NUSA TENGGARA

Nusa Tenggara is a string of islands that extend to the east of Bali and continues in a southeast curve towards Australia. The main islands are (from west to east) Lombok, Sumbawa, Komodo, Flores, Sumba, and Timor. Also known as the Lesser Sundas or Lesser Sunda Islands, Nusa Tengarra is the driest part of Indonesia. Parts of the islands have been denuded by slash and burn agriculture and brush fires. As one travels eastwards the climate get drier and drier and some land areas are covered by open savannah. The 300-meter-deep channel that runs between Bali and Lombok extends northwards and divides Kalimantan and Sulawesi and marks the Wallace Line, with different species of animals living on each side.

The largest islands in Nusa Tengarra are Sumba, Flores and Timor. Bali and Nusa Tenggara account for 4.6 percent of Indonesia’s land and 5.3 percent of its population. The region is poorer than other parts of Indonesia. Corn and taro are grown in the dryer areas rather than rice. Many ethic groups live in the region, particularly on Flores and Alor. Many of the people are Christians. As one travels eastwards the climate get drier and drier and some land areas are covered by open savannah.

The northern parts of some of the islands are mountainous and lush with tall trees and shrubs. The south, on the other hand is arid and covered by savannas. Large Asian mammals are absent and replaced in some cases by marsupials, lizards, cockatoos and parrots. The difference becomes more pronounced as one moves further east, where dry seasons are more prolonged and corn and sago are staple food, instead of rice.

The population of East Nusa Tenggara consists predominantly of Sasak people (approximately 56 percent), followed by Bimanese (14 percent), Balinese (12 percent), Sumbawanese (8 percent), Dompu (3 percent), and Javanese (2 percent). Arab, Bugis and Chinese also live in this area. Islam is the dominant religion, practiced by nearly 97 percent of the population. Most Sasak people are Muslim and they value modesty. Major groups in West Nusa Tenggara include the Atoni (22 percent), Manggarai (15 percent), Sumba (12 percent), Tetum (9 percent), Lamaholot (8 percent), Rotenese (5 percent), and Lio (4 percent), About 90 percent are Christians and less than 10 percent are Muslims.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

SASAK PEOPLE OF LOMBOK: HISTORY, CULTURE, LIFE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

LOMBOK: HISTORY, PEOPLE, TOURISM, GETTING AROUND factsanddetails.com

SUMBAWA: SIGHTS, BEACHES, TAMBORA factsanddetails.com

KOMODO AREA: TOURISM, SIGHTS, NATIONAL PARK factsanddetails.com

TIMOR

ATONI PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

KÉDANG PEOPLE OF EASTERN INDONESIA: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

ROTENESE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

SUMBANESE: LIFE, RELIGION, TRADITIONAL HOUSES factsanddetails.com

SUMBA CULTURE: IKAT, CEREMONIAL CLOTHES, PASOLA HORSE FIGHTS factsanddetails.com

SUMBA: SIGHTS, TOURISM, VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

Wallace Line

Indonesia’s, Asia's and Oceania's flora and fauna is divided by the “Wallace Line”, an invisible biological barrier described by and named after the 19th-century British naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace. Running along the water between the Indonesia islands of Bali and Lombok and between Borneo and Sulawesi, it separates the species found in Australia, New Guinea and the eastern islands of Indonesia from those found in western Indonesia, the Philippines and the Southeast Asia.

The Wallace Line marks a point of transition between the flora and fauna of Western and Eastern Indonesia and acts as the western boundary of West Nusa Tenggara, which includes the islands of Lombok and Sumbawa. After all these centuries, the wildlife remains nearly unchanged.In Indonesia the Wallace Line runs between Bali and Lombok, continuing north between Kalimantan and Sulawesi. West of the Line, vegetation and wildlife are Asian in nature, whereas east of the Line, these resemble those of Australia. The animals of Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Java west of the Wallace Line are similar to those found on Peninsular Malaysia.In Sulawesi, the Maluku Islands, and Timor, east of the Wallace Line, Australian types begin to occur. Bandicoot, a marsupial, is found in Timor. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007; Ministry of Tourism and Creative Economy, Republic of Indonesia]

