LIFE IN BALI

Many people still earn money from agriculture, and rice grown in paddies and terraces has traditionally been the most important crop by far. The climate and water supply make it possible to grow two or three crops a year. However, there is little mechanization. The plots are too small for that to be efficient. Most plowing is done by water buffalo, and planting and harvesting are done by hand. Although the soil is very rich, multiple crops require the use of fertilizers. In the western part of the island, coffee is a profitable enterprise. Oranges are a cash crop in the north.

Rice is the main crop. Balinese people eat about a pound of rice per day, compared to an average of 22 pounds per year for Americans. Traditionally, the government has controlled the price of rice and purchased any surpluses. Rice is viewed as a manifestation of Dewi Sri, the goddess of life and fertility. Young girls who make offerings at temples first moisten their foreheads, temples, and upper chests with holy water, then stick moistened rice to these spots. This action symbolizes the absorption of life forces. [Source: "Rice, the Essential Harvest" by Peter White, National Geographic, May 1994]

Motorbikes are the predominant form of transportation. They can carry up to five passengers and extremely bulky loads. Government-provided medical care and Western medicine is widely available and commonly used. At the same time, indigenous medical beliefs remain influential. Illness and misfortune are often understood as the result of angry spirits or ancestors, witchcraft, or imbalances in the body’s humors, and many Balinese combine biomedical treatment with traditional healing practices. The Balinese apply a mixture of rice paste and tenekeh root to their skin to make it feel hot or cold to the touch, depending on their preference.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BALINESE: LANGUAGE, CUSTOMS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

BALINESE SOCIETY: GROUPS, CASTE, THE SUBAK SYSTEM factsanddetails.com

BALINESE FAMILY: MARRIAGE, WOMEN, RITES OF PASSAGE factsanddetails.com

BALINESE RELIGION: HINDUISM, SPIRITS, TEMPLE LIFE, PRIESTS factsanddetails.com

FUNERALS AND DEATH IN BALI factsanddetails.com

BALINESE CALENDAR factsanddetails.com

BALINESE HOLIDAYS, FESTIVALS, RITUALS, CEREMONIES AND OFFERINGS factsanddetails.com

BALINESE CULTURE AND ARTS factsanddetails.com

BALI: GEOGRAPHY, LIFESTYLE, REPUTATION, GETTING THERE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF BALI: ORIGIN, KINGDOMS, MASS ROYAL SUICIDES factsanddetails.com

MODERN HISTORY OF BALI: VOLCANIC ERUPTIONS, TERRORISM, RECOVERY factsanddetails.com

TOURISM IN BALI: CELEBRITIES, RESILIENCE AND ITS RISE FROM A 1930s SOCIALITE ARTIST COLONY factsanddetails.com

NEGATIVE SIDE OF TOURISM IN BALI: OVERDEVELOPMENT, BAD BEHAVIOR DONALD TRUMP factsanddetails.com

Agriculture in Bali

For centuries, Balinese livelihoods have been rooted in wet-rice agriculture, supported by a sophisticated irrigation system that coordinates planting on mountain terraces and coastal plains. About 70 percent of the population continues to depend on agriculture for income. Where water is abundant, particularly in the southern lowlands, wet-rice cultivation predominates, while in drier regions farmers grow nonirrigated crops such as dry rice, maize, cassava, and beans. In densely populated areas, sharecropping has become increasingly common. Along the coasts, coconuts are widely cultivated, while fruits such as citrus and salak (snakefruit) are produced for markets beyond the island. Livestock, including pigs, ducks, and cattle, are commonly raised, and fish are both caught at sea and farmed in flooded rice paddies. [Source: Ann P. McCauley, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University; A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Double-cropping of rice is widespread, and government-supported programs have introduced improved rice varieties that allow up to three harvests a year in some areas. Mechanized plows are used mainly on flat land, but in most places, especially on steep terraced hillsides, water buffalo continue to pull plows in small family fields. Although Bali’s volcanic soils are naturally fertile, intensive multi-cropping requires the use of chemical fertilizers. The government supports rice farmers by protecting prices and purchasing surplus harvests for redistribution. In addition to rice, western Bali supports a profitable coffee-growing region, while oranges serve as a major cash crop in the north.

