BALINESE PEOPLE

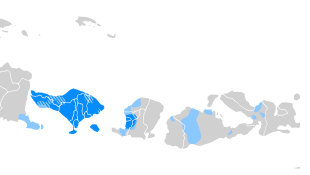

There is probably no group in Indonesia more conscious of its own ethnic identity than the Balinese. Inhabitants of the islands of Bali and Lombok and the western half of Sumbawa, Balinese are often portrayed as a graceful, poised, and aesthetically inclined people. Although such descriptions date back six centuries or more and are at least partially based on legend, this characterization is also partly based on the realities in contemporary Indonesia. Virtually no part of Bali has escaped the gaze of tourists, who come in increasing numbers each year to enjoy the island’s beautiful beaches and stately temples and to seek out an “authentic” experience of its “traditional” culture. The market for “traditional” carvings, dance performances, and paintings has boomed, and many Balinese successfully reinvest their earnings in further development of these highly profitable art forms. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Balinese have a long history of contrasting themselves profitably with outsiders. The contemporary distinctive Hindu religious practices of the Balinese date back at least to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when Javanese princes from Majapahit fled the advances of Islam and sought refuge in Bali, where they were absorbed into the local culture. Since that time, Balinese, with the exception of a minority of Muslims in the north, have maintained great pride in their own distinctiveness from the surrounding Muslim cultures. Since the terrorist bombing of two nightclubs in the Balinese beach town of Kuta in 2002 by Muslim extremists, tensions between Balinese and non-Balinese Muslims have increased. *

Books: “Island of Bali” by Miguel Covarrubias (1937) is regarded as the classic from the period when Bali was discovered by the rich and famous. There are multitude of other books, many of them dealing with Balinese arts and culture. Margaret Mead spent some time in Bali in the 1930s. She learned the language, listened to folk tales and myths and wrote a book called “Balinese Character” with her husband Gregory Bateson.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BALINESE SOCIETY: GROUPS, CASTE, THE SUBAK SYSTEM factsanddetails.com

BALINESE FAMILY: MARRIAGE, WOMEN, RITES OF PASSAGE factsanddetails.com

LIFE IN BALI: VILLAGES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK, AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com

BALINESE RELIGION: HINDUISM, SPIRITS, TEMPLE LIFE, PRIESTS factsanddetails.com

FUNERALS AND DEATH IN BALI factsanddetails.com

BALINESE CALENDAR factsanddetails.com

BALINESE HOLIDAYS, FESTIVALS, RITUALS, CEREMONIES AND OFFERINGS factsanddetails.com

BALINESE CULTURE AND ARTS factsanddetails.com

BALI: GEOGRAPHY, LIFESTYLE, REPUTATION, GETTING THERE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF BALI: ORIGIN, KINGDOMS, MASS ROYAL SUICIDES factsanddetails.com

MODERN HISTORY OF BALI: VOLCANIC ERUPTIONS, TERRORISM, RECOVERY factsanddetails.com

TOURISM IN BALI: CELEBRITIES, RESILIENCE AND ITS RISE FROM A 1930s SOCIALITE ARTIST COLONY factsanddetails.com

NEGATIVE SIDE OF TOURISM IN BALI: OVERDEVELOPMENT, BAD BEHAVIOR DONALD TRUMP factsanddetails.com

Balinese Language and Unspeakable Names

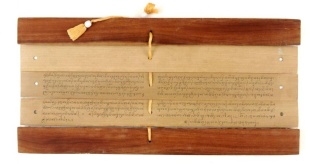

The Balinese language is an Austronesian language belonging to the Malayo-Javanic subgroup. It is similar to Javanese and has been influenced by the Indian languages that influenced Javanese. Balinese script is derived from the Palava writing system of southern India. The earliest inscriptions found in Bali, dating back to he A.D. 8th century are in both Sanskrit and Old Balinese. Although Balinese now increasingly use Latin letters, their traditional script was a distinct version of the Javanese alphabet, which in turn was derived from the Pallava writing systems of southern India

Although Balinese is phonologically similar to the languages of eastern Indonesia — such as Sasak, the language of Lombok — Java to the west has had a stronger linguistic and literary influence. Balinese has levels of speech that require speakers to adjust their vocabulary based on their relative caste position, their feelings about the person they are speaking to and the subject matter.

