ATONI

The Atoni live in the central mountainous part of western Timor and East Timorese (former Portuguese) enclave of Oe-cussi, . Also known as the Atoin Pah Meto, Atoin Meto, Timorese, Orange Timor Asli (in Indonesian), they are largest ethic group in western Timor. Atoni means “man person’ and is short for “Atoin Pah Meto. Europeans called them Timorese. They number around 840,000, with 761,000 in West Timor and 80,000 in East Timor. Indonesians from Kupang may refer to the Atoni as "Orang Timor Asli" (native Timorese) in part to distinguish them with immigrant Rotinese, Savunese, and other settlers from nearby islands around Kupang. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~, Wikipedia]

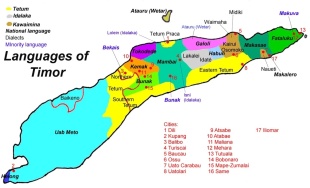

The Atoni in the central, mountainous region of Western Timor are bordered to the east by the Tetum people and to the west by the sea, as well as by the Rote people and other immigrant lowland groups around Kupang Bay and Kupang City, the capital of the province of East Nusa Tenggara which includes Timor. The Atoni are found between approximately 9°00' and 10°15' S and 123°30' and 124°30' E, in the mountainous central regions, and rarely by the malarial coasts with their poor soils. They wholly occupy the two administrative districts of North-Central Timor and South-Central Timor, part of Kupang District, and the former Portuguese enclave of Oecussi in West Timor. Indonesia has claimed and occupied Oecussi since 1975, though this has not been recognized by the United Nations.

Timor has been inhabited for thousands of years and has certainly received migrants throughout its history, yet the origin of the Atoni people remains unknown. Since the arrival of Portuguese and Dutch observers in the seventeenth century, they have been distinguished linguistically from their neighbors. The Atoni have probably been involved in the sandalwood trade for the past one or two millennia, mediated by Malays, Makassarese, and, later, Europeans. They were raided for slaves by outsiders. Though relatively isolated in their mountain homes, the Atoni developed princedoms before European contact in the late sixteenth century. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Timor was contested between the Dutch and the Portuguese, who ultimately divided the island, taking the west and east, respectively. However, the Dutch remained in Kupang, and the Atoni interior only came under direct Netherlands Indies government administration after 1912.

Language of the Atoni is Uab Meto, an Austronesian language in the Timor Group that is not mutually intelligible with languages of their neighbors on the island or nearby islands. . It had no written form until a Dutch linguist romanticized the script before World War II. Bahasa Indonesian, the Indonesian national language, is now used in offices, businesses, schools, the media, and some churches, A related dialect, Kupang Malay, was used by traders for centuries.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TIMOR factsanddetails.com

ATONI PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

KÉDANG PEOPLE OF EASTERN INDONESIA: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

ROTENESE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

NUSA TENGGARA factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

Atoni Religion

Christianity is the predominant religion. Some are Muslims. Folk beliefs are still alive. According to the Christian group Joshua Project about 95 percent of Atoni are Christians and 15 percent are Evangelicals. Christianity — mainly Catholicism in North-Central Timor and Protestantism in South-Central Timor and Kupang Districts — spread rapidly during the 1970s and 1980s.

Traditional Atoni religion revolved around beliefs in ancestral rewards and punishments. Deities and spirits included Lords of the Sky and Warth, ghosts and spirits of places and things. The Atoni belief in the power of spirits and ancestors and their ability to meet out justice remains. Traditional life-cycle rituals have been incorporated into Christian rituals. Traditional healers are called upon to deal with sorcery, curses and illness and to communicate with spirits and the Lords of the Sky and Earth. ~

Funerals are intended to make sure the spirit of the deceased and those of his or her ancestors don’t wander the earth bothering the living. Lineage alliances play a major role in the funerals. Processions to the burial grounds have traditionally been led by the wife-giving relatives of the deceased. They also carry the front part of the coffin. There is also a fair degree of present exchanging and other rituals involved with lineage alliances. Many of the rituals and liturgies are Christian. ~

Atoni Families and Marriage

Nuclear families among the Atoni form the basic household unit and is sometimes augmented by “borrowed children” from other families or widows or widowers. Widowed or divorced people often live alone or with a child or grandchild in separate domestic units usually close by. Mothers and the mother’s brother (the primary wife giver) are involved in raising children. [Source: Clark E. Cunningham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Among the Atoni marriage is equated with the attainment of adulthood and is viewed as a means of forming alliances between local lineages. Marriages have traditionally been arranged to continues old alliances or establish a new alliance and revolved around wife taking and wife giving that ideally worked out on an equal basis. A bride price is paid over time from the groom’s family to the bride’s family. The terms of the agreement are based on wealth and status and vary widely from region to region and even family to family. Atoni newlyweds usually live with the groom’s parents family although they may reside for a while with the bride’s family. Divorce is not all that common and often entails the repayment of the bride price.

