SASAK

The Sasak are the dominant group living on Lombok. An Austronesian people, they were Hindus before they converted to Islam beginning in the 16th century. Feuding between Sasak princedoms allowed the Balinese to dominate the island and reduce the Sasak to vassals and servants until the Dutch drove the Balinese out in 1894 and the Balinese ruling family committed ritual suicide. The Sasak language is similar to Balinese and Javanese. Related Austronesian peoples include the Bayanese, Balinese, Bali Aga, Sumbawa people, · Dompuan, Bimanese and Javanese. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

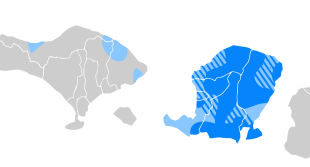

The Sasak (pronunced SAH-sahk) are also known as the Sasaknese. They number around 3.6 million and make up 85 percent of Lombok's population (the rest being mostly Balinese in the far west) and 68 percent of West Nusa Tenggara's population. The Sasak are related to the Balinese in language and in ancestry, as well as to other ethnic groups on the neighboring island such as the Sumbawansm Bimanese Javanese, Malays, and Makassarese as well. The Bayan people are a distinct part of the Sasak people, and are the oldest group on Lombok.

The 2010 Indonesian census counted 3,173,127 Sasak, 3,033,631 in West Nusa Tenggara, 22,672 in Bali, 22,194 in East Kalimantan, 20,436 in Central Sulawesi, 11,878 in South Kalimantan and 11,335 in South Sulawesi. The Sasak population in 2000 was 2.6 million. Overpopulation and rural poverty have made Lombok a source of transmigrants. Sasak transmigrants can be found in Sulawesi, and Sumbawa received its first Sasak transmigrants in 1930. In 2006, the Indonesian government registered a total of 32,835 Lombok residents working abroad. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Wikipedia]

The Sasak are divided into two groups: 1) the Wetu Telu, the more traditionalist Sasak, and the 2) Waktu Lima, the more conservatively Islamic and market-oriented Sasak. There has traditionally been some friction between the two groups over their beliefs and power. The Waktu Lima held higher positions under the Dutch and some have accused the Wetu Tela of being infidels. The Wetu Tela regard themselves as Muslims but have many radical beliefs. They do not build mosques, pray five times, go on pilgrimages to Mecca and have no objection to eating pork. In the Sasak language Wetu means “result” and telu means “three.” The number “three” looms large in their belief system. They fast for only three days during Ramadan and recognize the trilogy of the sun, moon and stars and the head, body and limbs The Wetu Tela have been declining in numbers and now mostly persist in remote areas. Their number are believed to be less than 30,000. ~

RELATED ARTICLES:

LOMBOK: HISTORY, PEOPLE, TOURISM, GETTING AROUND factsanddetails.com

MATARAM (LARGEST CITY IN LOMBOK): SIGHTS, TRANSPORT, THE SENGGIGI RESORT AREA factsanddetails.com

GILIS (ISLANDS) OFF LOMBOK factsanddetails.com

MT. RINJANI: HIKING, ACCOMODATION, CRATER LAKE factsanddetails.com

SOUTHERN LOMBOK: BEACHES, SURFING, DIVING AND A MASSIVE NEW RESORT factsanddetails.com

NUSA TENGGARA factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

Sasak History

Little is known about early Sasak history, aside from the fact that Lombok came under the direct rule of the Majapahit Empire by the fourteenth century during the tenure of the mahapatih Gajah Mada. Islam reached Lombok around the fifteenth century, and the Sasak population converted between the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. This process occurred largely under the influence of Pangeran Prapen (also known as Sunan Prapen), the son of Raden Paku (Sunan Giri), although some traditions attribute the conversion directly to Sunan Giri himself and to Muslim Makassarese missionaries. In many areas, Islamic teachings were blended with earlier Hindu-Buddhist beliefs, giving rise to the syncretic Wetu Telu religious tradition. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Wikipedia]

In the early sixteenth century, Lombok was conquered by the Balinese kingdom of Gelgel, resulting in the large-scale settlement of Balinese populations on the island. Today, Balinese number approximately 300,000 people, or about 10–15 percent of Lombok’s population, and their cultural and religious influence has been particularly significant in shaping Wetu Telu practices.

