BALINESE SOCIETY

Balinese society has traditionally been organized around villages that cultivated rice. Individuals belong to families, castes, clans and villages and ritual and religion are often closely associated with the way society functions. Society is kept in line through the concept of shared responsibility: if an individual break any rule their actions reflect negatively not only on themselves but all the groups they belong to.

The complexity of Balinese social organization has provided it with the flexibility to adapt to the pressures of modern life and its requirements for the accumulation, distribution, and mobilization of capital and technological resources. Although the Balinese remain self-consciously “traditional,” they have been neither rigid in that tradition nor resistant to change. Social control is exerted mainly through gossip and group pressure. In some cases, an individual may be fined for not showing up for meetings not participating in group work projects. Poverty is widespread. Large numbers of people are subsistence farmers.

Villages are divided by administrative bodies called a “banjar”. The banjar enforces laws, levies taxes and organizes communal projects, marriages, village festivals and funerals. Most banjars have a gamelan orchestra and a dance troupe and children are recruiting at the age of four as dancers and musicians. Children are required to take part in the banjar youth organization until they marry. When they marry they become full fledged members of a banjar. [Source: "Man on Earth" by John Reader, Perennial Libraries, Harper and Row ]

In addition to the banjar villagers most Balinese also belong to six temple congregations: three in their village and others scattered around the island. The other temples include farming temples, water temples, caste temple and so on. There are over 20,000 temple on Bali. Each village has several dozen.

The Balinese also belong to voluntary organizations such as bicycle-buying groups which collects money from its members and deposits it in a treasury instead of individuals going out and buying bicycles on their own. Anthropologist J.S. Lansing described one such group in which couples were not allowed to get married until they received their bicycles.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BALINESE: LANGUAGE, CUSTOMS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

BALINESE FAMILY: MARRIAGE, WOMEN, RITES OF PASSAGE factsanddetails.com

LIFE IN BALI: VILLAGES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK, AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com

BALINESE RELIGION: HINDUISM, SPIRITS, TEMPLE LIFE, PRIESTS factsanddetails.com

FUNERALS AND DEATH IN BALI factsanddetails.com

BALINESE CALENDAR factsanddetails.com

BALINESE HOLIDAYS, FESTIVALS, RITUALS, CEREMONIES AND OFFERINGS factsanddetails.com

BALINESE CULTURE AND ARTS factsanddetails.com

BALI: GEOGRAPHY, LIFESTYLE, REPUTATION, GETTING THERE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF BALI: ORIGIN, KINGDOMS, MASS ROYAL SUICIDES factsanddetails.com

MODERN HISTORY OF BALI: VOLCANIC ERUPTIONS, TERRORISM, RECOVERY factsanddetails.com

BALI BOMBING IN 2002 factsanddetails.com

TOURISM IN BALI: CELEBRITIES, RESILIENCE AND ITS RISE FROM A 1930s SOCIALITE ARTIST COLONY factsanddetails.com

NEGATIVE SIDE OF TOURISM IN BALI: OVERDEVELOPMENT, BAD BEHAVIOR DONALD TRUMP factsanddetails.com

Balinese Social Groups

Unlike most Javanese, Balinese participate enthusiastically in several interlocking corporate groups beyond the immediate family. One of the most important of these is the dadia, or patrilineal descent group. This is a group of people who claim descent through the male line from a common ancestor. The group maintains a temple to that ancestor, a treasury to support rituals associated with it, and certain chosen leaders. The prestige of a dadia depends in part on how widespread and powerful its members are. However, most of these organized groups tend to be localized, because it is easier to maintain local support for their activities and temple. Balinese prefer to draw spouses from within this group. These corporate kin groups can also be the basis for organizing important economic activities, such as carving cooperatives, gold- and silversmithing cooperatives, painting studios, and dance troupes. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Another important affiliation for Balinese is with the banjar, or village compound, which overlaps with, but is not identical to, the dadia. The banjar and the dadia share responsibility for security, economic cooperation in the tourist trade, and the formation of intervillage alliances. The banjar is a council of household heads and oversees marriage, divorce, and inheritance transactions. In addition, it is the unit for mobilizing resources and labor for the spectacular cremations for which Bali has become increasingly well known. Each banjar may have individual orchestra, dance, and weaving clubs. *

