KÉDANG

The Kedang live on the island of Lembata, which is east of Flores and north of Timor. Also known as the Edang, they are primarily slash and burn farmers who do a small amount of coastal fishing and raise a few animals. Most are Roman Catholics. Some are Muslims. A few retain their traditional beliefs. Culturally and linguistically, the Kédang people are closely related to their western neighbors, the Lamaholot, with whom they share many aspects of social organization and religious belief. [Source: R. H. Barnes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

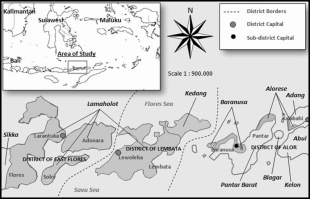

The Kedang region lies on the north coast of Lembata Island and covers about 266 square kilometers (103 square niles) including two administrative districts — Omesuri and Buyasuri. Lembat island lies between 8° 10 and 8°20 S and between 123°35 and 124° E, at the east end of the island of Lembata (known on most maps as Lomblen) in the Indonesian province of Nusa Tenggara Timur. ~

According to Joshua Project the Kedang population was 37,000 in the early 2020s. According to the 1980 Indonesian census there were 28,677 persons living in Kédang. At that time the average population density was 108 persons per square kilometer. There were 81 males per 100 females, compared with 99.6 for the province as a whole. This low figure results in part from out-migration of men seeking employment elsewhere. The ratio among the age group 15 to 24 years, for example, is 53 males per 100 females.

Little is known about Kédang history prior to the late 19th century. In the 1870s, the raja of the neighboring island of Adonara, with Dutch military support, established political control over Kédang. The Dutch themselves did not intervene directly until 1910, when they entered the area in force, disarmed the population, and carried out island-wide registration. From that point onward, Kédang history became closely integrated into that of the Dutch East Indies and, later, the Republic of Indonesia. Catholic missionaries began working in Kédang in the 1920s, although conversions to Islam occurred at a similar pace.

Language Kédang (Kdang, Dang, Kedangese), the language spoken in the Kedang region by the Kedang, is an Austronesian language in the Malayo-Polynesian sub-family. There are approximately 30,000 speakers of the language. The Kédang speak "the language of the mountain" (tutuq-nanang wéla), as opposed to coastal, lowland language of the Lamaholot. The Kegang language also show affinities with Bahasa Alor on the islands of Pantar and Alor to the east. Bahasa Alor is often regarded as a dialect of Lamaholot. In contrast, the Kédang are neither culturally nor linguistically related to the larger populations of Alor and Pantar who speak non-Austronesian languages.

RELATED ARTICLES:

LARANTUKA AND LAMALERA IN EAST FLORES: UNUSUAL FESTIVALS, WHALE AND MANTA RAY HUNTS factsanddetails.com

LAMAHOLOT PEOPLE OF FLORES: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

ALORESE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

ALOR ISLAND factsanddetails.com

FLORES: VOLCANOS, SIGHTS, LABUAN BAJO factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF FLORES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON FLORES factsanddetails.com

NUSA TENGGARA factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

Kédang Religion

According to the Joshua Project Christianity 48 percent of Kédang are Christian, with Evangelicals, making up two five percent of them. Census data show a shift in religious affiliation in Kédang over time. In 1970, local records indicate that 45 percent of the population was Muslim, 28 percent Catholic, and 27 percent continued to follow traditional religion. By 1980, official figures reported 52 percent Muslim and 48 percent Catholic, a distribution that obscured the number of people who had not fully converted to either faith. While these statistics do not reflect levels of personal religious commitment, the growth in Catholic affiliation between 1970 and 1980 mirrors broader regional trends. Despite formal religious identities, Muslims and Catholics often continue to participate in traditional rituals, and some villages have revived communal ceremonies that had previously declined due to religious divisions. Traditional belief centers on a deity associated with the moon and sun, known as Ula Loyo, without the inclusion of the earth as part of a unified divine concept, unlike neighboring Lamaholot beliefs. [Source: R. H. Barnes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The incorporation of traditional religion into Catholicism and Islam is reflected in the names for God: Moon-Sun, Great Sun, White Sun, Morning Star-Sun and Great Morning Star. Traditionally, the sun has been viewed as male and the Pleiades and the morning star are associated with divinity. In their belief system there are also guardian spirits, free spirits and witches. The sun and moon represent contrasting aspects of divinity. The sun is male, creative, and associated with constant, ordered change, while the moon has an indeterminate gender and, although considered mythically unproductive, is closely linked to the calendar, biological rhythms, and bodily processes.