For more information on the Wallace Line See BIODIVERSITY IN SOUTHERN ASIA: WALLACE LINE, HOTSPOTS, RARE SPECIES factsanddetails.com

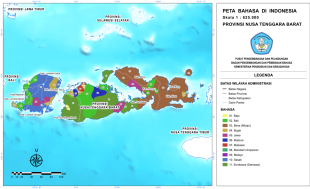

West Nusa Tenggara

West Nusa Tenggara is a province of Indonesia located in the western part of the Lesser Sunda Islands. The province covers an area of 19,890 square kilometers (7,680 square miles) and consists primarily of two major islands—Lombok and Sumbawa—along with several smaller islands. Lombok, situated in the west, is smaller in size but significantly more densely populated, while Sumbawa, to the east, is much larger in area yet more sparsely populated. The provincial capital and largest city is Mataram, located on Lombok Island. West Nusa Tenggara shares maritime borders with Bali to the west and East Nusa Tenggara to the east. Nusa Tenggara. [Source: Wikipedia]

Geographically, West Nusa Tenggara province is characterized by a combination of coastal lowlands and mountainous terrain. Flat coastal areas dominate much of western and southern Lombok, while the island’s interior is marked by rugged highlands, including Mount Rinjani, the province’s highest peak at 3,726 meters (12,224 feet). Mount Rinjani is an active volcano and one of Indonesia’s most prominent natural landmarks and tourist attractions. On Sumbawa Island, the landscape is more varied, featuring steep hills, mountain ranges, and extensive dry grasslands, particularly in the eastern regions.

As of mid-2024, West Nusa Tenggara has an estimated population of approximately 5.73 million people, making it the 13th most populous province in Indonesia. Population density averages about 288 people per square kilometer, with the majority of residents concentrated in coastal areas and urban centers, especially around Mataram. The province is culturally diverse, with the Sasak people forming the majority on Lombok Island, while Samawa and Mbojo communities predominate on Sumbawa. These groups continue to preserve distinctive local traditions, languages, and artistic practices.

The natural environment of West Nusa Tenggara is one of its major attractions. The province is renowned for its beaches, including Kuta Beach in Lombok and Lakey Beach in Sumbawa, both internationally recognized surfing destinations. Off the northwest coast of Lombok lie the Gili Islands—Gili Trawangan, Gili Air, and Gili Meno—which are among Indonesia’s most popular tourist destinations, celebrated for their clear waters, coral reefs, and marine biodiversity. In addition to coastal tourism, West Nusa Tenggara is rich in cultural and historical heritage. Notable sites include Sade Village in Lombok, where traditional Sasak architecture and ways of life are still maintained, and historical palaces associated with the former Bima Sultanate on Sumbawa Island. These cultural landscapes, together with the province’s natural features, contribute to West Nusa Tenggara’s significance as both a cultural and ecological region of Indonesia.

Demographically, the province is ethnically diverse. According to available data, the population consists predominantly of Sasak people (approximately 56 percent), followed by Bimanese (14 percent), Balinese (12 percent), Sumbawanese (8 percent), Dompu (3 percent), and Javanese (2 percent), among others. Islam is the dominant religion, practiced by nearly 97 percent of the population, with Hinduism, Christianity, Buddhism, and other faiths present in smaller proportions. Indonesian is the official language, while regional languages such as Sasak, Bimanese, Sumbawa, Balinese, and Ampenan Malay are widely spoken in daily life.

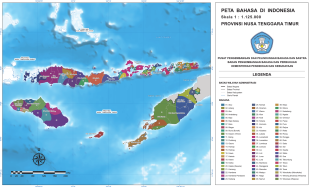

East Nusa Tenggara

East Nusa Tenggara is the southernmost province of Indonesia. It occupies the eastern portion of the Lesser Sunda Islands, bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Flores Sea to the north. The province covers a total land area of 47,238 square kilometers (18,240 square miles) and consists of more than 500 islands. The largest among these are Sumba, Flores, and the western part of Timor, the latter sharing a land border with the independent nation of East Timor (Timor-Leste). Administratively, East Nusa Tenggara is divided into twenty-one regencies and one regency-level city, Kupang, which serves as both the capital and the largest urban center.

