SUMBANESE CULTURE

The Sumbanese people possess a rich and diverse oral tradition, expressed through well-preserved festivals and rituals, including horse races, bull sacrifices, elaborate funerary ceremonies, and ritual spear fighting. Traditional crafts include weaving and stone carving. [Source: Wikipedia]

Sumba is the home of the "sandalwood horse," a stocky, sure-footed animal that is so small tall Westerners drag their feet on the ground when they ride it. Originally brought to Indonesia by Arab traders, these horses were favored by the British Raj in India and South Africa because of their stamina in hot and humid climates and their resistance to tropical diseases. Westerners who ride sandalwood horses find that the horses sometimes bite their feet. The horse are ridden without saddles or stirrups. Other animals on the island include tropical birds, water buffalo, Brahmin cows and black swayback pigs. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993)]

In the past white nassa shells and glass beads were much desired and used like money by the Sumbanese. During the nineteenth century there was a flourishing trade with the Dutch, who prized Sumba’s sturdy horses for their cavalry and exchanged large quantities of shells and beads for horses with the ruling families of Sumba. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUMBANESE: LIFE, RELIGION, TRADITIONAL HOUSES factsanddetails.com

SUMBA: SIGHTS, TOURISM, VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

NUSA TENGGARA factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

Sumbanese Ikat Dying

Sumba is famous for its ikats (textiles made using an Indonesian decorative technique in which warp or weft threads, or both, are tie-dyed before weaving). They are sometimes embroidered with cowry shells and woven with mystical figures and "power shapes" that have secretive magical meanings specific to certain clans and kingdoms. The blankets are made of fine clothe woven from with fabric naturally dyed with indigo and red marinda from “kombu” tree bark. In recent decades these have been replaced with chemical dyes. In the old days ikat was only used for special purposes. Some were used in social planting ceremonies. Other could only be worn by royalty. Common ikat motifs include snakes, crocodiles (representing birth), "skull trees" (formally used to hang the heads of defeated enemies to scare off evil spirits), horses, dogs, buffalos, monkeys, lizards and warriors. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The island of Sumba in Indonesia is renowned for its technically accomplished and visually dramatic textiles. Sumba textiles tend in general to be syncretic and heavily indebted to imported imagery. Early trade and interaction amongst the Southeast Asian island archipelagoes meant that small islands close to trade routes were extremely vulnerable to commercial and political manipulation. Nevertheless a few outlying islands such as Sumba which had relatively homogeneous populations and scant economic potential in the eyes of trading Europeans, retained their cultural integrity while still enjoying expansive interrelations with their neighbors. Skillfully interpreting geometric pattern, Sumba weavers were able to preserve trade patterns that were introduced in a Hindu-Buddhist context more than a thousand years prior and innovate. These textile allows us to highlight important narratives pertaining to global trade, encounter and dynamic innovation in the arts of this region. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Dyeing was a secret and powerful art, known only to older women who practiced the supernaturally charged process in a secluded hut outside the village." A year was often required for the complex sequence of tying, dyeing, and weaving necessary to create a complex polychrome hinggi described below...Bold rows of frontal human figures, called tau or manuhia, adorn the ends. They probably represent male ancestors, and their ribs and other internal features are shown in a manner similar to that of the beaded ancestor images seen in other works. The trident-shaped motifs that flank the central panel depict andung (skull trees)-trees that in former times were cut down, stripped of their bark, and erected in front of the house of the village leader for the display of enemy heads, whose supernatural powers sustained the fertility of the community. Although warfare and head-hunting were banned by Dutch colonial authorities in the first decade of the twentieth century, the andung motif is still widely employed by contemporary Sum ban weavers. The larger design elements are separated by rows of chickens (manu). Important sacrificial anima ls, chickens were also used in divination and often symbolized the protective power of the ancestors. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

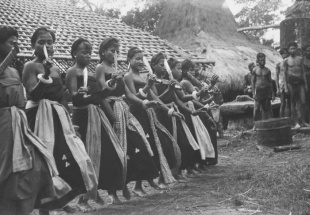

Traditional Sumbanese Clothing and Adornment

Sumbanese men have traditionally worn scarves as turbans, hitched up their sarongs so that much of their legs are exposed and wore a piece of cloth over that along with a long-blade knife in a wooden sheath in their waist belt. Women traditionally had their legs tattooed after giving birth to their first child. In some places women still go bare-breasted. Teeth filling used to be practiced but now is rarely seen except among very old people. Statues are an important element of spiritual life in Sumba. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Historically, the principal form of dress among the Sumba people was the ornamented ikat sarong, worn by both men and women to cover the lower part of the body. The most significant elements of traditional attire are large woven textiles used as body coverings: hinggi cloth for men and lau cloth for women. Produced through intricate weaving techniques and embellished with motifs such as muti and hada, these textiles convey a wide range of social, economic, and symbolic meanings. [Source: Wikipedia]

