ROTENESE

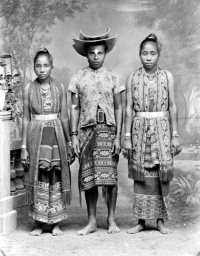

The Rotenese mainly live on Rote, off southwestern Timor, the southernmost Indonesian island, and in western Timor. Also known as the Atahori Rote and Hataholi Lote and sometimes spelled Rotinese, they tend to be short and light in build, with features typical of Malay populations, are and known for their characteristic sombrero-like hats and have a long traditional of education and working as civil servants. [Source: James J. Fox, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Rotenese derive their name from variants of their island’s name combined with a local word meaning “person” or “man,” such as Atahori Rote or Hataholi Lote. In ritual language, Rote is known as Lote do Kale, while “man” is expressed as Hataholi do Dae Hena. The Rotenese maintain that the name “Rote” is a Portuguese imposition. A seventeenth-century Dutch map, for example, labels the island Nusa Da Hena, meaning “Island of Man.” ~

According to the Christian group Joshua Project there were 27,000 Tii-speaking Rotenese and 40,000 Termanu-speaking Rotenese in the early 2020s. Census figures from 1980 record a population of just over 83,000 on Rote island. There were probably another 50,000 Rotenese on Timor and Semau at that time. Large numbers of Rotenese have migrated to the northeastern plains of Timor, as well as to Kupang and the island of Semau. In these areas, they have worked as rice cultivators, lontar palm tappers, traders, and, in Kupang, as civil servants. In addition to inhabiting Rote Island and western Timor, the Rotenese have also settled on surrounding islands, including Ndao (together with the Dhao), Nuse, Pamana, Doo, Heliana, Landu, Manuk, and several smaller islands. Rotenese communities are also found on Sumba and Flores. Owing to a long-standing emphasis on education, many educated Rotenese have settled in major cities throughout Indonesia.

According to tradition, the population is divided into two major territorial regions: Lamak-anan, encompassing the eastern half of the island and also known as “Sunrise,” and Henak-anan, covering the western half and referred to as “Sunset.” Although the former political significance of this division is unclear, it continues to mark differences in custom, dialect, and topography between east and west. Within these regions, Rote is further divided into eighteen autonomous domains, each ruled by its own lord. These domains constitute the largest indigenous political units and maintain distinctive styles of dress, speech, and customary law.

Language: The Rotenese language belongs to the Southwest Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family, and consists of several dialects, the main ones being Lole (Loleh), Ringgou, Termanu, Bilba, Dengka, Tii (Thie), Oenale, and Dela (Delha). According to Jonker, Rotenese shows the closest affinities with Belu (Tetum), Timorese (Atoni, Uab Meto), Galoli, and Kupangese languages. It shows more distant affinities with the languages of Kisar, Leti, Moa, and Roma. Each of Rote's eighteen domains has its own way of speaking, and Jonker distinguishes nine mutually intelligible dialects. One dialect, that of the central Termanu domain, has gained prominence as a lingua franca. Additionally, the Rotenese possess a form of ritual, poetic, or high language that crosses dialect boundaries. The small island of Ndao, with a population of approximately 3,500, is included within the political boundaries of Rote. Its population speaks a distinct language closely related to that of the island of Savu.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TIMOR factsanddetails.com

ATONI PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

KÉDANG PEOPLE OF EASTERN INDONESIA: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

NUSA TENGGARA factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

Rotenese History

The origin of the Rotenese is not clear. Some Rotenese traditions claim they migrated from the north in separate groups via Timor. They also have a tradition of accepting strangers from other islands as clients. Other traditions suggest that the Rotenese originally migrated from Seram Island in the Maluku Islands. Each domain has its own traditional narratives associated with its ruling dynasty. [Source: James J. Fox, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The first written references to Rotenese rulers suggests the Rotenese arrived on Rote Island during the Majapahit period (late 13th–16th century). Earlier, Rotenese groups established settlements on Timor, where they practiced slash-and-burn agriculture and used simple irrigation systems.

Headhunting appears to have been practiced in the past. There were means of settling disputes within lineages, clans, and at the lord's court. However, there was no traditional means of settling disputes between domains. In the past, such disputes often led to warfare. Since around 1850, however, domain warfare has given way to lesser feuding and border raids that persist to this day. Headhunting may have been ritually associated with agricultural fertility, but as an institution, it appears to have been eliminated or transformed by the eighteenth century.

