NAMES FOR THE PHILIPPINES

Formal Name: Republic of the Philippines (Republika ng Pilipinas). Short Form: Philippines (Pilipinas). Term for Citizens: Filipino. The Republic of the Philippines was first named the Filipinas to honor King Philip II of Spain in 1543. The Philippine Islands was the name used before independence. [Source: CIA World Factbook: Sally E. Baringer, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

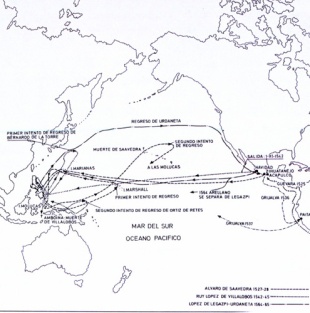

King Philip II of Spain (reigned 1556–1598) ruled Spain during the peak of the Spanish Empire, a period of immense global power, territorial expansion, and staunch Catholicism. Under his rule, Spain, the Netherlands, parts of Italy, and the Americas were united, and he became King of Portugal in 1580. The name Filipinas was coined, when Philip was still a prince (Prince Philip of Asturia), by the Spanish conquistador Ruy Lopez de Villalobos, who sailed from Mexico to the Philippines in 1542 in hopes of setting up a colony in the Philippines but was unable to do so and was unable to make it back to Mexico.

Ferdinand Magellan reached the Philippines in 1521. He claimed the Philippines for Spain and named them the "Islas de San Lazaro" (St. Lazarus' Islands) because he arrived at the archipelago on March 16, 1521, which was the feast day of Saint Lazarus of Bethany. His expedition first sighted the island of Samar before landing on Homonhon Island, marking the first documented European contact with the archipelago. Filipinas replaced Magellan's name, "Islas de San Lazaro," to strengthen Spain's political claim over the archipelago, specifically focusing on honoring the heir to the Spanish throne.

Ruy López de Villalobos (c. 1500–1546) was a Spanish explorer who attempted to establish Spanish control over the Philippines in 1543 under the terms of the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) and the Treaty of Zaragoza (1529). He led an expedition with six ships that left from the west coast of Mexico. The expedition was able to reach the Philippines okay but failed in setting up a colony and making it back to Mexico because the crew of 370 men could not secure enough food through trade, farming, or raiding, and they were unable to obtain reinforcements from New Spain due to limited knowledge of Pacific winds and currents. Forced to abandon the mission, Villalobos retreated to the Portuguese-controlled Moluccas, where he was imprisoned and later died. He reportedly only named the islands of Leyte and Samar “Las Islas Filipinas”. That was eventually applied to the entire Philippine archipelago.

The symbolic name for the Philippines — Juan dela Cruz — is not a Filipino invention. It was coined by R. McCulloch-Dick, a Scottish-born journalist working for the Manila Times in the early 1900s, after discovering it was the most common name in blotters.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FIRST HOMININS IN THE PHILIPPINES: 709,000-YEAR-OLD TOOLS, HOMO LUZONENSIS TABON MAN factsanddetails.com

AUSTRONESIAN PEOPLE OF THE PACIFIC, INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, TAIWAN AND THE PHILIPPINES: ORIGIN, HISTORY, EXPANSION factsanddetails.com

MALAYS AND MALAY-RELATED PEOPLE: HISTORY, DEFINITIONS, ORIGINS, LIFE, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

EARLY HISTORY OF THE PHILIPPINES: MIGRATIONS, DISPLACEMENTS, DNA, factsanddetails.com

PHILIPPINES BEFORE THE ARRIVAL OF THE SPANISH factsanddetails.com

PRE-COLONIAL FILIPINO STATES factsanddetails.com

SPANISH ARRIVE IN THE PHILIPPINES: EXPEDITIONS, LEGAZPI, TAKING CONTROL factsanddetails.com

CHRISTIANIZATION OF THE PHILIPPINES: MISSIONARIES, SUCCESS, FRIAROCRACY factsanddetails.com