The attire of adult Sumbanese is generally determined by the level of importance of an event and the social context in which it occurs, rather than by rigid hierarchical status. Nonetheless, subtle distinctions remain. For instance, aristocrats typically wear garments made from finer cloth and more elaborate accessories than commoners, although the overall components and appearance are similar. Consequently, studies of Sumba men’s clothing tend to focus on traditional attire worn during major ceremonies, festivals, and public rituals, when men present themselves in their most formal and elaborate dress. Men’s attire consists of headgear, body coverings, and various accessories, including bladed weapons.

Men’s Clothing: For body coverings, men wear two pieces of hinggi cloth: hinggi kombu and hinggi kaworu. Hinggi kombu is wrapped around the hips and secured with a wide leather belt, while hinggi kaworu—also known as hinggi raukadama—serves as a complementary cloth. The head is adorned with a tiara patang, a form of headgear tied with loops and knots that create a crest-like shape. This crest may be positioned at the front, left, or right side of the head, depending on the intended symbolic meaning; a crest placed at the front, for example, represents wisdom and independence. Both the hinggi and the tiara are produced using ikat and pahikung weaving techniques. Headgear made specifically with the pahikung technique is known as tiara pahudu.

A wide range of decorative motifs appears on the hinggi and tiara, particularly representations of living beings, including abstract human forms (such as skulls), prawns, chickens, snakes, dragons, crocodiles, horses, fish, turtles, squid, deer, birds, and buffalo. Other motifs reflect foreign influences, especially from Chinese and Dutch cultures, such as dragons, tricolor flags, crowns, and lions. Each motif carries symbolic meanings rooted in mythology, collective thought, and deep beliefs associated with the Marapu religion. Color also plays an important role, reflecting aesthetic values and social distinction. In terms of prestige, hinggi kombu is regarded as the finest cloth, followed by hinggi kaworu, hinggi raukadana, and finally hinggi panda paingu.

Men’s attire is further completed by a kabeala knife inserted on the left side of the belt, along with accessories such as the kanatar bracelet and mutisalak coral beads worn on the left wrist. Traditionally, footwear was not part of men’s attire, although shoes are now commonly worn, especially in urban areas. The kabeala symbolizes masculinity, while the mutisalak signifies economic capability and social standing. Together with other embellishments, these elements collectively represent ideals of wisdom, strength, and moral virtue. Heirloom objects, including the marangga neck circle-pectoral and gold jewelry known as madaka, are also worn during important ceremonies. Outside such occasions, these items are usually kept in the attic of the house, as they are believed to possess strong spiritual power.

Women’s Clothing: Festive and ceremonial women’s attire in eastern Sumba involves the selection of several textiles, named according to their weaving styles, such as lau kaworu, lau pahudu, lau mutikau, and pahudu kiku. Decorative fabrics are worn as a lower-body covering that may extend up to the chest (lau pahudu kiku), while the shoulders are covered with a matching cloth known as taba huku. Head adornments include plain-colored tiaras accompanied by hiduhai or hai kara ornaments. The forehead is decorated with metal jewelry—often gold or gilded—known as marangga, while the ears are adorned with mamuli ornaments. Golden necklaces are also worn, hanging down to the chest.[30] Just as men carry the kabeala, women traditionally carry the kahidi yutu knife when leaving the household or attending formal occasions.

