SIKKA PEOPLE

The Sikka people live in the east-central mountains and coastal areas of Flores. Also known as the Ata Sikka (“Ata” means “people” or “man”), Ata Bi'ang, Ata Krowé, Sika, Sikka and Sikkanese, they have traditionally been farmers and fishermen who built their villages on ridge tops and were ruled by Catholic rajas until the 1950s. Their villages were once centered around villages houses that contained elaborate carvings, ceremonial drums and gongs and were where male circumcisions were performed. These houses are mostly gone as are traditional residential houses. Much of their land has been deforested and degraded by the overproduction of copra plantation agriculture. [Source: James J. Fox and E. Douglas Lewis, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Sikka population in the early 2020s was 264,000. According to the 1980 national census, the total population of the Sikka regency was 219,650. Of this number, approximately 175,000 people speak Sara Sikka, the Sikkanese language. The remaining inhabitants are Lionese, who mainly reside in the western part of the district, and Ata Muhang, who are Lamaholot-speaking people inhabiting the far northeastern region of the district. ~

Language: of the Sikka is Sara Sikka, also known as Sara Way, an Austronesian language. Wurm and Hattori (1983) include it in the Flores-Lembata (Lomblen) subgroup of the Timor area group of Austronesian languages in the Lesser Sunda Islands and Timor. At least three dialects of Sara Sikka have been be identified: (1 the dialect spoken by people in the Sikka Natar region and the village of Sikka on the south coast of Flores,(2) Sara Krowé, spoken in the central hills of the Sikka regency, and 3) Sara Tana 'Ai, spoken by approximately 6,000 people.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FLORES: VOLCANOS, SIGHTS, LABUAN BAJO factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF FLORES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON FLORES factsanddetails.com

WESTERN FLORES: ISLANDS, TRADITIONAL VILLAGES AND HOMO FLORESIERNSIS (HOBBITS) factsanddetails.com

MANGGARAI PEOPLE OF FLORES: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL-EASTERN FLORES; ENDE, KELIMUTU. MAUMERE factsanddetails.com

ENDE PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

LARANTUKA AND LAMALERA IN EAST FLORES: UNUSUAL FESTIVALS, WHALE AND MANTA RAY HUNTS factsanddetails.com

LAMAHOLOT PEOPLE OF FLORES: HISTORY, RELIGION, SOCIETY, LIFE factsanddetails.com

NUSA TENGGARA factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

Where the Sikka People Live

The traditional territory of the Sikka centers is in Sikka Regency in east-central Flores, originally a small indigenous polity of the raja of Sikka, with Maumere serving as the regional urban hub. Contact with the Portuguese from the 16th–17th centuries and later missionary activity shaped local political and religious developments.

The Sikka people inhabit both coastal zones and mountainous interiors within Sikka, a region extending from the north to the south coast of east-central Flores and roughly from Talibura on the northeastern coast westward to the Nanga Bloh River. The landscape is broken and eroded, marked by sharp contrasts between lowlands and uplands. Erratic monsoon patterns and a prolonged dry season produce considerable climatic variation, while porous soils and the scarcity of permanent rivers make agriculture highly dependent on unpredictable rainfall. Across much of western Sikka, the shortage of reliable and well-situated sources of drinking water remains a persistent environmental challenge.

The Sikkanese live between the territories of the Lio to the west and Larantuka to the east. The name “Sikka” derives from Sikka Natar, the “village of Sikka” on the south coast, which served as the center of a Portuguese-Christian polity from the early seventeenth century until 1954. Over time, the term came to be applied more broadly: first to the domain ruled by the raja of Sikka, then to the combined territories of Sikka and its tributary mountain domains of Nita and Kangae (formally amalgamated in 1929), and ultimately to the entire area corresponding roughly to the former Dutch onderafdeling of Maumere and the present-day Indonesian administrative region of Kabupaten Sikka.