PHILIPPINES UNDER SPANISH RULE: LIFE, COLONIZATION, CHINESE factsanddetails.com

MANILA GALLEONS: SPANISH TRADE BETWEEN THE PHILIPPINES AND MEXICO factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF MUSLIMS IN THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

DECLINE OF THE SPANISH IN THE PHILIPPINES AND RISE FILIPINO NATIONALISM factsanddetails.com

JOSE RIZAL’S EXECUTION AND FILIPINO ACTIVISM AND REBELLIONS AGAINST SPAIN factsanddetails.com

SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR (1898) AND ITS IMPACT ON THE PHILIPPINES AND THE NORTHERN PACIFIC factsanddetails.com

U.S. TAKES OVER THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

JAPAN TAKES THE PHILIPPINES: ATTACK, FIGHTING, MACARTHUR, CORREGIDOR factsanddetails.com

DEFEAT OF JAPAN IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

Emergence of a Filipino Idenity

At the beginning of Spanish colonization In the sixteenth century the Philippines was called Las Islas Filipinas. The inhabitants of the Philippines were called "Indios." The term "Filipino" was first applied to Spaniards born in the Philippines (also known as insulares, Creoles and Spanish mestizos) to distinguish them from Spaniards born in Spain (peninsulares). The "luckier" Spaniards born in Spain stressed that they were "Peninsulares." Soon enough, the Spanish and Chinese mestizos were also identified as Filipinos. [Source: “Culture Shock!: Philippines” by Alfredo Roces and Grace Roces, Marshall Cavendish International, 2010; Google AI]

In the late nineteenth century, the meaning of “Filipino” began to change dramatically. Reformists and revolutionaries, most notably José Rizal, redefined the term to include all native inhabitants of the archipelago, regardless of race or regional background. This shift was deliberate and political: it fostered unity among diverse groups and strengthened the growing nationalist movement against Spanish rule.

During the American colonial period (1898–1946), the United States administration officially adopted “Filipino” as the standard term for all inhabitants of the Philippines. The Americans did not continue the Spanish racial classifications such as indio, and the broader usage of “Filipino” became firmly established, solidifying its meaning as a national identity rather than a colonial category.

Brief History of the Philippines

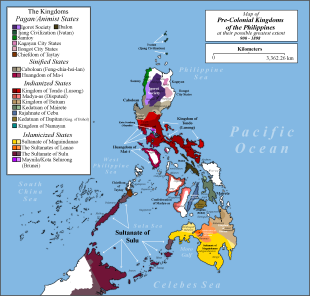

Long before the arrival of Europeans, several waves of Malay peoples arrived in the Philippine archipelago from Southeast Asia. These tribal societies and petty principalities coexisted, maintaining links with China, the East Indies, and other countries in the Indian Ocean. Islam was introduced in the late 14th century. [Source: CIA World Factbook, Jose Florante J. Leyson, M.D., Encyclopedia of Sexuality ~; World Press Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

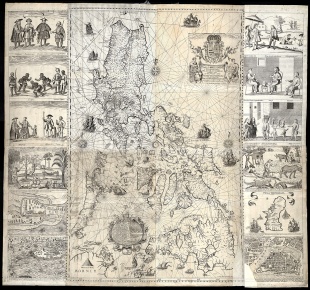

The Philippines became a Spanish colony on March 16, 1521, when Ferdinand Magellan landed near Cebu and claimed the islands for Spain. The first permanent Spanish settlement was founded in 1565, and the islands were later named after Philip II of Spain. The first Spanish settlements were established in 1564, and the colonial capital, Manila, was founded in 1571 and quickly became a key transit point for trade between Mexico and the Far East. Under Spanish rule, most Filipinos converted to Catholicism, except in the southwest islands, where the people remained Muslim. The Spanish occupation was continuous, except for a brief partial occupation by Great Britain from 1762 to 1764. In the shadow of a tepid and erratic Spanish colonial administration, the Catholic Church grew in power and wealth.

