AMERICAN COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE PHILIPPINES

In 1902, the Philippines became an American territory. William Howard Taft, who would later become president, served as the first territorial governor. Over the next two decades, American attitudes toward the Philippines changed, and the islands were granted Commonwealth status in 1933. The United States promised independence after twelve years, while retaining rights to military bases. [Source: Sally E. Baringer, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

The Philippines was a colony of the United States for about 50 years and was the only sizable colony the United States every had. The United States took possession of the Philippines—and Guam and Puerto Rico—after it won the Spanish-American War, which overnight made the United States into a world power. The Americans gave the Philippines public education, the English language, and agricultural and industrial development.

U.S. rule over the Philippines had two phases. The first phase was from 1898 to 1935, during which time Washington defined its colonial mission as one of tutelage and preparing the Philippines for eventual independence. Political organizations developed quickly, and the popularly elected Philippine Assembly (lower house) and the U.S.-appointed Philippine Commission (upper house) served as a bicameral legislature. The “ilustrados”formed the Federalista Party, but their statehood platform had limited appeal. In 1905 the party was renamed the National Progressive Party and took up a platform of independence. The Nacionalista Party was formed in 1907 and dominated Filipino politics until after World War II. Its leaders were not ilustrados. Despite their “immediate independence” platform, the party leaders participated in a collaborative leadership with the United States. A major development emerging in the post-World War I period was resistance to elite control of the land by tenant farmers, who were supported by the Socialist Party and the Communist Party of the Philippines. Tenant strikes and occasional violence occurred as the Great Depression wore on and cash-crop prices collapsed. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The second period of United States rule—from 1936 to 1946—was characterized by the establishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines and occupation by Japan during World War II. Legislation passed by the U.S. Congress in 1934 provided for a 10-year period of transition to independence. The country’s first constitution was framed in 1934 and overwhelmingly approved by plebiscite in 1935, and Manuel Quezon was elected president of the commonwealth. Quezon later died in exile in 1944 and was succeeded by Vice President Sergio Osme a. Japan attacked the Philippines on December 8, 1941, and occupied Manila on January 2, 1942. Tokyo set up an ostensibly independent republic, which was opposed by underground and guerrilla activity that eventually reached large-scale proportions. A major element of the resistance in the Central Luzon area was furnished by the Huks (short for Hukbalahap, or People’s Anti-Japanese Army). Allied forces invaded the Philippines in October 1944, and the Japanese surrendered on September 2, 1945. *

RELATED ARTICLES:

SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR (1898) AND ITS IMPACT ON THE PHILIPPINES AND THE NORTHERN PACIFIC factsanddetails.com

DECLINE OF THE SPANISH IN THE PHILIPPINES AND RISE FILIPINO NATIONALISM factsanddetails.com

JOSE RIZAL’S EXECUTION AND FILIPINO ACTIVISM AND REBELLIONS AGAINST SPAIN factsanddetails.com

THE PHILIPPINES: THE UNITED STATES’ FIRST COLONY factsanddetails.com

PHILIPPINES ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE UNDER THE UNITED STATES factsanddetails.com

INDEPENDENCE FOR THE PHILIPPINES AFTER WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

JAPAN TAKES THE PHILIPPINES: ATTACK, FIGHTING, MACARTHUR, CORREGIDOR factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF THE PHILIPPINES: BATAAN DEATH MARCH, PUPPET STATE, RESISTANCE factsanddetails.com

BATTLE OF LEYTE: LAND AND SEA FIGHTING, MACARTHUR, BATTLESHIPS factsanddetails.com

BATTLE OF MANILA IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

DEFEAT OF JAPAN IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

Why Did U.S. Want the Philippines

By the late nineteenth century, American interest in the Philippines stemmed largely from a desire to expand the nation’s economic reach into the Pacific and Asia. As the western frontier in the United States appeared to be closing in the 1890s, policymakers and business leaders increasingly looked overseas for new markets and investment opportunities. Asia—especially China—was viewed as a vast and largely untapped commercial frontier that could help prevent future economic downturns like those the country had experienced in the previous decades. [Source: Dictionary of American History, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

However, American ambitions in East Asia faced stiff competition from other imperial powers, including United Kingdom, France, Russia, Germany, and Japan. Each sought to secure trade privileges, territory, or spheres of influence in China and the broader Asian region. In this competitive imperial environment, the Philippines held strategic value. The islands could serve as both a naval station and a commercial hub, enabling the United States to project power and safeguard its economic interests in Asia. As tensions between the United States and Spain escalated during the Cuban crisis, the administration of William McKinley recognized an opportunity. By confronting Spain in both the Caribbean and the Pacific, the United States could resolve immediate diplomatic conflicts while simultaneously advancing its broader strategic and economic objectives in Asia.

