BALINESE FAMILIES

A Balinese domestic unit is defined as a group that shares meals or use the same kitchen. Extended families are more the rule than nuclear ones. A typical family a husband, wife, children, patrilineal grandparents and unmarried siblings. All members of this family pay a role in child rearing:parents, grandparents, and older siblings. [Source: Ann P. McCauley,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Balinese families bath together in irrigation canals and no one is embarrassed by their nakedness. Balinese women have traditionally not used perfumes. They are very clean and soap is how they perfume. They like woody, floral fragrances. This discovery was made by an employee of the International Flavors and Fragrance who trying to understand why European soap wasn't selling very well in Indonesia. [Source: Boyd Givens, National Geographic, September 1986]

Inheritance follows patrilineal lines. Ideally, property is passed from father to son, but if a man has no sons, he may designate a daughter as heir or allow his property to be divided among his brothers. The family house compound is usually inherited by the child—often the eldest or the youngest—who assumes responsibility for caring for aging parents and any unmarried relatives who remain in the household.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BALINESE: LANGUAGE, CUSTOMS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

BALINESE SOCIETY: GROUPS, CASTE, THE SUBAK SYSTEM factsanddetails.com

LIFE IN BALI: VILLAGES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK, AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com

BALINESE RELIGION: HINDUISM, SPIRITS, TEMPLE LIFE, PRIESTS factsanddetails.com

FUNERALS AND DEATH IN BALI factsanddetails.com

BALINESE CALENDAR factsanddetails.com

BALINESE HOLIDAYS, FESTIVALS, RITUALS, CEREMONIES AND OFFERINGS factsanddetails.com

BALINESE CULTURE AND ARTS factsanddetails.com

BALI: GEOGRAPHY, LIFESTYLE, REPUTATION, GETTING THERE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF BALI: ORIGIN, KINGDOMS, MASS ROYAL SUICIDES factsanddetails.com

MODERN HISTORY OF BALI: VOLCANIC ERUPTIONS, TERRORISM, RECOVERY factsanddetails.com

BALI BOMBING IN 2002 factsanddetails.com

TOURISM IN BALI: CELEBRITIES, RESILIENCE AND ITS RISE FROM A 1930s SOCIALITE ARTIST COLONY factsanddetails.com

NEGATIVE SIDE OF TOURISM IN BALI: OVERDEVELOPMENT, BAD BEHAVIOR DONALD TRUMP factsanddetails.com

Balinese Kinship Groups, Responsibilities and Terms

A kinship group in Bali is described as one that is organized around group of men related through a common ancestor, who worship with other families at a common ancestor temple. The group’s activities revolve around around performing rituals at the temple. Family members are often referred to by their relative age. The Triwangsa clan has many organizations (called "warga") that are spread out all over the island. The senior family (the descendants of the common ancestor) keeps the clan's history and genealogy (babad). [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; Ann P. McCauley,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Balinese society recognizes several levels of kinship, ranging from small household units to broad, inclusive descent groups. At each level, kinship is defined primarily through groups of men described above. These groups are bound by ritual obligations, especially the performance of ceremonies held twice a year at the temple. Every household maintains its own shrine within the house compound, while men who share an inheritance worship at a larger local ancestor temple. These inheritance groups may in turn be incorporated into wider, more loosely defined kin groups that claim descent from a common ancestor, even when genealogical links can no longer be traced. Some families participate only in a small local group, while others see themselves as part of a series of nested kin networks with alliances extending across the island. Such larger kin groups tend to be strongest in times or places marked by social or political factionalism. Kin membership is reckoned patrilineally, though ties through the mother’s line are also remembered and acknowledged.

Balinese kinship terminology follows a Hawaiian, or generational, system. All male relatives the same age as one’s father may also be addressed as “father.” Children are often referred by a name associated with their birth order and adults are called “father of...” The same applies to mothers, siblings, cousins, grandparents, and children. Individuals are also identified by a teknonym (a name applied to a parent based on name of their child) and reflects their gender, caste, and birth order. Children are addressed by this teknonym, while adults are commonly called “father of …” or “mother of …” after the birth of their first child. Elderly people are similarly referred to as “grandfather of …” or “grandmother of …,” emphasizing generational position over personal names.

Balinese Marriages

Although men are allowed to have more than one wife, marriages are generally monogamous. Most couples live with the groom’s parents for some period before establishing a household of their own. Usually, children are part of the groom's family. At least one son must stay home to take care of his parents when they get old. [Source: Ann P. McCauley,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Ideally women should not marry below their caste or kinship group. It is okay for men to do so. It is not acceptable for a husband's sisters and a wife's brothers to be married. In some places there is strong preference for marriages with ancestor-temple groups In other places love matches are the norm as long as they are within certain caste and wealth limits.

Divorce rules vary somewhat but generally a woman who has been married less than three years returns to her father’s home with nothing. If she has been married more than three years and is not adulterous she receives a percentage of what the couple has earned during the period of the marriage. Children of a marriage stay with the father. If a women is chosen by her father as his heir the divorce rules are applied in reverse.

