LAMAHOLOT

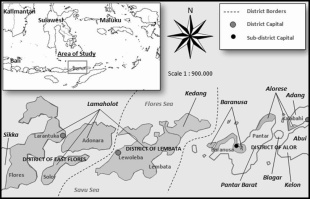

The Lamaholot live in eastern Flores and on the islands of Adonara, Solor, and Lembata between 8°05 and 8°40 S and between 122°35 and 123°45 E, in the Indonesian province of East Nusa Tenggara. Also known as the Ata Kiwan, Holo, Solor, Solorese, Solot, they are farmers and fishermen who hunt whales, manta rays and occasionally dugongs. Most are Catholics; a few are Muslims. In the old days ritual wars were fought to supply heads for ceremonies. [Source: R. H. Barnes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Lamaholot name has been applied to the ethnic group only recently and mainly in academic writing. Most are Roman Catholic, although some are Muslim and a few are Protestant, Hindu, and Buddhist. Some claim to have affiliation with these established religions.

According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Lamahalot population in the mid-2020s was 216,000. Wikipedia listed the number of Lamaholot speakers at between 150,000 and 200,000. The 1980 Census listed both 229,010 and 227,750 as the number of residents in Lamaholot Regency of East Flores — the home territory of the Lamaholot, omitting the ethnically and linguistically distinct Kédang. Excluding Kédang, the average population density of the regency is 81 people per square kilometer. The male-to-female ratio is 80 to 100, compared with 99.6 for the province as a whole. Some areas have suffered drastically from the outmigration of young men seeking wage labor elsewhere. This problem is particularly acute in parts of northern Lembata and eastern Adonara, where the ratio drops to 63 males per 100 females. [Source: Wikipedia, ~]

Linguistically and culturally, the Lamaholot are closely related to the Sikanese to the west and the Kédang to the east. The Lamaholot language comprises three main dialect groups: western (on Flores near the border with Sika), central (eastern Flores, Adonara, and Solor), and eastern (Lembata). Bahasa Alor, spoken in enclaves along the northern coast of Pantar and the western coast of Alor, is at least partially intelligible to Lamaholot speakers.

Lamaholot Language has been placed in the central Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. It is divided into many dialects, some of which are considered distinct languages, such as the Adonara language. The most common dialects are Western Lamaholot (Muhang and Pukaunu), Lamaholot (Lewotaka and Ile Mandiri), Lewo Eleng, and Western Solor. The Lamaholot language serves as a lingua franca for widespread communication among the numerous ethnic groups living in the Larantuka and Solor areas. On the island of Flores, the Lamaholot people speak Larantuka Malay (Bahasa Nagi), a Malay dialect.

RELATED ARTICLES:

LARANTUKA AND LAMALERA IN EAST FLORES: UNUSUAL FESTIVALS, WHALE AND MANTA RAY HUNTS factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL-EASTERN FLORES; ENDE, KELIMUTU. MAUMERE factsanddetails.com

ENDE PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

ALORESE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

ALOR ISLAND factsanddetails.com

FLORES: VOLCANOES, SIGHTS, LABUAN BAJO factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF FLORES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON FLORES factsanddetails.com

WESTERN FLORES: ISLANDS, TRADITIONAL VILLAGES AND HOMO FLORESIERNSIS (HOBBITS) factsanddetails.com