Agricultural labor is divided by gender but remains flexible. Men typically plow and prepare the fields, while both men and women plant and harvest crops together by hand, often in large cooperative groups. Weeding is usually done by family members. Women tend household gardens, care for pigs, and operate small food or snack stalls, often controlling the income generated from these activities. Men are primarily responsible for cattle kept near garden areas. Childcare is led by women, with assistance from husbands and other family members. While men and women may substitute for one another in domestic and farm work when necessary, ritual responsibilities are more strictly divided: men serve as priests, while women prepare the elaborate offerings essential to religious ceremonies.

Land is regarded as belonging to a patrilineal descent group. In much of Bali, property is not defined by a formal title. Land tenure in Bali combines legal ownership with customary principles. Rice fields and garden land are formally registered in the name of an individual man, although his sons may actively work the land. At the village level, land is understood to belong to a patrilineal descent group, with the current owner holding the right to use or transfer it. In the past, royal families controlled extensive landholdings, reflecting their political and ritual authority within Balinese society.

Work and Economic Activity in Bali

Agriculture and government jobs have traditionally been the main sources of employment. Many tourism-related jobs are performed by non-Balinese people. Carvers, painters, and other craftsmen largely work on consignment for art shops. In the early 2000s, the average wage for many people was $50 per month.

The local Balinese economy has traditionally been rooted in agriculture and government employment, particularly in offices and schools. Although Bali is internationally known for tourism, many local households have little direct involvement in the tourist sector. The island has no significant heavy industry and only limited light manufacturing. In areas frequented by visitors, wood carvers and painters often produce artworks and souvenirs for sale, typically working on consignment through local art shops. [Source: Ann P. McCauley, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University; A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

At the same time, many Balinese are employed in cottage and medium-scale industries. Since the 1970s, the garment industry has grown rapidly, alongside factories engaged in printing, food canning, and the processing of coffee and cigarettes. Tourism, fueled by large numbers of both foreign and domestic visitors, has become an important source of employment, generating jobs in hotels, travel agencies, guiding and taxi services, craft shops, and also providing financial support for performing and visual arts.

Traditionally, economic life revolves around large markets in the towns and smaller markets in the villages. Villagers have traditionally brought their animals and harvested crops here to buy and sell consumer goods. Women have traditionally dominated the markets. Tourism changed the country. Many people got jobs as waiters, drivers, and craftsmen oriented toward the tourist market. . These jobs brought wealth, and people could buy televisions and refrigerators. Many people got used to their new lifestyle, got credit cards, and took out loans. When tourism drops, they can't pay back their debts.

In towns, skilled artisans and merchants such as goldsmiths, tailors, and shopkeepers supply a wide range of consumer goods. Every town maintains a market where vegetables, fruit, packaged foods, and livestock such as pigs and chickens are bought and sold. In some villages, markets operate on a rotating schedule. Villagers—most often women—bring agricultural produce to sell and return with manufactured goods to resell door to door or in small shops. In other cases, traveling merchants visit villages to purchase farm products or sell items such as cloth, soap, and patent medicines, while men typically handle the sale of cattle at central livestock markets.

Balinese, the Sea and Seaweed

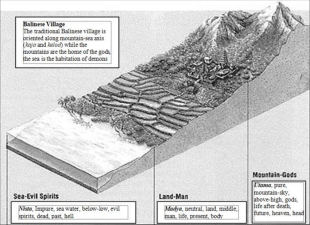

The Balinese have an ambivalent relationship with the sea. They both fear and need it for food. Their religion emphasizes that gods are found in mountains and other high places; the sea is mainly a place where giants, demons, and monsters dwell. Jukeng are traditional outrigger boats painted in cheerful colors.