All Balinese have one of four special names that refers to whether they are the oldest son or daughter, the second oldest, third oldest and forth. The fifth oldest has the same name as the first oldest and so on. Adults are commonly referred to through kinship terms that relate them to a child or grandchild, such as “Father (Pan) of X,” “Mother (Men) of Y,” or “Grandfather (Kak) of Z.” In addition, personal names traditionally reflect birth order. In Sudra families, the first-born is named Wayan, the second Made, the third Nyoman, the fourth Ketut, and the fifth Putu. Higher castes add specific titles: Wesya use Gusti for men and Gusti Ayu or Ida/Ni for women; Satrya use Dewa for men and Dewa Ayu or Agung Gede for women; and Brahmana use Ida Bagus for men and Ida Ayu for women. [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Mark Eveleigh of the BBC wrote: I’d like to introduce you to a wonderful old woman whose age is indeterminable and whose name is unspeakable She’s not deliberately mysterious about her name either. These days, the entire community calls her simply Nenek (grandmother). I’m not superstitious at all, but my long familiarity with Balinese customs means that even I would shudder to use her name. You see, the gods are said to have a list of people who are due to be summoned into the afterlife, and to speak Nenek’s name aloud could alert them to the presence of someone who’s been overlooked. [Source: Mark Eveleigh, BBC, June 21, 2018]

In a country where the unifying language of Bahasa Indonesia is spoken by almost the entire population, Nenek is one of only a few remaining people who can only communicate in a regional language (in her case Balinese). While my Indonesian is more than sufficient for conversation with the rest of Nenek’s brood, I’ve never learned more than a smattering of the local Balinese. The fact that, in recent years, Nenek has become increasingly hard of hearing has further stymied our attempts at communication. Lately, however, I’ve been charmed to notice that Nenek seems content to communicate more and more with hugs and simple, silent hand-holding.

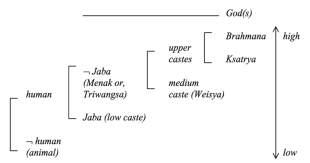

Caste and Different Forms of the Balinese Language

Balinese has a different set of vocabularies and levels of speech depending on the caste of the people being spoken to. Traditionally, there were five forms of the language but today generally only three are used: 1) Low Balinese (rendah) or Ordinary (biasa) used by equals or when talking to inferiors; 2) Middle Balinese (madia) or Refined (halus) used for addressing or speaking about superiors or strangers; and 3) High Balinese (tinggi) when talking to superiors, especially in situations in which religion is addressed. The levels are most complicated when speaking about the body. There are nine different vocabulary lexicons. The Balinese spoken in Balinese theater is even more complicated, including old Balinese and Sanskrit. [Source: "Man on Earth" by John Reader, Perennial Libraries, Harper and Row]

Balinese people are often tongued tied until they know the position of the person they are speaking to. The traditional Balinese greeting is "Where do you sit?" which is another way of asking what a person's social position is. A person of low caste speaking to someone in a higher caste speaks in higher Balinese. The higher caste person speaks to the lower caste person in Low Balinese. Equals speak Middle Balinese to each other.

Today, the High (tinggi) level of Balinese is used almost exclusively when speaking to Brahmana priests. In most families, only one person is fluent in it, and that individual usually represents the household in formal requests to priests. The Refined (alus) level is used when addressing people of higher status, elders, and one’s parents. The Low level (rendah), also known as Ordinary (biasa) or Coarse (kasar), is used for speaking with those of equal or lower status, including children, close relatives, intimate friends, and household staff; men traditionally use this level when speaking to their wives. When a person’s status is unknown, speakers often combine Refined and Ordinary forms. The Middle (madia) level is used with people of equal status who are not close. When two Balinese meet for the first time, they usually begin in the Middle level and adjust their speech once relative status becomes clear. [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Although this system of linguistic etiquette remains strictly observed in religious rituals and customary settings, its use in everyday life has weakened. Higher-caste speakers increasingly use the Refined level when addressing lower-caste individuals who hold senior positions in the national bureaucracy. Classmates often speak in the Ordinary level regardless of caste. In schools in Denpasar, teachers typically address students in the Middle level, while in more conservative parts of eastern Bali the Refined level is still used, including in first encounters between strangers. Like in Java, the national language, Bahasa Indonesia, provides a neutral alternative that allows speakers to avoid positioning themselves within the traditional caste hierarchy, even if modern social distinctions remain.