SIKKA PEOPLE OF FLORES: RELIGION, CULTURE, LIFE, SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

MANGGARAI PEOPLE OF FLORES: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

NUSA TENGGARA factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

Lamaholot History

From the 16th century onward, Lamaholot territory became the subject of competing claims by the Sultanate of Makassar, Portugal, and the Netherlands. Until the mid-19th century, Lamaholot areas were largely under Portuguese colonial administration, followed by Dutch rule from 1859 to 1942. Until the middle of the 20th century, the Lamaholot were also formally subject to the authority of the rajas of Larantuka and Adonara. [Source: R. H. Barnes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Islam reached Lamaholot communities at an early date, well before it became firmly established on Java and elsewhere in Indonesia. When the Jesuit priest Baltasar Diaz visited Solor in 1559, he reported the presence of a mosque and a substantial Muslim population. The Portuguese Dominicans established a mission on Solor in 1561 and built a fort there in 1566. Prior to Portuguese involvement, Lamaholot societies had already been influenced by Hindu-Javanese culture: Larantuka on Flores was said to have been conquered by a Majapahit fleet in 1357, and Solor is mentioned in the Negarakertagama as a Majapahit dependency. In the 16th century, some Lamaholot communities acknowledged the suzerainty of the Sultan of Ternate. The Dutch captured the Portuguese fort on Solor in 1613, after which different Lamaholot regions aligned loosely with either the Portuguese or the Dutch until Portugal formally ceded its rights in the Solor Archipelago in 1859.

Patterns of alliance with European powers in the 17th century and later broadly reflected indigenous rivalries between village groupings known as Demonara (today Demon), which tended to align with the Portuguese, and Pajinara (today Paji), who were often Muslim and in some cases maintained treaty relations with the Dutch. Effective Dutch colonial control was finally imposed through a series of military campaigns at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries.

Lamaholot Religion

Most Lamaholot people are Roman Catholics. According to the Christian group Joshua Project 75 percent of Lamahalot are Christian, with Evangelicals, making up 5 to 10 percent of that number. The 1980 census indicates that 81.9 percent of the Lamaholot population identified as Roman Catholic, 17.3 percent as Muslim, and 0.2 percent as Protestant. Only negligible numbers adhered to Hinduism or Buddhism, while 0.6 percent did not declare a religious affiliation. Conversion to Christianity began in the 16th century under Portuguese influence during the colonial period and continued into the 20th century through renewed missionary activity. Muslims constitute a minority, although Islam had been present in the region prior to the 16th century, as evidenced by Portuguese missionary reports noting the existence of a mosque and Muslim communities on the islands. A small number of Lamaholot continue to practice a traditional monotheistic religion centered on belief in Lera Wulan Tanah Ekan—the combined power of the Sun, Moon, and Earth—alongside death cults and shamanistic practices. The Lamaholot also maintain a rich tradition of oral literature and musical expression. [Source: R. H. Barnes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, Wikipedia]

Traditional Religious Beliefs endure and closely resemble those of the neighboring Kedang. In Lamaholot cosmology, God is known as Lera Wulan (Sun–Moon), with a female counterpart, Tana Ekan (Earth). Lera Wulan has increasingly been identified with the God of Christianity and Islam, and alternative names such as Lahatala, Letala, Latala, or Lahatala Dunia—terms of Arabic origin—are also used. Numerous lesser spirits (nitu) are believed to inhabit treetops, large stones, springs, and cavities in the earth. Other important deities include Ile Woka, the god of the mountains, and Hari Botan, the god of the sea.

Ceremonial Life centers on major events such as house construction and boat launching, as well as rituals held in clan ritual houses. Agricultural rites connected with planting and harvesting are conducted in the fields, while coastal communities observe ceremonies marking the start of the annual fishing cycle. Some villages also perform annual purification rituals. In the past, communal ceremonies were directed by the lord of the land, typically within a system of four ritual leaders. Traditional priests and healers are known as molang, while witches (menaka) are believed to cause various forms of misfortune.

Death and Afterlife Beliefs parallel those of the Alorese. The Lamaholot hold that humans possess two souls: the tuber, which can leave the body, and the manger, which cannot. At death, the tuber travels to Lera Wulan or may be consumed by nitu or menaka, while the manger proceeds to the land of the dead. The cosmos is conceived as consisting of multiple levels; upon death, a person is reborn on the level below. After passing through several cycles of life and death, the individual completes the sequence and begins the cycle anew.