Religious Specialists today increasingly include Muslim leaders (hajjis) and Catholic priests and nuns. In addition to Catholic and Muslim rituals, the Kedang also conduct special village purifying and agricultural ceremonies. Feasts are held at funerals and marriage presentations. On occasion rain-making ceremonies are held. In traditional practice, two types of ritual experts were distinguished: priests skilled in divination and the performance of communal and individual rites (molan-maran poan-kémir), and those specializing in healing and traditional medicine (molan-maran potaq-puiq).

Ceremonial Life encompasses Muslim and Catholic worship as well as indigenous rituals marking birth and death. Some villages have revived annual purification ceremonies held at the onset of the rainy season in December. In the past, large communal harvest ceremonies—especially connected with beans—were common during the dry season; today, similar rites are still conducted within descent groups. Rituals honoring personal guardian spirits are performed in times of misfortune, and rain-making ceremonies are occasionally held. Feasting commonly accompanies marriage exchanges and funerals.

Beliefs about Death and the afterlife distinguish between ordinary deaths and those that are sudden, violent, or otherwise abnormal. After death, the Kedang believe, people go through a process of death and rebirth through levels of the universe and are briefly a fish before ascending to their place with God. Only death at an advanced age is considered a “good” death. Those who die normal deaths continue through the remaining levels and, after their final death, their bodies are transformed into fish while their souls return to God. By contrast, individuals who suffer a “bad” death cease this cycle; their souls remain at the horizon and periodically return on the wind, bringing misfortune to the living.

Kédang Society and Political Organization

Kédang society is characterized by relatively fluid social distinctions and strong kinship-based organization. Clear class divisions are largely absent, although in the past Kédang may have been a source of slaves, a subject about which little detailed information survives. Until fairly recently, certain families in the village of Kalikur were regarded as a form of local nobility, exercising influence that set them apart from the rest of the population. [Source: R. H. Barnes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Villages and hamlets are composed of several named patrilineal clans. These clans are interconnected through networks of asymmetric marriage alliances that structure social relationships, obligations, and cooperation within and between communities.

Kinship terminology and social relations follow the principle of patrilineal descent. Marriage is ideally prescribed within the category known as mahan, which includes cross-cousins—specifically, a mother’s brother’s daughter and a father’s sister’s son. These marriage rules reinforce enduring ties between clans and help maintain the balance of alliance relationships.

Political organization at the village level has changed substantially over time. Under the modern Indonesian state, grassroots political activity in rural areas has largely been absorbed into formal political structures, particularly through the government-aligned organization GOLKAR. Historically, however, clans from the village of Kalikur at times held political and military dominance over other Kédang communities. This prominence was formally acknowledged during the Dutch colonial period through the appointment of a rian-barat (“great and heavy one”), a position comparable to that of a subraja.

Kédang Family and Marriage

Kédang households typically consist of a husband, wife, and their children, with membership expanding or contracting over time to include elderly parents, sons-in-law, and occasionally grandchildren. As in all communities, demographic circumstances shape the precise composition of each household. Inheritance follows the patrilineal line. Valuables, houses, and obligations arising from marriage alliances are passed down through male descendants, reinforcing the importance of patrilineal continuity in social and economic life. [Source: R. H. Barnes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Child-rearing is shared by parents and a wider circle of relatives, and physical punishment of children is rare. Following the birth of a child, parents observe a period of ritual restriction involving limitations on movement, the use of water, and hair cutting. Apart from Islamic and Catholic rites, there are no formal ceremonies marking stages of growth from the end of this restricted period until youth and early adulthood. At that stage, some individuals traditionally underwent tooth filing and blackening, although this practice is now disappearing. Age is closely associated with authority in Kédang society: elders command respect, supervise clan affairs, and play key roles in decision-making. Elders from the mother’s clan hold a particularly valued position, as they are believed to possess life-giving qualities and spiritual influence over their sister’s children.