In shallow bays and seas off the east coast of Bali, seaweed is grown in large checkerboard-like plots. In the early 2000s, a crop could earn 25 cents per pound and is sold to Japan for use in food and as an ingredient in a wide range of products, including processed meat, toothpaste, mascara, whipping cream, and wrinkle cream. It is also used in beer.

The seaweed is planted, harvested, and dried. Farmers typically work at low tide, attaching cuttings to lengths of rope and stringing them between wooden stakes driven into the seabed. The dried seaweed is sold to a broker, who ships it to Java. From there, it is shipped to food and cosmetics companies.

A kilogram of seaweed sold for about 38 cents in the early 2000s. A that time farmers earned about $50 a month. After the Bali bombing, many Balinese took up seaweed collecting to make money. There was a 30 percent increase in the seaweed market.

Living in the Shadow of Mt. Agung

Mt. Agung is Bali’s highest mountains and most active volcano. Andrew Marshall of Associated Press wrote: Tourism remains Bali's biggest industry. And by the grace of Agung and its neighbor, Mount Batur, houses that once nestled in fields of chilies and onions now overlook quarries filled with workers shoveling volcanic sand into trucks. [Source: Andrew Marshall, Associated Press, January 2008]

Not everyone has been lifted by the rising tide of tourism. Seven hundred people in the village of Trunyan squeeze into a mountain stronghold near Mount Batur. Their ramshackle houses cling to a sliver of land along a lake in a vast caldera. The villagers fish in dugout canoes and grow crops on the steep shoulders of the caldera. The village's creation myth explains its isolation, telling how a wandering Javanese nobleman fell in love with a goddess who lived in a giant banyan tree. She agreed to marry him, but only if he covered his tracks so nobody else could follow him from Java.

While tourism has brought breakneck development to the rest of Bali, Trunyan's cherished isolation now spells economic marginalization. Elders watch helplessly as a younger generation traces the same path to Bali's towns and cities as Batur's rock and sand. "There are no jobs here, no opportunities," admits Made Tusan, a teacher at Trunyan's only school.

As if economic malaise weren't enough, a recent catastrophe added to the litany of woes. A giant banyan tree that had shaded the village for centuries crashed to the ground during a storm, flattening the village temple, though miraculously sparing the holy statue of Dewa Ratu Gede Pancering Jagat, the local deity.

A village elder, I Ketut Jaksa, blames the disaster on Balinese politicians and businessmen. He "won't name names," he says guardedly, but he insists they angered the volcano deity by praying to advance their careers while ignoring Trunyan's growing disrepair. Others blame the new road, which recently connected the village to the rest of Bali, destroying its isolation and leaving it open to spiritual contamination.

Balinese Villages

Balinese villages (desa) are defined by a group of people who worship at a common temple. Settlement can be centered around the temple or scattered over a wide area. Most temples are located near the intersection of a major and minor road. Both villages and house yards are ideally laid out with the most sacred building situated nearest Mount Agung and the least sacred ones nearest the sea. Many villages are filled with barking dogs. [Source: Ann P. McCauley,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

In mountainous areas Balinese villages tend to be compact, while in the lowlands they are more dispersed among fields and gardens. Each village has three main temples, usually located separately and aligned symbolically. The most kaja temple, the pura puseh, is associated with the god Wisnu and purified ancestors. At the center stands the pura bale agung or pura desa, dedicated to Brahma. The most kelod temple is the pura dalem, linked to Siwa and the spirits of the not-yet-purified dead. [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Many villages have elementary schools but most villagers have to go to the nearest town for access to a clinic. Each village has at least three, temples usually located separately and aligned symbolically: 1) a “pura puseh”, dedicated to the village founders; 2) a “para desa”, dedicated to the spirits that protect the village; and 3) a “para dalem”, the temple of the dead. Many villages have several dozen temples. Each Balinese belong to six temple congregations: three in their village and others scattered around the island.

