ETHNIC GROUPS ON FLORES

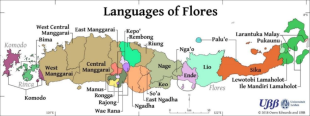

Flores is home to a number of distinct ethno-linguistic groups. Many of their names—such as Manggarai, Ngada, Ende, and Sikka—are today also correspond to modern Indonesian administrative units (regencies). These labels, however, appear to have gained wide currency only in the twentieth century, particularly under colonial and postcolonial administration, rather than reflecting long-standing, island-wide ethnic self-designations. [Source: Gregory Forth, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University; Google AI]

The principal ethnic groups on Flores include the Manggarai of western Flores around Ruteng; the Ngada of the central highlands centered on Bajawa; the Ende and Lio peoples of the central region around Ende; the Sikkanese of eastern Flores around Maumere; and the Lamaholot peoples of the far eastern part of Flores and the surrounding islands, including Larantuka. Closely related populations inhabit neighboring islands, notably Lembata, where communities are well known for traditional whale hunting carried out by hand-thrown harpoons from small boats.

Although these groups share a common Austronesian heritage, each has developed distinctive languages, social institutions, and cultural traditions. Manggarai society is characterized by clan-based organization and strong ancestral and environmental orientations. The Ngada are noted for their prominent ancestor shrines (ngadhu and bhaga) and for ritual practices, such as buffalo sacrifice, that coexist with a deeply rooted Catholic faith. The Ende and Lio peoples are renowned for their ikat textiles and for ritual and cosmological associations with landscape features such as Mount Kelimutu. In eastern Flores, Sikkanese culture reflects a long history of Catholic influence combined with local ritual traditions, while Lamaholot communities in the far east are known for elaborate ancestral ceremonies, warrior traditions, and distinctive dances such as hedung.

Cultural variation across Flores has been shaped by several historical influences. Early Austronesian migrations laid the linguistic and cultural foundations of island societies. Later, contact with Portuguese traders and missionaries had a lasting impact, particularly in eastern Flores and Larantuka, where Catholicism became deeply embedded and gave rise to mixed communities such as the Larantuqueiros (Topasses). Coastal regions were also influenced by interactions with peoples from Sumbawa, Makassar, and other parts of eastern Indonesia, contributing to regional differences in political organization, religion, and material culture.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FLORES: VOLCANOS, SIGHTS, LABUAN BAJO factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF FLORES factsanddetails.com

WESTERN FLORES: ISLANDS, TRADITIONAL VILLAGES AND HOMO FLORESIERNSIS (HOBBITS) factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL-EASTERN FLORES; ENDE, KELIMUTU. MAUMERE factsanddetails.com

LARANTUKA AND LAMALERA IN EAST FLORES: UNUSUAL FESTIVALS, WHALE AND MANTA RAY HUNTS factsanddetails.com

ALORESE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

ALOR ISLAND factsanddetails.com

NUSA TENGGARA factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

Manggarai

The Manggarai live in western Flores. Also known as the Ata Manggarai, they live in circular villages that enclose a central square and ceremonial house and have traditionally raised maize and rice in slash-and-burn fields. Their society has traditionally been divided into three groups: nobles, commoners and slaves. Although slavery no long exists to have a slave as an ancestor equates to low status. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Some are Muslims. Some are Catholic. And some hold on to traditional animist beliefs. The latter group worships ancestor spirits and believe in a supreme god named Mori Karaeng. Religious practitioners known as “ata mbeko” preside over ceremonies, act as healers and are asked to predict the future. In the old days buffalo and pig sacrifices were important but they are not practiced much anymore. ~

Manggarai villages are organized around a “compang”, a raised stone burial platform surrounded by a stone wall. Facing the platform are traditional houses where important ceremonies and meeting of elders are held. They also hold important objects such as buffalo-horn-shaped headdresses and cacci whips. ~

Many Manggarai live around Ruteng. They wear distinctive black sarongs and raise black haired pigs and miniature horses. They practice a former of martial arts called “caic” in which combatants with welder-mask-like helmets and rawhide shield beat each other the with one-meter-long whips. ~

Manggarai believe that the spirits of the dead, called poti, stay where they used to stay when they were alive, especially near the bed, after death. After some time, the poti move to wells, big trees, or crossroads near the house. They watch their grandchildren, but don't disturb the living people. Five days after death, the poti go to Mori Karaeng, the place for the dead. Manggarai people believe that everything in Mori Karaeng is opposite of that in the world of the living. Manggarai break dishes and glasses on the fifth day after death so that the poti has dishes and glasses in good condition in Mori Karaeng.

