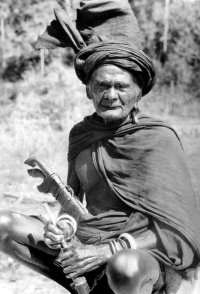

SUMBANESE

The Sumbanese are an Austronesian ethnic group that live on the island of Sumba in eastern Indonesia. Also known as Sumba or Sumbans, they are mostly a Malay people with some Melanesian blood and speak a language similar to that of the people on Flores. Although most are Christian traditional beliefs remain. The Sumbanese have unusual funeral customs and believe the first people of the world descended from heaven on a ladder and settled on the northern part of the island. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Administratively, Sumba island is divided into four regencies: Southwest Sumba, West Sumba, Central Sumba, and East Sumba. The Sumbanese refer to themselves as Tau Humba. Despite long-standing external influences that have reached the Lesser Sunda Islands, the Sumbanese have retained much of their traditional culture. Eastern Sumbanese have a distinctive culture shaped by the dry-season savanna and hilltop villages, as well as their long history of limited agricultural seasons. [Source: Joshua Project, Wikipedia]

Sumbanese are very diverse. Native Sumba languages include Kambera, Momboru, Anakalang, Wanukaka, Wejewa, Lamboya and Kodi. Bahasa Indonesian — the national language of Indonesia — is also spoken. The population of Sumba was estimated to be 853,428 in mid 2024, with 291,000 of these being Kambera-speaking East Sumbanese. The total population of Sumbanese was approximately 656,000 in 2008.

Jill Forshee wrote in “Culture and Customs of Indonesia”: In East Sumba, districts contain major villages of nobility and heads of large kinship lineages, which include clan households, important megalithic graves, and ritual centers. Despite more than five decades of belonging to a nation—with its national leaders, regional officials, modern institutions, and ostensibly democratic ideology—Sumbanese have steadfastedly maintained their caste and prestige systems. Usually at least four high-ranking families occupy major villages, frequently located on hilltops. Noted for its highpeaked ancestral clan houses (uma bokulu), Sumba remains a characteristically animist island, although there is much overlap between Christianity and the local Marapu faith. It was estimated in the mid-1990s that about one-half of the population still followed animist practices, and yet more if including Christian converts. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUMBA CULTURE: IKAT, CEREMONIAL CLOTHES, PASOLA HORSE FIGHTS factsanddetails.com

SUMBA: SIGHTS, TOURISM, VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

NUSA TENGGARA factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

Sumbanese Religion

Most Sumbanese are Christians. According to the Christian group Joshua Project 98 percent of Eastern Sumbanese are Christians. Of these 10 to 50 percent are Evangelicals. Christianity (both Protestant and Catholic) has grown steadily since the arrival of missionaries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In many communities, Christian affiliation coexists with traditional Marapu practices, resulting in a spectrum ranging from nominal syncretism to dedicated Christian faith. The Islamic presence on the island is comparatively limited. [Source: Joshua Project]]

The traditional Marapu religion, which includes ancestor veneration, spirit belief, and ritual practice, forms the backbone of Sumbanese cultural identity and serves as the philosophical core of Sumbanese culture. Marapu is expressed through clan rituals, megalithic tombs, ritual ceremonies, sacred houses (umaratu), traditional architecture, carved decorations, distinctive textiles such as hinggi and lau, traditional jewelry and weapons. and festivals intended to ensure fertility, prosperity, and social order.

Marapu is long-established system of ancestral worship practiced by the East Sumbanese. More than a religion, Marapu functions as a comprehensive moral and philosophical framework that guides social conduct, ritual practice, and relationships between humans, nature, and the spiritual realm. Marapu teachings emphasize values such as chastity, purity of the soul, harmony, peace, love, conformity, and balance—both between humans and the divine and between humanity and the natural environment. Through these principles, Marapu has long served as the foundation for ethical behavior and social order among the Sumbanese, shaping their worldview and daily life. [Source: Nicole Crowder, Washington Post December 19, 2014]