Filipinos declared Philippines independence from Spain on June 12, 1898, after more than three centuries of colonial rule. A nationalist movement in the late 1800s led to the 1896 armed uprising and the Spanish-American War. and proclaimed independence. During the Spanish-American War, the United States defeated the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay. Filipino forces took control of much of Luzon, and Manila was eventually captured with American assistance. Under the Treaty of Paris, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States.

In 1898, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States for $20 million. When Filipino nationalists proclaimed independence, the United States refused to recognize it, leading to a six-year war (1899–1905) in which American forces suppressed the resistance. In 1916, Filipinos were allowed to elect a Senate and House of Representatives, though the Governor General remained American, and in 1935 a U.S.-modeled Commonwealth government was established.

In 1935, the Philippines became a self-governing commonwealth under President Manuel Quezon, who prepared the country for independence after a 10-year transition. However, World War II disrupted this plan when Japan attacked and occupied the Philippines in 1941–1942. American and Filipino forces fought together to liberate the country in 1944–1945. On July 4, 1946, the Philippines officially gained independence from the United States, becoming the first Asian U.S. colony to do so.

In the 1970s, Muslim (Moro) secessionists sought autonomy in Mindanao, while political unrest grew nationwide. In 1972, President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law, citing threats from radical youth groups and leftist insurgents. Although some reforms were introduced, poverty, unemployment, and opposition persisted. The 1983 assassination of opposition leader Benigno Aquino Jr. intensified protests. After the disputed 1986 elections, Corazon Aquino led a nonviolent resistance movement that challenged Marcos’s rule. Marcos’s 20-year presidency ended in 1986 when the “People Power” movement (EDSA I) forced him into exile and installed Corazon Aquino as president. Her administration faced economic difficulties, poverty, communist insurgency, and several coup attempts between 1987 and 1990. Although instability persisted, government forces—assisted by U.S. troops stationed in the country—successfully suppressed a major coup attempt in 1989.

In 1994, the Philippine government signed a cease-fire with Muslim separatist guerrillas, though some factions rejected the agreement. Fidel Ramos, elected in 1992, brought greater political stability and advanced economic reforms, and in the same year the United States closed its last military bases in the country. Joseph Estrada won the presidency in 1998 but was removed in 2001 after a failed impeachment trial over corruption, prompting another “People Power” uprising (EDSA 2). He was succeeded by Vice President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.

Macapagal-Arroyo was elected to a full term in 2004, though her presidency faced corruption allegations. Despite this, the Philippine economy avoided contraction during the 2008 global financial crisis and grew throughout her administration. Benigno Aquino III was elected in 2010. The government continues to confront security challenges, including Moro insurgencies in the south—leading to a peace accord with the Moro National Liberation Front and peace talks with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front—as well as the Maoist-inspired New People's Army. The Philippines also faces rising tensions with China over disputed claims in the South China Sea.