See Separate Article: MANGGARAI PEOPLE OF FLORES: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

Sikka People

The Sikka people live in the east-central mountains and coastal areas of Flores. Also known as the Ata Bi’ang, Ata Krowe, Sika, Sikka, Sikkanese, they have traditionally been farmers and fishermen who built their villages on ridge tops and were ruled by Catholic rajas until the 1950s. Their villages were once centered around villages houses that contained elaborate carvings, ceremonial drums and gongs and were where male circumcisions were performed. These houses are mostly gone as are traditional residential houses. Much of their land has been deforested and degraded by the overproduction of copra plantation agriculture. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Sikka people Catholicism incorporates many traditional pre-European beliefs such as a pantheon of coupled male and female deities. The Sikka people link the Christian God with traditional concepts of a “sourcefather” and “father of generation” and view the Virgin Mary as his complementary female force. In the old days boys were ritually circumcised and then required to live in the man’s house. ~

Illnesses are believed to be caused by sorcery and attacks by witches and evil spirits. Cures some involve recalling souls, confronting witches and removing objects from the body. After death corpses were traditionally wrapped in cloth or mats and buried in the ground. Coastal dwellers used coffins shaped like boats and placed a coconut or another object above the grave. After death, the Sikka people believe, the soul often is transported to an underworld where it is repeatedly is reborn after undergoing certain ordeals. ~

The Sikka people have some interesting marriage customs. Until the practice was discouraged by the church the preferred union was between a boy and his mother’s brother’s daughter. Marriages have traditionally been sealed by the exchange of bride wealth from the grooms’ family for reciprocal gifts from the bride’s family. The bride-wealth was traditionally expected to be in the form of “male” goods such as elephant tusks, horses, gold or silver goods. The reciprocal gifts were expected to be in the form of “female” goods such as cloth, pigs, rice, furniture and household utensils. The marriage was formally announced by the pinching a pig until it squeals, with the marriage itself often taking place several years later with a Catholic ceremony. A marriage is often initiated or is part of an elaborate exchange of debts and goods, with the most valuable goods being elephant tusks, which may not be bought or sold but only ceremoniously exchanged. A record of the exchanges often corresponds with the formation of alliances in the community. ~

See Separate Article: SIKKA PEOPLE OF FLORES: RELIGION, CULTURE, LIFE, SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

Ata Tana ‘Ai

The Ata Tana ‘Ai live in eastern Flores and are regarded a branch of the Sikka people. Also known as the Ata ‘Iwang. Ata Kangae, Ata Krowe, Krowe, they live primarily in the mountains and practice slash-and burn agriculture, growing rice, maize, and yams. They also raise pigs, chickens and goats, hunt deer and wild pigs in the forest, and collect wild fruit. They trade bamboo, timber, rice and meat for palm wine, gin and consumer goods and foodstuffs. Some raise coffee, spices and copra as cash crops. [Source: E. Douglas Lewis, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Families are defined as a mono, a group that lives in a traditional garden house and is typically made up of a husband and wife and unmarried children and the couple’s parents if they are unable to take care of themselves. Marriage is not marked by any special ritual and there is no bride price or exchange of gifts. Social organization is within clans and large groups called lepos, which are ranked against other lepos. Clans are traditionally headed by women, with men serving primarily as ritual specialists. ~

The Ata Tana ‘Ai believe in a universe with two major realms that were once connected by an umbilical chord: 1) the earth, which has several levels and is regarded as predominately female; and 2) the firmament, which has eight levels and is regarded as male. They also believe in ancestors spirits and dangerous spirits of the forest. Sacrifices and rituals have traditionally been conducted before hunting or entering the forest. The Ata Tana ‘Ai have a highly developed ritual language that is recited at funerals and circumcision and other important life events. ~

Ende People

The Ende people live in central Flores. Also known as the ‘Endenese, Ata Ende, ‘Ata Jao and Orang Ende, they have traditionally been divided into two groups—the coastal Ende people and the mountain Ende people—and have practiced slash and burn agriculture to raise dry rice, cassava and maize. The climate in the area they inhabit is too dry for wet rice. Coconuts are sometimes produced as a cash crop. [Source: Satoshi Nakagawa, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Mountain Ende people used to live in villages organized around a set of altars called “tubu musu ora nata”. Today few villages have these. Livestock—mostly in the firm of pigs, goats and chicken—is raised mostly for consumption and gift-giving purposes. Families with water buffalo, cattle and horses are regarded as relatively rich. Conflicts are often over land ownership with the person who can speak most fluently about its history given the rights to it. ~