East Nusa Tenggara embraces over 550 islands, but it's dominated by three main islands, Flores, Sumba and Timor. The arid landscape of eastern and southeastern Nusa Tenggara is the result of hot, dry winds blasting in from Australian continent. In many coastal areas little rain falls during most of the year. The islands between Sumbawa and Timor are crowded with volcanoes and mountains. Mt Sirung in East Nusa Tenggara erupted in May 2004. Hundreds of people were forced to evacuate their homes. Plantations at the base of the mountain were said to have dried up.

East Nusa Tenggarais renowned for its striking natural landscapes and protected areas. Notable destinations include Komodo National Park, home to the Komodo dragon; the coastal town of Labuan Bajo; Lake Kelimutu with its tri-colored volcanic crater lakes; and numerous beaches scattered across the islands. East Nusa Tenggara is also culturally rich, characterized by a wide diversity of ethnic groups, languages, and traditions. Distinctive cultural expressions include ikat weaving practiced across many islands and ritual ceremonies such as Pasola in Sumba.

The islands of Nusa Tenggara are divided into several regions with distinct languages and traditions. Predominantly Catholic and heavily influenced by the Portuguese, eastern Nusa Tenggara displays remnants of its strong European cultural heritage, like the Easter procession held in Larantuka and royal regalia of the former king in Maumere. As of mid-2024, East Nusa Tenggara has an estimated population of approximately 5.72 million people, ranking 12th among Indonesian provinces. With a population density of about 121 people per square kilometer, it is relatively sparsely populated compared to many other regions of Indonesia. The highest elevation in the province is Mount Mutis, which rises to 2,427 meters (7,962 feet) above sea level.

Ethnically, the population is highly diverse. Major groups include the Atoni (22 percent), Manggarai (15 percent), Sumba (12 percent), Tetum (9 percent), Lamaholot (8 percent), Rotenese (5 percent), and Lio (4 percent), among others. Indonesian is the official language, while Kupang Malay serves as a widely used lingua franca. Numerous regional languages and dialects—such as Tetum, Uab Meto, Sikka, Lamaholot, Rotenese, Li’o, and others—continue to be spoken across the province, reflecting East Nusa Tenggara’s deep linguistic and cultural diversity. Religion in East Nusa Tenggara (December 2023): Roman Catholic (53.7 percent); Protestantism (36.2 percent); Islam (9.45 percent); Marapu and others (0.56 percent); Hinduism (0.10 percent) and Buddhism (0.01 percent),

History of Nusa Tenggara

Flores in Nusa Tengarra is the home of Homo floresiernsis, the Hobbit-like hominids that lived between 190,000 and 12,000 years ago. Research at Liang Bua Cave on Flores Island revealed fossils of Homo floresiernsis. Archaeological evidence, including complex stone sarcophagi, decorated stoneware, machetes, and axes, suggests that West Nusa Tenggara was originally inhabited by populations originating from Southeast Asia. These prehistoric remains indicate an early and well-established human presence with developed material culture.

Otherwise, the history of Nusa Tenggara has not been has not been carefully studied. It was the Portuguese that first made eastern Nusa Tenggara into a place of importance. Before their arrival in 1512, this place was an out of the way place and foreign people seldom made a visit. Portuguese also gave the names to Timor and Solor, and brought Christianity missionaries along with them. In 17th century, Dutch tried to take over but little was done to this area.

During 17th century, Dutch began to colonize this region. Many people these days still live like their ancestors, fishing or farming. This area began to gain popularity when Komodo Island and surroundings became famous.Today this area is known mainly for the tourist spots of and Komodo island.

The largest indigenous group in the region is the Sasak people, who predominantly inhabit the island of Lombok. On Sumbawa Island, the indigenous population is traditionally divided into two main groups: the Sumbawa (Samawa) people and the Bima. Over time, waves of migration from Bali, Makassar, Java, Kalimantan, other parts of Nusa Tenggara, Maluku, and East Nusa Tenggara have significantly reshaped the demographic landscape. As a result, many indigenous communities are now concentrated in interior areas, while coastal regions are more ethnically mixed.