The Sasak refer to their island as Bumi Gora, meaning “Dry Farmland.” Another early name for Lombok is Selaparang, derived from the island’s earliest recorded kingdom, which was located on the eastern coast. In the early seventeenth century, Lombok became a contested territory between the Balinese kingdom of Karangasem and the Makassarese kingdom of Gowa, allied with the sultanate of Bima on neighboring Sumbawa. The Balinese ultimately prevailed, expelling the Makassarese in 1678 and completing the subjugation of Lombok by 1750.

While Sasak communities in western Lombok generally coexisted peacefully with the Balinese, sharing much ritual life despite religious differences, the Sasak aristocracy in the eastern regions strongly resented Balinese domination. In the nineteenth century, this resentment led to three major peasant revolts, conducted under the banner of orthodox Islam against what were perceived as “infidel” Balinese rulers. The final rebellion prompted intervention by the Dutch colonial state, culminating in 1894 with the mass suicide (puputan) of the Balinese Mataram court after fierce resistance.

See History Under LOMBOK: factsanddetails.com

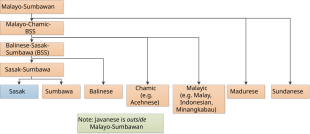

Sasak Language

The Sasak language (Base Sasaq) is an Austronesian language belonging to the Malayo-Sumbawan subgroup, which is part of the broader Western Indonesian (often termed Western Malayo-Polynesian) branch of Austronesian languages. It is spoken primarily on the island of Lombok in western Indonesia and is closely related to the languages of nearby regions, particularly Balinese and Sumbawan, as well as more distantly to Javanese and Sundanese. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Wikipedia]

Sasak is most closely related to the neighboring Balinese and Sumbawan languages. The language traditionally exhibits three caste-related speech levels, with Sanskrit-derived vocabulary especially prominent in the highest register. Arabic loanwords occur more frequently in the speech of orthodox Muslim communities, reflecting the influence of Islam.

Historically, Sasak was written in the jejawan script, derived from Javanese and nearly identical to the Balinese script. It has also been written using Arabic script and, increasingly in modern times, the Latin alphabet. Traditional texts were recorded on lontar palm leaves, though contemporary writing commonly uses factory-produced paper. Written materials include literary works, chronicles, administrative records, land grants, wills, and village regulations.

Sasak consists of several regional dialects. These include Kutó-Kuté and Bayan-Sasak in northern Lombok; Menó-Mené in central areas; Meriaq-Meriku in the central south; Ngenó-Ngené in central eastern and central western regions; and Nggetó-Nggeté in the northeast. In addition to Sasak, Indonesian is widely used, while Arabic is primarily restricted to religious contexts.

Sasak Religion and Islam

Most Sasak are Sunni Muslims who follow Wetu Lima (literally “Five Times”) Islam, referring to the observance of the five daily prayers required in orthodox Islam. This contrasts with Wetu Telu (“Three Times”) Islam— another religious belief found on Lombok — whose adherents perform prayers three times a day. Orthodox Islamic teachers generally promote five daily prayers as the correct practice. Sasak who continue to follow pre-Islamic belief systems are often referred to as Sasak Boda, a term derived from Bodha (or Boda), the name associated with the Sasak people’s original religion. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Wikipedia]

According to legend, Islam was introduced to Lombok from Java in the late fifteenth century by a Javanese holy figure, identified either as Sunan Giri or Pangeran Sangopati. Early Islam on Lombok appears to have been syncretic, a view supported by the fact that Pangeran Sangopati is also known in Bali as Pedanda Bau Rau, a priestly title. Over time, a clear division developed between syncretic practitioners who combined Islamic teachings with pre-Islamic beliefs and those who adhered more strictly to Islamic orthodoxy. The former became known as Wetu Telu Muslims, while the latter are called Wetu Lima Muslims.

The majority Wetu Lima Muslims adhere to Islamic orthodoxy, including the five daily prayers from which their designation is derived. For Wetu Lima adherents, moral behavior centers on avoiding sinful acts (haram) that would be punished in the afterlife, whereas Wetu Telu practitioners focus on avoiding the violation of taboos believed to bring misfortune in this life. Since Indonesian independence, the Islamic organization Nahdlatul Wathan has played an active role in efforts to reduce Wetu Telu practices.