Atoni men and women have traditionally done planting, harvesting and other agricultural chores together. They can both be seen in markets selling a variety of goods. Men usually do the heavy and dangerous work such tending cattle, hunting and repairing fences. Women tend small animals, gather plants and take care of children. Atoni children have traditionally been socialized through verbal and public affection by both parents. Corporal punishment is regarded as an acceptable punishment of children by parents, older children and of women by men. Children are taught to have respect for elders. Initiation rites and, among boys, warfare, were regarded as part of the growing up process but that is no longer the case. ~

Atoni Society

Traditionally the Atoni have been divided into three classes: aristocrats, commoners and slaves. Political organization was formed around princedom and kingdoms. Slavery was abolished by the Dutch and the princedoms remained powerful until they were eliminated by the Indonesian government in the 1970s. Society is now organized among more egalitarian lines. Headmen are elected. Many villages have two headmen: one who serves as a liaison with the national government and another who presides over local legal and customary matters. Clan elders sometimes take on leadership responsibilities. [Source: Clark E. Cunningham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Atoni society revolves around clan membership and lineage alliances. Atoni groups are organized along patrilineal descent lines, which may be large in size and widely distributed over a large area. The basic clan units are localized lineages of a name group. Sometimes several of these groups will cooperate in marriages and rituals and economic activities. Among the Atoni great importance is placed on lineage alliances based on wife giver and wife taker relationships among families over several generations. Goods are exchanged between alliance partners during life cycle events such as marriages, births and funerals. Property deemed to belong to a lineage is normally inherited by sons while property obtained through marriage can be inherited by the spouse and/or male and female children. ~

Many Atoni leaders still have noble blood and leadership positions are passed down along patrilineal lines. Church functions as a social organization but is not that involved in political and community activities. Among the Atoni birth is natural and assisted by knowledgeable women rather than specialists. Conflicts arise over inheritance, marriage and possession of orchards and animals. In most cases the matters are worked out on the villages level with the oversight of headmen and village elders. The settlements often involve the payment of fines. Moral transgressions are often believed to be settled by the spirits and God. ~

Atoni Villages and Homes

The Atoni have traditionally lived small dispersed settlements with 40 to 60 people in 20 to 40 houses set up in mountainous areas or along roads. Most settlements do not have a central common area or plaza or any public buildings. Some have modest wooden churches. Each village is surrounded with stone fence or shrubs, with fields and cattle cages on the periphery. The houses usually form a circular cluster, or follow a road. Traditional Atoni homes have a beehive shape, with the roof nearly touching the ground and are made of forest products. Many now live in rectangular houses made from wood or concrete, with windows. They are particularly numerous near roads and markets. [Source: Clark E. Cunningham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

According to ethnographer Clarke Cunningham, Atoni culture is notable for its spatial symbolism associated with a gender dichotomy. The male-female principle is important, as are the dualities of sun-earth, light-dark, open-close, dry season-wet season, outer-inner, central-periphery, secular-sacred, and right-left. These principles affect the spatial configuration of an Atoni house. The right side of the house (facing the door) is male, while the left side is female. The center of the house (and the attic) is male, while the periphery is female. The interior of the house is female and the terrace is male. The house is female, and the yard is male. According to this principle, the Atoni house is a microcosmos. The house also expresses social order. [Source: Wikipedia +]

A more elaborate house is called Ume Atoni, where "Atoni" means "male." The house is predominantly male. The Atoni entertain their guests in a communal house called a Lopo. A lopo is always located in front of a house and oriented toward the road. Furthermore, each cardinal direction is associated with a gender, as are different parts of a house. However, sex and gender do not always align. For example, an important lord is called a "female-man" and is always male but performs stereotypically female duties. +

Atoni Life, Culture and Economic Activity

The Atoni are primarily slash and burn agriculturalist who grow maize rice, raise chickens, pigs and cattle and collect forest products such as palm sugar and honey. The nuclear family is the primary farming unit, working its own plot with some help from other relatives. The rights to Atoni slash-and burn agricultural land has traditionally been controlled by clans and territorial groups. Orchards are held by families. As a rule land has traditionally not been treated as commodity. [Source: Clark E. Cunningham, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Valued property among the Atoni includes orchards, livestock, money, gold and silver jewelry and family heirlooms. The Atoni have traditionally made fine woven cloth, baskets and ropes but didn’t work metal and thus imported tools that they needed and the gold and silver jewelry they prized. Woodworking was once an important skill but is no longer widely practiced.

Dances and gong-and-drum music associated with traditional religious rituals have declined due to the advance of Christianity and the reduction in patronage from princes. The same is true for the formalized and poetic speaking ritual, which was important to nobles. There are few material arts other than the fine tie-dye weaving done by women and the ornamental basketry made by both sexes. ~

Illness may have natural or supernatural causes. Herbal medicines for the former are widely known. Some Atoni have remedies for the latter, but there are recognized specialists (mnane or meo) who deal with the supernatural. Childbirth is natural and is assisted by knowledgeable women, not specialists. Biomedical facilities are limited to some towns and rural health posts and are thus not easily accessible to most Atoni. ~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026