These days, marriages between members of different castes are common. Before Indonesian independence, however, a woman marrying a man of a lower caste would be banished with her spouse from their community.

Balinese Weddings and Elopements

In the wedding ceremony the groom carries a sword. In the old day the bride and the groom lay on a table with their heads hanging over the edge while a priest filed their teeth. Mick Jagger and Jerry Hall were married in a Hindu ceremony in Bali in 1990.

Balinese wedding customs generally follow three main stages. First is a formal ceremony in which the groom’s family asks the bride’s family for her hand in marriage. This is followed by the wedding ceremony itself. The final stage is a formal visit by the newly married couple and the groom’s family to the bride’s family, during which the bride symbolically “asks leave” of her own ancestors. This visit traditionally also marked the delivery of a bride-price, a practice that has largely disappeared among educated Balinese. Marriages arranged through formal proposal involve numerous elaborate rituals and costly feasts, with assistance and contributions from relatives, neighbors, and the banjar (village council). [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

A far less expensive and extremely popular alternative is elopement, known as mamaling, nyogotin, or nganten. In this form of marriage, a young couple spends a night together at a friend’s house, a publicly recognized act that obliges them to marry. The groom’s family then holds a wedding ceremony without inviting the bride’s family, who are expected to show public displeasure even if they privately approved the match. After some time, the groom’s family makes a formal reconciliation visit to the bride’s family, bringing gifts and seeking acceptance of the union. Once this has occurred, the bride’s family may openly acknowledge the marriage.

Today, elopement is the most common form of marriage in Bali, and parents are usually aware of the arrangement in advance. Given that formal ceremonial weddings are often lavish, expensive, and involve priests and temple rituals, many families quietly welcome elopement as a practical way to avoid heavy financial burdens. [Source:“Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Family Life in Bali

Mark Eveleigh of the BBC wrote:, I lived with Nenek’s family for a year around 15 years ago, and am so fond of them that they’ve become my adopted second family. So now, let me take you on a visit to their family home. I’d like to introduce you to a wonderful old woman whose age is indeterminable and whose name is unspeakable. It’s not that she’s at all sensitive about her age. She was born in Bali at a time — perhaps 80-odd years ago — when births were not accurately recorded. Sometime around Indonesian independence in 1945, she was issued with an ID card, but she lost that many years ago and it wasn’t worth getting a replacement since she never strays more than a few hundred meters from her home in Pekutatan, a fishing village on Bali’s remote south-west coast. [Source: Mark Eveleigh, BBC, June 21, 2018]

As we step off the sunlit lane, glowing with bougainvillea and perfumed with the sweet tang of jasmine, the first thing you’ll notice is the guardian shrine that protects the house. The next thing you’ll see will be Nenek, or her daughter-in-law Ketut, emerging from the kitchen with a Balinese sing-song Hindu greeting — “om swastiastu” — and an invitation to have coffee.

Ketut [Nenek’s adopted daughter] will have prepared the food in her old-style dapur (kitchen). Traditional kitchens of this sort are rarely found even in the remotest communities on the island these days. Back when I first lived with the family, Nenek’s grandson Kadek (a dive guide on the reefs off eastern Bali) had recently built a new house for them, right next to the old one. But old habits die hard here, and neither Nenek nor Ketut ever trusted the shiny, tiled kitchen. They gave it a suspicious glance and promptly went back to their customary cooking position, squatting beside a driftwood fire within the slatted bamboo walls of the old dapur. Neither did they sleep in the new house, until, 15 years later, the leaky roof of the old house finally threatened to cave in entirely.

You might still be sipping the coffee when Sudana [Ketut’s husband] himself comes down the steps from the road. Depending on the hour, he’ll either have been cutting grass as fodder for his four pink buffalo or he’ll just have returned homeward along the black-sand beach from the two rice paddies he leases from a local landowner.

Sudana plays in the local Balinese temple orchestra known as the gamelan and practices at least once a week at a neighbour’s home, serenading us late into the evening. If it’s your first visit to his home, Sudana might offer to show you around their small family temple: behind delightfully moss-laden walls adorned with the Hindu swastika stand the various stone shrines that protect the house. Beyond the temple is a little grove of coconut, cacao, banana, papaya and coffee trees, and you might hear the grunt of a pig that is destined to become a ‘guest of honour’ at some forthcoming ceremony, when it’ll be served up as babi guling. Literally meaning ‘turned pig’, babi guling is roasted on a spit over the course of many hours and could be considered the Balinese national dish.

Nenek will sit close while you eat, silently happy to be in company. As a visitor, you’d assume that Nenek is Sudana’s real mother. In all senses apart from the biological one, she is. You see, Nenek never had a son and her only daughter moved to the east of the island when she got married. This meant that when Nenek’s own husband died many years ago, she would have nobody to look after her in her old age. So, with the typical practicality of the Balinese, Sudana’s parents (who had several children) and lived nearby gave him to Nenek to raise as her own. It’s a common system here with no stigma attached, and it continues even today.

