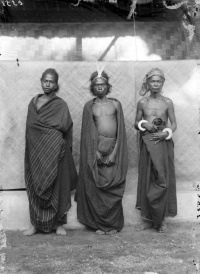

PEOPLE OF FLORES

Flores is a wonderful island (east of Komodo with friendly people who are noticeably blacker—more closely related to the people from Papua New Guinea—than the people on islands to the west. Flores is one of the poorest islands in Indonesia. It doesn’t have any natural resources. The prosperity of many farmers depends on prices of its main cash crops, cacao and cashews. Sukarno was exiled here and wrote movingly about the common values of Catholics and Muslims. On Flores some people still perform headhunting dances. High quality ikats are available.

Population of Flores was estimated to be 2,014,110 in mid 2024, which works out to a population density of 146.4 people per square kilometers (379.2 per square mile). The population of Flores in the 2010 census was 1,831,472. Although the large majority of inhabitants are indigenous Florenese, the total figure includes undetermined numbers of people belonging to several minorities, including Savunese, Buginese, Sama-Bajau, and Chinese.. [Source: Wikipedia]

Languages spoken on Flores belong to the Central Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. They are commonly divided into two major groupings. The first includes the Manggarai languages of western Flores and the Ngadha–Lio group spoken in the island’s central regions. The second consists of languages classified within the Flores–Lembata subgroup of the wider “Timor area” group, which are spoken primarily in eastern Flores.

RELATED ARTICLES:

HOMO FLORESIENSIS: HOBBITS OF INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

ORIGINS AND ANCESTORS OF HOMO FLORESIENSIS (HOBBITS) factsanddetails.com

FLORES: VOLCANOS, SIGHTS, LABUAN BAJO factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON FLORES factsanddetails.com

WESTERN FLORES: ISLANDS, TRADITIONAL VILLAGES AND HOMO FLORESIERNSIS (HOBBITS) factsanddetails.com

SIKKA PEOPLE OF FLORES: RELIGION, CULTURE, LIFE, SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

MANGGARAI PEOPLE OF FLORES: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL-EASTERN FLORES; ENDE, KELIMUTU. MAUMERE factsanddetails.com

ENDE PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

LARANTUKA AND LAMALERA IN EAST FLORES: UNUSUAL FESTIVALS, WHALE AND MANTA RAY HUNTS factsanddetails.com

LAMAHOLOT PEOPLE OF FLORES: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

ALORESE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

ALOR ISLAND factsanddetails.com

NUSA TENGGARA factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

History of Flores

Flores gained worldwide attention with the 2004 discovery of Homo floresiensis, an extinct, tiny human species nicknamed the "Hobbit" due to its small stature (about 3 feet tall) and brain size and relatively large feet. It lived on Flores until as recently as 50,000 years ago. Archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest presence of Homo sapiens on Flores dates to approximately 11,000 years ago, significantly later than on nearby large islands such as Timor. Austronesian-speaking populations are believed to have arrived on Flores around 4,000 years ago. Several ethnic groups—including those in Manggarai (western Flores), Nage, Keo, and Ende (central Flores), and Lio (eastern central Flores)—maintain oral traditions tracing their origins to Sumatra or Java. [Source: Gregory Forth, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Prior to European contact, Flores functioned as an important stopover in regional trade networks. Javanese traders, in particular, used the island as a port of call, especially in the sandalwood trade linked to Timor. In the early sixteenth century, the Portuguese established a foothold in eastern Flores, notably in Larantuka, and in south-central Flores on the island of Ende, where they constructed forts and founded Catholic missions. During this period and into the following century, Portuguese influence competed with expanding Muslim networks originating largely from South Sulawesi. At the easternmost tip of Flores, Larantuka is famous for its Easter-week rituals that still continue the old Portuguese traditions brought here some 500 years ago.

The seventeenth century witnessed the emergence of local polities shaped by these external influences. In southeastern Flores, the Sikka region saw the formation of a rajadom led by a Portuguese-supported Catholic ruler, while further west in the Ende region, an Islamic rajadom developed around the same time. Over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Portuguese dominance gradually gave way to Dutch control as the Netherlands became the primary European power in the region.

