BALI AFTER INDONESIAN INDEPENDENCE IN THE 1940s

After World War I, a sense of Indonesian Nationalism began to grow. World War II brought the Japanese, who expelled the Dutch and occupied Indonesia from 1942 until 1945. The Japanese were later defeated, and the Dutch returned to attempt to regain control of Bali and Indonesia. However, in 1945, Indonesia was declared independent by its very first president, Sukarno. The Dutch government ceded, and Indonesia was officially recognized as an independent country in 1949.

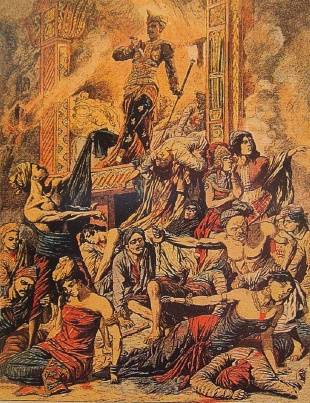

After the Japanese occupation of Bali in World War II, there was fighting between those who supported Indonesian independence and those who favored a continuation of Dutch colonial rule. After Indonesia gained independence from the Dutch in 1950, competition over land on the overpopulated island intensified. One Balinese resistance movement, in the tradition of “pupatan” chose to be wiped out rather than surrender at the Battle of Margarana. Bali’s airport, Ngurah Rai, Is named after the group’s leader.

The 1960s was a tragic time in Bali. The island’s main volcano, the sacred Gunung Agung, erupted and caused great damage, while famine and bloody political upheavals killed thousands of Balinese. The penetration of rival nationwide political networks into Balinese rural society also intensified social conflicts, culminating in the anticommunist massacres of 1965–66 that claimed 100,000 lives and annihilated entire villages. *

Historically, the Balinese were neither a seafaring people nor, prior to the 20th century, significant migrants (with the exception of western Lombok). Population pressure, however, led many Balinese to join government-sponsored transmigration programs to South Sumatra, Central Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Nusa Tenggara. As a result, Balinese today make up about 3 percent of the population of West Nusa Tenggara Province. At the same time, Bali has attracted migrants from other islands—especially Java—and approximately 11 percent of Bali’s population is ethnically non-Balinese. Economy- and nation-building programs pursued by the Suharto government throughout Indonesia —including the Green Revolution and the institutionalization of religion—have had an impact on Bali and as have industrialization and urbanization.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BALI: GEOGRAPHY, LIFESTYLE, REPUTATION, GETTING THERE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF BALI: ORIGIN, KINGDOMS, MASS ROYAL SUICIDES factsanddetails.com

BALI BOMBING IN 2002 factsanddetails.com

TOURISM IN BALI: CELEBRITIES, RESILIENCE AND ITS RISE FROM A 1930s SOCIALITE ARTIST COLONY factsanddetails.com

NEGATIVE SIDE OF TOURISM IN BALI: OVERDEVELOPMENT, BAD BEHAVIOR DONALD TRUMP factsanddetails.com

BALINESE: LANGUAGE, CUSTOMS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

BALINESE SOCIETY: GROUPS, CASTE, THE SUBAK SYSTEM factsanddetails.com

BALINESE FAMILY: MARRIAGE, WOMEN, RITES OF PASSAGE factsanddetails.com

LIFE IN BALI: VILLAGES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK, AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com

BALINESE RELIGION: HINDUISM, SPIRITS, TEMPLE LIFE, PRIESTS factsanddetails.com

FUNERALS AND DEATH IN BALI factsanddetails.com

BALINESE CALENDAR factsanddetails.com

BALINESE HOLIDAYS, FESTIVALS, RITUALS, CEREMONIES AND OFFERINGS factsanddetails.com

BALINESE CULTURE AND ARTS factsanddetails.com

Bali Volcano Eruption

On March 16th, 1963 Bali’s Gunung Agung erupted for the first time in 120 years, with a follow up eruption in May, destroying much of northeastern Bali and killing 1,100 people and leaving 100,000 other homeless. Entire villages were destroyed by layers of ash and flows of hot mud that made it all the way to the sea. Hard rains after the eruption exacerbated the problems, creating landslides and lahars. Roads were closed off, villages were swept away and more people suffered, this time from lack of food. [Source: Windsor Booth, National Geographic, September 1963]

The Balinese call Mount Agung the "navel of the world." They regard it as the center of their universe. During the eruption a gate built to honor president Sukarno was destroyed. This was seen as a symbol of corruption in the government, which was soon ousted. Many Balinese believed that Sukarno caused the eruption by forcing religious leaders in Bali to “stage” an important ritual at a tourism conference.