Hinggi

Hinggis are large blanket-like shawls worn by Sumbanese men as shoulder or hip cloth and used to wrap the dead at traditional burials. The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a hinggi ( made of ikat-dyed cotton. Dating to the early 20th century, it measures 223.5×121.9 centimeters (88 inches high and 48 inches wide).Eric Kjellgren wrote: The colorful ikat textiles known as hinggi accompany Sumban men through this world and the next. Used exclusively by men, hinggi are prestige garments, which, like women 's Lau hada serve as formal attire at important events and ceremonies. Made in identical pairs, hinggi are worn in matched sets, one around the hips and a second around the shoulders. They also form an indispensable component of the ceremonial gifts exchanged at marriages and on other occasions to cement alliances between families. Their most dramatic role, however, comes after death, when hinggi serve to enshroud the deceased. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Large numbers of hinggi are needed for the taningu (funeral ceremonies) of prominent men. For the highest-ranking members of the maramba (nobility), taningu are staggeringly expensive, requiring the sacrifice of large numbers of water buffalo, horses, and, formerly, slaves, the accommodation of hundreds of guests, and the acquisition of vast quantities of hinggi and gold valuables, such as mamuli. In the past, as many as twenty years might elapse before the family could gather all the resources necessary for the ceremony. While awaiting burial the body was wrapped in scores of hinggi, which effectively mummified it. At the funeral the deceased was interred enshrouded, at times in more than a hundred hinggi, together with numerous gold ornaments inserted in between the layers of textiles. Hundreds of additional hinggi were distributed as gifts to the assembled guests.

According to oral tradition, all patterned textiles, known as hemba maramba, were originally a prerogative of noble families and their retainers. Although this restriction was relaxed in historical times, the colors and imagery of hinggi proclaimed the status of the wearer. Low-ranking men wore hinggi of blue and white. Nobles were entitled to use red as well as a deep blue-black. The highest aristocracy employed a fifth color, a golden brown, which was painted freehand on the completed textile.

As in many Indonesian textile traditions, the patterns of Sumban hinngi frequently represent a dramatic fusion of indigenous and foreign imagery. The gridlike geometric design that forms the central field is derived from the patterns of patola, silk trade cloths from the Gujarat region of India that were treasured heirlooms among noble families. On Sumba, the right to use certain patola patterns was restricted to specific aristocratic families, for whom the designs served much like a family crest. Some hinggi incorporate Dutch coats of arms, derived from coins, or dragons, inspired by images from Chinese porcelain. Apart from its central patola pattern, the present work reflects indigenous Sumban imagery.

Lau Hada

A lau hada is Sumbanese woman's ceremonial skirt. The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains one from Bolobokat, central Sumba made in the early 20th century from cotton, beads, nassa shells and measuring 157 5 x 49.5 centimeters (62 x 19.5 inches). Eric Kjellgren wrote: The ornate beaded skirts, or lau hada, of Sumba were prestigious ceremonial garments worn exclusively by aristocratic women. Symbols of wealth and power,lau hada were embellished with white nassa shells and glass beads, precious imported materials that also circulated as currency. enabling the creation of sumptuous lau hada. [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The skirts were woven by local women, who sewed together lengths of fabric to create a long tubular skirt into which the wearer stepped, pulling the garment upward around her body. The upper half of each skirt was undecorated, allowing it to be folded and adjusted to the desired length to show the beaded designs on the lower portion to their best advantage. Secured by a belt at the waist or shoulders, lau hada could be worn either as skirts or as full-length dresses.

Composed of hundreds of nassa shells and glass beads, the imposing male and female figures that adorn opposite sides of the Met’s work stand out boldly against the subtle brown earth tone of the surrounding fabric. Probably representing an ancestral couple, they are depicted in an otherworldly, X-ray style, the ribs accentuated with colored beads. At their waists the figures are flanked by enigmatic equestrian figures. Stylized lizards, creatures associated with fertility, appear below the sexual organs, as if to emphasize the procreative force of the ancestors, whose powers ensure the birth of succeeding generations.

Shadowy images of lizards or crocodiles (wuya), depicted in feathery tufted embroidery, which swayed with the wearer's movements, appear beside the shell-and-bead images. Associated with the nobility, crocodiles and other amphibious or aquatic species signified qualities such as bravery and cunning. Their dualistic nature as creatures of both land and water was also believed to enable them to move between the natural and supernatural worlds. As both festive attire and ceremonial gifts, lau hada formerly played a prominent role in the marriage ceremonies of the nobility (maramba). A noble bride wore a lau hada as she walked in ceremonial procession to the house of her husband 's family.

As elsewhere in eastern Indonesia, regardless of whether they are men's or women's garments, in Sumba textiles, which are produced exclusively by women, are considered symbolically "female." During marriage rites, textiles are ceremonially presented by the bride's family to the groom's, who present "male" objects, including weapons and gold ornaments such as mamuli in return." For this reason, lau hada are also called pakiri mbola (at the bottom of the basket), in reference to the correct placement of these prized textiles among the vast numbers of cloths presented as marriage gifts. After marriage, aristocratic women wear lau hada.