During the eighteenth century, coastal areas of Manggarai came under the influence of the Bimanese from Sumbawa, located east of Flores. Although Bimanese power declined following the catastrophic eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815, it was reasserted in 1851 before finally ending with full Dutch consolidation of authority in 1929. The Dutch formalized relations with local rulers, including a contract signed with the raja of Ende in 1839, but effective administrative control over much of Flores was not achieved until after a military campaign launched in 1907. Dutch rule continued until the Japanese invasion in 1942.

Following World War II, Flores became part of the Dutch-established State of East Indonesia, which was dissolved in 1950, after which Flores was incorporated into the Republic of Indonesia. Despite earlier Portuguese presence, widespread Catholic missionary activity across Flores did not begin until the early twentieth century, contributing to the island’s present-day religious landscape.

Religion on Flores

Flores is home to the greatest concentration of Catholics in Indonesia. There are about 1.2 million of them. Catholicism arrived on Flores in earnest in 1914, when priests from the German-based Society of the Divine Word systematically moved from the coasts to the mountains and had great success converting almost everyone to Catholicism. An earlier effort by Jesuits largely failed. Pope Paul VI visited in 1967. Pope John Paul II came in 1989 and conducted mass in Maumere stadium. Local priests and nuns are very involved in running the island’s affairs. The religious make up of Flores are Roman Catholic (83.6 percent); Protestantism (1.17 percent); Islam (15.2 percent); Hinduism (0.05 percent) and Buddhism (0.01 percent).

All ethno-linguistic groups on Flores acknowledge a distant and largely inactive creator deity. In several traditions, this divinity incorporates complementary male and female aspects. Among the Sikka, for instance, Lero Wulang—literally “Sun and Moon”—is paired with the feminine Nian Tana, whose name refers to the surface of the earth. Despite recognition of such a supreme being, ritual attention is generally directed more toward ancestors and a range of autonomous spirits. The spirit category nitu (comparable to the Manggarai darat) is recognized throughout central and eastern Flores and refers to forest or “nature” spirits as well as spirits of the dead. In Manggarai, Nage, and Sikka, beings known as naga are identified as guardians of houses, settlements, and the land itself. Belief in witches—individuals believed to possess a malevolent spiritual force absent in morally normal humans and capable of causing illness or death—is widespread across the island. These indigenous beliefs and ritual practices have persisted despite the fact that, by the latter half of the twentieth century, most Florenese had converted to Catholicism or Islam. [Source: Gregory Forth, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Religious Practitioners include individuals skilled in specialized ritual languages, enabling them to communicate with ancestors and other spiritual beings, as well as witch-finders, magicians, and other ritual specialists. Such roles are usually attained through personal aptitude and inclination, and it is common for a single individual to perform multiple ritual functions. Practitioners are predominantly male, although the degree of women’s participation in religious and magical activities varies by ethnic group and is, in some cases, substantial. In the matrilineal society of Tana ‘Ai, men exercise authority in ceremonial matters, while women hold leadership roles in the secular affairs of descent groups. In many regions, a male “lord of the land,” typically drawn from the group with the longest-established territorial claims, serves as the principal authority in ritual and spiritual matters related to land and agriculture.

Ceremonial Events include harvest festivals and annual hunting rituals. In central Flores, collective water buffalo sacrifices—performed by a single village at intervals of several years or even decades—are common. Among the Nage and Keo, such sacrifices play a crucial role in publicly asserting and reaffirming, and at times renegotiating, rights to land and group membership. Funerals, particularly those of high-ranking individuals, along with other life-cycle rituals such as initiations and marriages, can be highly elaborate and entail substantial expenditures, especially in the form of sacrificial animals.

Medicine and Funerals on Flores

On Flores, cures combine the administration of physical medicines, mostly from plants, with massage and bodily manipulation, along with rituals incorporating offerings to spiritual entities. Modern medicines and treatments from clinics and hospitals became widely available in the late twentieth century and are often used alongside indigenous healing practices. [Source: Gregory Forth, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Illness is usually regarded as having spiritual causes, such as mystical attacks by witches or sorcery. Medical practice is generally a status achieved through training. Throughout Flores, people recognize powers called ru'u (or uru), which are invoked to protect fruit-bearing trees or crops. This term refers to physical signs of prohibition, punitive power, and kinds of illnesses or conditions that manifest this power. These illnesses are believed to result from breaches of the prohibition, and they can be cured by human owners of this power.

