KOMODO ISLAND

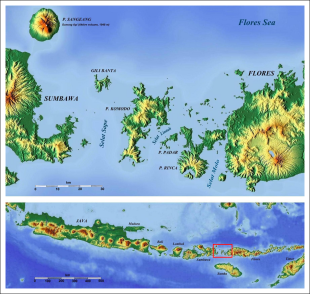

Komodo Island (east of Sumbawa and generally reached by boat from Flores) is the home of the famous Komodo Dragon, the world largest lizard, which can reach lengths of three meters including the tail, and wasn't even discovered by outsiders until 1912. Tourists used to come to see the dragons fed on a goat in a pit. The pit exists but dragons are no longer fed there. Some visitors skip Komodo altogether and look for dragons on Rinca island because it is easier to get to. Komodo Dragons also live on Rinca, Padar and western Flores. These volcanic islands are inhabited by a population of around 5,700 giant lizards. Komodo Dragons exist nowhere else in the world and are of great interest to scientists, especially for their evolutionary implications.

About 30 kilometers long, Komodo is comprised mostly of grassy hills, steep mountains and dry savannahs. The forests are filled with tamarind and kapok trees. The dry savannah feature Lonar Palms, and stunted Sujube trees. The rugged hillsides of dry savannah and pockets of thorny green vegetation contrast starkly with the brilliant white sandy beaches and the blue waters surging over coral. In 1928, Komodo was named a Wilderness Area, one of the first of its kind in Asia. Komodo National Park encompasses an area of 173,00 hectares, with three fourth of that on land and one fourth in the sea.

Other wildlife found on Komodo include Timor deer, wild pigs, an endemic rat, the orange-footed scrub fowl, the black-naped oriole, a helmeted friarbird, a Wallecean drongo, yellow-crested cockatoos, baseball-glove-size moths, hand-sized spiders (whose venom is a "little poisonous”), and ants that has been compared with "meaty little dumbbells."

Divers claim that the Komodo waters are one of the best diving sites in the world. The rich coral reefs and mangrove forests of Komodo host a great diversity of species, and the strong currents of the sea attract the presence of sea turtles, whales, dolphins and dugongs. There are 385 species of corals, 70 types of sponges and various types of sharks and stingrays.

Komodo Island definitely has an eery feel to it. The first afternoon we were there, my brother and I went looking for dragons: we didn't find any, but every time we heard a rustle in the bushes our hearts jumped. There are a lot of deer, wild pig and large birds on the island as well. The town of Komodo has several hundred residents. They live in ramshackle houses set up along dirt roads or by the sea. Women hang squids on lines. Children tend goats and chase crabs. Visitors stay in Loh Liang, a tourist camp run by the Directorate of Forest Protection and Nature Conservation (PHKA).

RELATED ARTICLES:

KOMODO: DIVING, ACCOMODATION, GETTING THERE factsanddetails.com

MANGGARAI: THE MAIN ETHNIC GROUP ON KOMODO factsanddetails.com

FLORES: VOLCANOS, SIGHTS, LABUAN BAJO factsanddetails.com

SUMBAWA: SIGHTS, BEACHES, TAMBORA factsanddetails.com

LOMBOK: HISTORY, PEOPLE, TOURISM, GETTING AROUND factsanddetails.com

NUSA TENGGARA factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF NUSA TENGARRA (ISLANDS EAST OF BALI) factsanddetails.com

Komodo National Park

Komodo National Park (between the islands of Sumbawa and Flores) is composed of three major islands (Rinca, Komodo, and Padar) and numerous smaller ones, all of them of volcanic origin. Located at the juncture of two continental plates, this national park constitutes the “shatter belt” within the Wallacea Biogeographical Region, between the Australian and Sunda ecosystems. The property is identified as a global conservation priority area, comprising unparalleled terrestrial and marine ecosystems and covers a total area of 219,322 ha. The dry climate has triggered specific evolutionary adaptation within the terrestrial flora that range from open grass-woodland savanna to tropical deciduous (monsoon) forest and quasi cloud forest. The rugged hillsides and dry vegetation highly contrast with the sandy beaches and the blue coral-rich waters. [Source: UNESCO]