Historical Themes in the Philippines

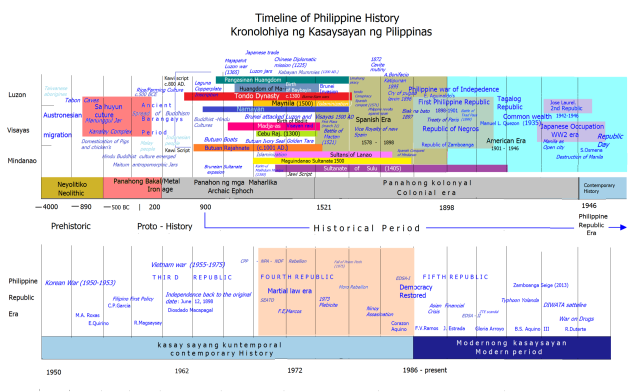

Philippine history is commonly divided into four major periods: 1) the pre-Spanish Malay era (before 1521), when trade with China was common; 2) the Spanish era (1521–1898); 3) the American era (1898–1946); and the 4) post-independence period (1946 to the present). Each phase brought significant political, social, and cultural changes that shaped the nation’s identity. It is often said that Filipinos are Malay in heritage, Spanish in romance, Chinese in commerce, and American in ambition. Throughout history, foreign contacts and colonial rule deeply affected the country’s cultural development, sometimes positively and sometimes negatively. These historical experiences left lasting marks on Filipino values, attitudes, and behavior. Understanding the evolution of Philippine culture helps explain why Filipinos think and act as they do today. [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale, 2008; “Culture Shock!: Philippines” by Alfredo Roces and Grace Roces, Marshall Cavendish International, 2010]

The Philippines is the third largest English speaking country in the world due to American influence. In ancient times, it had the closest links culturally to Southeast Asia and China. With the exception of Mindanao, and the islands south of it, influence from the islands that now make up Indonesia is thought to have been minimal. Prior to Spanish colonization in 1521, the Filipinos had a rich culture and were trading with the Chinese and the Japanese.

Alfredo Roces and Grace Roces wrote in “Culture Shock!: Philippines”:History has deeply shaped the Filipino national character. Despite colonial oppression and the suppression of idealistic leaders during Spanish and American rule, Filipinos have shown resilience and enduring positive traits that suggest long-term strength and survival. At the same time, this colonial past helps explain present-day confusion over values and identity. Today, Filipinos often debate which values, manners, and virtues should define them, while scholars and artists continue searching for a clear Filipino identity rooted in the country’s diverse heritage. [Source: “Culture Shock!: Philippines” by Alfredo Roces and Grace Roces, Marshall Cavendish International, 2010]

Since 1986, when the “People Power” movement peacefully removed a dictator, Filipinos have increasingly shaped their own destiny. This form of protest—now protected by the Constitution—reflects elements of Filipino culture, including a communal and celebratory spirit. A uniquely Filipino democracy is gradually developing, even amid challenges like political patronage and corruption. For outsiders, some troubling aspects of modern Philippine society should be viewed as part of a transitional phase, as the nation continues to reconcile its complex cultural influences and recover from a history marked by colonization and armed conflict.

Impact of Colonialism on the Philippines

The modern Philippines has been shaped very much by its colonial experience, which some Filipinos describe as “300 years in a convent under Spain followed by 50 years in Hollywood.” The archipelago endured 381 years of Spanish and American rule. However, some places like Mindanao and even the interior of Luzon were never controlled.

Spain's colonization brought about the construction of Intramuros in 1571, a "Walled City" comprised of European buildings and churches, replicated in different parts of the archipelago. In 1898, after 350 years and 300 rebellions, the Filipinos, with leaders like Jose Rizal and Emilio Aguinaldo, succeeded in winning their independence. [Source: Philippines Department of Tourism]

A well-used adage here is that the Philippines spent 400 years in a convent then 50 years in Hollywood, referring to Spanish then American colonial rule. In 1898, the Philippines became the first and only colony of the United States. Following the Philippine-American War, the United States brought widespread education to the islands. Filipinos fought alongside Americans during World War II, particularly at the famous battle of Bataan and Corregidor which delayed Japanese advance and saved Australia. They then waged a guerilla war against the Japanese from 1941 to 1945. The Philippines regained its independence in 1946.