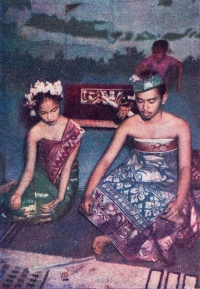

Little Ayu, the baby of the family and at 11 years old one of the village’s most talented traditional dancers, was also given to the family, by her father (Sudana’s brother) when she was still a baby. Ayu’s biological parents were having trouble making ends meet with the children they already had, and Sudana’s sons had already grown and left home. So Ayu now has two sets of parents. She delights in spending time with her biological mother and father (who live in the same street), but it’s clear that Sudana and Ketut’s house is ‘home’ to her.

Balinese Children

Children are treated with great affection. "A baby is the holiest object on earth," wrote John Reader, “an object of sublime innocence, blemished only by the means of its passage into the world. The afterbirth is buried under a stone in the compound (to the right of the entrance if it’s a boy, to the left if it’s a girl), where its becomes a symbol of the four ethereal brother or sisters, one guarding each cardinal direction." [Source: "Man on Earth" by John Reader, Perennial Libraries, Harper and Row]

The Balinese believe that the very young and very old are close to the gods. Infants are not allowed to touch the earth for the first three months of their lives because they are thought to be angels. After 105 days they allowed to touch the ground in a special ceremony in which bracelets and anklets are fastened to their bodies to prevent them from floating upwards again. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York]

Boys are encouraged to energetic and skilled. Girls are taught to be responsible and attractive. The first haircut, first tooth are all celebrated with special rites. Of particular importance is a puberty rite in which an adolescent's evil canine teeth are filed down in preparation for marriage and parenthood.

Balinese Rites of Passage

Depending on a family's caste or wealth, as many as thirteen life-cycle rituals (manusa yadnya) can be performed. These rituals include: the sixth month of pregnancy; birth; the falling off of the umbilical cord; the 12th, 42nd, and 105th days after birth; the 210th day after birth, which marks the child's first "touching of the earth"; the emergence of the first adult tooth; the loss of the last baby tooth; the onset of puberty (first menstruation for girls); tooth filing; marriage; and purification for study. [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Great care is taken to show respect to a newborn infant's "spiritual siblings": the placenta, amniotic fluid, blood, and lamas or banah (a natural yellow salve that covers the skin). The placenta is buried under a river stone at the entrance of the sleeping house. If properly treated, these "four companions" (kanda empat) can protect the child in life, but if neglected, they may harm it.

Balinese are not given their personal name until 105 days after their birth. After seven days bracelets of black string, symbolic of the human duties, are place on them. At 42 days they are given an amulet with a piece of their umbilical chord inside and their ears are pierced. At a 105 days the child is "planted into the earth." Before that time they considered to be more god-like than human.

Tooth filing is performed on teenagers as a necessary prerequisite to adulthood to purge them of their "animal" nature, which is associated with the evils of lust, greed, anger, drunkenness, confusion, and jealousy symbolized by the fang-like upper canines. Full adulthood, in the sense of complete social responsibility, begins only with marriage.

Women and Gender Roles in Bali

Although menstruating women are considered ritually impure and may not enter temples, discrimination against women is not as obvious. However, The division of labor between men and women is pretty sharply defined. Men have traditionally plowed and prepared the fields and took care of animals. They work for the banjar (community organization), prepare food for feasts, play in orchestras, attend cockfights, and drink together in the early evenings. Women join their husbands' castes. Among Brahmana families, the wife of a priest may assume his ritual duties after his death.[Source: Ann P. McCauley,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Women have traditionally kept gardens, cared for pigs, cook, wash clothes, went to the markets to buy and sell things, prepared offerings and ran small shops and snack stores. Women generally take care of raising the children. Men and women together do the planting and harvesting in large groups. Men serve as priests while women make offerings used in rituals.

Balinese wives generally exercise significant economic authority: they retain control over their dowries as well as over both their own and their husbands’ earnings, own their clothing and jewelry, and typically hold rights to the family’s small livestock—an important form of capital. In practice, women manage most household finances. [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

A woman may return to her natal family if her husband abuses her, is impotent, fails to support the household, or takes a second wife (madu) without her consent. If she can persuade a court of her husband’s wrongdoing, she is granted custody of the children. In cases of divorce, a wife is entitled to a share of the assets jointly acquired during the marriage. Conversely, a wife who neglects her duties, commits adultery, or remains childless may be repudiated by her husband only if the marriage was contracted through elopement. If the marriage was formally arranged or approved by both families, repudiation is far more difficult; in such cases, a husband may instead live with another woman while continuing to support his wife. Although inheritance in principle passes through male lines, women may be legally designated as “male” for inheritance purposes, in which case their husbands are correspondingly classified as “female.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Indonesia Tourism website

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026