Bali Population and Demography

Bali is home to about 4.4 million people. About 95 percent are Balinese. The other five percent are Chinese, Muslims and other minorities. About 80 percent of the island's population live in the southern part of the Bali. Much of the western part of Bali is uninhabited jungle, where tigers lived until the 1940s. In 1989, Bali’s population was around 2.8 million. At that time the annual population growth rate was 1.75 percent, and Denpasar, the provincial capital, had a population of 260.000 (compared to around 730,000 in 2023). By 2000, Bali’s population was reported to have increased to approximately 3.2 million. [Source: Ann P. McCauley, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Bali is slightly larger than the U.S. state of Delaware, yet its population is roughly four times greater. In 2005, population density reached about 601 people per square kilometer—three times that of neighboring West Nusa Tenggara, more than six times that of East Nusa Tenggara, and about 79 percent of the density of East Java. [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Historically, the Balinese were neither a seafaring people nor, prior to the 20th century, significant migrants (with the exception of western Lombok). Population pressure, however, led many Balinese to join government-sponsored transmigration programs to South Sumatra, Central Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Nusa Tenggara. As a result, Balinese today make up about 3 percent of the population of West Nusa Tenggara Province. At the same time, Bali has attracted migrants from other islands—especially Java—and approximately 11 percent of Bali’s population is ethnically non-Balinese.

Balinese Character

The Balinese are known for their positive disposition. When the write Jamie James gave his condolences to a friend whose four-month-pregnant sister had just died, the man said, "It was God's will. Good-bye, sir. Please gave a happy life.” One person with a lot of experience in Bali said the “Balinese are very friendly, but when there is pressure the will fight back.”

It can be argued that Balinese are among the world’s most patient, tolerance, easygoing and enduring people. Bali’s predominantly Hindu population has managed to survive for centuries with the world’s largest Muslim-majority nation and more recently they have maintained a stiff upper lip in the face of mass tourism, overdevelopment and loutish tourists. But not everything about the Balinese is peace, love and understanding. They are very found of cockfighting and killing chickens and sea turtles is a big part of their ritual and culinary culture.

The Balinese generally go out of their way to avoid conflict. If two individuals are involved in a quarrel or feud they try to avoid each their. “Ramé” is an important Balinese concept. It connotes abundance, fun and excitement in a busy, crowded way. Balinese are also very sociable. Unlike foreign tourist who like to take photographs of natural sights such as a waterfall, the Balinese like to make an offering of fruit and flowers to the waterfall and then photograph their friends playing in the water.

Anjan Chakraborty wrote in The Statesman: Ritualised states of self-control (or lack thereof) are a notable feature of religious expression among Balinese,people, who for this reason have become famous for their graceful and decorous behaviour. An important ceremony at a village temple, for instance, features a special performance of a dance-drama (a battle between the mythical characters Rangda, the witch—representing evil—and Barong, the lion or dragon— representing good), in which performers go into a trance and attempt to stab themselves with sharp knives. Rituals connected with life cycle are also important occasions for religious expression and artistic display. Ceremonies at puberty, marriage and, most notably, cremation, provide opportunities to communicate ideas about community, status and afterlife. [Source: Anjan Chakraborty The Statesman, October 2008]

Balinese Customs

Individuals Balinese are not regularly addressed by their personal name but rather by the name that denotes their birth order. The oldest is referred to Wayan and the second oldest is Njoman. The prefix "Ni" means girl, thus making the oldest girl "Niwayan. The children's parent and grandparents are referred to as "Mother of Wayan" or "Grandfather of Ninjoman" instead of by their personal names.