The park was established in part to protect the Komodo dragon, which is found only on the islands in or near the park and is officially classified as vulnerable. Because of the unique and rare nature of this animal, Komodo Nation Park (KNP) was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1986. There has also been an effort to include it on a list of the New Seven Wonders of Nature. The park’s three major islands—Komodo, Rinca and Padar—and numerous smaller islands together total about 603 square kilometers of land. The total size of Komodo National Park, with sea areas included, is presently 1,817 square kilometers. Proposed extensions of 25 square kilometers of land (Banta Island) and 479 square kilometers of marine waters would bring the total surface area up to 2,321 square kilometers.

It is thought that the islands have long been settled due to their strategic importance and the existence of sheltered anchorages and supplies of fresh water on Komodo and Rinca. The evidence of early settlement is further supported by the recent discovery of Neolithic graves, artefacts and megaliths on Komodo Island.

For more information please contact:

Komodo Marine National Park Office, Jl. Kasimo Labuan Bajo

West Flores, East Nusa Tenggara 86445

Ph. +62 385 41004, fax: +62 385 41006

e-mail: tnkomodo@indosat.org

www.komodonationalpark.org

PT Putri Naga Komodo

Bali Branch, Jl. Pengembak No.2 Sanur 80228, Bali

T: +62 381 780 2408

F: +62 361 747 4398

e-mail: info@putrikomodo.com

www.gokomodo.org

Labuan Bajo

Gg.Masjid, Kampung Cempa. Labuan Bajo, 86554 West Manggarai. East Nusa Tenggara.

T: +62 385 41448

F: +62 385 41225

www.floreskomodo.com

www.gokomodo.org

Landscape, Vegetation and Terrain of Komodo National Park

Richard C. Paddock wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Komodo National Park boasts crystal-clear water, miles of deserted beaches and world-class dive sites where rushing currents help protect the reefs from bleaching. A visitor can sail among the park's islands all day and only occasionally see another boat. At Komodo National Park, visitors can approach within a few yards” of the giant lizards. “A ranger stands by with a long stick to fend off any animal that appears threatening, although it seems scant protection.” [Source: Richard C. Paddock, Los Angeles Times, July 5, 2006 ^*^]

Komodo National Park is a landscape of contrasts and unquestionably one of the most dramatic landscapes in all of Indonesia. An irregular coastline characterized by bays, beaches and inlets separated by headlands, often with sheer cliffs falling vertically into the surrounding seas which are reported to be among the most productive in the world adds to the stunning natural beauty of landscapes dominated by contrasting vegetation types, providing a patchwork of colors.

The generally steep and rugged topography reflects the position of the national park within the active volcanic 'shatter belt' between Australia and the Sunda shelf. Komodo, the largest island, has a topography dominated by a range of rounded hills oriented along a north-south axis at an elevation of 500-600 meters.Relief is steepest towards the north-east, notably the peak of Gunung Toda Klea which is precipitous and crowned by deep, rocky and dry gullies. The coastline is irregular and characterized by numerous bays, beaches and inlets separated by headlands, often with sheer cliffs falling vertically into the sea.

To the east, Padar is a small, narrow island the topography of which rises steeply from the surrounding plains to between 200 meters and 300 meters.Further east, the second largest island in the park, Rinca, is separated from Flores by a narrow strait a few kilometers wide. As with Komodo and Padar, the coastline is generally rugged and rocky although sandy beaches are found in sheltered bays.

The mainland components of the park lie in the rugged coastal areas of western Flores, where surface fresh water is more abundant than on the islands of Komodo, Rinca and Padar. The seas around the islands are reported to be among the most productive in the world due to upwelling and a high degree of oxygenation resulting from strong tidal currents which flow through the Sape Straits. Fringing and patch coral reefs are extensive and best developed in the west- and north-facing areas, the most intact being on the north-east coast of Komodo and the south-west coast of Rinca and Padar.