Portuguese Dominicans established a mission on the island, then known as Savu Pequeño, in the late sixteenth century. However, by 1662, the Dutch East India Company had signed treaties with twelve domains in present-day Rote. These domains (nusak) were recognized as autonomous states until the twentieth century.

Until 1969, the Republic of Indonesia recognized eighteen domains, plus Ndao, within an administrative structure of four districts (kecamatan). Since then, this structure has been altered to six districts, each of which combines two or more former domains. An extensive school system in the nineteenth century gave the population an educational advantage in eastern Indonesia and stimulated emigration. Rotenese people now participate at all levels of Indonesian national life.

Rotenese Religion

Most Rotenese were Catholics but now the majority, some sources claim, are Protestants, with a significant community of Catholicism and a relatively small number of Muslims. According to the Christian group Joshua Project 80 percent of Tii-speaking and Termanu-speaking Rotenese are Christians, and five to 10 percent are Evangelicals. Traditional beliefs in ancestral spirits and their malevolent counterparts exists and you can still find representations of ancestors in some houses.

Christianity has been present on Rote since about 1600 and has long been associated with the spread of Malay literacy. In the early twentieth century, fewer than one-fifth of the population had been baptized, but widespread conversion followed national literacy campaigns and subsequent government certification of their success. Traditional Rotenese beliefs recognize a creator deity known as Lamatuan or Lamatuak, understood as the creator, predestinator, and source of blessing. This deity was symbolized by a three-branched pillar. Malevolent spirits are believed to inhabit the bush. Ancestral figures were represented by lontar-leaf effigies hung inside the house, which itself was regarded as a shrine to the ancestors. [Source: James J. Fox, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Ceremonies marked both major and minor transitions. Major ceremonies focused on marriage, house construction, and death. Minor rituals were held in the seventh month of a woman’s first pregnancy, at ritual hair cutting, baptism, naming, and whenever human blood was shed. Ceremonies were also linked to the agricultural and palm-tapping calendar, periods of illness, and recovery from sickness. Ancestral clans traditionally held an annual “feast of origin,” which marked the transition from one year to the next. This annual cycle, known as hus, has disappeared in most domains and survives only in Dengka. During the hus cycle, each clan possessing ceremonial rights performed prescribed rituals in a fixed sequence over several weeks, usually between August and October. These ceremonies included invocations of the ancestors and petitions for the fertility of animals and crops, along with horse racing, dancing, mock battles, and animal sacrifice. In most cycles, one clan was responsible for performing rain rituals on a hilltop.

There was no formal priestly class in traditional Rotenese religion. Instead, certain men were recognized as ritual chanters who recited long ceremonial poems during major feasts. Any adult man could make offerings to the spirits, while the mother’s brother held a central ritual role and was required to officiate at all life-cycle ceremonies for his sister’s children.

Funerals were the most elaborate of all Rotenese ceremonies. Funerals were marked by feasts held on the third, seventh, ninth, and fortieth days after death, and sometimes included dog sacrifice. The souls of those who died violently were believed to be separated from other ancestral spirits and to become malevolent beings wandering the earth. The deceased’s mother’s brother, or mother’s mother’s brother, prepared the coffin—known as the “ship of the dead”—and oversaw the digging of the grave. Burial usually took place on the third day after death, followed by additional commemorative feasts that might occur one or even three years later. There were no secondary burial rites involving exhumation. On the day following burial, the mother’s brother performed a purification rite to “cool” the close mourners and release them from their ritual fasting.

Rotenese Society, Kinship and Political Organization

Rotenese society was traditionally organized into territorial domains composed of several clans. Each domain was ruled by a complementary pair of male and female lords and their court, while the rest of the population was regarded as commoners. Core features of Rotenese social organization included nuclear-family households, large extended families of a generally patriarchal character, and the maintenance of clan exogamy, which required marriage outside one’s own clan and community. Extended family groupings were formed from smaller descent units known as nggi leo; these, in turn, combined to form larger clans called leo. In the past, warfare occurred between domains, and as late as the 1990s occasional cross-border raids were still reported. [Source: James J. Fox, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Each domain consisted of a number of named origin groups or clans (leo), which functioned as its primary political units. Clans were subdivided into named lineages (teik), which were further divided into smaller “birth groups” (bobongik), and finally into individual households (urna). While clans and lineages were not territorially fixed, birth groups tended to cluster within the same village areas. Descent is conventionally described as patrilineal, but in practice the continuity of origin groups was maintained through genitor lines traced via an inherited system of alternating personal names. These so-called “hard names,” regardless of whether they were inherited from the father or mother, were associated with the masculine aspect of the person, and origin groups were therefore conceived as symbolically male.