Mamuli

Distinctive Sumbanese ornaments known as mamuli play an essential role in the elaborate ceremonial gift exchanges practiced on important occasions. In the past, when the Sumbanese artificially elongated their earlobes, mamuli were worn as ear ornaments, but today they hang around the neck as pendants. The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains an ear ornament or pendant (Mamuli) from eastern Sumba island, Kanatangu district. Dated to the 19th century and made of gold, it measures eight centimeters (3.15 inches). Another one in the collection also dated to the 19th century and made of gold (9.5×11.4×1.9 centimeters (3.75 inches high, 4.5 inches wide and .75 inches deep.

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Gold ornaments play a central role in marapu, the indigenous religion of the island of Sumba, which still has many adherents today. In the elaborate ritual exchanges of gifts that accompany marriages, alliances, and other rites, gold jewelry and other metal objects such as weapons, considered symbolically male, are exchanged for the islands lavish textiles which are identified as female. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Perhaps the most important of all Sumban gold objects are the omega-shaped jewels known as mamuli. Created as prestige ornaments for the nobility (maramba), mamuli can be worn as ear ornaments or pendants, or they can be attached to jackets and headdresses, depending on regional custom and the requirements of the occasion. The one in the Met collection comes from East Sumba, where mamuli were worn by men. In marriage, mamuli, water buffalo, horses, and other "male" gifts are presented by the groom's family to the bride's, who reciprocate with "female" gifts of textiles and other objects. Although a "male" gift, the mamuli depict stylized female genitalia. When given at marriage, a mamuli symbolically substitutes for the bride, '·replacing the young woman's dark eyes as she leaves to join her husband 's family.

According to marapu belief, gold is ultimate! of celestial origin. The sun is made of gold, which it deposits in the earth at sunset. The great noble families acquired much of the gold required to create mamuli and other ornaments during the 19th and early 20th centuries from the Dutch colonial authorities, who traded gold coins and other valuables such as glass beads and nassa shells in exchange for the island 's small. sturdy horses. The makers of gold ornaments are often foreign as well. While some Sumban men practice metalworking, most jewelry is made by itinerant goldsmiths or immigrants from the neighboring islands or resident Chinese craftsmen. Some wealthy familiesvommission pieces from the distant master craftsmen in Bali, Java, or the city of Ujung Pandang (Makassar) on the island of Sulawesi.

The imager of the mamuli expresses Sumban tastes and aesthetics. Although the fundamental imagery of the mamuli is feminine, individual ornaments were considered either male or female depending on their secondary characteristics. Male mamuli, such as the one at the Met were accented with spirals of gold braid and equipped with elaborate flaring bases, or "feet" (ledu); female examples lacked these features. The feet of the finest examples are embellished with minute figures of humans, animals, or other subjects. The minute warriors on the feet of the the Met’s piece are ingeniously jointed, with movable heads and arms and feet that swivel on their bases, allowing the figures to be posed in a variety of attitudes. They wear turbanlike headdresses and brandish swords and shields, their martial prowess emphasized by the smaller figures accompanying them, who appear in attitudes of supplication.

Enormously costly and supernaturally powerful, elaborate mamuli such as this were sacred objects that were almost never used as ornaments or exchange valuables. Instead, they were considered tanggu marapu (possessions of the spirits), sacred heirloom treasures that embodied both materially and spiritually the wealth and prestige of noble families. Secreted in the treasury in the dark loft of the towering peaked roof of the clan house, tanggu marapu were seldom seen or handled. Some could be temporarily retrieved by religious specialists, who used the oldest mamuli and other heirlooms as intermediaries in communicating with ancestral spirits. Others were considered so powerful that they were almost never removed from the darkness of the treasury for fear that their supernatural "heat" (mbanoho) would kill those who gazed upon them or cause natural disasters.

Pasola

Sumba is perhaps best known for the annual Pasola festival, in which two teams with dozens of men run after each other full speed on horseback and hurl javelins at one another. Pasola is the most prominent cultural festival of the Sumba people and is regarded as one of Indonesia’s most distinctive and rare ritual traditions. It is most widely practiced in West Sumba Regency, where spectators travel long distances to witness the event. The festivals are held in wide lush green valleys and linked to the tradition of constructing monumental megalithic tombs. The exact dates are determined by shaman who disembowel live chickens and examine the entrails for omens after glowing worms burst forth in the sea.

