MANGGARAI

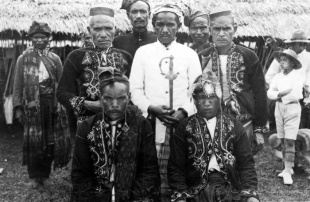

The Manggarai live in western Flores and are the predominate ethnic group there. They have traditionally lived in circular villages that enclose a central square and ceremonial house and have traditionally raised maize and rice in slash-and-burn fields. Their society has traditionally been divided into three groups: nobles, commoners and slaves. Although slavery no long exists to have a slave as an ancestor equates to low status. The Manggarai sometimes refer to themselves as Ata Manggarai, which means 'people of Manggarai'. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

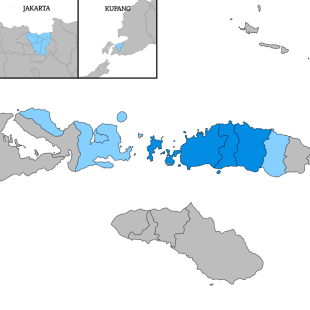

According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Manggarai population is the early 2000s was 809,000. Wikipedia lists their total population at 725,000. In 1981 their population was estimated at 400,000. By the late 20th century, the Manggarai numbered about 500,000. The Manggarai people live in Greater Manggarai, which consists of three regencies: West Manggarai, Manggarai, and East Manggarai. Manggarai people can also be found near the border with Ngada Regency and in Bima Regency. Manggarai settlements cover more than 6,700 square kilometers — nearly one-third of Flores. Manggarai people can also be found on Komodo Island and in Bima and Ngada Regencies. Some have migrated to Kupang and Jakarta. The Makassar and Bimanese have lived among the Manggarai for some time. [Source: Wikipedia]

Language spoken in the Manggarai region is known as Tombo Manggarai. It comprises around 43 sub-dialects grouped into five main dialect clusters — Western Manggarai, Central West Manggarai, Central Manggarai, East Manggarai, and Far East Manggarai — and is markedly distinct from both Indonesian and the languages of neighboring ethnic groups to the east. Far East Manggarai, which is separated from the other dialects by the Rembong language area, is spoken in the north-central part of Flores and has approximately 300,000 speakers. In addition, about 5,000 native speakers of the Rongga language live in three settlements in the southern part of East Manggarai Regency. Rongga is often not recognized as a separate language by Manggarai people themselves, as it is commonly regarded as a variety of Manggarai.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FLORES: VOLCANOS, SIGHTS, LABUAN BAJO factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF FLORES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON FLORES factsanddetails.com

WESTERN FLORES: ISLANDS, TRADITIONAL VILLAGES AND HOMO FLORESIERNSIS (HOBBITS) factsanddetails.com

MANGGARAI PEOPLE OF FLORES: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL-EASTERN FLORES; ENDE, KELIMUTU. MAUMERE factsanddetails.com

ENDE PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

NUSA TENGGARA factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

Manggarai History

According to historical records, Manggarai was ruled at different times by the Bima people of Sumbawa under the Bima Sultanate and by the Makassarese of Sulawesi under the Gowa Sultanate. One of the earliest processes of state formation in Manggarai occurred in the 17th century with the emergence of the tribal kingdom of Todo. Its first ruler, known as Mashur, was of Minangkabau descent and linked to the Gowa Sultanate of Makassar. In 1727, Manggarai was transferred to the Bima Sultanate as a dowry following the marriage of a Makassarese princess, Daeng Tamima, into the Bima royal family.[6] During this period, the coastal settlement of Reo was founded. [Source: Wikipedia]

Under Bima rule, Manggarai was organized into tributary domains governed by kings known as kedaluan and gelarang. Representatives of the sultanate, bearing the title naib, ruled from Reo and Pota and exercised authority over smaller kedaluan known as dalu koe. The most powerful kedaluan—Todo, Cibal, and Bajo—were collectively called dalu mese (major kedaluan) and predated Bima’s hegemonic control. Of these, only Todo exercised authority over subordinate dalu koe, numbering thirteen and collectively known as dalu campulutelu.

The indigenous clan system was formalized under the Bima Sultanate, which reorganized Manggarai into 39 kedaluan (chiefdoms), each headed by a ruler known as a dalu. In 1929, western Flores was separated from the Bima Sultanate. This was followed in the 20th century by Dutch colonial expansion and the subsequent Christianization of Manggarai.

Manggarai Religion

Some Manggarai are Catholics. Some are Muslims. And some hold on to traditional animist beliefs or incorporate them into their Christian and Muslim beliefs. The animist adherents worships ancestor spirits and believe in a supreme god named Mori Karaeng. Religious practitioners known as “ata mbeko” preside over ceremonies, act as healers and are asked to predict the future. In the old days buffalo and pig sacrifices were important but they are not practiced much anymore. ~

According to the Christian group Joshua Project 60 percent of Manggarai are Christians, with a 0.1 to 2 percent being Evangelicals. According to Wikipedia more than 90 percent of the Manggarai population is Catholic, including communities in eastern Manggarai around Borong. Some inhabitants of the western coastal areas are Sunni Muslims. Islam, numbering approximately 33,898 people. Islam most likely spread to Flores through maritime trade routes. The population of central Manggarai, however, traditionally followed indigenous belief systems that were later blended with Catholicism. This religious distribution was shaped in part by a 1783 agreement between Sultan Abdulkadim of Bima and the dalu (king) of Manggarai, which prohibited Muslims—including children of mixed marriages—from residing in the kedaluan (inland domains). As a result, Muslim communities were restricted to coastal settlements such as Reo, Pota, Bari, Gunung Tallo, and Nangalili.