Yet another important corporate group is the agricultural society, or subak, each of which corresponds to a section of wet-rice paddies. Each subak is not only a congregation of members who are jointly responsible for sacrificing at a temple placed in the center of their particular group of paddies, but also a unit that organizes the flow of water, planting, and harvesting. Because 50 or more societies sometimes tap into a common stream of water for the irrigation of their land, complex coordination of planting and harvesting schedules is required. This complexity arises because each subak is independent. Although the government has attempted periodically to take control of the irrigation schedule, these efforts have produced mixed results, leading to a successful movement in the early 1990s to return the authority for the agricultural schedule to the traditional and highly successful interlocking subak arrangement. *

In addition, Balinese form sekaha, voluntary associations organized around specific activities. These may be permanent or temporary and include music, dance, and theater groups, as well as clubs for young men or young women. [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Balinese Caste System

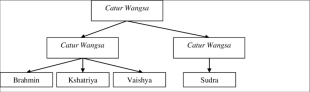

Bali has a Hindu caste system similar to the one in India but it has never been rigidly applied. The Balinese are Hindus, and Hindus practice the caste system. Individuals and kin groups identify themselves as being one four hereditary castes. The “Brahmins” (priests) at the top; then “Ksatriyas” (rulers and warriors) and “Wesia” (traders). Some 90 percent of the Balinese population belongs to the “Sudra” (farmer) caste at the bottom. There are no untouchables on Bali.

The Balinese caste system involves no occupational specializations, except the Brahmin priesthood, or ideas about ritual contamination between the ranks. It does not prohibit marriage between ranks but does forbid women to marry beneath their class. The vast majority of Balinese, including many wealthy entrepreneurs and prominent politicians, belong to the Shudra (commoner-servant) class. [Source: Library of Congress *]

On Bali only the older people still believe in the caste system; the young ignore it. Members of the Brahmin, Ksastyria and Wesia classes preside over some ritual activities and are more likely to head large ancestor temple groups but otherwise there isn’t much difference between them and lower caste people. In Balinese vernacular the individual is "tied" to his position in life and the numerous obligations and duties associated with that position. People appear carry themselves with poise and seem to be in harmony with the people around them as well as their surroundings.

Hinduis has been practiced in Bali since the Majapahit period (1294-1527). The first three groups — Brahmana, Satria, Wesia, and Sudra — are collectively known as the Triwangsa and comprising about 15 percent of the population. They trace their origins to Majapahit nobility and were regarded as privileged “insiders” in the precolonial kingdoms. The Sudra majority were known as jaba, or “outsiders.” Distinct from both groups are the Bali Aga, or Bali Turunan, a small population who claim descent from the island’s pre-Majapahit inhabitants and who have traditionally lived apart in mountain villages. Relations among castes have long been contested. It was only under colonial rule that Brahmana priests were able to assert clear superiority, a claim not universally accepted—for example, by the Pande, a Sudra subcaste of blacksmith origin who take holy water from priests of their own group. [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

See Language and Names Under BALINESE: LANGUAGE, CUSTOMS, BEHAVIOUR factsanddetails.com

Balinese Subak System

Most crops are raised on subaks that are collectively worked but not collective farms. The land is owned by individuals, sometimes from distant villages, who are free to sell the land, work it, or lease if they choose. The owners may consume the rice or sell it and people from all castes may farm or own the land. The Subak System refers to the thousand year old self-governing associations of farmers who share the use of irrigation water for their rice fields. Water from volcanic lakes is diverted through rivers and channels to end up in the rice terraces. In 2012, Bali’s subak system was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Water to irrigate the Balinese rice terraces often times originates from volcanic lakes many kilometers away. Through a complex process water is released to different rice growing areas, known as “subaks”, at different times so that it is utilized efficiently. The irrigation system, consists of tunnels and aqueducts that in some cases were originally built over a 1000 years ago and are still utilized today. [Source: "Man on Earth" by John Reader, Perennial Libraries, Harper and Row =]

The water from the lake may flow from a single canal which in turn is divided in smaller canals that lead to the subaks. There are thousands of subaks, each averaging about 200 acres in size, and the water flowing in and out is regulated by process that has been fine tuned over the centuries. It is sometimes said that the man who runs the subaks is the one with his fields furthest from the water source to make sure that he gives water equitable to everyone and doesn’t leave anyone out. =

The Subak System refers to the thousand year old self-governing associations of farmers who share the use of irrigation water for their rice fields. Water from volcanic lakes is diverted through rivers and channels to end up in the rice terraces. The included areas are: 1) Supreme Water Temple of Pura Ulun Danu Batur; 2) Lake Batur; 3) Subak Landscape of the Pakerisan Watershed; 4) Subak Landscape of Catur Angga Batukaru; and 5) The Royal Water temple of Pura Taman Ayun. [Source: UNESCO]

See Separate Article: NORTH BALI: MT BATUR AND SUBAK WATER TEMPLES factsanddetails.com

Balinese Agricultural Calendar and the Subak System

Balinese farmers do not worry about the technicalities of raising their crop. They simply follow the calendar of “Dewi Sri”, the goddess of rice and fertility. The growing season of 105 days is exactly half of Balinese year of 210 days. The schedule for water openings in the irrigation system is determined by this calendar. The various stages of the growing process—the flooding of the fields, the transplanting of seedlings and the harvesting of the nature crop—are all determined by the calendar and marked by festivals and rites.