Whereas the economic legacy of colonialism, including the relative impoverishment of a very large segment of the population, left seeds of dissension in its wake, not all of the enduring features of colonial rule were destabilizing forces. Improvements in education and health had done much to enhance the quality of life. More important in the context of stabilizing influences was the profound impact of Roman Catholicism. The great majority of the Filipino people became Catholic, and the prelates of the church profoundly influenced the society. [Source: Library of Congress]

Influence of History, Spain and America on Filipino Culture

According to the Philippines Department of Tourism: Filipinos value freedom deeply, having carried out two largely peaceful, bloodless revolutions against regimes widely seen as corrupt. The country today functions as a lively democracy, with numerous national newspapers, television networks, cable channels, and radio stations reflecting active public discourse. More than three centuries of Spanish rule and five decades of American influence have made the Philippines culturally distinct within Asia. Beneath these strong foreign layers, however, the Filipino spirit continues to seek and express its own unique identity. [Source: Philippines Department of Tourism]

This identity is vividly expressed through music and dance. Filipinos love social gatherings, celebration, and performance, best seen in the fiesta, the province-wide festival that blends street dancing, talent shows, religious devotion, and communal feasting. Often celebrating harvests or patron saints, fiestas feature drum rhythms with Latin influences, colorful floats, and creative costumes. From pilgrim processions to lively street parties, these celebrations are inclusive and community-centered.

Artistic expression is also woven into daily life. Filipinos show a natural flair for color, design, and craftsmanship, visible not only in galleries but in handicrafts, fashion, churches, parks, jeepneys, embroidery, tribal tattoos, and traditional weaving such as that of Lang Dulay. Creativity becomes a way of asserting cultural identity.

Filipino cuisine likewise reflects layered cultural influences and a deep connection to family and home. Dishes vary from region to region, yet many are widely shared, such as adobo, often considered the national dish, prepared in countless local variations. With its diverse islands and traditions, Philippine culture resembles a festive buffet of flavors and experiences.

A common saying notes that the Philippines endured 300 years of Spanish rule and 50 years of Hollywood, highlighting the depth of Western influence. Some observers have linked independence with lingering self-doubt about national identity. Even Imelda Marcos once reflected that she learned American symbols before Filipino ones—an anecdote that illustrates the powerful cultural imprint left by colonial history.

One Legacy of Colonialism on the Philippines: A Few Rich and Lots of Poor

Many of the most intractable problems in the Philippines can be traced to the country's colonial past. One major source of tension and instability stems from the great disparity in wealth and power between the affluent upper social stratum and the mass of low-income, often impoverished, Filipinos. In 1988 the wealthiest 10 percent of the population received nearly 36 percent of the income, whereas the poorest 30 percent of the population received less than 15 percent of the income. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The roots of the disparity between the affluent and the impoverished lie in the structure established under Spanish rule, lasting from the first settlement under Miguel López de Legazpi in 1565 to the beginning of United States rule in 1898. Friars of various Roman Catholic orders, acting as surrogates of the Spanish government, had integrated the scattered peoples of the barangays into administrative entities and firmly implanted Roman Catholicism among them as the dominant faith — except in the southern Muslim-dominated portion of the archipelago. Over the centuries, these orders acquired huge landed estates and became wealthy, sometimes corrupt, and very powerful. *

Eventually, their estates were acquired by principales (literally, principal ones; a term for the indigenous local elite) and Chinese mestizos eager to take advantage of expanding opportunities in agriculture and commerce. The children of these new entrepreneurs and landlords were provided education opportunities not available to the general populace and formed the nucleus of an emerging, largely provincially based, sociocultural elite — the ilustrados — who dominated almost all aspects of national life in later generations. *