The terrestrial fauna is of rather poor diversity in comparison to the marine fauna. The predominant vegetation type is open grass-woodland savannah, mainly of anthropogenic origin, which covers some 70 percent of the park. The dominant savannah tree is lontar palm, which occurs individually or in scattered stands. Tropical deciduous (monsoon) forest occurs along the bases of hills and on valley bottoms. The forest is notable, lacking the predominance of Australian derived tree flora found further to the east on Timor. A quasi cloud forest occurs above 500m on pinnacles and ridges. Although covering only small areas on Komodo Island, it harbours a relict flora of many endemic species. Floristically, it is characterized by moss-covered rocks, rattan, bamboo groves and many tree species generally absent at lower elevations. Coastal vegetation includes mangrove forest, which occurs in sheltered bays on Komodo, Padar and Rinca.

Wildlife in Komodo National Park

Animals found in Komodo National Park include imperial pigeons, sunbirds, egrets, quail, and exotic mound-building megapodes, horses, wild pigs, crab-eating macaques, flying foxes, cobras, and vipers. Its flora includes orchids, lontar palms, bamboo, soursop, tamarind and custard trees. In the waters of the park live whale sharks, marlin, tuna, whales and dolphins. There are colorful corals, nudibranches, giant clams, turtles, and a plethora of reef and pelagic fish.

The population of Komodo dragons is distributed across the islands of Komodo, Rinca and Gili Motong, and in certain coastal regions of western and northern Flores. Favoured habitat is tropical deciduous forest and, to a lesser extent, open savannah. The mammalian fauna is characteristic of the Wallacean zoogeographical zone, with seven terrestrial species recorded including an endemic rat (Rattus rintjanus) and the crab-eating macaque (Macaca fascicularis). Introduced species, such as rusa deer and wild boar, as well as feral domestic animals including horses and water buffalo, form important prey species for the Komodo monitor. Among the 72 species of bird found on the islands are the lesser sulphur-crested cockatoo (Cacatua sulphurea), the orange-footed scrub fowl (Megapodius reinwardt), noisy friarbird (Philemon buceroides) and common scrubhen. [Source: UNESCO]

The coral reefs fringing the coast of Komodo are diverse and luxuriant due to the clear water, intense sunlight and rapid exchange of nutrient-rich water from deeper areas of the archipelago. Upwelling of nutrient-rich water from deeper areas of the archipelago is responsible for the rich reef ecosystem of which only isolated patches remain due to anthropogenic disturbance. In areas of strong currents, the reef substrate consists of an avalanche of coral fragments, with only encrusting or low branching species. Reefs off the north-east of Komodo have high species diversity. The reefs off Gili Lawa Laut are variable. The marine fauna and flora are generally the same as that found throughout the Indo Pacific area, though species richness is very high, notable marine mammals include blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) and sperm whale (Physeter catodon) as well as 10 species of dolphin, dugong (Dugong dugon) and five species of sea turtles.

The number of terrestrial animal species found in the Park is not high, but the area is important from a conservation perspective as some species are endemic.. Many of the mammals are Asiatic in origin (e.g. deer, pig, macaques, civet). Several of the reptiles and birds are Australian in origin. These include the orange-footed scrubfowls, the lesser sulpher-crested cockatoos and the nosy friarbirds.

Reptiles: Other than the Komodo Dragons, twelve terrestrial snake species are found on the island. including the cobra (Naja naja sputatrix), Russel’s pit viper (Vipera russeli), and the green tree vipers (Trimeresurus albolabris). Lizards include 9 skink species (Scinidae), geckos (Gekkonidae), limbless lizards (Dibamidae), and, of course, the monitor lizards (Varanidae). Frogs include the Asian Bullfrog (Kaloula baleata), Oreophyne jeffersoniana and Oreophyne darewskyi. They are typically found at higher, moister altitudes.