Wetu Telu religious practice emphasizes the veneration of ancestors and local spirits through village rituals and communal feasts. Adherents observe only three days of fasting during Ramadan, recognize three principal obligations—to God, to community elders, and to parents—and do not perform the hajj pilgrimage, although they bury their dead facing Mecca. Many believe Mount Rinjani to be the dwelling place of ancestors and the supreme being and undertake fasting there during the three nights of the full moon. Religious specialists include village priests who conduct rituals on behalf of the community and pemangku, male or female spirit mediums who serve as guardians of sacred sites.

Significant Wetu Telu communities remain throughout Lombok, particularly in Bayan, where the tradition originated, as well as in Mataram, Pujung, Sengkol, Rambitan, Sade, Tetebatu, Bumbung, Sembalun, Senaru, Loyok, and Pasugulan. Precise figures for the Wetu Telu population are difficult to determine, partly due to persecution during the political upheavals of 1965–1966. Estimates suggest they may account for as much as 30 percent of Lombok’s population, with strong concentrations in the mountainous northern regions.

Funerals: Death rituals involve the entire community. The rhythmic pounding of rice mortars announces a death and calls on villagers to contribute rice and labor for the funeral. Alongside standard Muslim funerary rites, Wetu Telu practices include placing trays of food and other offerings on the grave. Carved wooden objects—simple pieces for men and decorative combs for women—are also placed on the grave and later replaced after 1,000 days with stones and holy water. Special feasts are held at the graveside, and commemorative ceremonies take place 3, 7, 10, 40, and 100 days after death, often including Qur’anic recitations. Ancestors are ritually informed before all major ceremonies. After approximately ten years, the bones may be exhumed and reburied elsewhere, allowing the original grave to be reused.

Sasak Traditional Religion

Traditional Sasak belief systems include ancestor worship, life-cycle rituals, reverence for local spirits, and sacred sites. Many animist and Hindu elements have been incorporated into Sasak Islamic practice, even among those who consider themselves devout Muslims. Balinese Hindu concepts of social hierarchy also persist, reflected in the existence of noble and commoner classes, often living in separate neighborhoods. High-status men may marry women of lower rank, whereas high-status women traditionally may not marry downward.

Approximately 8,000 Sasak adhere to indigenous non-Islamic beliefs similar in some respects to those of Wetu Telu practitioners. This group, commonly known as Boda, has successfully obtained official recognition from the Indonesian government as a form of Buddhism. The Boda prefer identification as Buddhists rather than Hindus—unlike some other Indonesian animist groups—in order to distinguish themselves from the Hindu Balinese, despite having little in common with the Mahayana Buddhism practiced by Lombok’s small Chinese community.

Prior to the widespread adoption of Islam, Lombok was predominantly Hindu. The conquest of the island by the Balinese kingdom of Karangasem in the seventeenth century further reinforced Hindu influence, traces of which remain evident today. Numerous ancient Hindu pura, including Gunung Pengsong, Lingsar, Meru, and Suranadi, are still standing and continue to serve as important cultural and religious landmarks.

Even among Wetu Telu Muslims, belief in a wide array of supernatural beings is strong. These beings include village founders, past rulers, ancestral spirits, spiritual doubles (jim), and personified spirits of the forest, mountains, and water (samar and bakeq). Additionally, witches (selaq) are believed to exist, and balian can communicate with spirits and provide healing. Wetu Lima Muslims are also known to fear jim and bakeq. Illness can result from spirit possession, black magic, or breaking taboos. Mystical power is believed to reside in heirlooms, such as old weapons. ^

Sasak Society

Sasak kinship is bilateral, though greater emphasis is placed on the paternal line, particularly in matters of noble rank and the inheritance of offices. Many rights and obligations are derived from the wirang kadang, a kin group consisting of the paternal grandfather, father, paternal uncles, and paternal cousins. Houses are privately owned, but the land on which they stand belongs to the village as communal property. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Traditional Sasak society recognized three social strata. The aristocracy consisted of two ranks, raden and lalu, followed by commoners, known as bapa or buling. In pre-colonial times, a third category included serfs and slaves (jajar karang). Marriage was ideally endogamous within one’s caste and particularly discouraged across downward lines. Aristocratic status did not necessarily correspond to wealth, and noble families could be poor. In contrast, Wetu Telu villages were characterized by widespread land ownership and relatively equal distribution of material goods.