Peasant Revolts in the Philippines

The peasants revolted from time to time against their growing impoverishment on the landed estates. They were aided by some reform-minded ilustrados, who made persistent demands for better treatment of the colony and its eventual assimilation with Spain. In the late nineteenth century, inflamed by various developments, including the martyrdom of three Filipino priests, a number of young ilustrados took up the nationalist banner in their writings, published chiefly in Europe. During the struggle for independence against Spain (1896-98), ilustrados and peasants made common cause against the colonial power, but not before a period of ilustrado vacillation, reflective of doubts about the outcome of a confrontation that had begun as a mass movement among workers and peasants around Manila. Once committed to the struggle, however, the ilustrados took over, becoming the articulators and leaders of the fight for independence — first against Spain, then against the United States. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Philippine peasant guerrilla forces contributed to the defeat of the Spanish. When the Filipinos were denied independence by the United States, they focused their revolutionary activity on United States forces, holding out in the hills for several years. The ilustrado leadership chose to accommodate to the seemingly futile situation. Once again, ilustrados found themselves in an intermediary position as arbiters between the colonial power and the rest of the population. Ilustrados responded eagerly to United States tutelage in democratic values and process in preparation for eventual Philippine self-rule, and, in return for their allegiance, United States authorities began to yield control to the ilustrados. Although a massive United States-sponsored popular education program exposed millions of Filipinos to the basic workings of democratic government, political leadership at the regional and national levels became almost entirely the province of families of the sociocultural elite. Even into the 1990s, most Philippine political leaders belonged to this group. *

Members of the peasantry, for their part, continued to stage periodic uprisings in protest against their difficult situation. As the twentieth century progressed, their standard of living worsened as a result of population growth, usury, the spread of absentee landlordism, and the weakening of the traditional patron-client bonds of reciprocal obligation. *

Famous Filipinos in Politics

Filipinos have made many of their most significant contributions in politics and national leadership. Among the most prominent figures is Jose Rizal (1861–1896), a novelist, poet, physician, and national hero whose writings inspired the movement against Spanish rule. Andres Bonifacio (1863–1897) led the secret Katipunan society in revolution against Spain, while Emilio Aguinaldo (1869–1964) commanded revolutionary forces and became president of the First Philippine Republic in 1899. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

In the 20th century, important leaders included Manuel L. Quezon (1878–1944), the first president of the Commonwealth; Ramon Magsaysay (1907–1957), noted for combating the Hukbalahap insurgency; and Carlos P. Romulo (1899–1985), a Pulitzer Prize–winning author and diplomat who served as president of the UN General Assembly.

Ferdinand Marcos (1917–1989), a former guerrilla fighter during the Japanese occupation, dominated Philippine politics from his election in 1965 until his ouster in 1986. His wife, Imelda Marcos (b. 1929), became an influential figure in government during the 1970s. Leading critics of the regime included Benigno Aquino Jr. (1933–1983) and Jaime Sin (1928–2005), Archbishop of Manila and later a cardinal. After Marcos went into exile in 1986, Corazon Aquino, widow of Benigno Aquino Jr., assumed the presidency. She was succeeded by Fidel Ramos (1992–1998), followed by Joseph Estrada (1998–2001), and then Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, who took office in 2001.

National Heroes in the Philippines

Chief Lapu-Lapu is credited with killing Ferdinand Magellan in 1521, when the Spanish expedition sought to claim the Philippine islands for Spain under King Philip II. He is often honored as the first Filipino to resist colonial rule and is regarded as a national hero. Some note the irony that lapu-lapu is also the Filipino word for a grouper fish. [Source: Canadian Center for Intercultural Learning]

At the end of the nineteenth century, three major figures of the anti-Spanish resistance became widely recognized national heroes: Jose Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, and Emilio Aguinaldo. Rizal, an internationally known scholar, writer, and poet, is often considered the foremost national hero. Though he advocated peaceful reform, he was arrested and executed in 1896 for alleged involvement in revolutionary activities, an act that intensified the independence movement. The revolution ultimately faltered after the Spanish-American War, when the United States replaced Spain as the colonial power. American authorities later emphasized Rizal’s pacifism, further elevating his reputation.

Some pro-American Filipinos also regard U.S. General Douglas MacArthur as a hero for his leadership in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, which helped liberate the Philippines from Japanese occupation during World War II. However, his later actions against Filipino freedom fighters affected perceptions of his legacy.

After independence in 1945, political power largely remained with elite families. Still, leaders such as Ramon Magsaysay, Ferdinand Marcos, Fidel Ramos, and Joseph Estrada were seen as popular figures during their time in office. Of these, Magsaysay—who died in a 1957 plane crash in Cebu while still president—is often remembered as having preserved an untarnished reputation.