Historically, the region came under the influence of the Majapahit Empire at its height in the fourteenth century. Majapahit forces extended their control over the kingdoms of both Lombok and Sumbawa, integrating them into the empire’s political and trade networks. The Negarakertagama, written by Mpu Prapanca in 1365, records several place names in the region, referring to West Lombok as Lombok Mirah and East Lombok as Sasak Adi, and listing territories such as Taliwang, Dompo (Dompu), Sape, Sanghyang Api, Bhima (Bima), Seram (Seran), and Hutan Kedali (Utan). On Lombok island, the Sasak kingdom dominated this area until Balinese and Makasarrese attacked it. In the middle of 18th century, Balinese kingdom reigned over the island. Dutch occupied Lombok in the 19th century. After Indonesian independence, Lombok was dominated by Sasak elite, most are Muslim, and Balinese, most of whom are Hindus.

Buddhism and Hinduism never took hold in eastern islands such as Sumba, Timor, and Flores like they did in Bali and Java. Islam spread through traders in port towns, where it remained a religious enclave. However, these islands had developed strong animistic cultures separate from mainstream world religions and felt little need to change. In fact, outside religions posed a serious threat to their locally based power structures. The eastern islands were characterized by house societies, with ancestral homes serving as the cosmological centers of people’s notions of the universe. Such systems still exist to some extent in this region, which differs significantly from western Indonesia. The eastern islands had long developed headhunting societies that were in frequent warfare with one another. Headhunting was part of a cosmological belief system related to power and fertility, as well as a rite of passage to manhood.

East Nusa Tenggara has a strong missionary legacy, reflected in its religious composition. It is one of only two provinces in Indonesia—alongside South Papua—where Christianity is the predominant religion, with Roman Catholicism forming the majority faith. At the same time, Islam and indigenous belief systems, such as Marapu, continue to be practiced by segments of the population. The province’s marine environment is exceptionally rich in biodiversity, making it a popular destination for snorkeling and diving enthusiasts.

Tourism, Travel and Food in Nusa Tenggara

Tourism is a major part of the West Nusa Tenggara economy, especially in Lombok and the nearby Gili Islands (Gili Trawangan, Gili Meno, and Gili Air).The tourism sector in East Nusa Tenggara has experienced rapid development in recent years, especially due to the growing popularity of destinations such as Labuan Bajo and Komodo National Park, which draw visitors from inside and outside the country. Tourism Offices: A) Jl. Singosari 2, Mataram 83127, Tel. (62-370) 631730, 633886, 6358474, 6387828-9, fax: (62-370) 637233, 635274, Website: http://entebe.com, E mail: disbudpar@wasantara.net.id; B) Jl. Raya El Tari 2 No. 2 Kupang 85118 Tel. (62-380) 833104, 833650 Fax. (0380) 821540, goseentt.com

For those who prefer rugged terrain, exotic cultures and places that offers adventure, Nusa tengarra might be the place for you.Travel in the region is much easier than it used be. There are numerous flights to many cities; the ferries are frequent and regular; and the roads and bus links are good. You can visit Nusa Tenggara by air. From Darwin, Australia, you can go to Kupang twice a week, joinly operated by Air North and Merpati Nusantara Airlines. Silk Air operates from Singapore and Merpati offers flights from Kuala Lumpur to Mataram. Regular shuttle flights from Bali, Makassar and Surabaya provide excellent transportation links. You can also visit Bali first, from this island it's easier to reach Nusa Tenggara. What about traveling by sea? Awu, Dobonsolo, Dorolonda, Kelimutu, Sirimau, Tatamailau, Pangrango and Tilongkabila ferries serve Nusa Tenggara. Slow ferries also connect the small islands. There are PELNI ships calling at Nusa Tenggra Timur that regularly sail from Jakarta, Surabaya, Denpasar, Makassar, Biak etc.

Food: Sea food is naturally one of the specialties here. Freshwater fish is considered a delicacy and you might want to try gurami asam manis (sour and sweet fish known in the Latin name as Osporonemus gouramy). Sasak cuisine is considered quite spicy so you might want to ask before ordering dishes, if you prefer bland food. Sauteed vegetables are also popular here. Try pelecing kangkung, this sauteed green, leafy vegetable is tasty to be eaten hot with steamed rice. Ayam taliwang (roasted chicken with special sauce made of shallot, garlic, fish paste etc.) is a must, eaten with steamed rice and plecing kangkung (boiled greens, bean sprouts, peanuts coated with chili sauce) and sambal beberuk. They are very spicy though, especially sambal beberuk, made with lots of chili, tomatoes and eggplants.. Western style food can be found in many places.

