BALI

Bali is home to about 4.4 million people. About 90 percent are Balinese. The other 10 percent are Chinese, Muslim Javanese and other ethic groups. About 80 percent of the island's population live in the southern part of the Bali. Much of the western part of Bali is uninhabited jungle, where tigers lived until the 1940s.

Bali is a relatively small, diamond-shaped island. It covers only 5,580 square kilometers (2.155 square miles) and measures 140 kilometers (85 miles) across from east to west, and 80 kilometers (50 miles) from north to south. No part of the island is more than 30 kilometers from the sea. The inhabited areas are mostly in the south and east. The landscape includes large volcanos and dense forests in the north and a coastal plain in the south. In between are steep ridges and ravines covered with "cascades of rice terraces" and rimmed by coconut palms, bamboo and banana trees.

Bali has long enjoyed the reputation of being an enchanting place where everyone seemed to be an artist, everyday was a festival, fruit and flowers grew in abundance, and gentle heavily-made-up little girls perform mystical dances. In the minds of many people minds Bali is as close to paradise as you can get. It has beautiful scenery: temples, rice terraces, beaches, volcanoes and beautiful villages placed among lush vegetation. For better or worse these things have been exploited by the tourism industry. In recent years Bali has suffered from its reputation..Many places have became crowded, overdeveloped and spoiled. The nice places are increasingly becoming fancy resorts accessible to rich. While the places accessible to everyone else have become congested and touristy.

Bali was colonized by Hindu invaders in the 9th century and unlike most of the rest of Indonesia the island refused to bow to Islam when it arrived several centuries later. Bali is the only Hindu island in Indonesia and contains one of the largest concentration of Hindu people outside of India. Balinese Hinduism incorporates elements of animism and ancestor worship, draws few distinction between secular, religious and super natural life; and makes no real distinction between the living and dead. The arts are held in high esteem. Artist include painters, woodcarvers and basket makers. One thing you see everywhere are wonderfully carved and colored wooden flowers. The Balinese are regarded as warm, mellow and fun loving.

Books: “Island of Bali” by Miguel Covarrubias (1937) is regarded as the classic from the period when Bali was discovered by the rich and famous. There are multitude of other books, many of them dealing with Balinese arts and culture. Margaret Mead spent some time in Bali in the 1930s. She learned the language, listened to folk tales and myths and wrote a book called “Balinese Character” with her husband Gregory Bateson.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BALI: GEOGRAPHY, LIFESTYLE, REPUTATION, GETTING THERE factsanddetails.com

MODERN HISTORY OF BALI: VOLCANIC ERUPTIONS, TERRORISM, RECOVERY factsanddetails.com

BALI BOMBING IN 2002 factsanddetails.com

TOURISM IN BALI: CELEBRITIES, RESILIENCE AND ITS RISE FROM A 1930s SOCIALITE ARTIST COLONY factsanddetails.com

NEGATIVE SIDE OF TOURISM IN BALI: OVERDEVELOPMENT, BAD BEHAVIOR DONALD TRUMP factsanddetails.com

BALINESE: LANGUAGE, CUSTOMS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

BALINESE SOCIETY: GROUPS, CASTE, THE SUBAK SYSTEM factsanddetails.com

BALINESE FAMILY: MARRIAGE, WOMEN, RITES OF PASSAGE factsanddetails.com

LIFE IN BALI: VILLAGES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK, AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com

BALINESE RELIGION: HINDUISM, SPIRITS, TEMPLE LIFE, PRIESTS factsanddetails.com

FUNERALS AND DEATH IN BALI factsanddetails.com

BALINESE CALENDAR factsanddetails.com

BALINESE HOLIDAYS, FESTIVALS, RITUALS, CEREMONIES AND OFFERINGS factsanddetails.com

BALINESE CULTURE AND ARTS factsanddetails.com

Early History of Bali

Though no artifacts or records exist that would date Bali as far back as the Stone Age, it is thought that the very first settlers to Bali emigrated from China in 2500 B.C., having created quite the evolved culture by the Bronze era, in around 300 B.C. This culture included a complex, effective irrigation system, as well as agriculture of rice, which is still used to this day. Bali’s history remained vague for the first few centuries, though many Hindu artifacts have been found, which lead back to the first century, indicating a tie with that religion. Though it is strongly held that the first primary religion of Bali, discovered as far back as A.D. 500 was Buddhism. Additionally, Yi-Tsing, a Chinese scholar who visited Bali in the year A.D. 670 stated that he had visited this place and seen Buddhism there.