Balinese Homes

Traditional Balinese houses are enveloped by palms, hibiscus, and night-blooming jasmines. House yards are open. Walled areas contain buildings, including a family temple facing Mt. Agung. Wealthy families have large yards with brick, tile-roofed buildings decorated with elaborate carvings on stone and wood. Poor families have smaller yards with buildings and walls made of mud and wattle. [Source: Ann P. McCauley,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Traditionally, Balinese families lived in walled compounds (uma) inhabited by a group of brothers and their respective families. Within the compounds, grouped around a central courtyard, are separate buildings for cooking, storing rice, keeping pigs, and sleeping. Each compound has a shrine (sanggah). A thatched pavilion (bale) serves for meetings and ceremonies. A walled-in pavilion (bale daja) stores family heirlooms. Rivers serve for toilet and bathing functions.

On the kelod (south, ocean) side of the compound, there are separate cooking pavilions for each family. The sleeping areas are arranged based on social status and function. The grandparents, parents, and the senior brother sleep on the kaja (north, facing Mt. Agung) side. Guests sleep on the east side, and children sleep on the west side. The family shrine (sanggah) is in the kaja–east corner. The buildings where community groups meet are called bale banjar. Today, these buildings often have modern amenities, such as a television and ping-pong tables.

Some houses are set up so that a stream goes underneath the toilet and another flows near the kitchen where dishes are cleaned by placing them in a rattan basket in the running water. The temperature is always between 75 and 85̊F and no attempts are made to get rid of creepy crawly creatures and insects . In fact it is considered taboo to move into a house before the spiders and geckos have moved in. ==

See Separate Article: BALINESE HOUSES, TEMPLES AND ARCHITECTURE factsanddetails.com

Balinese Clothing

For everyday dress, Balinese women typically wear sarongs paired with a cotton blouse, T-shirt, or a kebaya, a fitted long-sleeved jacket. In Bali, the kebaya is secured at the waist with a wide, brightly colored sash. Men commonly wear sarongs along with an udeng, the traditional Balinese headcloth, which is characteristically knotted at the front.

Traditional dance costumes are more elaborate. Dancers wear tightly wrapped sarongs (kain) that extend from the chest to the ankles. A deep torso band is wrapped around the body, often layered with a long apron and a colorful collar made of soft leather painted with gold. Dancers also wear ornate headdresses and hip ornaments crafted from painted leather in bright colors and decorated with frangipani flowers. Boys as well as girls wear flowers, makeup, and decorative costumes when participating in dances and ceremonial events. [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

In work settings outside the home—particularly office and shop jobs—Balinese people generally wear Western-style clothing. At home, men may wear shorts and a tank top or, alternatively, a sarong. Men’s traditional attire includes the kamben sarung, a tube sarong made from endek or batik cloth. For temple ceremonies, a songket cloth woven with gold or silver threads is worn over the kamben, while for major rites of passage the kamben itself is made of songket. Men pay close attention to how both the kamben and the udeng are tied for formal occasions. The lower edge of the kamben hangs longer in front—often held up while walking—and may be hitched up like trousers for working in the fields.

Women traditionally wear a kamben lembaran, a non-tube sarong usually made of mass-produced batik, often secured with a sash (selempot) when outside the home. Going about in public with the breasts uncovered has long been uncommon. When carrying loads on their heads, women place a cloth between the head and the load. For temple ceremonies, women wear a sabuk belt wrapped tightly around the body up to the armpits, with a kebaya jacket worn over it; however, kebaya jackets and selempot sashes are not worn for rites of passage. Because many women now keep their hair short, wigs are often used to complete traditional ceremonial hairstyles.

The most popular locally made cloth is endek, a type of ikat with a tie-dyed weft and solid warp. Another precious kind of ikat is geringsing, which has a complicated dyeing process that takes months to complete.