Death, like illness, is commonly attributed to spiritual malevolence, the violation of a taboo, or the failure to fulfill customary obligations. Burial is the usual method of disposal, though in the Ende and Lio regions secondary mortuary treatment was formerly practiced for individuals of high status. Funerary rites typically involve animal sacrifice and, in some areas, prestations to the deceased’s affinal relatives, though the scale and duration of these rituals vary widely. Special rites are required for those who die violently or experience a “bad” death. Most ethno-linguistic groups conceive of a land of the dead or afterworld, often associated with an uninhabited or remote location such as a mountain peak. Variants of a myth explaining the origin of death are found throughout Flores, commonly involving a contest between two birds.

Family and Marriage on Flores

Households are typically made up of a single extended family, at least during certain phases of the domestic cycle. Prior to the early twentieth century, however, much larger residential groups were common; in Manggarai, for example, as many as two hundred people could share a single dwelling. In Sikka, “royal houses” accommodating up to fifty residents have been recorded. In earlier periods, households could also include slaves in addition to kin. [Source: Gregory Forth, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

The care of young children is primarily the responsibility of mothers, other adult women, and elder sisters, though fathers and male siblings also contribute to child-rearing. In some regions, fosterage by members of the parents’ kin groups is a regular practice. The transition to adulthood is traditionally marked by initiation rites, including circumcision for boys and teeth-filing for girls. Today, most children attend at least primary school, either in state or Catholic institutions. Across most, if not all, regions, children are treated with considerable indulgence and are rarely subjected to physical punishment.

Marriage Practices vary, but among the Nage and Keo there exists a distinctive institution of temporary sexual unions that are formally differentiated from marriage yet require a payment similar to bridewealth. A related practice involving the exchange of gifts for women’s sexual favors has also been reported among the Endenese.

When bridewealth is fully paid, postmarital residence is typically patrilocal (virilocal, in the husband’s community). If bridewealth is unpaid or only partially paid, all or some of the couple’s children are affiliated with the mother’s group, and residence is usually matrilocal (uxorilocal, wife’s community). In Manggarai, Nage, and Keo, husbands are also expected to perform bride-service for their wives’ parents and may be required to reside with them until bridewealth obligations are completely fulfilled.

Inheritance of land and movable property is generally patrilineal, with matrilineal Tana ‘Ai constituting a notable exception. Property is commonly divided among sons, with the eldest son often inheriting the parental house. Among the Ngadha, however, the house passes either to the first child to marry or to the eldest child who remains resident in the household. Although women typically do not inherit land, in Ngadha, Nage, and Keo they may receive a plot from their fathers at marriage, which can later be transmitted to their children. In parts of Keo and Nage, widows may be recognized as temporary heirs until their sons reach adulthood. In these same regions, when a descent group becomes extinct, the children and descendants of women who married out may assert claims to the estate. Where hereditary offices exist, they are usually transmitted from father to son.

Flores Society and Kinship

Most ethno-linguistic groups on Flores are organized into named patrilineal descent groups, or clans, which may be concentrated in a single village but are more commonly distributed across several settlements. In central Flores, both the Ngadha and Nage have been described as ambilineal or cognatic: the former showing a preference for matrilineal affiliation, the latter for patrilineal affiliation. Endenese clans have been characterized by different researchers as either patrilineal or ambilineal, while in patrilineal Sikka a mother’s natal group retains important ritual rights and obligations toward her children. In ambilineal systems, group membership is largely determined by the payment of bridewealth; when bridewealth is not paid, children are affiliated with their mother’s group. In parts of the Nage region, men may claim and maintain membership in two or more clans simultaneously. Fully matrilineal descent is reported only for Tana ‘Ai. Although the Lio are generally described as patrilineal, some areas exhibit a form of double descent, with distinct patrilineal and matrilineal clans. In nearly all regions, clans are totemic, observing specific taboos against the killing or consumption of particular animals or plants. [Source: Gregory Forth, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Across Flores, societies are commonly divided into hereditary and endogamous ranks, usually three in number and often described as nobles, commoners, and slaves. In Nage and Keo, a distinct class of commoners is less clearly defined, though clan and village leaders are nevertheless regarded as forming a nobility. Among the Ngadha, rank is determined by the status of one’s mother. Those formerly labeled as slaves are more accurately described as hereditary servants, descended from war captives or individuals acquired through purchase; in earlier times, debt could also lead to enslavement. Although slavery was formally abolished during the Dutch colonial period, hereditary distinctions of rank continue to be socially recognized. Aside from ritual and curing specialists, positions based on personal achievement rather than inherited status are largely a modern development.