Lamaholot Society

Lamaholot society has traditionally been organized around descent, kinship, ritual authority, and communal life. In most Lamaholot areas, social groups are based on patrilineal descent, with identity and inheritance traced through the male line. In the far western areas of Lamaholot territory, however, descent follows a matrilineal pattern. In parts of Adonara, the importance of descent groups has declined, and social life now centers more on the nuclear, patripotestal family, where ultimate authority rests with the father or his male blood relatives. [Source: R. H. Barnes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Kinship systems vary from village to village, but all recorded Lamaholot kinship terminologies are structured around patrilineal descent and include a preference for matrilateral marriage, especially unions with a mother’s brother’s family.

Social organization traditionally emphasized clans that owned land, which were generally the most influential and prosperous groups in the community. Petty nobility once held ritual and political authority, but much of their formal power and influence declined after Indonesian independence. Aside from clan status, social differences based on wealth were not strongly marked. Slavery, however, was formerly widespread and formed an important, though now defunct, aspect of social stratification.

Political life was closely tied to ritual authority. In eastern Flores, the head of the original or landowning clan played a central role in regulating agricultural life, determining the timing of planting and harvesting, and overseeing communal ceremonies. In some areas, this figure also granted permission to clear new land. Across much of the Lamaholot region, authority was traditionally shared among four ritual leaders. The most prominent, the kepala koten, was responsible for internal village affairs, while the kepala kelen handled relations with the outside world. Two other officials, known as hurit (or hurin, hurint) and marang, served primarily as advisers. The authority of these leaders was balanced by the influence of village elders.

During the colonial period, the Dutch reorganized Lamaholot territories into six administrative domains ruled by rajas: Larantuka, Adonara, Trong, Lamahala, Lohayong (Lawayong), and Lamakera. Later administrative reforms placed Trong under the raja of Adonara and Lamahala, Lohayong, and Lamakera under the raja of Larantuka. After independence, the Indonesian government abolished the raja system. Today, Lamaholot communities fall within the Regency of East Flores (Kabupaten Flores Timur), which is divided into districts (kecamatan) governed by appointed officials.

Lamaholot Family and Marriage

Lamaholot households typically consist of a husband and wife, their children, younger brothers or cousins, elderly parents, and other dependents. Traditional social organization is strongly based on patrilineal descent, and ancestry is traced through male lines. These descent lines are further grouped into larger “origin groups” or phratries that structure identity, land rights, and ritual obligations. [Source: R. H. Barnes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

Houses, property, and alliance responsibilities are transmitted according to local rules of descent, most commonly patrilineal. Inheritance practices vary by region, particularly in whether rights pass exclusively to the eldest brother or are shared among male siblings.

Child-rearing is a collective responsibility shared by parents and a wider network of close kin. Children undergo religious rites of passage appropriate to their faith. Before the 20th century, formal education was limited and largely available only in Larantuka, Flores. Since the 1920s, educational access has expanded significantly. Primary schooling is now widespread, while junior and senior high schools, along with Islamic teacher-training institutions, are available within the regency. Some Lamaholot pursue higher education elsewhere in Indonesia.

Marriage practices follow Catholic or Muslim religious rules and are accompanied by elaborate exchanges that serve to build alliances between families and clans. These exchanges vary considerably from region to region and are closely tied to social status. Marriage is typically matrilateral, with spouses drawn from the mother’s kin line, and residence after marriage is generally patrilocal.[9][10] As a result, the nuclear family tends to remain relatively small.

Where both partners are Catholic or Muslim, marriages are solemnized according to the rites of their respective religions. In much of Lamaholot territory, asymmetric marriage alliances were traditionally practiced, involving the exchange of valuables between wife-giving and wife-taking groups. The exact form of these exchanges differs widely, and in some areas they are no longer strictly observed. Catholic doctrine generally prohibits marriage between a mother’s brother’s daughter and a father’s sister’s son. In alliance relations, wife-giving groups are considered socially superior to wife-taking groups. The mother’s close relatives are believed to exert spiritual influence over her children and are treated with special reverence.