See Textiles Under ART AND CRAFTS IN BALI factsanddetails.com

Balinese Food

Like the food of other regions in Indonesia, Balinese food is rice as the central dish served with small portions of spicy, pungent vegetables, fish or meat and served almost always with sambal or chili paste. Bali is one of a few of the regions in Indonesia whose majority of its people are non Muslims, thus eating pork is okay. Babi guling or roasted suckling pig is a specialty, as is bebek betutu, smoked stuffed duck wrapped in bamboo leaves. Authentic Balinese food can be found in many settings across the island. Warungs, or small local eateries, are ideal for affordable, traditional meals. Night markets offer a lively atmosphere and a wide selection of street foods, from fried rice and satay to local snacks.

The Balinese typically eat on their own, quickly, and at any time. They often snack frequently. Everyday food is made up of rice and vegetable side dishes, sometimes with a bit of chicken, fish, tofu (bean curd), or tempeh (fermented bean curd), and seasoned with chili sauce (sambal) made fresh every day. Many dishes require basa genep, a standard spice mixture composed of sea salt, pepper, chili, garlic, shrimp paste, ginger, and other ingredients. For special celebrations, men prepare ebat, chopped pig, or turtle meat mixed with spices, grated coconut, and slices of turtle cartilage or unripe mango. [Source: “Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of World Cultures,” The Gale Group, Inc., 1999 /=]

Typical dishes popular with tourists include Sate Lilit (minced meat satay) and Nasi Campur (mixed rice), and a wide variety of spicy sambals. Many dishes are cooked or wrapped in banana leaves, such as Pesan Be Pasih (seasoned fish). Well-known Indonesian staples like Nasi Goreng (fried rice) are widely available, while traditional sweets such as Laklak add a local touch to desserts. Sate Lilit is made from minced fish, chicken, or pork blended with coconut and spices, wrapped around lemongrass sticks and grilled. Bebek Betutu consists of duck or chicken slow-cooked until tender in a rich spice paste. Popular across Indonesia but commonly found in Bali as well are Gado-Gado, a vegetable salad with peanut sauce, and Nasi Goreng or Mie Goreng, everyday favorites enjoyed at any time of day.

Babi Guling — Balinese Roast Suckling Pig

David Farley of the BBC wrote: Babi guling — which directly translates as “turning pig” as it’s roasted on a hand-turned spit over an open fire — is an unlikely find in Indonesia, a country that has the largest Muslim majority population in the world. But Bali is something of an anomaly: much of the population practices an off-shoot of Hinduism that’s been combined with local spiritual traditions, which means that pork — normally verboten in Muslim countries — is fair game here. In fact, eating babi guling in Bali is perhaps the country’s most quintessential dining experience. [Source: David Farley, BBC, November 20, 2015]

Ask anyone where to eat babi guling in Ubud and they’ll point you in the direction of Ibu Oka (Jalan Tegal Sari No. 2; 62-3-61-97-6345), a famed babi guling spot that many claim sets the bar for the dish. Here, I met up with Chris Salans, a Franco-American chef who runs the kitchen at Ubud’s acclaimed restaurants Mozaic and Spice. He’s lived in Bali for 20 years and knows a thing or two about babi guling.

With heaping plates of babi in front of us, Salans explained the various parts that make up the dish: “The key to a good babi guling”, he said, “is that it shouldn’t just be all about the meat. There should be a good veg” — in this case, spice-spiked long beans — “as well as fluffy rice, tender meat and a piece or two of super crispy skin. “Oh yeah,” he added, “there should be a spice mix that pops in your mouth.”

That spice mix is called basa gede, literally meaning “big spice mix”, and the name doesn’t exaggerate. It consists of shallots, garlic, ginger, ginger-like galangal, kencur (aka “lesser galangal”), turmeric, macadamia-like candle nut, bird’s eye chilli, coriander, black peppercorn, salam leaves (an Indonesian bay leaf) and salt, plus a shrimp paste mixed in. Like salt and pepper to the Balinese, it infiltrates nearly every dish on this 111km-long, 152km-wide island.

