absorb the deep red dye for which lban textiles are renowned, was referred to as kayau indu ' (the women's warpath), a term often used more broadly to refer to the entire weaving process. Like warfare, weaving was a dangerous and potentially life-threatening activity. The patterns of pua ' were supernaturally powerful and the various designs were ranked according to their potency.

Whether ancient or innovative, all pua' patterns are said to have been originally revealed in dreams in which the weaver is visited by ancestral women, often the two legendary sisters Kumang and Lu long, who teach her the complex and beautiful designs. Novice weavers begin with the simplest designs and over the course of many years seek to master the most powerful patterns, which, if not properly executed, will weaken a woman's ayu (vital force), causing her to sicken and die. Conceived and executed with near flawless precision, the pattern on this magnificent pua' is among the highestranking and most supernaturally powerful of all. The pattern is known as buah sempuyong (skull basket) — a reference to the sempuyong, a bamboo basket formerly used to hold newly captured enemy heads. Earlier scholars believed that the names of pua' patterns derived from their imagery and sought to interpret individual motifs as stylized representations of the object or animal mentioned in the pattern name, but more recent research indicates that the names were simply somewhat arbitrary designations used to distinguish the various patterns. Hence the name "skull basket" is probably a metaphorical reference to what was formerly the most important role of pua' cloths, the ceremonial reception of enemy heads, rather than to any aspect of the pattern 's imagery.

Although the role of pua' in head-hunting has long ceased, they retain their status as the most important of all Iban ceremonial textiles. Today as in the past they form an essential and ubiquitous element in all major gawai (ceremonies), where they demarcate sacred spaces, shade sacrificial animals, serve as cloths for the presentation of offerings, and fill a multitude of other purposes. During gawai large numbers of pua' are often used to decorate the longhouse or other ceremonical structures. These displays honor both human guests and visiting deities, who are said to take delight in viewing the beautifully patterned textiles.

Iban Activism over Anti-Logging and Dams

The issue of land rights is one of the most pressing social problems facing the Iban people of Sarawak. The rapid economic development currently taking place in Sarawak requires the Iban to give up their land for development. This has put the Iban and other ethnic communities in a dilemma. In order to be involved in "progress" and "development," they must give up their land, which is often then logged and developed into agricultural plantations. [Source: P. Bala, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

The Iban have lost their land to logging, palm oil plantations and dams. They have been involved in land rights protest and court cases. In the past 40 years or so more than a quarter of all Iban have moved to urban areas in Sarawak. The Bakun Dam is a major issue with the Iban. See RAINFORESTS, TIMBER AND DEFORESTATION IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

In October 2009, AFP reported, “Malaysian police said they had arrested a native leader who set up roadblocks in Borneo to stop a logging firm from encroaching on their ancestral land. Ondie Jugah, 55, from the Iban indigenous group, was among a group of 10 people who have mounted a blockade since early this week in the interior of eastern Sarawak state, on Borneo island. Police said Ondie was detained late Friday after he refused to remove the blockade, following complaints filed by the logging company. "We directed him to open up the road but he refused, so we have to take him back to facilitate investigation," a senior police official from the local Kapit district, who did not want to be named, told AFP. [Source: AFP, October 23, 2009]

Ondie's son, Anthony, urged the police to release his father, saying they were merely protecting their home."They (the logging company) want to destroy our land and did not want to compensate us," the 29-year-old told AFP. Nicholas Mujah, secretary general of indigenous rights group Sarawak Dayak Iban Association, condemned the arrest as a form of "harassment" of the vulnerable group and demanded the authorities respect native land rights.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026