Pasola has been performed for centuries and is closely associated with agricultural fertility, particularly the rice-growing cycle. Traditionally, the spilling of blood during Pasola was believed to ensure soil fertility and a prosperous harvest. The Pasoloa takes place over several weeks, typically between February and March, marking the transition from the rainy season to the planting period. Sometimes two or more festivals are held at different times of the year, depending on several factors including the involvement of the government and the tides. Typically there is an event in February in Lamboyo and one in March in Guara and Honokaka. The battle begins several days after the full moon and coincides with the arrival nyale — strange multicolored seaworms.

Pasola is deeply embedded in Sumbanese cosmology and Marapu belief systems. Participants and elders maintain that the ritual retains its spiritual potency and that misfortune may befall those who take part with impure intentions. The ritual is preceded by animal sacrifices and divination ceremonies, reinforcing its sacred character and communal significance. In recent decades, Pasola has attracted growing attention from domestic and international tourists, though visitor numbers remain relatively low compared to other Indonesian destinations. Local and provincial authorities have promoted the festival as a means of stimulating economic development on the island, which remains heavily dependent on subsistence agriculture and traditional crafts.[Source: Angela Dewanm AFP, April 2, 2014]

Pasola Horse Fights

The Pasola horse fights feature scores of colorfully-dressed horsemen battling each other in a very serious way. During the war ritual, two opposing groups of mounted warriors engage in ritual combat by charging and hurling spears at one another. Spectators are fair game and it not unusual for there to be at least one death during the event but the main objective has been to draw blood to satisfy the gods rather than kill people.

The horses used in the Pasola have bridles adorned with horse-hair ruffs, ribbons and bells. Some of the horses have their ears notched. No saddles are used. Some riders sit on pads others ride bareback. The Pasola takes place in a huge field about the size of ten football fields. Each team has about 70 riders. Each rider carries two weapons, blunt five-foot-long poles that resemble broomsticks. Warfare has traditionally been a key element of Sumbanese life. Sometimes the mock battles become real. In August 1992, two villages went to war. Several people were killed and 80 homes were burned.

Some scholars consider the festival to be "a veiled form of human sacrifice." In earlier times, Pasola functioned as a form of ritualized violence in which serious injury or death was considered an honorable outcome for participants. In the 1990s the government banned javelins with sharp points. Spears are now blunted and metal tips removed, and ritual animal sacrifice has largely replaced the spilling of human blood. Some people have argued that since the the spears have blunted more people have been killed by the blunt wooden spears that are aimed at the temple and neck. But overall, while injuries may still occur, deaths are now rare, and the event is overseen by local authorities to prevent uncontrolled violence. [Source: Angela Dewanm AFP, April 2, 2014]

Pasola Glow Worms

Before the Pasola horse fight there is a two-hour warm-up at the beach where “nyale” — glowing sea worms — appear. People look for nyale on beaches like the one near Wainyapu and Ratenggaro Village, Kodi District and sing to call them. Their appearance — and the catching of them — are viewed as signs to mark the start of the Pasola ritual,

Upon witnessing the arrival of the glow worms on the beach, Blair wrote: "'Nyale! Nyale! the crowd began shouting, as the first rosy glow of dawn began creeping across the sea. But as I looked close I realized the redness was more than the dawn—the seaworms were swarming, wriggling multitudes staining the beach with every wave. The high priest was the first to wander sedately into the surf to sample this "gift of the Sea Goddess's body,' and to announce its portents to the crowd...'If the worms are healthy and plentiful, it will be a good year,' he said. 'If they fall apart at the touch , then enough rain can be expected to rot the rice on its stem. And if they are pitted and damaged, then a plague of rats or insects is probable.'...As soon as the priest had given his verdict, the crowd rushed into the surf themselves to scoop up the seaworms in their cupped sarongs or woven baskets for a holy breakfast, which they quickly cooked over small driftwood fires and ate." [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York,♢]

Nyale are also central to Lombok's Bau Nyale Festival. They are bioluminescent, glowing in various colors (green, yellow, violet-blue) as they emerge from the sea, a phenomenon linked to folklore and local tradition, though the specific glow is usually from related bioluminescent marine worms in general.