The axis between the mountains and the sea dominates the Balinese sense of orientation. For example, tradition dictates that one should sleep with one's head facing kaja (the direction of the divine mountains) and one's feet facing kelod (the direction of the demonic sea). The soles of the feet should never face a person who deserves respect (in this case, the mountains). Depending on the location, kaja can mean "north" or "south."[Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

It is not unusual to see a Balinese man with a very long pinky fingernail, that is filed, and sometimes seven or eight centimeters long. The fingernail shows the world that the man doesn't perform manual labor. The reasoning goes, if he did the nail would break. It shows the man is a member of an upper caste and only works for the gods. [Source: Donna Grosvenor, National Geographic, November 1969]

Traditional etiquette, now increasingly confined to ceremonial contexts, emphasizes hierarchy and spatial symbolism. People of higher status or greater age sit in physically higher places and closer to the kaja direction (toward the mountains) and the east. Brahmana priests are greeted with “Ohm Swastiastu,” accompanied by a slight bow and palms pressed together at the chest, a greeting now promoted as a Hindu equivalent to the Muslim “Assalamu alaikum.” In conversation with higher-status individuals, one bows; with children or lower-status people, a nod suffices. Advice or criticism is accepted with a deferential “nggih” (“yes”) or in silence, without contradiction, and every effort is made to comply with requests or commands. [Source: A. J. Abalahin,“Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Children are corrected indirectly. For example, a mother may tell a child that she herself will be scolded if the child misbehaves, or describe misconduct as “low-caste” behavior. High-caste wives avoid correcting elders directly, either allowing them to act as they wish or appealing to an older intermediary such as a mother-in-law. Polite conversation requires self-deprecation, with speakers referring humbly to their own person, possessions, or achievements.

Interactions between unmarried adolescents of the opposite sex are tightly circumscribed; casual conversation is acceptable only in public settings such as food stalls and in the presence of others. Although Balinese culture allows open joking about sex, great care is taken to keep the genitals covered and to ensure that clothing that has been in contact with them—especially garments worn by menstruating women—is stored in places where it will not be positioned above people’s heads.

Balinese Versus Outsiders and Backpackers

Sara Webb of Reuters wrote: “The proportion of Hindus in Bali fell to 87 percent in 2000, from 93 percent in 1995, Suryani said, as Indonesians from densely populated and mainly Muslim Java flocked to Bali in search of work following the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis. In Bali's capital Denpasar, the proportion of Hindus may be closer to 60 percent and in certain districts it is only one in six, she said. The issue of Balinese versus outsiders is likely to be a hot topic in next year's election for governor. "Balinese only have one or two kids because family planning here is very strong" due to pressures from the local banjar, or neighbourhood associations, she said. "But imagine, if Balinese have only one or two kids but people from outside have four, five or six, in a few years the composition will change." [Source: Sara Webb, Reuters, December 12, 2007 ^*^]

“Besieged by outsiders, some Balinese are becoming more aware of the need to preserve their identity. Instead of using Indonesia's unifying language bahasa Indonesia, which is similar to Malay, some Balinese want the Balinese language, steeped in Sanskrit and Javanese with a feudal emphasis on the caste of the person being addressed, to be used more widely.

Once famous for its warring princes and slave-trading, Bali's potential as a tropical tourist destination was exploited by the Dutch colonial rulers and, post-independence, by the Indonesian government. It became part of the hippie and backpacker trail, and attracted more tourists than any other part of Indonesia.

When Islamic militants blew up two bars in Kuta, a popular tourist strip, in 2002 killing more than 200 people, it dealt a severe blow to Bali's tourist industry and put Bali's open welcome and tolerance to the test. "After the bombs, Balinese became aware that it's very dangerous to receive people from outside and we don't know who they are," said Suryani.

But even before 2002, some Balinese had mixed feelings about tourism and development. Some complain that developers destroy local shrines or do not treat temples with sufficient respect. The big, foreign-owned hotels and restaurants often prefer to hire other Indonesians because Balinese, who are bound by their community ties, are obliged to attend important ceremonies and events in their villages and so have to take more time off work.