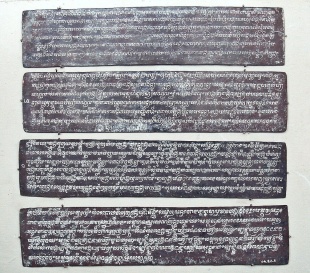

The earliest evidence of human habitation of Bali are some 3000-year-old stone tools and earthenware vessels from Cekik.. The earliest people in Bali likely practiced some form of animism (belief in spirits). Buddhism and Hinduism arrived via Java. The oldest writing found in Bali are stone inscriptions that date to the 9th century. By that time rice was being extensively grow under the “subak” system. From what can be ascertained from archeological, literary and oral evidence, the indigenous people of Bali came into increasing contact with people from Java around the A.D. 5th century and were influenced by the Hindu and Buddhist religions found there but also by the language and political traditions associated with them. It is not known whether people that introduced these traditions were Indians or Javanese or both.

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theatre Academy Helsinki wrote: “Ancient megalithic ritual sites bear witness to the long history of this island, although they have been covered over by later terraced rice fields and villages. Archaeological finds include bronze artefacts from before the present era. A large bronze drum or kettle gong called “The Moon of Pejeng”, stored in a temple in the small village of Pejeng, indicates contacts with the Dong-son bronze culture, which spread from Southern China to South-East Asia in the first millennium B.C. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theatre Academy Helsinki **]

Origin of the Balinese

The Balinese people emerged from a long process of migration and cultural mixing. Their earliest ancestors were Austronesian (Proto-Malay) settlers from mainland Southeast Asia, who introduced rice farming, Austronesian languages, and ancestral belief systems. Over time, these foundations were reshaped by outside influences, especially from India and Java, producing the distinctive Balinese culture seen today. [Source: Google AI]

From the first millennium CE, contact with Indian traders and priests brought Hinduism, Sanskrit, Indian epics, and new ideas of kingship. These influences transformed local society and laid the basis for Balinese Hinduism. The most decisive change came between the 14th and 16th centuries, after the fall of the Hindu Majapahit Empire in Java. Javanese nobles, priests, and artists migrated to Bali, strengthening Hindu-Buddhist traditions, refining art and literature, introducing court culture and caste distinctions, and helping prevent the spread of Islam to the island.

Linguistically, Balinese belongs to the Austronesian family, within the Bali–Sasak–Sumbawa group, and is related to Javanese and Malay. Its core grammar and vocabulary are Austronesian, but it absorbed many Sanskrit and Old Javanese (Kawi) terms, especially for religion, ritual, and formal speech. Early inscriptions from the 9th–11th centuries show Old Balinese written in scripts derived from Indian Brahmi and Pallava models, such as the Belanjong inscription (914 CE). Balinese also developed distinctive sound changes and a complex system of high and low speech levels, reflecting social hierarchy.

Genetic evidence mirrors this layered history. Most Balinese ancestry comes from the Austronesian expansion that shaped much of Indonesia, with additional Austroasiatic contributions from mainland Southeast Asia. There is also a significant South Asian component—about a tenth of the paternal gene pool—linked to centuries of trade and Indian cultural influence. Smaller traces of much older, pre-Austronesian populations remain as well. Together, these genetic, linguistic, and cultural layers reflect Bali’s long history of migration, contact, and adaptation.