Mammals: Mammals include the Timor deer (Cervus timorensis), the main prey of the Komodo dragon, horses (Equus sp.), water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis), wild boar (Sus scrofa vittatus), long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis), palm civets (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus lehmanni), the endemic Rinca rat (Rattus rintjanus), and fruit bats. One can also find goats, dogs and domestic cats.

Birds: One of the main bird species is the orange-footed scrub fowl (Megapodius reinwardti), a ground dwelling bird. In areas of savanna, 27 species were observed. Geopelia striata and Streptopelia chinensis were the most common species. In mixed deciduous habitat, 28 bird species were observed, and Philemon buceroides, Ducula aenea, and Zosterops chloris were the most common.

Komodo Dragons

Komodo dragons are the world's largest lizard. They can weigh up to 100 kilograms and reach a length of three meters and take prey as large as a water buffalo. They are giant versions of monitor lizards, a reptile that resides all over southern Asia and Africa and are related to goannas found in Australia. Monitors in Malaysia can reach lengths two meters. [Source: Eric Wikramanayake, Smithsonian; The Behavioral Ecology of the Komodo Monitor by Walter Affenberg; James Kern, National Geographic, December 1968]

Indonesia currently has a population of about 3,000 Komodo dragons, according to government data. Most of them — around 1,700 — live on Komodo Island, and around 1,000 more live on Rinca. [Source: Reuters, October 28, 2020]

The name Komodo dragon is kind of nickname. The animals are properly known as Komodo lizards or Komodo monitors. Their scientific name is Varanus komodoensis. They were long thought to related to monitor lizards found elsewhere in Southeast Asia but now it is believed they are the last representative of a relic population of large lizards that once lived across Indonesia and Australia.

Komodo dragons live in tropical savannahs, stream side thickets and coastal regions. There are between 4,000 and 6,000 of them left in the world today, with about half of them on the island of Komodo. The range of the Komodo dragon is smaller than any other large carnivore in the world. Komodo dragons reside only on four largely deforested islands in Indonesia— Komodo, Padar, Rintja, and Gili Motang—and parts of Flores. All of these islands are east of Java and Bali in a chain called the Lesser Sundas. Local islanders call the Komodo dragons "ora." Komodo dragons are good swimmers. It is not known why they don’t live in other places.

Jerome Rivet of Reuters wrote: “Three meters (10 feet) long and weighing up to 70 kilograms (150 pounds), Komodo dragons are lethargic, lumbering creatures but they have a fearsome reputation for devouring anything they can, including their own. They prefer to scavenge for rotting carcasses, but can kill if the opportunity arises. Scientists used to believe their abundant drool was laced with bacteria that served to weaken and paralyse their prey, which they stalk slowly but relentlessly until it dies or is unable to defend itself. But new research has found the lizards are equipped with toxic glands of their own. One bite from a dragon won't kill you, but it may make you very sick and, eventually, defenceless. About 2,500 dragons live on the island named after them ("komodo" means dragon in Indonesian). Along with neighbouring Rinca island, it is the main dragon habitat in the Komodo National Park, created in 1980 to preserve the ancient species. [Source: Jerome Rivet, Reuters, December 22, 2010 ]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MONITOR LIZARDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FOOD factsanddetails.com

BIGGEST AND MOST COMMON MONITOR LIZARDS: ASIAN WATER AND BENGAL MONITORS factsanddetails.com

REPTILES: TAXONOMY, CHARACTERISTICS, THREATENED STATUS factsanddetails.com

LIZARDS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES, ODDITIES factsanddetails.com