With the exception of the Ngadha, kinship terminology on Flores generally follows a pattern in which parents are grouped together with their same-sex siblings, while opposite-sex siblings are distinguished. Among the Ngadha, parents are clearly differentiated from their siblings. In many societies, men also use the same term for sisters and certain categories of female cousins, while applying a different term to another category of cross-cousins. This reflects a marriage system in which men are expected to take wives from specific “wife-giving” groups and to avoid marrying women from groups that have previously received wives from their own. At the same time, many kinship systems also show more flexible or symmetrical features by equating certain affinal relatives, such as a wife’s brother with a sister’s husband. Relatives in alternate generations are often grouped together as well, a pattern that among the Nage, Keo, and Lio extends across several generations.

Marriage rules generally require people to marry outside their descent group or clan, except among the Ngadha, who prefer marriage within their own group, even at close genealogical levels. The neighboring Nage allow marriage between distantly related members of the same clan, though most marriages still occur between different clans. In Sikka, marriage within the same village is preferred, especially among commoners. Traditionally, marriage with a mother’s brother’s daughter was considered ideal. In Manggarai, this type of marriage was common mainly among nobles and was obligatory only for the eldest son. Marriage with sisters and certain female cousins is prohibited, though in some areas marriage with other cousins is allowed if clan exogamy rules are not violated. The Ngadha permit marriage with both parallel and cross-cousins.

Since the early twentieth century, the Catholic Church has prohibited marriage between all first cousins and has also banned polygyny, which was formerly practiced by wealthy and high-ranking men in many parts of Flores. Marriage everywhere involves bridewealth, usually paid in buffalo, horses or other livestock, metal goods, and in eastern Flores, elephant tusks. In the past, bridewealth among elites could also include slaves. The bride’s group reciprocates with counter-gifts, mainly in the form of decorated textiles, and among the Nage, Keo, and Sikka also pigs. In Keo and Nage, additional payments are required upon the death of either spouse. The only exception to the practice of bridewealth is the matrilineal society of Tana ‘Ai.

Flores Political and Social Organization

Small, early state formations ruled by indigenous leaders or rajas existed in Sikka, Ende, and Larantuka at the eastern tip of Flores and persisted into the colonial or early national periods. Larger political units also developed in Manggarai, where thirty-nine principalities (dalu) encompassed multiple subdivisions and villages, each headed by a noble lineage. Elsewhere on the island, political authority rarely extended beyond the clan or village level, although marriage ties and shared clan affiliations formed the basis for broader political and military alliances. In several regions, leadership followed a pattern of diarchy, with authority divided between complementary secular and ritual leaders, though this arrangement was not universal. In many areas, an official commonly translated as the “lord of the land” or “lord of the earth” exercised primarily religious authority over land and agricultural matters, distinct from secular political leadership. [Source: Gregory Forth, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Where rajas or other rulers existed, they presided over the resolution of disputes. In other areas, conflict was settled by clan heads, village leaders, or a combination of authorities when disputes involved multiple groups. Sanctions typically took the form of fines or the provision of animals for sacrifice, intended to placate spiritual forces believed to have been offended by the transgression.

Land has long been the principal source of conflict among individuals and local groups throughout Flores. In the past, disputes over territory between political domains or ethno-linguistic groups frequently escalated into armed conflict. In some regions, traditional warfare included head-hunting, and captives—women and children included—were taken as slaves. External demand for slaves, exchanged for precious metals and other goods such as firearms, appears to have intensified interregional warfare during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Villages and Houses of Flores

Except in coastal areas, villages on Flores are typically situated on elevated sites that offer greater protection from attack. Most villages follow a rectangular layout, consisting of two rows of rectangular houses facing one another across a central plaza. The number of houses may range from only a few to several dozen. In Keo and other parts of central Flores, there is a tendency to establish “double settlements,” in which two villages are built end to end or in close proximity. Larger villages commonly include specialized ritual structures, and the central plaza usually contains wooden posts, stone pillars, or similar features—such as forked posts in Nage and Keo or stone columns in Sikka and Lio—that function as focal points for sacrificial rites. Traditional villages in Ende and Sikka also included a men’s house used as a dormitory for boys and unmarried men; in Ende, additional buildings were used to store the bones of ancestors. [Source: Gregory Forth, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

The Manggarai region is distinctive in several respects. Traditional Manggarai villages were circular, with houses arranged around a central ceremonial house and a banyan tree. Historically, a village could consist of a single large conical house occupied by members of a totemic, exogamous, patrilineal clan, and was associated with extensive circular fields divided into triangular sections.