Infusion of Buddhism and Hinduism Into Bali

Archaeological evidence, inscriptions, and written and oral traditions show that Bali’s indigenous population began sustained contact with Java after the A.D. fifth century. Through these contacts came Hindu and Buddhist ideas of religion, language, and political organization. It is unclear whether these influences arrived directly from India or through Indianized societies in Java. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theatre Academy Helsinki; Ann P. McCauley, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/ Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

From the A.D. early centuries, Bali increasingly absorbed Hindu-Buddhist culture and, at times, Chinese influences, visible in architecture, visual arts, and theatrical traditions such as masks and story themes. Java played a decisive role in Bali’s development, frequently dominating the island. Bali did not have its own king until the tenth century. In the late tenth century, a dynastic marriage between a Balinese prince and an East Javanese princess briefly united Bali and East Java. Despite close ties, Bali was never fully Javanized and developed its own form of Hindu culture, which later resisted the spread of Islam that transformed Java from the fourteenth century onward.

By the eleventh century, Javanese influence had deepened. Airlangga, born to a Balinese king and a Javanese queen, united Bali with an eastern Javanese kingdom. After political turmoil in Java, he later ruled East Java and appointed his brother, Anak Wungsu, as ruler of Bali around A.D. 1011. This period saw strong exchanges in politics, religion, art, and language. Old Javanese (Kawi) became the language of the Balinese elite, and many Javanese customs were incorporated into Balinese life.

Balinese Hindu Kingdom

As Islam spread across Indonesia, Bali became a refuge for Hindu nobles, priests, and artists, allowing Hindu traditions to survive and flourish. Although Bali experienced periods of foreign domination, it remained largely autonomous until 1284, when the East Javanese ruler Kertanegara conquered the island. After his assassination in 1292, Bali regained independence, but in 1343 it was again brought under Javanese control by Gajah Mada of the Majapahit Empire. [Source: Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theatre Academy Helsinki; Ann P. McCauley, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/ Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries, Bali endured as a Hindu kingdom while much of Indonesia became Islamic or Christian. It influenced nearby regions, particularly Lombok, and at times exercised regional power. For several centuries Bali was intermittently ruled by Majapahit, until that Hindu-Javanese empire fell to Muslim forces in 1527.

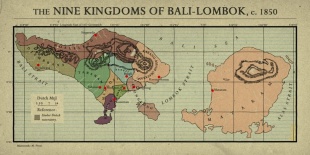

The collapse of Majapahit triggered a major migration of Hindu nobles, priests, artists, and artisans to Bali, ushering in a cultural golden age. Bali grew strong enough to dominate Lombok and parts of East Java. But, by the eighteenth century, however, this powerful kingdom had fragmented into nine rival states, ending Bali’s long period of political unity.

Dutch Conquest of Bali

In 1597, a ship full of Dutchmen accidentally landed on Bali. It is said the Europeans fell so deeply in love with the place they stayed for two years, and when it was time to leave some refused to go. Bali at that time was regarded to be at its peak. The king of the island had 200 wives. He traveled around in a chariot pulled by two white buffalo and had at his disposal a retinue of 40 dwarves.

The Dutch seamen were the first Europeans to land in Bali. The Netherlands had no real interest in Bali until the 1800s. In 1846 the Dutch returned with colonization on their minds, having already had vast expanses of Indonesia under their control since the 1700s. Initially on the pretext of punishing the Balinese for plundering shipwrecks, the Dutch sent troops into northern Bali, and involved themselves more and more in the island's internal affairs, imposing direct rule on north and west Bali in 1853. By 1894, they had sided with the Sasak people of Lombok to defeat the Balinese. By 1911, all Balinese principalities were under Dutch control.

The Dutch largely ignored Bali at first because it didn’t have any important tradeable goods, it lacked a good harbor until the mid 19th century and its wasn’t positioned along any major trade routes. In 1855 the first Dutch officials arrived on the island. Over the following decades, often using salvage claims over shipwrecks to enter Balinese territory, the Dutch took more and more control of the island and pushed the Balinese kingdom into the south, where it put up military resistence to colonialism.