Most Sikka people are concentrated in the western part of this territory. The dialect and customs of the Ata Tana ’Ai in the eastern mountains of Sikka are sufficiently distinct to warrant separate treatment. The terms Krowé or Ata Krowé have been used, both by the Sikkanese themselves and by outside observers, in several overlapping ways: to refer to people living in and around Maumere, the main port and administrative center on the north coast; to distinguish non-Christians from Christians (ata serani); and more generally to describe the formerly non-Christian mountain populations (Ata ’Iwang) from Nele eastward to Tana ’Ai, including those of the subordinate rajadom of Kangae. Whether Krowé originally denoted a distinct ethnic group remains unclear. Twentieth-century administrative changes that aligned the Sikka domain with the Maumere region also placed areas with substantial Lio populations under Sikkanese political control, further complicating ethnic boundaries.

History of the Sikka People

According to Sikkanese tradition, the rajadom of Sikka was founded by Don (g) Alésu, the ancestor of the royal house of Sikka Natar. Oral accounts relate that Don Alésu traveled to Malacca, where he converted to Christianity, before returning to Flores to establish the domain of Sikka. In doing so, he is said to have recognized the rulers of Nita and Kangae as his “left” and “right” hands, forming a triadic political order. Documentary sources from 1613 already list Sikka among the Portuguese-affiliated Christian states of the region. During the Dutch colonial period, the domains of Sikka, Nita, and Kangae continued to be recognized as separate political entities until 1929, when Nita and Kangae were formally amalgamated with Sikka under the authority of the raja of Sikka. [Source: James J. Fox and E. Douglas Lewis, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Under Dutch administration, the rajadom of Sikka was granted the status of an autonomous region (daerah swapraja), subject to indirect rule through the raja. During this period, the seat of government was transferred from the coastal village of Sikka Natar to the growing town of Maumere. The last raja to serve as head of government, Ratu Mo’ang Bako Don Josephus Thomas Ximenes da Silva, died in 1952. Within a few years, the rajadom was dissolved, and its territory and population were incorporated into the modern Republic of Indonesia.

In the early 1950s, the political organization of the Maumere region under the raja of Sikka consisted of sixteen parishes, each headed by an official known as a kapitan. These parishes were subdivided into villages, each governed by a village headman (kepala kampung). Alongside this administrative structure existed an older, customary system of authority. As described by Paul Arndt (1933), figures known as tana pu’ang (“lords of the earth”) held ritual rights over land and possessed authoritative knowledge of adat (customary law). The tana pu’ang were regarded as descendants of the original founders of village territories and were traditionally viewed as standing in tension with the raja and his representatives.

During the period of the rajadom, mechanisms of social control included adjudication by the raja, his officials, village headmen, and village elders, among them the tana pu’ang. Judicial procedures sometimes involved oaths and ordeals (jaji). In western Sikka, villages were historically engaged in limited warfare with neighboring Lio communities along their shared borders. Arndt reported that enemy heads were once displayed at village entrances following raids and later symbolically replaced with coconuts in ritual performances. Contemporary Sikkanese, however, dispute these accounts and maintain that headhunting was practiced exclusively by the Lio rather than by the Sikkanese themselves.

Sikka Religion

According to the Christian group Joshua Project 100 percent of Sikka are Christians, with 10 to 50 percent being Evangelical. Most are Sikka are Roman Catholics. Catholicism incorporates many traditional pre-European beliefs such as a pantheon of coupled male and female deities. The Sikka people link the Christian God with traditional concepts of a “sourcefather” and “father of generation” and view the Virgin Mary as his complementary female force. [Source: James J. Fox and E. Douglas Lewis, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Roman Catholicism was introduced in the 16th century by Portuguese and made headway through missionary activity and later Catholic mission presence across Flores. Catholicism has been closely associated with Sikkanese political authority since the early seventeenth century, when it became linked to the rule of the rajas of Sikka. As a result, Catholic ritual came to dominate public ceremonial life, though it did not entirely displace older religious ideas. In contemporary practice, rosary associations devoted to the Virgin Mary play an important role and are often understood as restoring a feminine complement to amapu, thereby maintaining a sense of balance familiar from older cosmology.

Belief in generally benevolent ancestral spirits remains widespread, though Sikkanese traditions also speak of female spirits, or spirit pairs with dangerous female aspects, that pose particular risks to humans. Important elements of ancestral and local religious practice include beliefs in guardian spirits associated with land and houses (known by various local names), ritual obligations tied to kinship and territory, and persistent concerns about witchcraft and malevolent individuals. In everyday life, ceremonies, and major life-cycle events, Christian observances commonly coexist with, and are interwoven into, customary (adat) practices rather than fully replacing them.