In many parts of Flores, some individuals live temporarily or permanently outside the main village, either in isolated houses or in small clusters of field huts near cultivated land. This dispersed settlement pattern is characteristic of Tana ‘Ai in eastern Sikka, where families typically reside in single-house compounds surrounded by their fields.

Over the course of the twentieth century, residential patterns across Flores have changed markedly. Houses have become smaller and accommodate fewer residents, and many settlements have relocated from hilltops to lower elevations closer to modern roads. Since the 1970s, increasing numbers of people have replaced traditional wooden, bamboo, and thatch dwellings with houses built on concrete foundations, with masonry walls and metal roofs, often constructed along roadsides outside former village sites.

Art and Culture in Flores

Art is mainly in the form of decorated textiles produced by women. Men carve geometric designs on house and sacrificial posts and create wooden statues of ceremonial significance. Major rituals feature instrumental music with gongs, drums, and sometimes bamboo flutes. Song and dance are also performed by both men and women.

Particularly valued were women’s skirts known as lawo butu to the Ngada and Lavo Pundi to the Lio or Ende peoples. The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains women’s skirt made by the Lamaholot people in the late 19th–early 20th centuries. Made of cotton, it measures 132.1 x 159.4 centimeters (52 x 62.75 inches). A lavo pundi in the museum’s collection made by the Ende people dates to the early 20th century. It is made from Cotton and measures (132.1 x 167.6 centimeters (52 x 66 inches). [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Among several Flores groups, beads used to adorn textiles were highly valued and reused for generations. The Metropolitan Museum of Art reports: According to oral tradition, beads, along with other forms of wealth, originally grew on a single tree planted by two orphans. Cut down by greedy villagers, the tree fell in such a way that nearly all the wealth it carried was lost to the island of Java and only the beads remained on Flores.. Ikat designs are typically organized into a banded pattern seen in textiles throughout the Lesser Sunda Islands (Nusa Tenggara).

Traditional Ngada Clothing

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a lawo butu (lawo ngaza, woman's ceremonial skirt) made by the Ngada people of Flores in the late 19th- or early-20th-century from cotton, glass beads, chambered-nautilus shell, nassa shells. It measures 187.96×76.2 centimeters (74 inches high and 30 inches wide. Eric Kjellgren wrote: Worn by aristocratic women on important ceremonial occasions, the intricately beaded ikat skirts known as lawo butu were among the most treasured objects of the Ngada people of Flores. Unlike virtually all other Indonesian textiles, which are produced only by women, lawo butu were created with the participation of both sexes. The patterned ikat cloth was dyed and woven exclusively by women of the highest social class, the gae meze, whose members alone were allowed to wear the finished skirts. Men created and attached the elaborate beadwork appliques.[Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Intended from the outset to become heirloom treasures of the village clans, lawo butu were costly and precious objects. Although they were women 's garments, each was commissioned by a male clan leader of high status. After his death, the skirt was given his name, which was passed down, along with the skirt, to succeeding generations. For this reason lawo butu were sometimes referred to as lawo ngaza (named skirts). To allow the wearer's limbs to move freely when performing complex dance movements during ceremonies, the lawo butu was worn at the waist, secured by a keru (belt), or hung loosely from the shoulders, tied on by a row of kodo-thick cotton threads incorporated into the body of the textile-such as those that appear at the top of the present work.

Lawo butu were also used in connection with the birth of noble children, where they were employed to ceremonially receive the child during its formal introduction to the community. When not in use, lawo butu were carefully preserved in the clan house along with other treasures such as gold ornaments.