Between 1894 and 1908, the Dutch subdued the Balinese kingdoms, first in Lombok and then in southern Bali. Bloody resistance by the royal courts ended with puputan, or suicide charges into Dutch fire (See Below). The Dutch put pressure on the Balinese rulers by siding with their adversaries, the Sasaks of Lombok. In 1906, the Dutch invaded Bali and mounted a naval bombardment of the island after the Balinese refused to pay compensation for ransacking a Chinese ship.

The Dutch ruled Bali through the surviving aristocrats, who became administrators, major landowners, and religious authorities. Colonial legislation solidified caste hierarchies at the expense of rising commoner families. The Dutch enacted a policy called “Baliseering”, or the Balinization of Bali, which was aimed to “protect” the island’s culture from spreading Islam and keeping it traditions alive. Court life on Bali largely died under the Dutch. For some people, the defeat of the Balinese marked the passing of an era. The great Indonesian writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer wrote, “I bowed my head” and “went back to my desk. I took out my diary and wrote these words: ‘Today I begin.’”

Royal Mass Suicide: Puputan Revolts in 1906 and 1908

Puputan is a Balinese term for a collective ritual suicide carried out to avoid the humiliation of surrender. The most famous puputans occurred in 1906 and 1908, during the Dutch conquest of Bali. When it became clear the Balinese royals could no longer hold off the Dutch, they chose to die rather than submit to colonial rule. Under the now legendary “puputan”, the royal family ordered their palaces to be set alight. Then clad in white and armed only with spears they and some of their supporters hurled themselves at the Dutch. Maybe a thousand died. The Dutch gained controlled of the island.

In September 1906, troops of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army landed at Sanur Beach and advanced inland with little resistance. They reached Kesiman, where the local ruler—vassal to the king of Badung—had already been killed by his own priest after refusing to lead an armed resistance. The palace was burning, and the city was deserted. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Dutch then marched toward Denpasar. As they approached the royal palace, they saw smoke rising and heard drums beating inside the walls. A silent procession soon emerged, led by the Raja of Badung, carried on a palanquin. He wore white cremation garments, elaborate jewelry, and carried a ceremonial kris. Behind him followed officials, guards, priests, wives, children, and retainers, all dressed in white and ritually prepared for death.

When the procession halted a short distance from the Dutch troops, the Raja stepped down and signaled a priest, who stabbed him to death. Others immediately killed themselves or one another. Women hurled jewelry and gold coins at the soldiers in defiance. After confusion and scattered attacks with spears and lances, the Dutch opened fire with rifles and artillery. Hundreds, possibly more than a thousand people, were killed as more participants emerged from the palace. The palace of Denpasar was looted and destroyed. Later the same day, a similar puputan occurred at the nearby palace of Pemecutan, where the co-ruler Gusti Gede Ngurah and his followers killed themselves. The Dutch again looted and razed the palace.

These events are remembered as the “Badung Puputan” and are locally honored as acts of resistance against foreign domination. A large monument now stands in central Denpasar on the former site of the royal palace to commemorate this sacrifice. Dutch forces continued their campaign into Tabanan, where the king Gusti Ngurah Agung and his son initially surrendered and attempted to negotiate autonomy. When the Dutch offered only exile, both chose to commit puputan while imprisoned. Their palace was subsequently plundered and destroyed.

The broader conflict began after Balinese resistance to Dutch efforts to impose an opium monopoly. Riots broke out in Klungkung and Gelgel, where a Javanese opium dealer was killed. Dutch troops suppressed the uprisings with force, killing many Balinese and bombarding Klungkung.

The final puputan occurred in April 1908. Dewa Agung Jambe, the Raja of Klungkung, led about 200 followers out of his palace, dressed in white and armed with a legendary kris believed to bring victory. The Raja was shot by Dutch troops, and his six wives immediately killed themselves, followed by the rest of the procession, marking the end of Balinese royal resistance.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Indonesia Tourism website

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026