When bridewealth had been paid, children belonged to their father’s origin group and received part of his hard name; this was the most common form of lineage ascription on Rote. If bridewealth had not been paid, children necessarily belonged to their mother’s group and took part of her hard name. Although lineage affiliation was not exclusively lineal, it was not a matter of personal choice, and there was no optative element in Rotenese descent.

Rotenese kinship terminology was highly articulated. Fathers and fathers’ brothers were distinguished from mothers’ brothers, and mothers and mothers’ sisters were distinguished from fathers’ sisters. Same-sex siblings and parallel cousins were classified by relative age, while opposite-sex cross cousins were distinguished from parallel cousins. A particularly important kin relationship was that between a mother’s brother and his sister’s children, which was specifically marked in kinship terminology.

Politically, each domain was traditionally governed by a male lord (manek) and a complementary female lord (fettor), assisted by a group of court lords ideally selected from each clan within the domain. One court lord held the title Head of the Earth (dae langak), serving as the principal guardian of customary law and possessing, in certain circumstances, the authority to override the decisions of the lords. The clan of the Head of the Earth claimed settlement priority and ritual rights over the land.

Nobility was associated with the clans of the male and female lords, while all others were considered commoners. Although wealthy individuals were sometimes spoken of as forming a distinct social category, it was neither theoretically nor practically possible for a wealthy commoner to become a noble. A former slave class existed in the past but was eventually absorbed into other social categories. When the domain system was abolished in the 1970s, many of its functions—particularly the resolution of local disputes—were transferred to village-level administration. Despite these changes, Rote’s traditional clan structure has persisted in modified forms under modern institutions.

Rotenese Marriage and Family

Rotenese marriages are defined by 1) the amount of bride wealth given, 2) the amount of feasting that goes along with the wedding and 3) the length of the bride service performed. Bride-wealth is usually paid in gold, old silver coins, water buffalo, sheep or goats. Polygyny is practiced by the wealthy. Divorces are easy to obtain, traditionally, with permission obtained from the lord's court. [Source: James J. Fox, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Although lineages are exogamous, Rotenese clans are not. Marriage is prohibited between siblings and close parallel cousins. More distant parallel cousins, however, are potential marriage partners. While marriage is preferred, it is not prescribed, between cross cousins. The stated preference is for marriage with the mother's brother's daughter. In Thie and Loleh, a moiety system partially regulates marriage. Levirate, sororate, and adoption are extremely rare. ~

Eldest sons and daughters leave home upon marriage, while the youngest son remains with his parents. The youngest son inherits the paternal house and brings his wife to live there. All elder sons must establish a new residence before or shortly after marriage. This residence is usually in the same village area, but never too close to the paternal house. The domestic unit is based on the nuclear family and generally consists of a husband, wife, and unmarried children. The only exception is the youngest son and his wife. Widows can maintain their own households and raise their children independently. Regarding inheritance, the eldest son inherits the right to represent his father in marital ceremonies and receives all marital prestiges. The youngest son inherits the house. Other wealth is divided equally among all sons. A daughter (or daughters) may only inherit if there is no male heir.

Rotenese Life, Villages, Houses and Culture

The staple of the Rotenese diet is syrup tapped from the lontar palm. It is mixed with water for everyday consumption and also processed into thin cakes and fermented into a dark beer, which in turn may be distilled to a sweet gin. Maize, millet, sorghum and a variety of tubers, fruits and vegetables are eaten. People often eat, porridge and fish with spicy seasonings. Rice is regarded as a luxury. During feasts rice and millet are boiled meat. [Source: James J. Fox, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, Wikipedia]

The traditional Rotenese house is the focus of Rotenese life. It is divided into male and female halves and traditionally has had a thatched roof with gabled ends. The house is raised off the ground on posts that extend over a ground floor area with resting platforms, where guests are received. Because of a lack of wood on the island many of these have been replaced by cement or stone structures. ~

Traditionally, villages were fairly compact for defensive reasons. Traditions maintain that before the emergence of territorial domains, each clan or origin group, identified with a named ancestor, occupied its own territory near a defensible walled redoubt. Following the formation of the domains, these clans were assigned specific roles in defending the fortified centers of their lords. After the establishment of peace under Dutch colonial rule, settlement patterns changed and became more dispersed. For administrative purposes, the Dutch attempted to define villages or village areas—today often marked by a church or local school—but in practice houses continued to be scattered individually or in small clusters wherever reliable sources of fresh water were available for drinking and gardening.