The Nyale worms (Scientific name: Eunice viridis or Palola viridis) are also called palolo, Samoan palolo worms, balolo and wawo. They are Polychaeta worms most often found in waters around Pacific islands such as Samoa, Tonga, Fiji, Vanuatu as well as islands of Malaysia, Indonesia, East Timor and the Philippines. Palola worms are about 30 centimeters (12 inches) long. They use their strong mandible to excavate a burrow for themselves in the hard coral reef, eating polyps as they go. Inside their coral burrows they are safe from predators and seldom venture out. They spend most of their time with their heads, called atokes, inside their burrows. [Source: Erin McCarthy, Mental Floss, April 9, 2015; Wikipedia]

See Palolo Under WEIRD MARINE WORMS: PENIS FENCERS, PURPLE SOCKS AND TOXIC ONES 55 METERS LONG ioa.factsanddetails.com

Description of the Pasola Horse Fight

Describing the start of the Pasola, Blair wrote: " Suddenly the two high priests of the Upper and Lower Worlds broke their ranks and galloped their horses at full speed towards each other into the center of the field, waving their spears and invoking the energies they represented to come and join the battle. Then, with unexpected violence they hurled their javelins from a distance of about fifteen feet—intentionally missing each other by a hair's breadth. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York,♢]

"This was a signal for the battle to begin, and as they withdrew from center stage they were engulfed as the first thunderous onslaught of spearmen charged each other at the gallop, their vivid orange, red and green turbans and ribbons streaming in the air...waves of warriors ebbed and flowed around the field, occasionally charging straight into the ranks of the spectators, tossing their spears with abandon. ♢

"I saw a number of riders struck heavily off their mounts by spears, rolling into balls and being cantered over by scores of other horses. They then leapt to their feet and limped hurriedly off the field. Another man was knocked unconscious and carried off almost triumphantly, only to come to again...and shout angrily for his horse, mount it and charge into the fray once more...We saw one guy killed instantly. He was knocked off his horse by a blunt spear hitting him on the temple." ♢

F. Dennis Lessard wrote in International Travel News: "The action was hot and heavy. The riders coming from the left side often would use the crowds a shield, riding very close to us and then darting toward the center. Often these riders would be spotted and spears from the other side would come our way. Several times we had to duck or jump out of the way."

Tourists often get hurt. "A young boy very near to me," Lessard wrote, "got hit in the head and was bleeding. An Australian tourist got hit in the back and almost knocked out. I saw the big bruise on his back—he was really hurt. Just then it started to get out of hand. Some of the unmounted men who were retrieving spent spears started throwing them at riders and one side started throwing rocks." The police moved in to break things up and started firing shots in the air. They came my direction...and the crowd scattered across the creek."

Rajura Boxing

The Pasola is preceded by the “rajura”, a traditional all-night ceremony featuring boxing matches between men from rival districts. Describing a rajura boxing match held on beach accessible by an arduous seven mile walk, F. Dennis Lessard wrote in International Travel News: "The pradjura, like the pasola, is ritualized combat between rival districts that is required for the success of the yearly agricultural cycle, but it also serves as an outlet for pent-up aggression between groups who not too long ago were headhunters."

"Each group put forth its best men, about 10 to 12 on each side, standing about 15 feet apart. They and the crowd had been working themselves into a frenzy by yelling and jumping up and down. The fighters were allowed to wrap their hands and we saw one close up. He took a bunch of saw grass and held it on his fist with the sharp stubble sticking out. Then he twisted the grass and wrapped it 'round and 'round his hand until he could barely close his fist. The grass makes the fist a deadly weapon; it could cut flesh if a good blow were landed. The blood of the warriors helps to fertilize the ground for the new crops which are planted shortly after the pasola events take place. There are some preliminary prayers and talking and the ground rules were laid out (no rocks or pieces of metal)."

"The two lines of young men faced each other and when the signal was given they started feinting back and forth. Everyone was yelling. Suddenly one man would dart forward, take a swing at an opponent and try to run back without being hit. If a hit were scored or if things got out of hand they would stop and rest. There were 'refs' from a neutral village and they tried to keep tight control.

"The young men were barefoot and bare legged, most wearing shorts and a T-shirt and some wearing the wrapped loincloth and cloth head scarf. The “parangs” (fancy, long knives) that are usually carried by all the men were not allowed in this area...It was dark and there was no moon and no large fires; they discouraged flashlights as the light could blind the fighters. This went on for several hours...During the last session, one of the men from 'our side' got bloodied near the eyes and Ali thought they would really go at it. I saw a woman carrying two parangs and I saw other men putting them on and I thought, 'Oh-oh.' But that was the end, The fighting was over and they were allowed to wear their knives again.

"I think what stopped the fighting at the end was the discovery of the small sea worms in the water. Everyone rushed down to the shore to gather them. The worms are central to all of the pasola activities and their presence and appearance are supposed to tell the ratu if the pasola should be held; they also foretell the future for the coming year."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025