It’s impossible to make babi guling at home unless you cook an entire pig. You can’t selectively buy a piece of pork from a supermarket and hope it will turn out like true Balinese babi guling, which is why most people get it small restaurants — including favourites such as Candra in Denpasar (Jl Teuku Umar, Denpasar; 62-3-61-22-1278) and Dobel in Nusa Dua (Jalan Srikandi No 9, Nusa Dua; 62-3-61-77-1633). Or, they go to people like Putu Pande, who has spent the last decade making babi guling in his back courtyard for various restaurants and private celebrations.

Sharing Coffee and a Meal with a Balinese Family

On a visit the home and family of a Balinese woman named Ketut, Mark Eveleigh of the BBC wrote: It is virtually impossible to visit without drinking a glass of the kopi that was harvested locally and roasted at a house just down the road. And why would you refuse? Ketut’s sweet, strong, black coffee is some of the best in Bali and is such a delicious caffeine- and sugar-rush that you must force yourself to stop before you reach the half-inch of grainy mud at the bottom of the glass. Long before you’ve reached that stage, Nenek [the grandmother in the family] will have emerged again from the kitchen with a little plate of sumpit (rice-flour dumplings steamed in banana leaves) or bantal (rice, groundnuts and banana steamed in young palm leaves). If there are no sweet snacks, there will, at least, be some freshly harvested pisang emas. These so-called ‘gold bananas’ are the most deliciously sweet bananas in the world. [Source: Mark Eveleigh, BBC, June 21, 2018]

Sudana [Ketut husband] joins us for coffee and we chat about the ever-changing conditions of the rice paddies — a perennial preoccupation in rural Bali. Nenek sits nearby, silently but contentedly occupied with her chores. It’s said that in rural Bali that more than half of a family’s income is spent on the endless cycle of temple ceremonies, and both Nenek and Ketut seem to fill every spare minute with preparing the little offerings that are the spiritual bread and butter of the ‘Island of the Gods’.

Nenek, occasionally smiling at us, staples intricate little leaf saucers together using splinters of palm stem. She’s so accustomed to the work that she barely needs to look. These saucers will often be used to present coffee to the spirits that act as temple guardians, to keep them alert for the demons that haunt the beaches. At other times, she might be busy weaving ketupat, the tiny latticework baskets that look like Balinese Rubik’s Cubes. They’re so complicated that I’ve never known a foreigner to succeed in making one, yet both Ketut and Nenek are able to complete one in less than a minute. (Ketut’s record by my stopwatch was 28 seconds.) These ketupat are reserved for bigger ceremonies. They’re half filled with rice and boiled for several hours so that the rice swells into a solid block. It’s unusual if a week goes by without a large ceremony somewhere in the immediate neighbourhood.

It’s late afternoon by now, and Sudana, with typical Balinese hospitality, will almost certainly invite you to stay for dinner. Ketut might have prepared her deliciously spicy nasi goreng (fried rice), and there will be some vegetables in sauce. There might very likely be some sea-fish satays, barbecued using a clever invention that avoids the endlessly finicky turning of satay sticks: instead, a whole bunch of sticks are impaled in a hunk of banana tree so Sudana can simply turn the entire batch all in one go. There might be some shreds of chicken in sauce if there’s been a ceremony in the street lately, but that’s the only time meat is likely to be on the menu.

Fridges are a relatively recent arrival here so the community still has the habit of sharing among the neighbours. Ketut will offer you a fork and spoon to eat with, but a beaming smile is sure to break out on Sudana’s face if you decide to ‘go local’ and eat with your hand: “Lebih enak!” he chortles happily — more delicious that way.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Indonesia Tourism website

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026