The Rotenese have preserved a rich oral literature and are renowned for producing finely woven tie-and-dye textiles. Both oral tradition and textile production were formerly integral components of ritual life. Traditional Rotenese attire consists of a kain—a cloth up to about 2.5 meters in length, wrapped around the waist and worn to the knees or ankles—together with jackets or shirts and a distinctive straw hat known as ti’i langga. The typical household is relatively small and based on patrilocal residence, with the wife settling in her husband’s community after marriage. [Source: Wikipedia]

The number of indigenous healers who once practiced curing with a variety of specialized and often secret medicines has declined. In the past, serious illness was addressed through small ritual feasts involving offerings to the spirits. In contemporary practice, such gatherings are more likely to involve Christian prayer for the sick.

Rotenese Agriculture, Work and Economic Activity

The livelihood of the Rotenese people traditionally combined agriculture, animal husbandry, fishing, tapping neera from palms, and a range of household crafts. Well-irrigated land was used for wet-rice cultivation or as water-catchment areas. Livestock raising focused on water buffalo, cattle, horses, and poultry. Women played a central role in producing traditional handicrafts, including woven textiles, pandan-leaf plaiting, pottery, and other domestic goods, while small-scale trading was common. [Source: James J. Fox, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, Wikipedia]

A large share of Rotenese subsistence was derived from tapping the lontar palm (Borassus flabellifer) and reducing its sap to syrup. Mixed with water, this syrup formed the daily staple. Maize, millet, sorghum, tubers, beans, mung beans, peanuts, squash, sesame, onions, garlic, and various cucurbits were widely grown in dry fields and household gardens enriched with animal manure. Common fruit trees included banana, papaya, breadfruit, jackfruit, citrus, mango, and coconut. Tobacco, cotton, betel (with a preference for the nut rather than the leaf), and areca were also cultivated.

Despite living in a dry region with an irregular monsoon, the Rotenese developed sophisticated wet-rice agriculture by diverting rivers and streams and using natural springs for irrigation. Although wet-rice plots were individually owned and cultivated, they were organized into cooperative irrigation units that maintained shared fencing and appointed members to manage water distribution. Dry fields were typically cleared by burning in November. Over the past century, wet rice and maize became dominant crops, though dry rice, millet, and sorghum continued to be grown. Wet-rice fields were prepared by driving herds of water buffalo through the softened soil, while dry fields were worked with steel digging sticks and hoes.

Fishing was a regular activity, particularly during the dry season. Offshore stone weirs trapped fish as the tide receded, and rivers yielded shrimp and eel. Women commonly fished with scoop nets, while men used spears or cast nets; basket traps, hook and line, and fish poison were employed less frequently. Hunting was limited to small birds, a few remaining deer, and the occasional feral pig. Honey, mushrooms, seaweed, and agar-agar were gathered to supplement the diet. The Rotenese kept herds of horses, water buffalo, sheep, and goats, and most households also maintained dogs, cats, pigs, and chickens.

Weaving—particularly the production of tie-and-dye cloths—and basketry were the principal domestic arts. Pottery, produced in only a few areas with suitable clay, was widely traded across the island. Itinerant Ndaonese goldsmiths periodically attached themselves to wealthy households, where they crafted gold and silver jewelry.

Trade was conducted both within Rote and with Kupang on the island of Timor, where exchange increasingly involved Chinese and Muslim traders. Livestock and foodstuffs were traded for items such as broadcloth, cotton thread, kerosene, tobacco, and areca nuts. Aside from pottery, occasional flintlock firearms, and betel, relatively little trade occurred between Rotenese communities themselves. Interisland trade with Kupang grew steadily in importance.

Clans held rights to water sources and appointed a ritual head to oversee the collective of landholders whose fields were irrigated by that water. Land, trees, and animals were owned by individual households. The principal forms of movable wealth included locally woven cloths, gold and silver ornaments, ancient mutisalah beads, and old weapons.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026