Some 200 people died when a pyroclastic flow (an incandescent cloud of volcanic debris) raced down the mountain through the in the town of Subagan. Nearly all the inhabitants of the village of Lebih were burnt to death or suffocated by clouds of hot gas. Boiling mud and ash obliterated other towns, where children made strange wailing sounds as they choked to death. Some areas strewn with dog eaten bodies were still too hot to enter weeks after the eruption. Days became night as far away as Java when clouds of cinder and ash blew over and drinking water was in short in supply as rivers and streams became a silty grey mess.

Besakih, Bali's most sacred shrine is located right beneath the volcano. Even though there were dangers of new eruptions and the Governor of Bali forbade people from visiting the temple, thousands went anyway to celebrate an April full moon ceremony. Offerings to the gods included plaited palm fonds, bowls of rice, fried cakes, barbecued fowl, squat bananas and spiny durians. Some ceremonies are climaxed with women picking up burning coals in their bare hands.

After the eruption many Balinese moved to other parts of Indonesia. Two leaders and hundreds were killed during the anti-Communist purge after the 1965 failed coup. Many Balinese were involved in the killing as Communism was viewed as a threat to the traditional Balinese way of life.

Growth of Tourism in Bali

Bali was first promoted to Western travelers as a tropical paradise in the 1930s, when it was part of the Dutch colonial empire. Mass tourism began after the opening of an international airport in the late 1960s and expanded rapidly under Suharto’s New Order government, which viewed tourism revenue as vital to national development. To limit cultural disruption, large hotels were concentrated in the island’s southern peninsula, though budget tourism spread beyond official zones and domestic tourism grew strongly among Indonesian urban middle classes.

Tourism surged from the 1970s through the 1990s, reshaping Bali’s economy and infrastructure, but profits often flowed to non-Balinese elites and the central government. Growth slowed only with the Asian financial crisis and the 2002 Bali bombing. Recovery was swift, however, and by the late 2000s Bali had fully rebounded, with a shift toward high-end tourism, expanded air connections, and rapid growth in luxury resorts and services.

Despite these changes, Balinese culture has not disappeared. It continues to adapt and thrive, shaped more by internal social dynamics than by tourism alone. Everyday religious practices persist, even as modern work demands alter how traditions are carried out, highlighting the ongoing balance between economic life and cultural obligations.

See Separate Article: DEVELOPMENT OF BALI AS AN ARTIST COLONY AND TOURISM CENTER factsanddetails.com

Bali Bombing in 2002

Bali bombing site October 12, 2002 a bombing on the Indonesian holiday island of Bali killed 202 people, 88 of them Australians, and injured more than 160, many of them suffering from terrible burns. The attack took place at Kuta Beach, a popular resort with foreign tourist in Bali. It was the worst terrorist attack since the September 11th attacks and brought Indonesia to the forefront of the war on terrorism. The attacks are carried out by Jemaah Islamiyah, a South-east Asian extremist group inspired by Al Qaida.

Two bombs went off almost simultaneously. The first went off at Paddy’s Irish Pub. It killed eight people and was carried in the a vest of a suicide bomber. The main bomb went off seconds later in front of the Sari Club on Jalan Legian, the main street in Kuta. A third bomb went of at the U.S. consular offices but didn’t cause any casualties.

The main bomb was made of one-ton of ammonium nitrate fertilizer, potassium chloride and other chemicals and at least 50 kilograms of chlorate explosives. These were placed inside filing cabinets in a white van parked by a suicide bomber in front of the Sari Club. Powerful enough to leave behind a crater in the street, the bomb was set off “booster charge” of a TNT-like explosive activated with a cell phone. The bomb explosion set off secondary blasts caused by exploding gas cylinders in the club causing the flimsy roof of the club to collapse, trapping hundreds inside. Fires spread to adjacent buildings, some of which had their roofs blown off and walls smashed by the blast.