Sikka Ceremonies

In the old days boys were ritually circumcised and then required to live in the man’s house. According to Arndt, circumcision and initiation rites were overseen by the tana pu’ang (“lord of the earth”).

Illness is often understood as having spiritual causes, including sorcery, attacks by witches, or harmful encounters with spirits. Traditional healing may involve recalling a lost soul, confronting or identifying witches, or extracting intrusive objects believed to have been placed in the body. Two main types of ritual healers were recognized: ata rawing, benign healers of either sex, and ata busung, predominantly male specialists capable of diagnosing illness, extracting harmful objects, identifying witches, and recalling souls. In contemporary Sikka Natar, a small number of women are still recognized as ata rawing. Illness was traditionally attributed to contact with sorcerous substances (uru), witchcraft, or dangerous encounters between the soul and spirits.

Funerary Practices reflect both continuity and change. After death, the dead were traditionally wrapped in cloth or mats and buried in the ground; along the coast, coffins shaped like boats were sometimes used, with a coconut or other object placed above the grave. In traditional belief, the soul was thought to journey to an underworld, where it underwent ordeals and cycles of death and rebirth.Today, burials generally follow Catholic forms, yet funerals remain key occasions for resolving outstanding obligations, particularly unpaid bridewealth and reciprocal prestations.

Sikka Society and Kinship

Sikkanese society was traditionally stratified into three main classes: nobles (ata mo’ang), who were related to the raja of Sikka and to the former ruling houses of Nita and Kangae; freemen or commoners (ata riwung); and, formerly, slaves (ata maha), consisting largely of debtors and individuals captured during warfare. [Source: James J. Fox and E. Douglas Lewis, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

In central Sikka, descent is primarily patrilineal (a: a child belongs to the father’s descent group. The mother’s descent group, however, retains certain ritual rights and obligations toward the children of its women who marry outside the group. In particular, the mother’s brother must receive a ceremonial prestation from his sister’s husband’s group at the birth of each child. This payment extinguishes any potential claim the mother’s group might otherwise assert over the child’s membership. Communities are organized into large, named descent groups (ku’at or ku’at wungung) that are nonlocalized and nonexogamous. Each group traces its origin to a founding ancestor, maintains its own historical traditions, and observes a limited set of ritual prohibitions. In Sikka Natar, the village of Sikka on the south coast, these ku’at wungung are further associated with specific wards within the settlement.

Kinship terminology in western Sikka reflects these social distinctions and marriage rules. Published accounts by Calon and Arndt show that father and father’s brother are grouped together under the term ama, while the mother’s brother is distinguished as pulamé or tiu. Mother and mother’s sister are both called ina, in contrast to the father’s sister, who is referred to as ’a’a. Cross-cousins are distinguished from parallel cousins and are further classified according to the sex of the speaker. Cross-cousins who are potential marriage partners—classificatorily the mother’s brother’s daughter and the father’s sister’s son—address one another as ipar or ipar tu’ang. While these principles are widely shared, minor variations in kin terminology and classification exist among different communities in central Sikka.

Sikka Marriage and Family

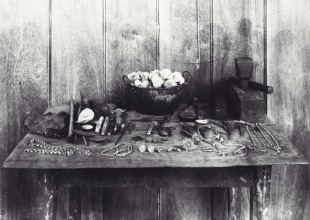

The Sikka people have some interesting marriage customs. Until the practice was discouraged by the church the preferred union was between a boy and his mother’s brother’s daughter. Marriages have traditionally been sealed by the exchange of bride wealth from the grooms’ family for reciprocal gifts from the bride’s family. The bride-wealth was traditionally expected to be in the form of “male” goods such as elephant tusks, horses, gold or silver goods. The reciprocal gifts were expected to be in the form of “female” goods such as cloth, pigs, rice, furniture and household utensils. The marriage was formally announced by the pinching a pig until it squeals, with the marriage itself often taking place several years later with a Catholic ceremony.

Marriage is monogamous and subject to strict prohibitions: unions are forbidden between In Sikka Natar, people observe the rule of empat lapis (“four layers”), which permits marriage only between individuals related no more closely than third cousins. Relations between allied groups in central Sikka—most elaborately in Sikka Natar—are structured through complex cycles of ceremonial exchange and ritual service. These exchanges are initiated by bride-wealth and its counterprestations and create enduring affinal obligations.