Alliance prestations traditionally included elephant tusks given to wife-givers and finely woven ikat cloth presented in return to wife-takers. In some regions, scarce tusks have been replaced by building materials or cash. When exchanges are completed, couples usually reside with the husband’s parents or establish a new household. If no exchange takes place, the couple may initially live with the wife’s family. Divorce is generally easy to arrange, except among Catholics, for whom it is more restricted.

Lamaholot Life, Villages

Traditional Lamaholot settlements in the mountains are surrounded by dense coral hedges. The houses are rectangular with high, steep roofs and skeleton pillars. Before the beginning of the 20th century, long houses were prevalent. Modern settlements are coastal farms with dwellings designed for small families. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

The Indonesia government has consolidated traditional villages and hamlets into administrative units of 1,000 to 2,000 people, each with an elected head, treasurer, and secretary. Bamboo houses with palm-leaf or grass roofs are being replaced by brick-and-cement structures with corrugated iron roofs. The government and Catholic missionaries encourage this transformation.

Lamaholot wear Malay-style clothing. Staple dietary foods includes boiled corn and rice with vegetable and fish seasonings. Men fish, hunt, build boats and houses, and engage in trade. Women weave, make pots, trade produce and cloth, and cook for domestic needs. Men generally assume political roles. Both sexes share the fieldwork. ~

Religion and expressive culture remains alive in Lamaholot rituals, ceremonies, and oral traditions. Their most famous cultural expression is traditional war dance known as Hedung. The arts are largely limited to basketry, music, and the weaving of fine cloth. Decorative carving has largely disappeared. Tattooing is declining. Traditional healers still set bones, repair sprains, and attempt to cope with more serious illness in remote area where hospitals are far away.

Lamaholot Work and Economic Activity

The main occupation of Lamaholot people is manual tropical farming. Maize is the staple crop, supplemented by rice, millet, yam, cassava, sweet potato, legumes, pumpkin, various fruits, and vegetables. Copra, tamarind, spices and candlenuts are raised as cash crops. Cotton and indigo are produced locally. Palms have many uses in construction and food provision. Shark fins, bird nests and deer antlers are collected and sold to traders for the Chinese food and medicine market. Wealth and power is mainly in the hands of a few landowning clans that used to own slaves. Schoolteachers and government workers have stable, regular income. [Source: R. H. Barnes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Fishing is important. In the Lamalera village on Lomblen island and Lamakera village on Solor island people hunt whales and manta ray from relatively small boats. Dugong are taken along protected coasts. Domestic animals include pigs, chickens, goats, sheep, dogs, and buffalo. Deer and wild pigs are hunted. Residents of a number of coastal villages specialize in intermediary trade in textiles, clothing and agricultural implements.

Many Lamaholot communities are known for specialized crafts, including pottery, blacksmithing, and the weaving and dyeing of both coarse and finely patterned ikat textiles. Certain villages are particularly skilled in carpentry and boat building, reflecting the importance of both agriculture and maritime life in the region.

Trade plays a significant role in Lamaholot economic life, especially in coastal settlements such as Lamahala, Trong, Adonara, Lamakera, and Solor. These villages regularly engage in regional exchange networks. A common pattern involves upland communities trading agricultural produce, coconuts, and goats with coastal villages in return for fish and manufactured goods. Weekly markets serve as important hubs for the exchange of everyday commodities and foodstuffs, while permanent shops—often owned by Chinese merchants—are found in larger towns.

Land tenure practices vary across the Lamaholot region. In eastern Flores, village land is typically owned by the dominant clan and is divided and allocated annually by the lord of the land. In other areas, landholding arrangements are less clearly defined. Generally, land is associated with the village as a whole, while individual usage rights are established through clearing, cultivating, and maintaining fields. In recent decades, government policies have encouraged the clearing of previously unused or unsafe land and promoted the introduction of concepts of individual land ownership.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026