Village governance included a village head (pemekel or pemusungan), neighborhood heads (keliang or jero), an irrigation official, a chief religious official (penghulu), a clerk, a village guard, messengers, and elders knowledgeable in adat (customary law). Social order was maintained primarily through traditional sanctions such as public reprimands by elders and ostracism. Collective labor was central to village life, with residents cooperating on communal tasks.

Sasak Social Relations

Respect for age and status is a fundamental feature of Sasak social relations. When greeting an elder, a younger person takes the elder’s right hand with both hands; children and younger relatives may kiss the hands of parents, uncles, and aunts. Disrespectful speech toward elders is believed to bring misfortune or calamity. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Courtship follows formal conventions. A young man wishing to meet a young woman traditionally visits her home under the supervision of her parents. He sits in the berugaq meeting pavilion or on the house veranda, speaking indirectly and often joining her in household or agricultural tasks. Communication may take place through a special courtship language or via an older woman acting as an intermediary. Customary law imposes heavy fines on a man and his family if he touches a woman in public view. Apart from the Bau Nyale festival, the harvest season was traditionally a key opportunity for young people to meet, when boys and girls approached each other in same-sex groups from opposite ends of the rice fields, singing and exchanging flirtatious verses.

Forms of address change with life events such as marriage or the birth of a first child. For example, a lower-ranking male aristocrat is addressed as Lalu before the birth of his first child and as Mami afterward. Elders and individuals of higher status are addressed as Side or Epe and spoken to in refined, respectful language—for instance, silaq medaran or silaq ngelor (“please eat”) rather than the more casual ke mangan. Younger siblings or cousins whose parents are younger than one’s own are addressed as Ante or Diq.

Sasak Family Life

The basic Sasak household unit is the nuclear family, sometimes expanded to include a widowed parent, a divorced child, or adopted children. Among aristocratic families, brothers and their households often continue to live together in a single compound after the death of their parents. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Life-cycle rituals are central to Sasak social and religious life, particularly among Wetu Telu communities. After a child’s birth, the father buries the placenta—believed to be the child’s spiritual twin and protector—in a designated sacred location. A priest formally names the child while scattering ash. Subsequent rites mark important developmental stages, including the first haircut at 105 days after birth, tooth filing, and, for girls, first ear-piercing, each accompanied by specific rituals and celebrations.

Circumcision is a major rite of passage for boys. Prior to the operation, the boy is dressed in elaborate ceremonial clothing and paraded on a wooden horse or lion adorned with palm-frond tails. No anesthetic is used, and the boy pays ritual respect to an unsheathed kris (short dagger). As major ceremonies are traditionally held after the harvest, circumcision celebrations often reuse chairs, glassware, and decorations from earlier wedding feasts. The festivities may also include ritualized, blood-drawing combat.

Inheritance practices vary by locality. In some villages, women are excluded from inheriting land, while in others they receive a smaller share than men, commonly at a ratio of one to three. Inherited property may include land, houses, and heirlooms such as cloth, jewelry, and kris. Jewelry is generally regarded as collective property shared among the women of a family.

Sasak Marriage and Weddings

Many marriages have traditionally taken place through elopement, which the Sasak refer to as “bride capture.” Marriages between cousins are common and often preferred but marriage is taboo between uncles and nieces or aunts and nephew. Within the limitations of caste there is considerable freedom in choosing spouses. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Wedding ceremonies vary in complexity, with more elaborate rituals observed among aristocrats and Wetu Telu communities. In formal weddings, the bride and groom are carried in sedan chairs, and the bride-price increases with the woman’s caste status. Traditional bride-wealth items include strings of old Chinese coins, ceremonial gilt-tipped lances, rice bowls filled with coins and covered with cloth and a small knife, as well as coconut milk and palm sugar. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Marriage by elopement is considered an economical alternative to a formal wedding. In such cases, the young man secretly takes the woman to another village, where he reports to the village head, receives 44 lashes as a symbolic punishment, and is required to wear a black string on his wrist as a public marker of the act. The village head then informs the woman’s family through their own headman. The groom subsequently sends a delegation to negotiate the bride-price, which is distributed among the bride’s relatives.

After marriage, couples may reside with either the bride’s or the groom’s family or establish an independent household, although aristocratic couples typically live with the husband’s family. Divorce is relatively common, with an average of three divorces per person over a lifetime. Among Wetu Lima families, children usually remain with the father after divorce, whereas among Wetu Telu families they may stay with either parent. One recognized means of divorce involves a wife returning to her parents’ home to signal dissatisfaction—often due to adultery or failure to provide. By refusing to communicate with her husband, she places social pressure on him and his family, frequently making divorce unavoidable.