For centuries, horses have held a central place in Sumbanese culture and ritual life. Beyond their practical role as a means of transportation, horses are essential in ceremonial exchanges, serving as bridewealth, ritual gifts, sacrificial offerings, and symbolic vehicles for ancestral spirits. One of the most dramatic expressions of Marapu belief is the pre-harvest fertility ritual known as Pasola, a traditional mounted combat involving hundreds of horsemen throwing wooden spears at one another. Pasola marks the beginning of the agricultural season and coincides with the appearance of nyale—sea worms that emerge along the shore and are interpreted as a sacred sign of fertility and renewal. The ritual also serves as an expression of gratitude for anticipated abundance. Injuries are common during Pasola, and the spilling of blood onto the ground is traditionally regarded as a potent sign of ritual success.

Despite increasing modernization and the widespread adoption of global religions—particularly Christianity, which is practiced by approximately two-thirds of the island’s population—many Sumbanese continue to observe Marapu rituals. These practices persist alongside formal religious affiliations, reflecting a deeply rooted belief that ancestral spirits remain active protectors of the living. According to Marapu cosmology, the dead do not cease to exist but transition from the visible world into an ancestral realm, from which they continue to influence human affairs.

Marapu rituals are embedded in all major life events, including house construction, agricultural cycles, and funerary ceremonies. The building of a traditional house involves a series of rites intended to ensure spiritual protection and communal harmony. Offerings such as chicken feet and water-filled bamboo are placed at the construction site, while ritual specialists known as rato perform divination by reading signs in sacrificed animals. During roofing ceremonies, men climb tall bamboo poles in rituals symbolizing endurance and continuity of life.

Funerary rites are among the most elaborate Marapu ceremonies. They often include the pulling of massive stone slabs in a communal ritual known as tarik batu, in which men and women work together to transport megaliths used for tomb construction. Horses and other animals are sacrificed as offerings to accompany the deceased into the afterlife. These ceremonies are marked by public expressions of grief and reinforce social bonds, ancestral obligations, and the continuity of lineage.

Sumbanese Origins and Mythology

The exact period when Sumba Island was first settled is unknown. Earlier theories suggested that the island’s earliest inhabitants were Australoid peoples who later assimilated with incoming Austronesian populations, a view based largely on the presence of certain physical traits among the Sumbanese. However, more recent genetic studies indicate that while the people of Sumba are distinct from other Austronesian populations, the so-called Australoid features may have been acquired by their ancestors during migration rather than originating from an indigenous Australoid population.

According to Sumbanese oral tradition, the people of Sumba share genealogical ties with the inhabitants of neighboring Sawu Island. Origin myths trace both groups to two ancestral figures, Hawu Meha and Humba Meha. Hawu Meha is said to have given rise to the Sawunese, who initially lived on Sumba before migrating to Sawu Island. The descendants of Humba Meha remained on Sumba, becoming the ancestors of the present-day Sumbanese.

According to Marapu origin mythology, the first humans descended from the sky via a celestial staircase located in the northern part of the island. Genetic research aligns in part with this tradition, suggesting that the earliest settlements were concentrated along Sumba’s northern coast before spreading throughout the island. From the late Neolithic period onward, Sumba developed a strong tradition of megalithic construction, a practice that persisted remarkably into the twentieth century.

Sumbanese History

Sumbanese began interacting with outsiders centuries ago through trade, including the trade of sandalwood. During the medieval period, Sumba participated in regional trade networks, exporting valuable hardwoods and aromatic resins. Contact with Arab merchants introduced new horse breeds, and the island’s dry tropical savanna climate proved favorable to horse breeding, which became an important economic and cultural feature. Sumba is thought to have been loosely linked to the Javanese Majapahit kingdom and later to political networks involving Sumbawa and Sulawesi. In practice, however, authority was fragmented among local rulers engaged in ongoing power struggles, a situation that fostered the development of slavery.

Interaction with outsiders intensified with the Dutch colonial presence and Christian mission work in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1866, Sumba was incorporated into the colonial domain of the Dutch East India Company. Dutch influence was stronger in eastern Sumba, while the western regions retained more traditional ways of life. Following an uprising in 1901, the colonial administration introduced reforms aimed at economic modernization and the establishment of centralized governance. In 1949, Sumba became part of the newly independent Republic of Indonesia.