Marriages involve an elaborate series of exchanges set by social class seen as alliance builders. In the old days there was no marriage ceremony and the series of exchanges could continue well beyond the lifetimes of the spouses. Marriages today are in line with the customs of the Catholic or Islamic faiths. Gifts traditionally included elephant tusks, gongs and fine ikat cloth. Divorce is common among non-Catholics.

Kédang society distinguishes clearly between wife-giving and wife-taking groups, with wife-givers regarded as socially superior. The mother’s close male relatives are believed to control the health and well-being of her children and are revered as quasi-divine figures. Polygyny is permitted among non-Catholics and occurs on a limited basis. Newly married couples are generally expected to live with the wife’s parents for several months to a year before establishing an independent household. When spouses come from different villages, they usually settle near the husband’s patrilineal kin, although many exceptions exist.

Kedang Villages. Life and Culture

The Kédang traditionally lived in bamboo houses supported on posts and roofed with grass or palm leaves, carefully oriented in accordance with indigenous religious beliefs and local concepts of space. These dwellings reflected both practical needs and cosmological principles embedded in everyday life. In recent decades, and with encouragement from the government and Catholic missions, increasing numbers of brick houses with corrugated iron roofs have been built.[Source: R. H. Barnes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Historically, Kédang settlements consisted of villages of a few hundred people, made up of several named hamlets. Under Indonesian government administration, many of these have been reorganized into larger “administrative” villages with populations of roughly 1,000 to 2,000 inhabitants, sometimes through the consolidation of two or more older settlements. Village governance now includes an elected head, treasurer, and secretary. During the wet monsoon, when agricultural labor is intensive, many villagers spend long periods living in field huts located several kilometers from their main villages.

Men typically fish, hunt, and conduct the lengthy negotiations involved in marriage arrangements and the exchange of marriage gifts; a small number of women also participate in hunting. Cooking, except during large ceremonial feasts, is mainly the responsibility of women and girls. Both men and women work together in clearing, planting, weeding, and harvesting fields.

While the Kédang are highly skilled in working bamboo and wood to produce houses, tools, and musical instruments, they are not known for visual arts such as painting, decorative carving, sculpture, or weaving. In the old days children had their teeth blackened and filed as part of coming of age rituals.Access to healthcare has improved with the establishment of government clinics. Otherwise care is in the hands of traditional healers. ~

Kédang Work and Economic Activity

Most Kédang households rely on subsistence swidden agriculture, Maize and dry rice form the core of the Kédang diet and are the primary staple crops. They are supplemented by tubers, vegetables, and spices. Copra, tamarind, and candlenuts are cultivated as cash crops, while many men seek additional income by working at small-scale mines or leaving the island to work elsewhere . Cotton is grown for local use, and palms are extensively exploited for food, construction materials, and other everyday needs.. Coastal fishing is practiced on a small scale. Domestic animals commonly include pigs, chickens, goats, and dogs. Schoolteachers and a small number of other workers earn regular wages. [Source: R. H. Barnes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Kédang women were traditionally forbidden to weave, although today many produce cloth for everyday use. Weaving, however, remains prohibited in ritually important ancient village centers. The Kédang proper historically lacked specialized crafts such as pottery, blacksmithing, and the weaving and dyeing of fine ikat textiles. These goods were instead supplied in limited quantities by residents of neighboring groups who lived among them.

Trade plays a modest but important role in the local economy. Some coastal communities engage in small-scale trading, and weekly markets provide opportunities to purchase basic goods and produce with cash. Increasing numbers of young men travel beyond Kédang in search of work, reaching destinations as distant as Malaysia. A small number of permanent shops, often operated by Chinese merchants, are found in the larger villages.

Land Tenure was traditionally based on collective village ownership, represented by descent groups regarded as the “lords of the land,” typically believed to be the earliest settlers. Other descent groups obtained rights to use land through permission from these founding groups. Individual usage rights were established by clearing and maintaining fields. Since the end of World War II, government policies have promoted the reopening of land previously rendered unsafe by warfare and piracy and have encouraged a gradual shift toward more individualized concepts of land ownership.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026