Sasak Life

Villages range in size from several hundred people to more than 10,000. They are often set up around a mosque or mosques, or along a road and villages are generally arranged in a loose grid pattern and include a berugaq (community meeting hall), family dwellings, rice barns, one or more mosques or prayer houses, a cemetery, and sometimes a playing field. Larger villages are divided into neighborhoods (gubug), and aristocratic families may occupy separate residential compounds. Cidomo—hand- or horse-drawn carts used to transport both goods and passengers—remain a common feature on Lombok’s roads.[Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993); A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Traditional Houses are barn-like structures with bamboo frames, and thatched roofs, and are built on raised platform made of clay, dung and straw, or of packed earth. And enclosed by walls of bamboo or palm-leaf ribs and topped with a thatched roof. Each house typically includes an open veranda and two interior spaces: a lower room used for cooking and receiving guests, and an elevated room reserved for sleeping and storage. The distinctive lumbung rice barns, recognizable by their horseshoe-shaped profiles, have largely disappeared. Traditional houses have largely been replaced by concrete or wood houses with metal roofs.

Food: Rice forms the staple of the Sasak diet and is commonly supplemented with boiled cassava and sweet potatoes. The principal meals are lunch, eaten between noon and mid-afternoon, and dinner in the early evening. Breakfast, when affordable, typically consists of rice, maize, or boiled bananas accompanied by coffee. During the rainy season, fried maize with coffee is considered especially warming. Fruit is not a regular component of the rural diet, as it is more often sold in town markets. For Islamic festivals, special foods are prepared, including reket rasul, yellow glutinous rice served with chicken, and jaja tuja’, steamed glutinous rice cakes mixed with grated coconut. Berem, a fermented rice beverage, continues to be consumed among Wetu Telu communities.

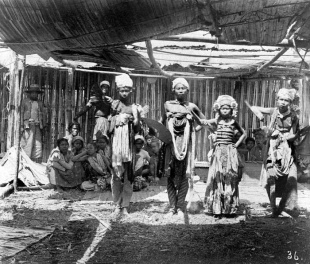

Clothing: In everyday life, Sasak men traditionally wear dark-colored batik sarongs, with the longer front edge held up while walking, paired with a white or gold-threaded breast cloth and a short-sleeved open shirt. Women wear a sarong secured with a waist sash and a black baju lambung, a wide-sleeved blouse cut short at the back. Older men and habitual smokers often carry containers for cigarettes and tobacco, while many women carry holders for betel-nut chewing. Ceremonial dress is more elaborate. Men add a sapu’, a batik headcloth marked by a white central stripe. Women wear a batik sarong, a long-sleeved kebaya, and a belt woven with gold thread. A kris dagger tucked into the belt commonly completes ceremonial attire.

Sasak Crafts and Sports

The Sasak are famous for their ikat textiles, basketry, and pottery. Women weave cloth and sleeping mats. Men make baskets, traps, containers made of animal hide, tools, painted house posts and doors and the wooden horses used as ceremonial mounts. Traditionally large wooden horses were made to carry celebrants during festivals.[Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993); A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

One traditional children’s game that remains widely played among the Sasak is bawi ketik (“kicking pig”). The game, which imitates a wild sow defending her piglets from hunters, is usually played during the day after daily chores are completed. One child, designated as the “pig,” kneels on all fours at the center of a circle and guards several stones placed beneath the body, each stone representing a “piglet” claimed by one of the “hunters.” Between five and eleven hunters attempt to retrieve their respective stones while the pig, remaining on all fours, may defend the piglets only by kicking at the hunters’ calves. Any hunter who is struck in the calf becomes the next pig. The game continues until all piglets have been taken. The hunters then hide their stones while the pig closes their eyes; the pig must search for the hidden piglets, and the owner of the first stone found becomes the next pig. Play continues until the children grow tired or lose interest.

Sasak men value physical strength. “Lanca”, a form of combat that originated in Sumbawa, and features men who strike each other with their knees, is also practiced. “Pereseban” is a form of recreational fighting and ritualized combat in which combatants use rattan staves and small rectangular shields. Peresehan is performed during wedding celebrations and rain-making ceremonies. It begins with two men, dressed in turbans and sashes, staging a mock duel with rattan sticks and buffalo-hide shields to the accompaniment of a gamelan ensemble. The fighters then invite members of the audience to participate, carefully matching opponents of similar ability. Participation may be declined, but victory confers considerable prestige. These bouts can become intense and often draw blood.