And some of those who sold their land feel they were forced to give it up, or cheated of a good price. Without their land, many have given up their farming existence and have become dependent on tourism which sometimes turn locals and their unique culture into curios."To compete in the tourism business is about selling themselves, their image, their creativity, they have to sell themselves as tourist objects," said Ida Ayu Agung Mas. As a senator, she frequently hears complaints from Balinese about the consequences of development, ranging from pollution and higher living costs to a shortage of natural building materials as more people move to the island. "Everyone is using the image of Bali, but they must pay back to the community. The Europeans, Chinese, Javanese, they don't give back," she said.

Do Foreign Female Tourists Seek Kuta Cowboys?

Reporting from Bali, John M. Glionna wrote in in the Los Angeles Times, “Amit Virmani was vacationing at Bali's famous Kuta Beach when he met a 12-year-old boy who told him of his unlikely goal: to grow up fast, so he could be a gigolo. The boy said his heroes were the young bronzed Indonesian surfers who provided erotic services to Japanese women and other female tourists who flock to the island for discreet sex vacations. The young men's apparent sexual prowess and serial romances have earned them the nickname "Kuta cowboys." [Source:John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, July 1, 2010 |=|]

“For two years, working alone, Virmani wandered Kuta Beach shooting video for his documentary "Cowboys in Paradise." Surfers detailed their techniques, pick-up lines and strategies to meet and seduce mostly older foreign women. The film, he said, captures the subtle dance between the smiling, mostly longhaired working-class men and often-wealthy female tourists without placing blame. "These cowboys are not prostitutes," but a vital part of the local economy, he said. "They're men with day jobs who meet foreign women and find inventive ways to collect." |=|

“Virmani said the film was not intended as an expose, because the Kuta cowboys had long been tolerated at the beach, a female tourist sex destination for decades. "The cowboys have blurred the lines of seduction, offering the illusion they're in love and not carrying on some cheap sexual affair," he said. "And some women will pay a lot to keep that illusion going." Some cowboys are single and carefree, and admit having unprotected sex. Others are married and have a hard time providing for their families. |=|

“In the film, nearly a dozen men speak candidly about their charm offensive, offering a variety of pickup lines as the camera shows surfers flirting with women, getting backrubs on the beach, couples running in the sand holding hands. One cowboy removes the sunglasses of a woman, singing, "When you take off your sunglasses, I can look into yours eyes," making her laugh. Another man says: "First and foremost, I sell love," adding that he looks for older women with higher salaries. |=|

“Virmani also interviewed some of the tourists, one of whom defends the men. "I don't think they're gigolos. They just like women. There's nothing wrong with that," she said. Approaching the women on the beach, the cowboys arrange dates at dance clubs. They refer to their romantic pursuit as "fishing" and text-messaging lovers as "work." One surfer says women must shower him with gifts for him to stick around, but insists that cowboys never ask for compensation. Some cowboys become emotionally attached to the women and will even marry them, he says. "I am not a gigolo," says one in the documentary. "The gigolos don't speak from the heart. They speak from the mind. But I speak from the heart." |=|

“Nowadays, just the mention of the phrase "Kuta cowboy" can make the easygoing men in their 20s and 30s who rent surf and boogie boards along the tree-lined beach bristle with anger. "It's a big lie; these guys don't exist," said I. Made Subali, a deeply tanned man with skull tattoos who rents surfboards near a sign that encourages clients to "Make New Friends with the Local Boys." He alleged that Virmani misrepresented himself to the surfing community. He said the men didn't know Virmani was making a film and told him tall tales. Now those featured in the documentary are seen as troublemakers in local bars, he said, and several have left the island. |=|

The 83-minute film, with a trailer that has drawn hundreds of thousands of hits on YouTube, has put officials on the defensive. "It portrays Kuta Beach as a sex playground," said Gusti Tresna, who heads the beach security force. "We can't deny it happens. But if women come for a holiday and they hook up with a local guy, fall in love and decide to buy him a motorcycle or even a house — and I've seen it happen — what can the government do?" Virmani said he was surprised by Bali's harsh response. "They shouldn't go arresting people because they're tanned and muscular," he said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Indonesia Tourism website

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026