KOMODO DRAGONS: CHARACTERISTICS, HABITAT, SENSES, MOVEMENT factsanddetails.com

KOMODO DRAGON BEHAVIOR: FIGHTING, REPRODUCTION, JUVENILES factsanddetails.com

KOMODO DRAGON FEEDING: PREY, HUNTING BEHAVIOR AND VENOM factsanddetails.com

KOMODO DRAGONS AND HUMANS: CONSERVATION, SCIENTISTS, VILLAGERS factsanddetails.com

KOMODO DRAGONS ATTACKS ON HUMANS factsanddetails.com

Komodo Dragon Tourism

Reporting from Komodo National Park, Hannah Beech wrote in the New York Times: The Komodo dragon flicked its forked tongue. Two boys were standing nearby, the perfect size for dragon snacks. A local guide shrugged at their unease and urged them closer to the reptile. Fatal attacks on humans are exceedingly rare, though they do happen. But the oversize lizard lounging near the two young tourists had just gorged on chicken and goat, and was lolling in the kind of digestive stupor Americans might experience after Thanksgiving. It was safe, the guide promised, for a family photograph with the alpha predator, one of only about 3,000 dragons left in the world. [Source: Hannah Beech, New York Times, August 12, 2019]

A few years earlier, Jerome Rivet of Reuters wrote: “They don't breathe fire but Komodo dragons can kill a buffalo or any one of the intrepid tourists who flock to their deserted island habitats. "I feel like I'm in the middle of Jurassic Park, very deep in the past," said Hong Kong visitor Michael Lien during a recent trip to Komodo Island, the main habitat of the threatened Indonesian lizards. Spread out before him is a landscape from the dawn of time — mountainous islands with palm trees plunging down to the azure sea. Lien and his wife are excited and a little nervous at the same time. "What am I supposed to do if a dragon appears suddenly?" he asks Johnny Banggur, the guide on a tour of the island, an almost uninhabited speck in the east of the vast Indonesian archipelago. [Source: Jerome Rivet, Reuters, December 22, 2010 ]

“Armed with 18 years experience and a hefty club for good measure, Banggur dispenses some welcome advice: don't wander from the track and stay with the group. Banggur explains that dragons can devour half their own weight in a single meal. Reassuringly, he adds that they "prefer" buffalo, deer or wild boar and the danger to humans is "very limited". Even so, the Liens have no intention of going anywhere near the menacing reptiles, with their yellow, forked tongues, powerful jaws and sharp claws.

“The island's brave human inhabitants — about 2,000 in all — used to hunt wild boar and deer, thereby competing with the lizards for food. Now they are the dragons' chief guardians. "On Komodo, everything is done for the peaceful cohabitation of humans and dragons," park manager Mulyana Atmadja told AFP.

“Visitors pay to set foot on the islands and take guided tours on designated tracks, always in the company of a ranger. Some 40,000 tourists are expected this year, 90 percent of them foreigners. "We need to act carefully because an excessive number of visitors will trouble the Komodos' natural habitat," Atmadja said. US environmental group The Nature Conservancy has helped the Indonesian authorities shift the local economy into one that sustains both the human and reptilian inhabitants.

“The villagers still fish but no longer compete with the dragons for food. To supplement their incomes they have the exclusive right to sell Komodo miniatures, pearls and other souvenirs. "We've done campaigns to raise the locals' awareness and provide other sources of income for them. The more tourists who come to visit, the more money they can earn," the park chief added. It's worked so well the park managers were able to stop feeding the dragons in 1990. Some of the lizards had apparently forgotten how to fend for themselves and simply waited for tourists to offer them live goats.”