Traditional Dwellings in Nusa Tenggara

Traditional houses in Nusa Tenggara in are highly diverse and reflect the distinct cultural identities of the region’s many ethnic groups. These houses are not merely shelters but powerful symbols of social order, cosmology, and communal values. Iconic forms include the cone-shaped Mbaru Niang of the Manggarai in Flores, the round Ume Kbubu of Timor used for storage and ritual activities, the towering stilted Uma Mbatangu of Sumba that signify status and ancestral connection, and the rectangular Musalaki houses of the Ende Lio, which function as the residences of customary leaders. Built primarily from local materials such as wood, bamboo, and thatch, these structures embody deep philosophical concepts concerning the cosmos, community, and the relationship between humans and their ancestors.

Key Traditional Houses:

Mbaru Niang (Manggarai, Flores): Tall, conical, multi-level houses that dominate the village skyline, symbolizing communal unity and the structure of the universe.

Ume Kbubu (Timor): Round, low-doored houses with thick thatched roofs, used mainly for storing corn and for women’s domestic and ritual activities, associated with fertility and respect.

Musalaki (Ende Lio, Flores): Large rectangular houses reserved for customary leaders, serving as centers of ritual authority, governance, and communal decision-making.

Uma Mbatangu (Sumba): Elevated tower houses with strikingly tall roofs, expressing social status and facilitating spiritual connections with ancestors.

Lopo (Timor): Circular, open-sided structures with conical roofs, used for communal gatherings, rest, and storage.

Ngada Traditional Houses (Flores): Wooden stilt houses divided into three main sections, each designated for different household functions, ranging from everyday activities to ritual observances.

These traditional dwellings share several defining characteristics. They are constructed almost entirely from natural, locally sourced materials such as wood, bamboo, and lontar palm leaves. Their architectural layouts often reflect cosmological principles, including the balance between the macrocosm and microcosm, gender symbolism, and reverence for ancestors. Functionally, the houses are well adapted to tropical conditions, providing ventilation, insulation, and designated spaces for culturally specific practices such as food preservation, ritual ceremonies, and community meetings. Although modern materials and designs are increasingly adopted for reasons of health and convenience, traditional houses remain central to cultural identity and continue to serve as enduring symbols of heritage in Nusa Tenggara.

Spirituality of Traditional Dwellings in Nusa Tenggara

Jill Forshee wrote in “Culture and Customs of Indonesia”: Across Indonesia, especially the eastern islands, homes define the center of people’s moral universes and identities. These regions fall under a type of social system described as a “house society.” Such homes link directly to the inhabitants’ ancestors and enclose their own sanctity, revered as places that ensure the safety, stability, and health of a family or clan. Sacred wooden posts (each of cosmological significance) support these homes and sections of the buildings symbolize male, female, public, private, forbidden, and sacred spaces. As noted, “Ethnographies of South-East Asian societies … provide evidence that ritual functions are inseparable from the house’s identity. What are sometimes referred to in older literature as ‘temples’ were, in fact, simultaneously inhabited houses of a kin group.” In house societies one’s home is indeed one’s temple. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Following this: An apparently universal rule in South-East Asian societies is that house posts always be “planted” (literally the term used in most instances) with their root or base end down, the same way as the tree originally grew. Symbolism of “base” and “tip” is highly elaborated in some Indonesian societies, and rules may even apply to the placing of horizontal members.Torajan people of Sulawesi consider the southernmost room of their homes as its root and a place to store their heirlooms. The Nuaulu people of the eastern Indonesian island of Seram plant their house posts along with sacred shrubs “always according to their natural orientation, that is, root end first … the house is thus considered to be, in a very real sense, ‘living.’ This aliveness is often expressed in anthropomorphic terms.” On the eastern Indonesian island of Buru, people express ideas about origin and cause based on imagery of living plants or trees. Roots and trunks of trees and the young leaves at the tips of branches form culturally significant reference points for these metaphors. Throughout Indonesians societies, this idiom of life parallels dualisms of near and far, sacred and profane, and ancestors and descendants, and defines various parts of a home.