Believed to be of supernatural origin, the beads used to adorn lawo butu were valued as highly as gold and were used and reused for generations. In some cases, beadwork appliques from older skirts whose fabric had worn out were preserved and used in the creation of a new lawo butu. According to Ngada oral tradition, beads, along with other forms of wealth, originally grew on a single tree planted by two orphans. Cut down by greedy villagers, the tree fell in such a way that nearly all the wealth it carried was lost to the island of Java and only the beads remained on Flores, where they were used to adorn the lawo butu. The beadwork appliques on the present work, like those of other lawo butu, consist of a grid like pattern of hexagonal or diamond-shaped motifs, identified in some sources as stylized representations of spiders or mosquitos, creatures that symbolize the physical manifestation of human souls (mae). 9 These are adorned with radiating strands of free-floating beads attached at their ends to small white nassa shells; a string of beads tipped with a bangle made from the iridescent shell of the chambered nautilus adorns the center of each hexagon. When the skirt was worn the loosely attached strands of beads gently swayed, accentuating the movements of the dancer.

The larger geometric motifs are interspersed with delicately rendered images of humans, birds, and horses whose heads and extremities are also formed from nassa shells. The Ngada people today are Christian, and lawo butu have not been made for several decades. The precise interpretation of the skirts' imagery is uncertain. The human figures, however, likely represent ancestors. Horses, known asjara, were a symbol of wealth and rank and, in former times, were essential to hunting, warfare, and male ceremonial activities. The birds are probably depictions of domestic chickens, which were the most common sacrificial animals at ceremonies and, formerly, reportedly symbolized slaves (ho'o) inherited by the noble child whom the skirt enfolded in the introduction ritual. Executed with exacting clarity and precision, the intricate ikat designs are organized into a complex series of narrow horizontal bands. This distinctive banded patterning appears widely in textiles throughout eastern Indonesia and likely represents the ancient, indigenous aesthetic of the region.

Traditional Nage Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains wood sculptures of ancestral couples (Ana Deo) dating to the late 19th–early 20th century and made by the Nage people. One measures 25.4×53.3×20.3 centimeters (10 inches high, 21 inches wide and 8 inches deep). Another is (29.8 centimeters (11 inches) tall. Describing one of the works, Eric Kjellgren wrote: Likely depicting the founders of a village clan, this extraordinary couple from the Nage people of Flores Island seem to gaze serenely over all they survey. Nage artists formerly created several types of human images, known as ana deo, representing ancestors and other supernatural beings. Separate male and female figures, erected on posts, flanked the entrances to important structures, and other ana deo appeared as part of sculptures associated with ancestral shrines (heda), which stood, and in some cases still stand, in the center of the village.

The original context of the work is uncertain. However, it seems probable that the couple represent ancestral "riders" who formed part of ajara heda, the large ceremonial horse figure that was erected in front of some heda (shrines). Heda were open houselike structures raised on wood pilings and protected by a thatched roof, and were primarily used to house and display the horns and skulls of water buffalo, which were sacrificed as part of major ceremonies. wood horse images were raised on posts that took the place of the animals' front and back legs, and the heads, tails, and bodies were frequently inlaid with fragments of Chinese porcelain, a precious material obtained through trade. The eyes of the present figures likely once held similar inlays of porcelain or shell. The greatly elongated bodies of thejara heda suggest that the images simultaneously portray both horses and naga, supernatural serpents who conferred wealth and power and served as guardians for prominent villages.

A ceremonial horse image (jara heda) was photographed standing before the entrance to a raised shrine in a Nage village in the late 1980s. Ridden by a male and female ancestral couple, the horse was carved in 1985 to replace an earlier figure, which had become damaged. A second pair of ancestor figures, whose age and significance are unknown and whose postures closely resemble those displayed in the shrine entrance.

Many Jara heda are riderless, but some are carved with ana deo seated on their backs. The rider is typically a single male figure, representing the clan founder, mounted astride the horse's neck with his legs stretching downward on either side of the animal 's body. In some instances he is accompanied by his wife, who is shown behind him riding sidesaddle. The posture of the present ancestral pair, seated side by side with legs drawn in toward the body, is unusual for such equestrian figures.

Two figures similarly positioned appear at the entrance to the raised shrine shown in figure 67. Whether the Metropolitan 's pair represents an architectural carving, a freestanding work of unknown significance, or an ancestral couple cut from ajara heda and later preserved as a clan treasure is unclear. Whatever the work's original purpose, the quiet dignity of the figures, the man's arm clasped around his consort 's shoulder in a gesture of tender embrace, makes this a compelling work of sculpture.