Christianity began to spread on Sumba in the nineteenth century following the arrival of European missionaries. Today, the majority of Christians on the island are Protestants, although Marapu beliefs and practices continue to coexist alongside Christianity and remain central to Sumbanese identity.

Sumbanese Funeral Customs

The Sumbanese describe the spiritual world with the word “maraapu” and regard death as an initiation into this world. As is true with the Toraja, the Sumbanese store deceased relatives for several years in a special death house before they are buried. The Sumbanese wrap the dead in blankets. The death houses are usually identified by a big set of water buffalo horns or the severed head of the deceased's favorite horse. In the past the an entire stable of horse might be sacrificed. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Sumba is also famous for its megalithic tombs, composed of four stone pillars, on top of which are decorated stone slabs. Many Sumbanese villages are built around huge carved granite megaliths that cover the graves where important nobles were buried with sacrificed slaves and horses. The tombs look like ornamented stone roof supporteds by columns. The granite used to make them was transported on rollers from sacred quarries miles away by hundreds of laborers drunk on palm wine. Technological shortcuts have been greeted with scorn. The best tombs are in western Sumba. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York,♢]

Describing a visit to a death house, Lawrence Blair wrote: "A few yards from the main, high-roofed place was a low building from which issued a chorus of gut wrenching wails...Inside I discerned a triangular-shaped bundle, about four feet high draped with royal ikat. This was solemnly introduced to us as the late Raja Pau. His body was squatting upright—in Sumbanese burial pose—with his elbows on his knees and his palms on his cheeks—beneath not one, but dozens of ikats...The Raja's brother than introduced us to yet more ikated bundles...There was his mother, father, brother, wife and sister-in-law. Some had been waiting for more than 20 years." At the foot of each bundle were cups of tea and food which were ritually "fed" to the corpses everyday. ♢

When Raja Pau died a good friend of his on the other side of the island began bleeding profusely from a cut on his neck. It turned out, his relatives said, that the Raja died because doctors failed to sew him up properly after a throat operation and the his wound opened, causing him to bleed to death. ♢

Sumbanese Society

The Sumbanese have a caste system which divides people into royalty, commoners and slaves. Although the government has officially freed them, slaves still exists. They are not slaves as we think of them because they are not bought and sold. “Slavery” is best thought of as a station in life. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

Historically, eastern Sumba functioned as a hub of trade and external contact. By the second half of the A.D. second millennium, this region had developed a complex social structure, including high-ranking warriors and leaders who held the royal title of raja. In contrast, western Sumba was characterized by smaller tribal groups led by selected local chiefs. In both regions, the central social units were major tribal communities that occupied villages and controlled surrounding land and water resources. These communities were organized into small nuclear families and larger extended family groups, with kinship and inheritance traced strictly through the patrilineal line. [Source: Wikipedia]

In East Sumba Regency, the traditional social hierarchy—comprising nobles (maramba), priests (kabisu), and commoners (ata)—still exists, though it is no longer as rigidly observed as in the past and is no longer clearly reflected in everyday dress or physical appearance. Today, distinctions in attire mainly indicate social importance during ceremonial occasions such as traditional festivals, weddings, and funerals. For such events, newly made garments are worn, whereas older or more worn clothing is typically reserved for daily activities.

Sumba society has been shaped by drought. Regular seasonal droughts have encouraged the development of a diversified subsistence strategy in which farmers simultaneously cultivate a variety of crops, including rice, beans, tubers, maize, and other staples. Although harvests are often modest and not consistently abundant, they generally provide sufficient yields for subsistence. Dutch missionaries and colonial officials noted that periods of hunger frequently contributed to outbreaks of armed conflict.