Is the Komodo Area being Ruined by Tourism

The inundation of tourists to Komodo and the surrounding islands is threatening the animals and beauty of the place that draws them there. Hannah Beech wrote in the New York Times: “While Komodo tourism generates significant cash for one of Indonesia’s poorest regions, it has also brought piles of trash, human encroachment and occasional lizard smuggling. Some environmentalists worry that the stampede of visitors has set the ecosystem off kilter. Dragons, they say, should survive on wild deer and pigs, not chickens and goats tossed from the back of a truck by a ranger. “Over all, the number of foreign tourists who visited the entire national park, a UNESCO world heritage site, has doubled between 2015 and 2018, and the number of domestic visitors has increased fivefold. The park is now on the cruise ship circuit, with thousands of people disembarking each day. [Source: Hannah Beech, New York Times, August 12, 2019]

“Concerned about the onslaught of visitors in this far-flung part of Indonesia, provincial leaders want to close the island of Komodo, where the largest population of dragons lives — and where the cruise ships dock — in January 2020. The island would be off-limits for at least a year. Forgoing all that tourist revenue is no easy call for such a poor region, but officials say it is essential for the park’s future. “If we don’t give the dragons their habitat, they will be extinct within the next 50 to 100 years,” said Yosef Nae Soi, the deputy governor of East Nusa Tenggara Province, which includes the islands that make up Komodo National Park.

“But the plan may be thwarted by the Indonesian national government, which will make a final decision this year, officials from the national Ministry of Environment and Forestry say. And even as local officials aim to close the island of Komodo, the national government has unveiled a plan to create 10 “new Balis” across the archipelago nation. It hopes to mimic the success of Indonesia’s most famous holiday isle, which faces its own severe overtourism. “Indonesia needs to diversify its tourism destinations,” said Guntur Sakti, a spokesman for the national Ministry of Tourism.

“One of the 10 “new Balis” is Labuan Bajo, a scruffy port town on the nearby island of Flores that is the gateway to Komodo National Park. So far, the town’s main pier is still mostly occupied with local commerce. Boy stevedores heft bags of instant noodles and dried fish onto wooden boats. Glimmering fish dart past, and children take turns pushing one another off the dock.

“But Labuan Bajo is being transformed, its once picturesque bay now a giant construction site, as the half-finished hulks of luxury hotels destined for dragon-spotters and divers rise in front of primordial jungle. The smell of wet concrete and construction dust mixes with the aroma of clove cigarettes and fried bananas. Plastic bags float in the clear water, like mutant jellyfish. “It’s changing, and that’s good for people like me,” said Sirilus Harmin, a guide who left his mountain home for new opportunities in Komodo National Park.

“Working as the guides who lead walks in the dragon habitat, or operating souvenir stalls, are two of the few options the locals now have to get by since their traditional fishing and hunting ways were curtailed when the national park was formed in 1980. But most of the $300 million in tourism dollars spent in the region does not reach locals, said Shana Fatina, director of the tourism authority board for Labuan Bajo, which is trying to make sure more of the spending flows into the pockets of those who live in the region. “We don’t want the communities to just be an accessory, we want them to be the main focus,” Ms. Shana said. “We want to educate the public that going to Komodo National Park is not like going to an amusement park.”

“If the island of Komodo is closed, the decision will affect not just the humans who wish to visit but also the humans who have lived among the dragons for centuries. They should be relocated, local authorities say. Legend holds that these villagers — about 1,700 live on the island today — share the same ancestors as the dragons. Residents say the reptiles do not bother them much because of this ancient bond. But Mr. Yosef, the provincial deputy governor, seems unsympathetic to the human inhabitants of Komodo. “Komodo Island is for the Komodo dragon,” he said. “The Komodo need a spacious place to live where there are no humans.” And if people refuse to leave the island that has been their home for generations? “If we have warned them and they do not listen, it’s their own fault if the Komodo eat them,” Mr. Yosef said. “It is our offering to the Komodo.”

Jurassic Park at Komodo?

In 2020, Reuters reported: A photo of a Komodo dragon facing a truck has raised concerns about a "Jurassic Park" attraction being built on an Indonesian island. The multi-million dollar site is part of the government's plans to overhaul tourism in Komodo National Park. “The viral image has sparked questions about the impact on the conservation of the famed dragons, the world's largest lizards. Officials said no dragons had been harmed and their safety was paramount.

