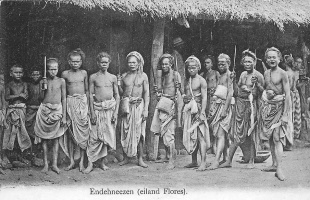

ENDE PEOPLE

The Ende people live in central Flores. Also known as the Endenese, ‘Ata Ende, ‘Ata Jao and Orang Ende, they have traditionally been divided into two groups—the coastal Ende people and the mountain Ende people—and have practiced slash and burn agriculture to raise dry rice, cassava and maize. The climate in the area they inhabit is too dry for wet rice. Coconuts are sometimes produced as a cash crop. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Mountain Ende people used to live in villages organized around a set of altars called “tubu musu ora nata”. Today few villages have these. Livestock—mostly in the firm of pigs, goats and chicken—is raised mostly for consumption and gift-giving purposes. Families with water buffalo, cattle and horses are regarded as relatively rich. Conflicts are often over land ownership with the person who can speak most fluently about its history given the rights to it. ~

The Ende speak a Western Austronesian language in the Bima-Sumba Group. According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Ende population in the 2020s was 134,000 Data from 1986 counted about 200,000 people in Ende Regency, with an estimate of 43,000 coastal Ender in a relatively small area and 20,000 mountain Ende.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CENTRAL-EASTERN FLORES; ENDE, KELIMUTU. MAUMERE factsanddetails.com

LARANTUKA AND LAMALERA IN EAST FLORES: UNUSUAL FESTIVALS, WHALE AND MANTA RAY HUNTS factsanddetails.com

LAMAHOLOT PEOPLE OF FLORES: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

ALORESE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

ALOR ISLAND factsanddetails.com

FLORES: VOLCANOS, SIGHTS, LABUAN BAJO factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF FLORES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON FLORES factsanddetails.com

WESTERN FLORES: ISLANDS, TRADITIONAL VILLAGES AND HOMO FLORESIERNSIS (HOBBITS) factsanddetails.com

SIKKA PEOPLE OF FLORES: RELIGION, CULTURE, LIFE, SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

MANGGARAI PEOPLE OF FLORES: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

NUSA TENGGARA factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

History of the Ende People

Before the arrival of the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, Flores was already integrated into regional trade networks and was used by Javanese merchants, particularly in connection with the sandalwood trade centered on Timor. Portuguese expansion into Southeast Asia began with the capture of Melaka in 1511, and soon afterward the first bishop in Melaka dispatched missionaries to Solor, a small island off the eastern coast of Flores. By the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Islam had also reached parts of central Flores, including Ende.

During this period Flores became a contested frontier between Islamic polities and Portuguese Christian interests. In the early seventeenth century a third power entered the region with the establishment of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1602. In 1613 a Dutch fleet under Apollonius Scot sailed through eastern Indonesia and attacked the Portuguese fortress on Solor, capturing it before proceeding to Kupang. Between roughly 1610 and 1640, control over Solor and nearby areas shifted repeatedly between the Portuguese, based in Larantuka, and the Dutch, but in the long term Dutch influence prevailed.

In the 1620s the fortress on Pulau Ende was destroyed, and thereafter the settlement of Endeh (modern Ende) emerged as the main political and commercial center of central Flores, where the rajadom of Ende was likely already taking shape. By this time Portuguese influence in the region was in decline. In 1793 the Dutch East India Company formally recognized Ende as a rajadom and concluded a contract with its ruler. After the VOC was dissolved in 1799, its territories passed under direct Dutch colonial administration. Until the early twentieth century Dutch rule in Flores involved limited direct intervention, but in 1907 military forces from Kupang were deployed, and the island was fully brought under colonial control through armed pacification.

Ende Religion

According to the Christian group Joshua Project, roughly 60 percent of the Ende are Christians, with the majority being Roman Catholics and a smaller number Protestants, with Evangelicals accounting for an estimated two to five percent. Religious life among the Ende reflects a long history of external influences layered onto older traditions. In the precolonial period, contacts with the Majapahit empire contributed to the diffusion of Hindu elements, while Muslim traders and settlers influenced coastal Ende communities, leading to the spread of Islam between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As a result, religious affiliation and practice vary between coastal and interior regions.

Alongside these world religions, traditional beliefs remain significant. The Ende recognize a supreme being known as nggaë, although this deity is seldom directly invoked in everyday life. More immediate in daily religious practice are the spirits of the ancestors (embu kajo) and other spiritual beings (nitu), who are addressed in prayers and offerings, especially during agricultural rituals, and are believed to influence fertility, health, and harvests. Belief in witches (porho) is also widespread; such figures are thought to live among ordinary people and to cause illness or misfortune, sometimes without clear provocation.

Traditional medicines are called wunu kaju, which literally means "leaves of trees." There are two types of traditional medicine: one used by practitioners (ata marhi), which requires esoteric spells, and the other that does not. People only occasionally go to the coast or the town of Endeh to get modern medicine. When illness is attributed to witchcraft or spiritual attack, sufferers may seek the help of a practitioner known as an ata marhi. These individuals are not ritual specialists by profession but are ordinary community members reputed to possess particular knowledge or abilities for diagnosing and countering such afflictions.