Sumbanese Life

The Sumbanese subsist on rice, cassava, tubers and corn and locally grown fruits such as bananas, papayas and mangoes. They also raise livestock, including cattle, buffalo, goats, chickens, and the locally prized Sumba horses. The locally bred horses, though small, are notably hardy and are well known throughout other parts of Indonesia. In the 1970s, the Blair brother said the Sumbanese pamper and then eat their pet dogs. The Blair brothers said they ate dog more than anything else when they visited the island. "It tasted somewhere between rabbit and goat, but richer in protein than either, and tended to make one sweat while eating it.” they said. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York]

Most Sumbanese people earn a living through subsistence farming. Villages are often built on hills and surrounded by defensive thorn barriers. The iconic peaked clan houses (uma mbatangu) serve as both practical dwellings and sacred spaces. Traditional activities such as weaving ikat textiles, wood and stone carving, and ritual performances, including the pasola horse festival, remain important social and economic practices. Tourism focused on these traditions has increased in recent years. Seasonal droughts, limited infrastructure, and economic pressures influence migration and livelihoods across the island.

Betel nut is widely chewed. It is given as a present and a welcoming gesture. In the old days betel nut was an important element of peace treaties. Chewing betel nut for the first time is regarded as a symbol of reaching adulthood. The stalk of the betel nut is said to represent the male sex organ; the nut, female ovaries. Lime is symbolic of sperm. The dead are sent off to the afterlife with a traditional betel nut bag. If someone offers you betel nut and you turn them down that is a great insult.

Traditional Sumbanese Houses

Traditional Sumbanese houses are frame-built bamboo structures raised on poles, with high pointed roofs and walls made of woven mats. The thatched roofs have a complex design that protects inhabitants from rain and intense sunlight while also providing natural ventilation. .Some villages are built on hilltops surrounded by stone walls or dense thorny vegetation, a reminder of when clan warfare was common on the island. The upper portion of the high thatched roofs are used to store sacred objects and house spirits. In a traditional village the houses are built facing one another around a central square with spiritual stones and stone slab tombs in the center of the square. In the old days the heads of slain enemies were hung from the “dead tree’ in the square and houses were built on hills for defensive purposes. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Jill Forshee wrote in “Culture and Customs of Indonesia”: In Sumba and neighboring islands, the concepts of “hot” and “cool” represent spiritually menacing or safe environments. Common people of Sumba dwell in modest, single story houses with plaited palm leaf or cement walls, both types typical throughout Indonesia. These are conceptually “cool” without spiritual significance. Although grass roofs have historically sheltered homes across the archipelago, now many people use corrugated zinc or iron. Metal roofs, however, radiate heat into buildings and do not allow ventilation as does grass. These newer roofs result in much hotter homes and the sound of rain on metal becomes extreme. Nonetheless, such roofs are longer lasting, impermeable to rats and insects, and appeal to many as low maintenance. For a time, even some large clan homes underwent repair with metal roofs. These generally are falling out of favor, though, due to increased household heat, an unaesthetic rusty appearance, and lack of customary value. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Noble clan heads bear the utmost responsibility for house maintenance. Throughout Indonesia, roofs in particular but also floors or entire structures need replacement about every 10 years. This obligation also falls to the people regarding the clan home as the basis of their lineage, even if they live far from “1it. As on other islands, descendants working in distant regions typically remit money to their families in Sumba in support of keeping a clan house standing. This also perpetuates the contributors’ inherent identities and ongoing psychological well-being, perhaps all the more needed if they reside at great distance from “home.” In fact, nobles may play upon their ranks while living abroad, if to their advantage. Such posturing carries a doubled importance, as conspicuous social status crucially concerns elite Sumbanese, wherever they are. Following a revival in prestige of older status symbols, some clan homes have been rebuilt grander than ever.