Sasak Performing Arts

Sasak performing arts include shadow puppet plays, dances, dramas, Islamic songs and gamelan-style music. Indigenous performing traditions are actively promoted in designated “traditional” villages and through government tourism initiatives, but they are often discouraged in more “modern,” orthodox Muslim communities. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993); [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Music: Sasak gamelan orchestras closely resemble those of Bali, sharing similar musical scales as well as comparable performance attire. Processional gamelans, akin to the Balinese beleganjur, accompany many dances. The gamelan gong Sasak blends elements of the modern Balinese gong kebyar with the indigenous oncer ensemble, while the gamelan grantang consists of bamboo xylophones. Because bronze instruments are taboo in some Islamic contexts—where they are associated with ancestral voices in pre-Islamic belief—alternative ensembles using iron instruments have developed, as well as rebana ensembles of Middle Eastern flat drums capable of performing gamelan repertoire.

Sung Poetry in different forms is a reasonably popular artform. These include cepuk, a recited and sung version of the Panji legends accompanied by suling flute, rebab fiddle, and a chorus that imitates gamelan sounds; tembang Sasak and Malay hikayat verse, the latter often translated simultaneously into Sasak; and recitations of the Barzanji, recounting the lives of the Prophet Muhammad and Islamic saints in a call-and-response format. Popular Sasak poetry is also performed with cilokaq (or kecimol) ensembles featuring the piercing preret oboe, plucked lutes, and rebana drums. In addition, the Jew’s harp, typically played in duets, remains a popular instrument.

Dance traditions are equally diverse. The tari oncer features two drummers performing interlocking rhythms while striking dramatic poses. Batek baris combines imitation of a Dutch military parade with female telek dancers portraying kings, ministers, and soldiers. In barong tengkok, performers animate a mythical lion figure while playing kettle gongs. Pepakon is a trance dance intended to heal the sick, and gandrung involves a solo female dancer who invites men from the audience to join her.

Theatrical Arts include kemidi rudat, which dramatizes stories from The Thousand and One Nights and has experienced a revival despite opposition from orthodox Muslim groups; teater kayak, a genre of masked drama encompassing forms such as Cupak Grantang and kayak sando; and Wayang Sasak, a shadow puppet theater tradition introduced from the Javanese city of Cirebon in the seventeenth century.

Sasak Agriculture, Work and Economic Activity

The Sasak are primarily farmers who raise wet rice with water-buffalo-pulled plows in fields outside their villages. A lot of work is put into maintaining irrigation systems and their dikes and canals. Other crops are also produced. Men have traditionally done the plowing, field clearing and dike repair while women pounded the rice, fetched water and took care of the households. Sasaks sometimes eat ferns. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

Wet-rice is often rotated with soybeans. Tobacco is a major cash crop and export, alongside betel nut, cinnamon, chilies, coffee, and medicinal plants. In more recent years, production has expanded to include pepper, vanilla, cloves, pumice, pearls, carrageenan-producing algae, and sea cucumber. Although Lombok is an island, most fish consumed by the Sasak is obtained through trade, as they are not traditionally seafaring people. Supplementary foods such as fruit, honey, edible leaves, and bamboo shoots are gathered from the wild. Livestock raising includes chickens, ducks, and goats, while water buffalo are typically reserved for ceremonial feasts. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Economic life varies by religious community. Wetu Lima villages generally maintain formal marketplaces, and itinerant traders are predominantly Wetu Lima Muslims, as Wetu Telu communities traditionally view commerce with suspicion. In recent decades, the rapid growth of international tourism on Lombok has created new and previously unavailable employment opportunities.

Labor migration has also become an important economic strategy. In 2006, 32,835 people from Lombok were officially registered as working overseas. Malaysia hosted the largest number, with an overwhelmingly male workforce of 26,142 men compared to 690 women. In contrast, migration to the Middle East was dominated by women employed as domestic workers: 5,610 in Saudi Arabia, with only 84 men, and smaller numbers in Kuwait (108 women) and Jordan (55 women), where no men were recorded. South Korea showed a more balanced gender distribution, with 108 workers—64 men and 44 women—all originating from the city of Mataram.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025