Taking control of the Philippines raised far more controversy than expansion in the Caribbean. Although President William McKinley publicly expressed reluctance, he ultimately supported annexation, believing it would secure American interests in Asia, prevent rival powers from seizing the islands, and address what he saw as Filipino unpreparedness for self-rule. Imperialists such as Theodore Roosevelt defended the move as both strategic and a moral duty to promote self-government, while others emphasized its commercial value as a gateway to Asian trade. Republicans also recognized its political advantages following victory in war.

Opposition was intense. Prominent anti-imperialists, including Andrew Carnegie and Mark Twain, condemned annexation as a betrayal of American ideals of liberty. Critics also raised racial concerns, feared economic competition from cheap labor and goods, and warned about the costs of defending distant territories. Despite the controversy, the Senate ratified the Treaty of Paris in February 1899, and McKinley’s reelection in 1900 suggested broad public support for imperial expansion.

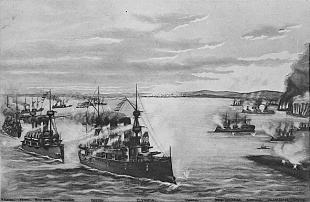

Spanish-American War

The Spanish-American War should be called Spanish-American-Cuban-Philippine War because Cuba is where much of the action took place and the Philippines was affected the most by its outcome. Spain was pushed into the war after the sinking of the U.S. ship the Maine in Cuba, which killed 260 officers and men, but the Spanish actually had nothing to do with. Among those who reported on the war were Mark Twain, who “expertly excoriated”it .

The Spanish-American War was conducted under U.S. President William McKinley, who was known mainly as a ditherer. At first, like most Americans, he didn't even known where the Philippines was. The conflict spilled form Cuba into the Philippines because the United States realized the weakness of Spain and figured why stop at Cuba, why not seize all of Spain's possessions, which included the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Guam.

Under the Treaty of Paris of December 10, 1898, which formally ended the Spanish-American War the Philippines—in addition to Cuba, Puerto Rico and Guam—were ceded to the United States, which "bought" the title for the Philippines from Spain for $20 million. After the Spanish surrendered there was debate in America about what to do with the Philippines: give them back to Spain, grant the islands independence, or claim them as a colony. Dewey had reported that the Filipino were ready for independence but later retracted the statement. Pushed by Roosevelt, and business interests, McKinley decided to keep the Philippines and announced it had been "benevolently assimilated." The Filipino upper class was happy with the peace treaty but the rebels who fought against Spain and declared Filipino independence were not. Dewey stayed on in the Philippines for a year and lived like a sultan. When he returned to the United States in 1899 he was welcomed with a ticker tape parade and was given a special ceremonial sword by Congress.

See Separate Article: SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR (1898) AND ITS IMPACT ON THE PHILIPPINES AND THE NORTHERN PACIFIC factsanddetails.com

Filipino Rebels Declare Philippines Independence

After returning to the islands, Aguinaldo wasted little time in setting up an independent government. On June 12, 1898, a declaration of independence, modeled on the American one, was proclaimed at his headquarters in Cavite. It was at this time that Apolinario Mabini, a lawyer and political thinker, came to prominence as Aguinaldo's principal adviser. Born into a poor indio family but educated at the University of Santo Tomás, he advocated "simultaneous external and internal revolution," a philosophy that unsettled the more conservative landowners and ilustrados who initially supported Aguinaldo. [Source: Library of Congress *]

For Mabini, true independence for the Philippines would mean not simply liberation from Spain (or from any other colonial power) but also educating the people for self-government and abandoning the paternalistic, colonial mentality that the Spanish had cultivated over the centuries. Mabini's The True Decalogue, published in July 1898 in the form of ten commandments, used this medium, somewhat paradoxically, to promote critical thinking and a reform of customs and attitudes. His Constitutional Program for the Philippine Republic, published at the same time, elaborated his ideas on political institutions. *