Spirituality of Traditional Sumbanese Houses

Jill Forshee wrote in “Culture and Customs of Indonesia”: In Sumba, people believe that ancestral spirits periodically inhabit spaces under roofs and critically observe their descendents below and inhabitants seldom risk improper behavior below the eccentrically high-peaked roofs. Propriety especially applies to sexual trysts. Extramarital or pre-marital sexual activity usually occurs in socially neutral and spiritually unsanctified spaces. These are simple, isolated garden huts, or even in the midst of high fields of maize, as those involved would feel shame and even fear in their visibility to ancestors. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Four ritual posts support the tall peaks (tiku) of roofs, which contain offering places for ancestors, family valuables, and male and femaleancestral figures. These pinnacles also periodically host spirits of ancestors during ritual events. Sitting on floors beneath roof peaks, skilled speakers employ sacred ritual language (spoken in poetic, paired couplets), calling Marapu spirits down to hear needs or witness important ceremonies of the living. Sumbanese perceive some clan homes as so forbiddingly potent with ancestral powers and life force (ndewa) that they fear living in them. A low caste person then often becomes the sole caretaker.

In Eastern Sumba, distinctions between “trunk” and “tip” shape a dynamic polarity in thought for a number of things, including households and lineages. While relative to concepts of “center” and “periphery” or “inner” and “outer,” the trunk and tip notions also coordinate with values of time depth. Thus, a trunk or old, established clan home holds eminence through its age. During construction, the four sacred posts supporting a Sumbanese roof peak become erected in a fixed order in a “movement to the right,” with each bearing a specific function. The first pillar to be set is at the right front, the site for divination. Here priests interpret signs through the organs of chickens and pigs, then offer the animals to the ancestors. The post conducts information between two realms.

Clan houses and the grounds surrounding them at times become hot and must be cooled by rituals, usually involving the blood of sacrificed animals. In a real sense “hot” implies forces of nature and the supernatural while “cool” relates to local culture and the human realm. The living must make their environments safe (or cool) by ritually appeasing the spirits and the dead. Opposing concepts (such as hot/cool, male/female, bitter/sweet, dark/ light) categorize and organize parts of a house. The masculine, right side of a house remains reserved for the rituals and public matters of men. Women’s domains occupy the left portion of a house, which include a bedroom, weaving areas, and often spaces behind the home.

A clan house roots a cosmological center for its members, providing a shared physical building and genealogical identity for a social group (even if uninhabited), while signifying “the starting point for each individual’s location in time.”40 The term for Sumba’s animist faith, Marapu, signifies ancestral roots. In a highly stratified society of three distinct castes (similar to Torajans), the clan house is one way in which “hierarchy and equality are created, imagined and maintained by reference to ideas of origin and ancestry as a ‘founding’ ideology.”

Sumba Megalithic Tombs

Megalithic tombs on the coast of Sumba were first built by islanders in the eighteenth century. Lavish ritual celebrations linked to the creation of megalithic tombs continue to draw the focus of archaeologists who seek to understand the role megaliths played in the lives of people who lived thousands of years ago.

Jill Forshee wrote in “Culture and Customs of Indonesia”:In eastern Sumba, the ground must be cooled with the blood of a sacrificed horse before a body can be carried safe from evil spirits to the grave chamber. In the west of the island, people sacrifice water buffalo for this purpose. In recent times, stone dragging carries renewed prestige, leading one anthropologist to note a “‘ritual inflation’ in the size, decoration and elaboration of new funerary art forms”68 in Sumba. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

People will drag a stone for distances as great as five miles over hilly terrain. This sometimes involves floating a slab across an ocean inlet atop logs for part of the distance. Sumbanese invest immense amounts of time and expense into funeral markers and their surrounding rituals. These continue to persist and evolve in grandness of scale and elaboration. In parts of Indonesia, graves consist of simple concrete slabs embedded with relatively cheap commercial blue or white square tiles. These permit comparatively inexpensive undertakings for the less affluent and often sit just outside of households. Yet, however humble a grave might be, it will bear indispensable value to those burying their dead.

Megaliths and Feasts on Sumba

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: On Sumba, archaeologist Ron Adams of Willamette Cultural Resources has studied how people conduct a ceremony known as tarik batu, or “pulling the rock.” This ritual involves acquiring stones from local quarries and dragging them to cemeteries where they are used to construct mortuary megaliths. He says islanders who have the means save for their entire lives to pay for monumental tombs built during what anthropologists call feasts of merit. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2024]

During these multiday festivals, as many as 1,000 people from related clans gather to haul stones weighing several tons. They also enjoy music, dancing, and feasts, all underwritten by the family or even a single individual who wishes to honor a relative or themselves. “Many of these tombs are built during the occupant’s lifetime,” says Adams. “It’s the fulfillment of a life’s dream for many.” He has observed feasts that involved slaughtering 100 pigs and 10 water buffalo—a considerable expense—during the construction of some the largest tombs on Sumba.