Benigno Aquino Jr., widely known as Ninoy, is also regarded by many as a national hero despite his contentious political career. Returning from exile in 1983 to challenge the Marcos regime, he was assassinated upon arrival at Manila International Airport (later renamed in his honor). His widow, Corazon Aquino, reluctantly led the opposition in the disputed 1986 election, which triggered the “People Power” revolution. After Marcos fled to Hawaii, she became president and remains widely admired as a symbol of democratic restoration.

Timeline of Philippines History After the Arrival of Europeans

Spanish Period:

1521: Ferdinand Magellan arrives in the Philippines while searching for the Moluccas and is killed in battle by native chieftain Lapu-Lapu.

1543: Spanish explorer Ruy Lopez de Villalobos names the islands Filipinas in honor of Spain’s King Philip II.

1565: Miguel Lopez de Legazpi establishes a Spanish base in Cebu and later transfers the colonial capital to Manila.

1575: Spain consolidates control over non-Islamic regions and monopolizes trade.

1896: Nationalist Jose Rizal is executed by Spanish authorities and later honored as a national hero. [Source: World Encyclopedia, Oxford University Press 2005]

American Period:

1898: Following the Spanish-American War, Spain cedes the Philippines to the United States for $20 million under the Treaty of Paris.

1900: The United States establishes a civil government and promises eventual independence.

1935: Manuel L. Quezon is elected president of the Commonwealth under a new constitution.

1941: Japanese forces invade Luzon during World War II.

1942: Japan captures Manila after U.S. and Filipino troops on Bataan surrender to Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita.

1945: Japanese occupation ends; the Philippines becomes a founding member of the United Nations.

Post-Independence Period

1946: The Philippines gains independence from the United States on July 4, with Manuel Roxas as president.

1947: The Philippines and the United States sign a Military Bases Agreement.

1948: President Roxas dies and is succeeded by Elpidio Quirino.

1950s: The Communist Hukbalahap movement collapses, and the economy recovers, making the Philippines one of Asia’s most prosperous nations after Japan.

1953: Ramon Magsaysay is elected president.

1957: President Magsaysay dies in a plane crash and is succeeded by Carlos P. Garcia.

1961: Diosdado Macapagal defeats Garcia in the presidential election.

Marcos Era:

1965: Ferdinand Marcos is elected president.

1967: The Philippines becomes a founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

1969: Marcos is re-elected; the New People's Army is founded.

1972: Marcos declares martial law, suspends the constitution, dissolves the legislature, and intensifies actions against opposition and communist rebels; Muslim insurgency in the south escalates.

1981: Marcos lifts martial law and wins another six-year term.

1983: Senator Benigno Aquino Jr. is assassinated upon returning from U.S. exile, heightening unrest.

After Marcos:

1986: A peaceful “People Power” revolution forces Marcos into exile; Corazon Aquino becomes president and a new constitution is ratified.

1989: Limited autonomy is granted to Muslim provinces; tensions rise with China over the Spratly Islands; a coup attempt occurs.

1990: A 7.7-magnitude earthquake kills over 1,600 people; typhoons devastate the Visayas.

1991: Mount Pinatubo erupts, burying towns and affecting Clark Air Base and Subic Naval Base.

1992: Fidel V. Ramos is elected president and launches “Philippines 2000”; the Senate rejects renewal of U.S. base agreements.

1990s: Economic growth resumes, and the Philippines is labeled one of Asia’s emerging “tiger cub” economies.

1998: Joseph Estrada wins the presidency; the fiscal deficit rises sharply.

2000: Estrada becomes the first Philippine president impeached by Congress; after mass protests, Vice President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo assumes the presidency.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Library of Congress, Philippines Department of Tourism, Encyclopedia.com, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Wikipedia, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, Lonely Planet Guides, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, The Conversation, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Google AI, and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026