Work and Economic Activity on Flores

Agriculture in Flores is mainly in form or swidden )slash-and-burn) cultivation and and dry-field horticulture. Major crops include rice, maize, millet and other cereals, as well as tubers and vegetables. Prior to the twentieth century, maize was the principal staple, but it has since been largely supplanted by irrigated rice. Irrigation systems were introduced during the Dutch colonial period, beginning in the 1920s in Manggarai and Ngadha, the 1930s in Nage, and as late as 1947 in the Ende and Lio regions. Rice holds particular ritual importance and is required for ceremonial and festive occasions. Palm wine (toddy) and distilled gin, produced from Arenga and lontar palms tapped across the island, are also consumed in ritual contexts. [Source: Gregory Forth, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Domestic Animals include water buffalo—more common in western and central Flores than in the east—as well as horses, pigs, goats, dogs, cats, poultry, and, in drier areas, sheep. Cattle were introduced by the Dutch in the early twentieth century. Men hunt wild pigs, deer, feral livestock, and smaller animals using spears, bows, blowpipes, and, in some regions, harpoons with detachable metal points; snares, traps, and nets are also employed. Coastal communities practice marine fishing, while highland populations engage in freshwater fishing using lines, traps, and weirs, and more recently electric devices. Freshwater resources, however, have become increasingly depleted.

Cash crops grown in higher-rainfall inland areas include coffee, cloves, candlenut, vanilla, and cacao. In coastal regions, the Dutch promoted coconut cultivation for copra production. Today, surplus rice is marketed through village cooperatives, which also serve as outlets for rice purchases. Some commercial fishing exists, though it is largely conducted by outsiders such as Butonese, Makassarese, and Chinese fishers. In parts of central Flores, livestock are raised partly for export. Since the late twentieth century, tourism has become economically significant in certain areas, most notably Labuan Bajo, a gateway to Komodo Island and its population of Komodo dragons.

In most regions, women produce decorated cotton textiles primarily for local use. The Mbai area on the north-central coast (Nagekeo Regency) is especially renowned for brocaded men’s cloths. Some communities, including Riung and Tonggo, have traditionally specialized in pottery production. Other localized crafts include iron and gold smithing, basketry and mat weaving, the manufacture of vessels for eating and drinking, and the production of traditional weapons.

Trade between coastal and highland communities traditionally involved salt, lime, betel, and other coastal products traded for agricultural surpluses. Today, these goods are widely sold in weekly local markets alongside fresh and dried fish, small livestock (such as pigs, dogs, goats, and poultry), fruits and vegetables, locally woven textiles, and imported consumer items. Many villages also have small shops and kiosks. In some interior regions, fresh fish is available daily through traders who travel—often by motorcycle—to coastal areas to purchase fish from marine fishermen. Prior to Dutch rule, a regular export trade in slaves existed at several coastal sites, and slaves were also exchanged locally. At Ma’u Mbawa on the south-central coast, Buginese and Goanese traders obtained slaves in exchange for gold, porcelain, gunpowder, and other commodities.

Division of Labor: Hunting and palm-wine tapping are exclusively male activities throughout Flores. In some regions, women participate in certain forms of freshwater and marine fishing. Men generally undertake the heavier tasks of cultivation, such as forest clearing and fence construction, tend larger livestock, build houses and boats, and manufacture tools and weapons. Women carry out most planting, weeding, and harvesting, and are also responsible for weaving, basketry, and mat making, as well as caring for poultry, pigs, and other small livestock. Childcare is primarily a female responsibility, though men also participate. Women are at least as active as men in buying and selling goods in local markets.

Land Rights are typically held corporately by clans, clan segments, or, in some regions, larger groupings of clans claiming descent from common ancestors. Where land is held by distinct clan segments, permission from more inclusive groups may be required for its transfer; among the Ngadha, land may be freely transferred between houses belonging to the same sub-lineage. Individual land rights are also recognized, and land may be alienated for purposes such as the payment of fines or as part of a wife-giver’s counter-gift, particularly in Nage, Keo, and Ngadha. In Sikka, the household constitutes the primary landholding unit, though ultimate rights to unclaimed land rest with the raja or an official known as the “lord of the earth.” In most areas, outsiders may be granted temporary cultivation rights (usufruct) in exchange for modest payments. Control over land is generally exercised by men and male lineage leaders, with the exception of the matrilineal Tana ‘Ai. Beyond cultivation, rights to hunt, fish, and gather forest products are also vested in corporate groups, though permission for others to engage in these activities is usually readily granted.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last updated in January 2026