Agricultural life is punctuated by communal ceremonies, most notably the annual yam-eating ritual (kaa ’uwi), which marks both the beginning and the completion of the agricultural cycle. Each village holds this ritual once a year, following a fixed sequence among neighboring communities that is repeated consistently from year to year. At a funeral, a set of valuables called urhu (meaning "head") should be given to the brother of the deceased's mother. He is the first to dig the grave for the corpse. It is believed that the deceased goes to Mount Iya, near the town of Endeh. There is no elaborate myth or legend about the origin of death or the afterlife on Mount Iya. ~

Endenese Society

Ende society is organized around patrilineal descent and relatively egalitarian social relations. Descent groups are known as waja, a term meaning “the old one,” which refers to the patrilineal descendants of a named ancestor. A waja usually extends four to five generations deep and is ideally associated with a specific ritual (nggua) and a ritually owned parcel of land. While waja expresses an important ideological framework for kinship and land, it has little formal social or political function in everyday life. [Source: Satoshi Nakagawa, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Social differentiation among the Ende is limited. People are generally regarded as equal in religious and social status, and there are few formal roles or titles. Although there are hints that slavery (o’o) existed in the past, this status is not publicly acknowledged today and plays no visible role in contemporary social life.

Kinship terminology reflects both patrilineal descent and an ideology of asymmetric marriage alliance, especially preference for marriage with the mother’s brother’s daughter. Fathers and fathers’ brothers are classified together, as are mothers and mothers’ sisters, while distinctions are made between paternal and maternal relatives in ways that express marital asymmetry. These kin categories structure expectations about marriage, alliance, and ritual exchange, even though they do not create rigid social hierarchies.

Political organization is informal. Elder men and women who are respected for their knowledge of genealogy and local history (susu ’embu kajo) play prominent roles in discussions (mbabho), particularly in settling disputes and negotiating bride-wealth. There is no strong internal authority to enforce decisions. Formal administration is largely handled by Indonesian state officials, such as village heads, who are often coastal Ende and socially distant from mountain communities.

Conflict, especially over land, is common and persistent. Disputes are argued through public discussion, with success depending largely on one’s ability to speak convincingly about ancestry and land history. Because there is no definitive mechanism for resolving such conflicts, disagreements are often reopened after time has passed. As a result, ongoing land disputes are a normal feature of Ende community life rather than an exception.

Endenese Marriage and Family

Marriages tend to be viewed as means of firming up already established alliances of families. A big ideal is made about the groom marrying his mother’s brother’s daughter. A bride-price is usually paid. If the groom’s family can not come up with the payment the groom may live in the bride’s family’s house after marriage and fulfill a bride service. Marriage ceremonies and funerals often feature a traditional dance called the “gawi naro” performed along with spontaneous songs “ad-libbed” by a singer at the center of circle of dancers. ~

Despite its ideological importance, matrilateral cross-cousin marriage (mburhu nduu wesa senda) is not considered the most prestigious form of marriage. Greater prestige is attached to marriages with women from groups with whom there is no prior alliance (’ana ’arhé). These marriages require substantial bride-wealth (ngawu), the amount varying by marriage type. If only a small portion can be paid, the husband must live with his father-in-law; if the bride-wealth is fully paid, the wife moves to the husband’s village, where the couple either lives with his parents or establishes a new household.

Today, the domestic unit is typically a nuclear family. Married sons tend to build their houses close to those of their parents, and postmarital residence is virilocal once the required bride-wealth has been paid. Inheritance generally follows patrilineal principles, with the eldest son expected to inherit his father’s property. An exception concerns rights over bride-wealth: only a woman’s full brothers are entitled to claim rights over the bride-wealth paid for her, excluding half-brothers. Childcare is shared by both parents. Older people recall initiation practices such as tooth filing and hair cutting, but these rites are no longer observed in contemporary society.

Ende Villages, Life and Work

The Ende people traditionally practice slash-and-burn agriculture, as irrigated wet-rice farming is limited by chronic water shortages. Their staple foods are cassava (uwi ’ai), rice (’aré), and maize (jawa). Coconut (nio) has long been the most important cash crop. Livestock is raised mainly for consumption and ceremonial exchange rather than for market sale. Most households keep a few pigs—on average about three—and chickens, while goats are less common. Only a small number of households own larger animals such as cattle, horses, or water buffalo.

The division of labor between men and women is relatively flexible. Men usually perform tasks requiring greater physical strength, such as felling trees, while women are responsible for everyday cooking. During ceremonial events, however, men typically prepare meat dishes and women cook rice, reflecting complementary rather than rigid gender roles.

A typical mountain Ende village once consisted of ten to twenty houses arranged around a central yard (wewa). In the past, each house accommodated an extended family, including married brothers and other dependents, but today households are usually nuclear families. Ideally, a village belonged to a single patrilineal group and contained a central altar or set of altars (tubu musu ora nata), though such ritual structures are now rare and most villages include residents of diverse origins.

Ritual and social life is marked by communal dancing. At marriages, funerals, and occasionally during the annual yam ritual (kaa ’uwi), villagers perform the gawi naro, a circle dance accompanied by improvised songs sung by a lead performer at the center. This dance tradition is also reflected in ceremonial textiles, such as the early twentieth-century Ende men’s dance wrappers preserved in museum collections. The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains and Ende man's ceremonial dance wrapper (Luka Smba). Bated to the early 20th century, it is made of Cotton and measures 69.9 x 167.6 centimeters (27.5 x 66 inches)

Trade among mountain Ende communities is limited. Some people travel to the south coast to obtain salt or to coastal villages to purchase fish for resale inland, but beyond these occasional exchanges, commercial activity is minimal. Land tenure combines collective and individual rights. Each ritual community (tana), ideally composed of patrilineally related members tracing their origin to an ancestral village, holds ritual authority over a named territory. These rights are expressed through the yam ritual (nggua ’uwi), which regulates agricultural activities. At the same time, individual land rights are recognized, particularly through the ritual transfer of land from wife givers to wife takers, often from a mother’s brother to his sister’s child. This practice, known as pati weta ti’i ’ané (“giving to a sister, offering to a sister’s son”), links land tenure closely to kinship and marriage alliances.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026