In 2019, a controversial decision to close Komodo Island — home to most of the lizards — and expel the 2,000 inhabitants who have lived alongside the reptiles for generations was dropped. “Instead authorities said they would introduce a $1,000 membership scheme to visit the island, moving away from mass tourism in a bid to protect the dragons and their habitat.

But around the same time they also unveiled plans for a mass tourist development on neighbouring Rinca Island, which is home to the second-largest population of Komodo dragons. The project has been dubbed "Jurassic Park" in Indonesia after the architects posted a video last month on Instagram of their proposal — set against the music from the dinosaur film franchise. The video generated a lot of attention as it was shared by local campaigners on social media. The development, scheduled for completion by June 2021, is expected to include a tourist information centre and a jetty.

An image of a Komodo dragon facing a construction truck on Rinca Island was widely circulated on Twitter and Instagram. “It was shared by Save Komodo Now, a collective of activists, who wrote: "This is the first time Komodos are hearing the roar of engines and the smell of smoke. What will the future impact of these projects be? Does anyone still care about conservation?" Greg Afioma, a member of the coalition, told the BBC that the group is concerned the planned development will affect the reptiles and the residents. “This kind of massive development disturbs the interaction of the animals. It will change their habitat," he said.

“Government officials told BBC Indonesia they had reviewed the photo being shared on social media and could confirm no Komodo dragons had been harmed during the construction work. “No Komodo dragons will become victims," said Wiratno, Director-General of Nature Conservation and Ecosystems at the Indonesian Ministry of Environment and Forestry. He added that a team from his ministry would go to the island to ensure safety protocols were being followed to protect the dragons.

Komodo Dragon Pit

On Rinca Island, you can see Komodos lying down outside the homes of national park rangers, or "parking" near the officials' homes. Short treks can be organized to look for dragons on Komodo and Rinca. Sometimes dragon wait outside the Loh Liang camp on Komodo. The Poreng Valley, 5½ kilometers from Loh Liang, is another places where they are seen. On Rinca there are no designated viewing areas but the lizards are often seen around the jetty and the PHKA camp at Loh Buaya. Guides know the places where they are most likely to be seen but that is no guarantee the lizards will show up. There is more wildlife on Rinca, including colonies of monkeys, wild pigs, barking deer and fish eagles, than on Komodo.

Previously, to find one, you had to “offer” a goat to attract the Komodo, but now this practice is no longer allowed. In the old days, Komodo dragons were often spotted at Banu Nggulung, a dry river bed about a half hour walk from Loh Liang. A little pit with few benches organized around it was set up here for viewing the lizards. The dragons used to feed on a freshly killed goat there and a number of dragons regularly showed up. Dragons still appear to drink but they no longer show up as reliably as they used to.

In the old days, in morning the giant lizards came to the pit to get fed. When I visited in the 1980s, thinking the whole thing was a little touristy, a friend and I hiked to the pit before the tourists arrived. When we got there, there were no lizards, but soon enough three of them came ambling along. First we watched them from above the pit, then we thought it might be fun to climb into the pit with them. And that is what we did until one turned slightly in our direction and we both went scrambling up a tree. The largest of the three dragons was about eight or nine feet long. It was interesting to watch. When it walked it rocked its shoulders back and forth, sort of like a strutting linebacker. Its forked tongue was constantly going in and out, curling and probing.

Finally the others arrived with the dragon food, a live goat. But it didn't stay alive for long. The Indonesian guides cut its throat. After which it was tied to a rope and dangled above the heads of the dragons. The lizards obviously had been through this routine before and there was no way they were going to leap into the air to grab the dead goat. When it was dropped down to them, that is when they started ripping it apart. One of the little dragons got a piece of intestine stuck between its teeth, sort of like we do with a piece of corn, and I felt sorry for it because what ever it did it couldn't it out.