The growing season begins with a festival marking "the Opening of Openings." The water flows down hill in stages over the following months with those near the top planting first. When the water is released before harvesting it fills the terraces of another farmer who is just getting ready to plant. Individual subaks are worked in a similar fashions: the upper terraces are cultivated first and the water drained from them is used in the lower terraces. [Source: "Man on Earth" by John Reader, Perennial Libraries, Harper and Row =]

In the 1970s foreign aid workers persuaded the Balinese to speed up the rice growing process by adding fertilizer. The result an was increase in the number of rice-eating mice who usually starved and died out during the fallow periods and an increase in the number of malaria mosquitos. The soil became harder and more difficult to till. Productivity increased at first but later dropped and the old system was revived. =

Subak System as a Manifestation of the Tri Hita Karana Philosophy

The cultural landscape of Bali consists of five rice terraces and their water temples that cover 19,500 ha. The temples are the focus of a cooperative water management system of canals and weirs, known as subak, that dates back to the 9th century. Included in the landscape is the 18th-century Royal Water Temple of Pura Taman Ayun, the largest and most impressive architectural edifice of its type on the island. The subak reflects the philosophical concept of Tri Hita Karana, which brings together the realms of the spirit, the human world and nature. This philosophy was born of the cultural exchange between Bali and India over the past 2,000 years and has shaped the landscape of Bali. The subak system of democratic and egalitarian farming practices has enabled the Balinese to become the most prolific rice growers in the archipelago despite the challenge of supporting a dense population. [Source: UNESCO]

A line of volcanoes dominate the landscape of Bali and have provided it with fertile soil which, combined with a wet tropical climate, make it an ideal place for crop cultivation. Water from the rivers has been channelled into canals to irrigate the land, allowing the cultivation of rice on both flat land and mountain terraces.

Rice, the water that sustains it, and subak , the cooperative social system that controls the water, have together shaped the landscape over the past thousand years and are an integral part of religious life. Rice is seen as the gift of god, and the subak system is part of temple culture. Water from springs and canals flows through the temples and out onto the rice paddy fields. Water temples are the focus of a cooperative management of water resource by a group of subaks. Since the 11th century the water temple networks have managed the ecology of rice terraces at the scale of whole watersheds. They provide a unique response to the challenge of supporting a dense population on a rugged volcanic island.

The overall subak system exemplifies the Balinese philosophical principle of T ri Hita Karana that draws together the realms of the spirit, the human world and nature. Water temple rituals promote a harmonious relationship between people and their environment through the active engagement of people with ritual concepts that emphasise dependence on the life-sustaining forces of the natural world.

In total Bali has about 1,200 water collectives and between 50 and 400 farmers manage the water supply from one source of water. The property consists of five sites that exemplify the interconnected natural, religious, and cultural components of the traditional su b ak system, where the subak system is still fully functioning, where farmers still grow traditional Balinese rice without the aid of fertilisers or pesticides, and where the landscapes overall are seen to have sacred connotations.

The sites are the Supreme Water Temple of Pura Ulun Danu Batur on the edge of Lake Batur whose crater lake is regarded as the ultimate origin of every spring and river, the Subak Landscape of the Pakerisan Watershed the oldest known irrigation system in Bali, the Subak Landscape of Catur Angga Batukaru with terraces mentioned in a 10th century inscription making them amongst the oldest in Bali and prime examples of Classical Balinese temple architecture, and the Royal Water temple of Pura Taman Ayun, the largest and most architecturally distinguished regional water temple, exemplifying the fullest expansion of the subak system under the largest Balinese kingdom of the 19th century.

Subak components are the forests that protect the water supply, terraced paddy landscape, rice fields connected by a system of canals, tunnels and weirs, villages, and temples of varying size and importance that mark either the source of water or its passage through the temple on its way downhill to irrigate subak land.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Indonesia Tourism website

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026