Marriages tend to be viewed as means of firming up already established alliances of families. A big ideal is made about the groom marrying his mother’s brother’s daughter. A bride-price is usually paid. If the groom’s family can not come up with the payment the groom may live in the bride’s family’s house after marriage and fulfill a bride service. Marriage ceremonies and funerals often feature a traditional dance called the “gawi naro” performed along with spontaneous songs “ad-libbed” by a singer at the center of circle of dancers. ~

Traditional religious beliefs endure, with recognition of a supreme being named “naggae”, ancestors spirits, animist spirits and witches. Sick people that believe they are victims of witchcraft are sometimes treated in special ceremonies. Agricultural activities are sometime marked by ritual yam eating. ~

See Separate Article: ENDE PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

Ngada

The Ngada are a group that live in the highlands around Bajawa in central Flores, primarily within present-day Ngada Regency. Also known as the Ata Ngada, aNgadha, Nad’a, Nga’da, Bajawa, or Rokka, they are descendants of the indigenous inhabitants of Flores. Coastal Ngada communities have experienced cultural influences from Malay, Bimanese, Buginese, and Makassarese peoples, while more isolated mountain communities have retained stronger elements of traditional belief and practice. Their total population is unclear as they have mixed with other ethnic groups. The Christian group Joshua Project said they numbered 96,000 in the early 2020s. Another sources from the 1990s said there were only around 60,000 of them. The Encyclopedia of Ethnic Groups in Indonesia (2015) adopts a broad definition of “Ngada,” estimating their population at around 155,000 based on 1975 data. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993); Wikipedia]

The Ngada speak the Ngada language, including the Namut–Nginamanu dialect chain, which belongs to the Bima–Sumba group of Austronesian languages. It is closely related to other Central Flores languages, such as Nage–Keo, Ende, Lio, and Palue, as well as to Manggarai. The language and culture of the Ngada were documented in the twentieth century by the missionary and ethnographer Paul Arndt.

Ngada villages feature groupings of “ngadhu”, three-meter-high parasol-like structures, and “bhaga”, miniature thatched roof structures, which together symbolize the presence of important ancestors. In a traditional village high-roofed houses on low stilts are built around an open space with “ngadhu” and bhaga”. The Ngada are mostly Catholics (Joshua Project says 96 percent are Christians) but a number of their traditional beliefs endure, particularly in upland areas. Sometimes buffalos are sacrificed during the planting season to ensure a good season. Special ceremonies are held to mar births, marriages, death and house building.

Traditionally, the Ngada have relied on agriculture, cultivating rice, maize, millet, and a variety of secondary and cash crops, including beans, squash, peanuts, vegetables, and spices. Additional subsistence activities include hunting, gathering, and livestock husbandry. Weaving is widespread, and some individuals engage in metalworking. Plant-based foods form the core of the diet, while meat is generally reserved for ceremonial and festive occasions.

Ngada society is characterized by a matrilineal kinship system, distinguishing it from many neighboring groups on Flores, which are predominantly patrilineal. While most Ngada people live within Ngada Regency, the region is also home to several other ethnic groups, sometimes leading to overlapping or ambiguous classifications. The Ngada are the indigenous population of the Bajawa area. Neighboring communities, including the Riung, Rongga, Nage, Keo, and Palue, are occasionally regarded as subgroups of the Ngada or as closely related populations.

See Traditional Ngada Textiles Under PEOPLE OF FLORES factsanddetails.com

Nage People

The Nage are an indigenous ethnic group of eastern Indonesia, living primarily on Flores Island, especially in present-day Nagekeo Regency, with smaller populations on Timor. They descend from the indigenous inhabitants of Flores and have long interacted with neighboring groups, leading to varying degrees of cultural assimilation. The Nage speak the Nage language, one of the major Austronesian languages of central Flores. Related ethnic groups include the Keo, Ngada and Lio. [Source: Wikipedia]

Traditionally, the Nage practiced manual swidden (slash-and-burn) agriculture, cultivating tubers, rice, and maize, supplemented by hunting and gathering. Until the mid-twentieth century, land was held communally and worked by extended family groups. Settlements typically took the form of clustered villages located on mountain slopes and enclosed by stone walls. Houses were arranged in rectangular formations and linked by open galleries, creating a single residential complex shared by several large families.

Traditional clothing consists of a loincloth or skirt (kain), worn by women wrapped over the breast and by men around the waist. The diet is largely plant-based, centered on cooked grains and tubers seasoned with spices, while meat is usually consumed only during ritual or festive occasions.

The first comprehensive study of Nage society was produced in 1940 by Dutch colonial officer Louis Fontijne, titled Grondvoogden in Kelimado (“Guardians of the Land in Kelimado”). Originally commissioned as an investigation of indigenous land tenure and leadership, it remains the most detailed colonial-era account of Nage social organization and culture.