This went on for a while. Later the guides carried the goat carcass out of the pit and placed it a little corral next to the tourists. At first the lizards didn't want to climb out of the pit so a couple of park ranger climbed into the pit and prodded one of them out with a long forked stick. The big lizard obliged and everyone got good close-ups of the beast snapping its jaw shut on a piece of goat leg.

The dragons are no longer fed the goats on the grounds that had become lazy and less able to find food of their own. Visitors now hire dragon finders who take them though the forest and underbrush, looking for dragons.

Hiking in Komodo Dragon Country

Brendan Borrell wrote in Smithsonian Magazine, “It didn’t seem prudent to bring two small children along. We had just docked at a remote island in southeastern Indonesia, and the five-hour hike would traverse a rocky, exposed ridge in the baking heat of the dry season. My companions—a blond Frenchman named Fred, his wife and their two kids—were dressed for a game of shuffleboard. My concern heightened when I saw he had a single water bottle for the four of them. Also, there were dragons. [Source: Brendan Borrell, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2013]

“Komodo National Park has become Indonesia’s hottest tourist spot this side of Bali. Our starting point in Labuan Bajo, on the island of Flores, was packed with hip cafés, hostels and diving shops. Cruise companies offer a two-day expedition to parkland on Komodo and Rinca islands. Komodo, about five times the size of Manhattan, got a makeover in the late 1990s, when the Indonesian government asked the Nature Conservancy and the World Bank to help it protect the island’s biodiversity, develop hiking trails and build a visitor center. Even with these amenities, the destination’s popularity is surprising. Whale-watching may appeal to our spiritual side, while a glimpse of an orangutan or other primate cousin tugs at an evolutionary heartstring. The Komodo dragon, I believe, taps into our basic fears: a living incarnation of the fictional monsters that haunt our imaginations.

“Our guide that August morning, Ishak, lifted his forked stick—a defense against snapping jaws—and we marched into the bush. Even the vegetation is reptilian: Crocodile trees with spiky bark sprout from volcanic soils, while Lontar palms tower over the upland savanna. After only a ten-minute walk we came to a gallery of tamarind trees shading a pit of mud and greenish scum. A female Komodo dragon was sprawled next to a tree, her black obsidian eyes unreadable. The beaded folds of her flesh hung from her neck and she had kicked her rear legs behind her with the insouciance that comes from being at the top of the food chain. Luckily, she was still digesting a meal from earlier that week—a small deer, according to Ishak—and in her postprandial stupor would probably not be pondering cuisine for another month. Up ahead, however, I knew there were dragons in the brush, possibly hungry ones. At the top of a pass, a white cross commemorates Rudolf Von Reding Biberegg, an elderly Swiss tourist who vanished in 1974, presumably killed by a Komodo dragon. “He loved nature throughout his life,” the epitaph says.”

“August is the height of the breeding season and, during our visit, most Komodo dragons were defending their nests or looking for mates far from established trails and water holes. Fred and his family were chipper as usual as we passed mounds of dirt and rock that were 10 to 20 feet in diameter and at least as tall as his 9-year-old son. The mounds are the nests of chicken-like birds called orange-footed megapodes, which don’t incubate their eggs with body heat but bury them atop plant matter that produces heat as it decays. The dragons remodel these nests for their own eggs, and guard them for six months, a rather long incubation.

“By noon, we were out of the forest and had crested the ridge, gazing out across golden meadows and aquamarine waters that could have easily been mistaken for a southern California scene. We then trotted down the mountain. I slipped three times—unlike Fred’s 6-year-old daughter, who held out her arms like she was flying and didn’t trip once on the crumbling slope. When we got to the bottom and arrived at the last stop on the hike, Loh Sebita camp, we saw our last dragon, a somewhat pathetic creature lounging next to a wooden building on stilts, the kitchen. “If the dragon can’t hunt, he might come here,” Ishak says. “Sometimes the cook may throw out a chicken bone.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Indonesia Tourism website ( indonesia.travel ), Indonesia government websites, UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Japan News, Yomiuri Shimbun, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026