Archaeologist Tara Steimer-Herbet of the University of Geneva, who has excavated megalithic sites in the Near East for many years, has also observed tarik batu on Sumba. She says experiencing the songs and dancing and seeing expensive textiles draped over stones during the ritual led her to think differently about the prehistoric structures she has studied throughout her career. “They aren’t just these mute monuments,” says Steimer-Herbet. “They were erected during what must have been massive parties that were meaningful not just for the people who participated in them, but also for their descendants.” Just as they do on Sumatra and Sumba today, prehistoric megalithic monuments in the Near East and across the ancient world likely reminded people of the ancestors they honored and the rituals surrounding their construction.

For he most part the people of Sumba continue to build megalithic structures, but elaborate and expensive ceremonies for the dead have been abandoned.

Weyewa

The Weyewa inhabit the western highlands of Sumba and Nusa Tenggara Timur Province, where they cultivate rice, corn, and cassava using both slash-and-burn methods and continuous irrigation of paddy fields. They supplement this income through the sale of livestock, coffee, vanilla, cloves, and their distinctive brightly colored textiles. There were few challenges to Weyewa notions of political and religious identity until the 1970s. Because Sumba is a rather dry and infertile island, located away from the ports of call of the spice trade, it was comparatively insulated from the Hindu-Buddhist, Muslim, and later Dutch influences, each of which helped shape the character of Indonesia’s cultures. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Each Weyewa belongs to a kabizu, a patrilineal clan whose founding ancestors are spirits requiring frequent ritual propitiation, gifts, and respect in exchange for continued prosperity among the descendants. Each clan is headquartered in a fortified hilltop wanno kalada (ancestral village); the most traditional villages are characterized by houses with spectacular high-pointed thatch roofs. Young people are supposed to seek spouses outside their clan, and clan members assist with the often substantial marriage payments that are required. *

The Weyewa system of ritual production and exchange began to undergo major technological development and an economic shift in the 1970s and 1980s that resulted in a gradual weakening of the authority of lineages. With greater amounts of arable land available as a result of improved irrigation techniques and more crops produced because of the use of faster-growing and higher-yielding varieties of rice, the legal and cultural rights to these new resources came to be assigned to individuals rather than to clans. Younger farmers were increasingly reluctant to invest in costly, large-scale ritual feasts honoring the spirits. Meanwhile, government officials put further pressure on traditional leaders to give up ritual feasting practices as “wasteful” and “backward.” Furthermore, as with the Kaharingan adherents of Kalimantan, failure to affiliate with an approved religion was regarded as potentially treasonous. *

Unlike the Toraja and others, however, the Weyewa were not politically organized for the preservation of their indigenous religion. Most people simply converted to Christianity as a symbolic gesture of participation in the nation-state. Indeed, whole villages in the late 1980s and early 1990s conducted feasts in which residents settled their debts with ancestral spirits and became Christians. The number of Weyewa professing affiliation with the Christian religion (either Roman Catholic or Calvinist Protestant) jumped from approximately 20 percent in 1978 to more than 90 percent in 2005.

Sumba did not escape violence during the post-Suharto reform period, but the rioting took on distinctive forms. Because the central government was generally perceived in eastern Indonesia as a bountiful—if inequitable—source of funds for education, development, and jobs, the collapse of central authority resulted in open disputes. In November 1998, conflict broke out along ethnic lines as Weyewa men sought to defend the reputation of an ethnic Weyewa government official accused of corruption. The ensuing riots left at least 20 people dead and more than 600 homes destroyed. The public performance of peace rituals in 1999 began a slow, painful process of rebuilding trust between aggrieved parties. *

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025