Scholarly interest was renewed in the late twentieth century by anthropologist Gregory Forth, who revisited the region in the early 1980s while seeking Fontijne’s complete manuscript. Forth later proposed a possible connection between Nage oral traditions concerning the Ebu Gogo, a mythical humanoid creature, and the discovery of Homo floresiensis, an extinct hominin species identified on Flores, contributing to renewed international attention to Nage culture.

According to estimates cited by the Joshua Project, the Nage population in the early 2020s ranged between 76,000 and 80,000. Approximately 80 percent identify as Christian, the majority of whom are Roman Catholic, with a small minority of Evangelicals. Islam and indigenous religious traditions are also practiced by a portion of the population. Elements of traditional agrarian religion have persisted, particularly rituals associated with agriculture. Before planting, ceremonial rites to purify fields and rice seed are performed, traditionally timed to the appearance of the first new moon preceding cultivation.

See Traditional Nage Art Under PEOPLE OF FLORES factsanddetails.com

Lamaholot

The Lamaholot live in eastern Flores and on the islands of Adonara, Solor, and Lembata. Also known as the Ata Kiwan, Holo, Solor, Solorese, Solot, they are farmers and fishermen who hunt whales, manta rays and occasionally dugongs. Most are Catholics; a few are Muslims. In the old days ritual wars were fought to supply heads for ceremonies [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Maize is the staple crop, supplemented dy rice, tubers and vegetables. Copra, tamarind and candlenuts are raised as a cash crop. Shark fins, bird nests and deer antlers are collected and sold to traders for the Chinese food and medicine market. Wealth and power is mainly in the hands of a few landowning clans that used to own slaves. ~

Marriages are conducted in accordance with Catholic and Muslim rules with an elaborate series of exchanges set by social class seen as alliance builders. The nature of the exchanges varies quite a bit from region to region. Religious beliefs are also similar to those of the Kedang. Views about the afterlife are similar to those of the Alorese. Important rituals are held in a clan house to mark the erecting of a house or the launching of a boat. ~

See Separate Article: LAMAHOLOT PEOPLE OF FLORES: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

Palu’e

The Palu’e is a small group that live on the island of Palu’e, which is 15 kilometers off the north coast of Flores. It has little drinking water and embraces Rokatenda, an active volcano that fills the island with steam- and gas-emitting fumaroles and erupted violently in 1928, killing several hundred people. The Palu’e are also known as the Ata Nuha, Ata Nusa, Ata Pulo, Hata Lu’a, Hata Rua, Orang Palu’e. Their name is believed to be derived from the Bugi word for “conically-shaped headdress” (“palu-palu”). [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The Palu’e speak their own unique language and number about 15,000. They have traditionally lived in fortified ridge-top villages for protection from interdomain warfare, piracy and slave raids and farm tubers, mung beans and maize and have been reluctant to grow rice because of an ancient proscription against it. In some places they gather water for crops by collecting steam from volcanic furmoles. Heat from the earth is used like an oven to cook some food. Tapping of the lonta palm is another source of fluid (there is ancient prohibition against distilling the juice). ~

The Palu’e were once famous for their boat-building skills. They built the boats on mountains and ceremoniously dragged them down the slopes to the water. But a lack of trees on their island has curtailed boat construction in recent decades. ~

Palu’e Customs

Palu’e life is defined by taboos and prohibitions, which are passed orally through the generations, warfare involving land disputes, and water buffalo sacrifices. Like other groups in Nusa Tengarra, the Palu’e exchange “male” and “female” goods to seal a marriage. The birth of a child is marked by the ceremonial cutting of a forelock and a symbolically marriage on the third day after birth while tribe prohibitions are recited. For boys there used to be a special ceremony for when they donned their first loincloth. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Battles over land were often timed to coincide with auspicious days on the ceremonial calendar. Men traditionally fought using speaks, flintlocks, bows and arrows and bush knives and women participated by throwing stones. A truce was often declared by some priests after a few minor injuries. Military forces on Flores were often called in before a battle started and the disputes were settled in a court. ~

The religious beliefs and water buffalo sacrifices of the Palu’e are somewhat similar to those of the Toraja and are rooted in myths about ancestors arriving by boats from a distant places long ago. Water buffalo are sacrificed by special priest to bring prosperity. The ritual is often accompanied by the recitation of myths and the ceremonial inauguration of boats. The dead are buried near their homes. If the body has been lost at sea, the trunk of a tree is buried in their place. Many of these ritual were observed by anthropologist decades ago and it is not clear how closely they are adhered to anymore. ~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last updated in January 2026