See Separate Article: BALI BOMBING IN 2002 factsanddetails.com

Bali After the Bali Bombing

Tourism, the backbone of Bali’s economy, initially collapsed after the 2002 Bali bombing. Shops closed, hotels laid off workers, and airlines reduced flights before stopping service altogether. “The whole of Bali emptied out,” Jamal Hussain, general manager of the Hard Rock Hotel Bali told the New York Times. The situation worsened when SARS struck Asia the following year, followed by terrorist attacks in Jakarta, including bombings at a Marriott hotel and the Australian Embassy. Both attacks were linked to Jemaah Islamiyah, the same group suspected in the Bali bombings. [Source: Denny Lee, New York Times, March 27, 2005 ]

The threat of terrorism became a constant presence. Resorts and public places introduced heavy security: armed guards, vehicle checks, bomb-sniffing dogs, and metal detectors. Police patrols increased during holidays, while Australia, Britain, New Zealand, and the United States repeatedly issued travel warnings. After two years of economic decline, aggressive street selling reflected the island’s desperation.

Despite these setbacks, Bali began to recover. About two and a half years after the bombings, new hotels opened across the island, signaling renewed confidence. Major international brands invested in luxury resorts, from large beachfront hotels in Nusa Dua to boutique properties in Ubud and Seminyak. According to the Bali Hotels Association, these developments showed continued optimism about Bali’s future.

Tourism numbers rebounded strongly. In 2004, nearly 1.5 million visitors came to Bali, a 47 percent increase from the previous year. American arrivals also rose sharply. Beaches were once again crowded, traffic jams returned near the airport, and hotels that had nearly closed were fully booked. Occupancy rates jumped from around 25 percent to as high as 75 percent in some resorts.

Bali’s recovery also brought a shift toward high-end tourism. Luxury hotels, upscale restaurants, spas, and nightlife venues expanded rapidly. New airline routes opened, reconnecting Bali with Australia, Japan, and South Korea. Tourism experts noted that while terrorist attacks can cause short-term damage, destinations often recover quickly. Compared with other cities affected by terrorism, Bali’s rebound was swift, and a full recovery had occurred by the late 2000s.

The rise of Islamism in Indonesia, though restrained by moderate Muslim, secular, and Christian counterpressure, has caused concern for the Balinese. An "anti-pornography" bill was viewed as potentially threatening traditional Balinese religious art.

Bali Royalty Today

Various royal families (like the Ubud and Klungkung dynasties) maintain traditional roles in Bali today, with figures like Tjokorda Raka Kerthyasa (Ubud) and Arya Wedakarna holding significant cultural influence, acting as community leaders and protectors of Balinese customs rather than political rulers. These "kings" (Tjokorda/Raja) lead customary villages (Desa Adat) and represent historical lineages, but their authority is cultural, not governmental. [Source: Google AI]

Tjokorda Raka Kerthyasa carries his royal heritage lightly. Born into Ubud’s royal family, his lineage traces back to the Majapahit Empire, a tradition that effectively ended when Dutch colonization reduced the kingdoms to administrative regions. Known simply as Pak Cok, he lives as an ordinary citizen—witty, thoughtful, deeply spiritual, and direct when necessary—qualities he believes define good leadership in any system. [Source: Trisha Sertori, Jakarta Post, January 30, 2009]

Cok has no interest in restoring the monarchy. For him, returning to the past is a “dangerous fantasy,” except as a source of lessons. He believes the current system suits the present because it serves the people. His sense of responsibility is expressed through public service and cultural work: he is active in politics and religious life and serves as president of the Bali Heritage Trust, patron of the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival, and a Rotarian. As he explains, being born into a palace means accepting social obligations—especially preserving, sustaining, and renewing both the material and spiritual culture of society. Respect, he says, comes not from titles, but from actions.

Early in life, Cok stepped beyond traditional expectations by marrying an Australian woman, Asri, in 1978. Although this initially surprised his family, she was soon embraced, and together they raised three children and now have a grandson. The couple lived in Sydney for 12 years, where Cok studied art and volunteered at the Australian Museum, helping connect Balinese and Australian cultures. This experience reinforced his lifelong commitment to cultural preservation, now central to his work with the Bali Heritage Trust. He notes that much Balinese literature was lost to natural disasters and colonization, prompting villages to reconstruct their histories by combining surviving sources, oral traditions, and archaeological research.

Cok recognizes that rapid development in Bali—driven by tourism, construction, and the loss of farmland—makes it harder to sustain tradition as a living part of society, especially in the south. The challenge, he says, lies in maintaining a cultural system amid strong external influences. Tourist-heavy areas, in particular, require active support and political commitment to protect culture, especially since Bali is promoted globally because of its cultural heritage.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Indonesia Tourism website

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026