Manggarai believe that the spirits of the dead, called poti, stay where they used to stay when they were alive, especially near the bed, after death. After some time, the poti move to wells, big trees, or crossroads near the house. They watch their grandchildren, but don't disturb the living people. Five days after death, the poti go to Mori Karaeng, the place for the dead. Manggarai people believe that everything in Mori Karaeng is opposite of that in the world of the living. Manggarai break dishes and glasses on the fifth day after death so that the poti has dishes and glasses in good condition in Mori Karaeng.

Major ceremonial celebrations are led by priests and involve the ritual sacrifice of buffalo (ata mbeki), accompanied by ritual dances and mock battles between opposing groups of men dressed in military attire. The Manggarai are known for a rich cycle of rituals that express gratitude for life and well-being. These include: 1) Penti Manggarai, a harvest thanksgiving ceremony; 2) Barong Lodok, a ritual to invite guardian spirits to the center of the lingko (communal fields); 3) Barong Wae, a ceremony calling ancestral spirits to guard water springs; 4) Barong Compang, a nighttime ritual to summon the village guardian spirit; and 5) Wisi Loce, a rite performed to ask invited spirits to pause before the climax of the Penti ceremony.

Manggarai Society

Traditionally, Manggarai society was divided into three social strata: the aristocracy (karaeng), common community members (ata-leke), and descendants of slaves. Manggarai territory is divided into a number of dalu, small principalities that are further subdivided into glarang. The glarang are the basic landowning units and are essentially large patrilineages. The aristocracy is made up of the dominant dalu and glarang lineages. Although slavery no longer exists, descent from slaves remains a sign of lower status. The Manggarai are divided along religious lines, most in the west being Muslim. Kinship and inheritance followed the patrilineal line.

The early political organization of Manggarai society was based on a patrilineal, clan-centered system. Historically, villages were composed of at least two clans, a pattern already evident among the communities of Todo, Bajo, and Cibal. This indigenous system was later formalized under the Bima Sultanate, which reorganized Manggarai into 39 kedaluan (chiefdoms), each headed by a ruler known as a dalu. These chiefdoms were further subdivided into smaller administrative units called gelarang (assistants to the dalu) and beo (village leaders). In addition, sultanate representatives known as naib governed the coastal centers of Reo and Pota; historically, they held higher rank than the dalu and served as intermediaries between local rulers and the sultan. Leadership of each kedaluan was vested in a dominant local patrilineal clan (wa’u), believed to descend from the earliest settlers.

The Manggarai have traditionally recognized a variety of marriage forms, including matrilateral cross-cousin marriage, levirate and sororate marriages, and unions between the children of two sisters and the sons of two brothers, among others. Monogamy predominatea, particularly among Christians, while limited polygyny was permitted among some Muslim and adherents of traditional beliefs.

Manggarai Life

The Manggarai people are primarily farmers who grow crops in the tropical climate. Over time, communities shifted from slash-and-burn cultivation to crop rotation, producing upland rice, legumes, vegetables, coffee, maize, coconuts, cinnamon and tobacco. They also raise buffalo, horses, pigs, and chickens. While most do not fish or hunt, some practice carving, weaving, and metalworking. Manggarai villages often consist of small settlements arranged in a circular layout. In the mountains, people live in swiddens—land cleared by slash-and-burn agriculture—for part of the year. After harvesting the crops, they return to their home villages. Each village has a mosque. The head of the mosque is responsible for ceremonies, religious anniversaries, and the rites of the agricultural cycle. [Source: Joshua Project]

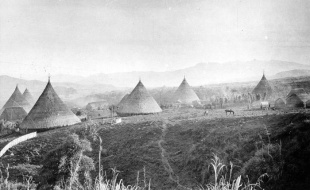

Manggarai villages are organized around a “compang”, a raised stone burial platform surrounded by a stone wall. Facing the platform are traditional houses where important ceremonies and meeting of elders are held. Modern settlements follow a more linear At the center of traditional villages was a circular communal space featuring a large tree—often of the Ficus genus—surrounded by megalithic structures. In the past, a settlement might consist of a single large house accommodating up to 200 people.

Contemporary villages usually comprise between five and twenty houses, round or oval in shape, built on stilts and topped with tall conical roofs reaching approximately nine meters in height. Open spaces within Manggarai settlements were often paved with large stones. In some areas the dead were traditionally buried in circular pits covered with stone slabs.

The staple diet consists mainly of corn porridge accompanied by vegetables and pork (the latter consumed only by non-Muslim Manggarai), along with palm wine (tuak). Rice was traditionally reserved for ceremonial and festive occasions. Water buffalo have traditionally been valued ritual ceremonies. Horses were raised for transport, and pigs and chickens were kept for food. domestic use.

Manggarai Culture

Manggarai livelihoods traditionally included handicrafts such as wood carving, metalworking, and weaving. Initially, the traditional clothing consist of two pieces of fabric, reinforced in front and behind with a cord at the waist and hips. Modern clothing are of the same type as mainstream Indonesian. They also hold important objects such as buffalo-horn-shaped headdresses and cacci whips. ~

The Manggarai people have a traditional folk sport and war dance called caci. It is a form of whip fighting in which two young men usually perform a series of hits and parries with whips and shields in a large field. A caci performance usually begins with a danding dance, followed by the caci warriors displaying their ability to hit and parry. This dance is commonly referred to as Tandak Manggarai and is performed on stage to predict the outcome of the caci competition. [Source: Wikipedia

Many Manggarai live around Ruteng. They wear distinctive black sarongs and raise black haired pigs and miniature horses. They are known for their skill in caci in which combatants with welder-mask-like helmets and rawhide shield beat each other the with one-meter-long whips. ~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026