Grass “Beehive” Homes of Timor, Flores, and Savu

Jill Forshee wrote in “Culture and Customs of Indonesia”: In contrast to elaborate homes, some abodes in regions of Timor, Flores, and Savu are basically windowless, grass roofs extending below the floor platform to the ground, with virtually no other visible materials or design. These houses resemble beehives, are extremely dark within, typically smoky, and residents regard them as womb-like enclosures for living in safety and privacy. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Such homes bear sanctified posts, altars, and heirlooms representing and honoring ancestors. In their interior obscurity, they appear unwelcoming and indiscernible to outsiders, but familiar to those within. In the centers of these dim, conical structures, women conventionally tend to forever burning fires, as pivotal and stable household presences—as within some traditional homes of Atoni or Tetun peoples of Timor Island. Platforms of varying sizes, heights, and significance either form seats for men or bear heirlooms and altars.

Houses of eastern Indonesia adhere closely to principles of dualism—forming opposing, paired concepts signifying cosmological thought and symbolism of local belief systems. The most predominant and recurrent dualism is male/female. While organizing much of life, this paired opposition also maintains a mystery and tension between its differences. Among the Atoni people of western Timor, house centers or entire interiors are symbolically female, whereas exteriors represent males. Women, however, may not sit upon male platforms within the house. As elsewhere, roof peaks or attics hold sanctity, where agricultural altars reside with heirlooms. The Wehali people of central Timor divide their homes into male and female spaces—both in terms of inside and outside, and with posts marking boundaries between the realms of men and women within a house.

Nautical and Shifting House Society of Savu

Jill Forshee wrote in “Culture and Customs of Indonesia”: “On the small island of Savu, between Timor and Sumba in eastern Indonesia, houses consist of three platform levels, as is common elsewhere. They also divide into parts named after those of living beings, such as a head, neck, cheeks, a space for breathing, a chest and ribs, and a tail (implying beings may always not be human). Like other Indonesian houses, those in Savu possess spiritual force. Although most people of the island are Protestant converts, a Savu home (amu) is bestowed with hemanga (semangat in Indonesian, signifying life force and spirit) through a series of ceremonies during its construction. After these are complete, people regard the house as a living entity, comparable to people, animals, or plants. A family house grows and multiplies through its descendents.50 Homes contain, foster, and emanate life. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

People of Savu also liken their island to a living being, with its “head” to the west and its “tail” to the east. The geography of the island thus divides into sections analogous to physical anatomy.51 The symbolism of the boat (perahu) also applies to Savu house layout. Customary homes follow the shape of a bow and a stern and are called by these terms. Thus, “like the members of a village, the members of a house form a group of passengers on a perahu.”52 Savunese historically have believed that their ancestors arrived from the west and that after death they will journey in that direction by boat to the next world. People orient the heads of deceased people and even sacrificed animals to the west—the direction of both origins and ultimate endings. Savu houses also follow a “base” and “tip” orientation, as in neighboring islands. The nautically symbolic “bow” of a house form is also its “base,” associated with men—whose patrilineage descends from its founder. The “stern” is like a “tip,” and relates to women, who move to their husbands clan homes from elsewhere after marriage.

Savu houses divide into male and female sections, reflecting a basic principle in eastern Indonesia. Household members all follow the founder’s patrilineage, and any may enter the male half of a home. Relatively open and “1light, this section offers a place for entertaining visitors. The female household portion, however, is not visible from the male section and is dimmer inside. Customarily, ceremonies held in its especially dark loft (storing food and weaving yarn) remain exclusively and secretively female. All house posts fall under male and female classification, following their position. Many Savu homes now follow the Indonesian modern, tract-like style. As long-standing Protestant converts, many Savunese have abandoned or neglected their former house forms and related cosmology to a good extent. Still, ideas integral to time-honored houses might apply in various degrees and manners to these contemporary residences, as clan identities go on.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Indonesia Tourism website ( ndonesia.travel ), Indonesia government websites, UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Japan News, Yomiuri Shimbun, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025