Elephant tusks and ceremonial textiles (’utang) are especially important within this exchange system. Elephant tusks are nonconsumable items whose circulation records the history of alliances within a community. Ceremonial textiles, by contrast, are consumable goods: they must be cut, sewn into sarongs, and worn by the women who receive them, requiring continual replacement through women’s labor.

Throughout Sikka, marriage ideally occurs within the village, although royal and noble houses often arrange marriages across village boundaries to enhance political influence by acting as wife-givers to other noble families. According to Arndt, a man may reside for a year or more in his wife’s parental home, or alternate residence between his own parents’ and his wife’s parents’ households, before establishing an independent household—a practice that continues in Sikka Natar.

A household may include the elderly parents of either spouse, along with a recently married child and spouse. While royal households were reported by ten Dam and Arndt to number as many as fifty individuals, the average household size in Nita was about ten. Property is generally divided among male siblings, though an elder brother may manage the household’s dry fields on behalf of his brothers in order to keep them intact for another generation. One child, together with a spouse, customarily remains in the parental home and ultimately inherits the house.

Sikkense Life, Villages and Work

Sikkanese daily life combines subsistence agriculture, small-scale fishing, and local trade. In the uplands, communities practice shifting cultivation and tend garden crops such as maize and vegetables, while coastal settlements place greater emphasis on fishing and market exchange. Villages are sustained by strong kinship networks and enduring social hierarchies, though settlement patterns vary widely—from linear villages along the coast or roads to compact mountain hamlets organized around communal sacred spaces. In some interior areas, megalithic markers continue to signal ritual centers. Weaving and local textile traditions, including ikat and other patterned cloths, remain culturally significant, and Sikkanese speech, idioms, and proverbs continue to serve as important markers of identity, even as Bahasa Indonesia is increasingly used in public life. [Source: James J. Fox and E. Douglas Lewis, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Joshua Project]

In the central saddle of the district, villages are often situated along ridge crests or other elevated points, while elsewhere they extend along roads or parallel the coastline. Houses are typically arranged in rows flanking a road or major footpath, with traditional village centers marked by one or more large offering stones (mahé). Earlier accounts describe elaborately carved ceremonial houses (woga) that contained ritual objects such as gongs, drums, and shields; these structures were reserved for men and served as venues for male circumcision in many non-Christian villages. Such buildings have disappeared from central Sikka, though Arndt suggests that villages were once divided into clan quarters, each with a designated clan house. Traditional dwellings are rectangular and raised on posts about a meter or more above the ground. In western Sikka, houses commonly consist of a front gallery (tédang) and an inner room (uné), each further subdivided. Increasingly, however, these houses have been replaced by structures built directly on packed earth or concrete foundations. Many houses and their courtyards are enclosed by low stone walls, and during the agricultural season farmers construct temporary field huts near distant gardens.

Historically, Sikkanese agriculture depended almost entirely on shifting cultivation of dry fields. While these techniques persist in the eastern and western parts of the district, the introduction and spread of leguminous lamtoro (Leucaena spp.) has made possible more intensive cultivation of permanent, unirrigated fields, largely replacing shifting cultivation in the densely populated central region. The principal subsistence crops are rice, maize, and cassava, supplemented by millet, sorghum, and sweet potato. Only coastal villages have regular access to offshore fishing to complement agriculture, and commercial fishing—now a growing industry—is dominated largely by Butonese, Makassarese, and Chinese entrepreneurs. The traditional economy of central Sikka was profoundly altered in the early twentieth century by Dutch-encouraged coconut planting and the sale of copra. Extensive clearing of native forests for coconut plantations, combined with poor management, led to serious degradation of soil and water resources. More recently, government programs have promoted small-scale cattle herding in parts of the northern coastal zone.

Domestic animals commonly kept include dogs, cats, pigs, goats, ducks, chickens, and horses. Property rights encompass land, trees, houses, livestock, elephant tusks, gold, silver, ceremonial cloth, and old weapons. The household is the principal unit of land ownership, while residual rights over unclaimed land have traditionally been vested in either the “lord of the earth” (tana pu’ang) or the raja.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026