On September 15, 1898, a revolutionary congress was convened at Malolos, a market town located thirty-two kilometers north of Manila, for the purpose of drawing up a constitution for the new republic. A document was approved by the congress on November 29, 1898. Modeled on the constitutions of France, Belgium, and Latin American countries, it was promulgated at Malolos on January 21, 1899, and two days later Aguinaldo was inaugurated as president. *

American observers traveling in Luzon commented that the areas controlled by the republic seemed peaceful and well governed. The Malolos congress had set up schools, a military academy, and the Literary University of the Philippines. Government finances were organized, and new currency was issued. The army and navy were established on a regular basis, having regional commands. The accomplishments of the Filipino government, however, counted for little in the eyes of the great powers as the transfer of the islands from Spanish to United States rule was arranged in the closing months of 1898. *

Treaty of Paris Gives the Philippines to the U.S. and Angers Filipinos

In late September 1898, treaty negotiations were initiated between Spanish and American representatives in Paris. The Treaty of Paris was signed on December 10, 1898. Among its conditions was the cession of the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico to the United States (Cuba was granted its independence); in return, the United States would pay Spain the sum of US$20 million. The nature of this payment is rather difficult to define; it was paid neither to purchase Spanish territories nor as a war indemnity. In the words of historian Leon Wolff, "it was . . . a gift. Spain accepted it. Quite irrelevantly she handed us the Philippines. No question of honor or conquest was involved. The Filipino people had nothing to say about it, although their rebellion was thrown in (so to speak) free of charge." [Source: Library of Congress *]

The Treaty of Paris aroused anger among Filipinos. Reacting to the US$20 million sum paid to Spain, La Independencia (Independence), a newspaper published in Manila by a revolutionary, General Antonio Luna, stated that "people are not to be bought and sold like horses and houses. If the aim has been to abolish the traffic in Negroes because it meant the sale of persons, why is there still maintained the sale of countries with inhabitants?" Tension and ill feelings were growing between the American troops in Manila and the insurgents surrounding the capital.

According to Lonely Planet: “Filipino revolutionaries were openly defying the Americans, and the Americans were antagonising the Filipinos. Any dreams of impending Filipino independence were shattered in 1899 when Malolos, the makeshift capital of President Aguinaldo's Philippine Republic, was captured by American troops - led by General Arthur MacArthur (Douglas's father). [Source: Lonely Planet]

In addition to Manila, Iloilo, the main port on the island of Panay, also was a pressure point. The Revolutionary Government of the Visayas was proclaimed there on November 17, 1898, and an American force stood poised to capture the city. Upon the announcement of the treaty, the radicals, Mabini and Luna, prepared for war, and provisional articles were added to the constitution giving President Aguinaldo dictatorial powers in times of emergency. President William McKinley issued a proclamation on December 21, 1898, declaring United States policy to be one of "benevolent assimilation" in which "the mild sway of justice and right" would be substituted for "arbitrary rule." When this was published in the islands on January 4, 1899, references to "American sovereignty" having been prudently deleted, Aguinaldo issued his own proclamation that condemned "violent and aggressive seizure" by the United States and threatened war. *

Philippine-American War (1899-1902)

After the Spanish-American War, Filipinos rebels rose up in revolt against the Americans. Some American historians called the ensuing war the Philippine Insurrection. Many Filipinos saw it as a legitimate struggle for independence. Sometimes referred to as America's "First Vietnam," the Philippine-American War (1899-1902) occurred when Filipino rebels that had fought side by by side with the Americans during the Spanish-American War took up arms against the American military government set up after the Spanish-American War. Some 16,000 Filipino soldiers who fought with the Americans died. The size of nationwide guerrilla movement against the Americans was not known. By some estimates 250,000 Filipinos, the majority of them civilians were killed in the conflict.

The conflict against the Filipino rebels was much more difficult than the Spanish-American War. Generally ignored today, the Philippine War (1899–1901) was one of the bloodiest in American history. Some 200,000 American soldiers took part, and with 4,300 deaths, the United States suffered nearly ten times the fatalities of

After the Spanish American War, the U.S. reneged on a promise of independence for the Filipinos and refused to let Filipino rebels enter Intramuros (Manila’s Walled City). The Filipino rebels had supported the United States during the Spanish-American War because they thought the Americans had come to the Philippines to liberate it from Spain as they had done in Cuba. They felt betrayed when the United States decided to make the Philippines into a U.S. colony. In 1899, Gen. Aguinaldo became president of the revolutionary First Philippine Republic and continued guerrilla resistance in the mountains of northern Luzon. The first Republic of the Philippines was established during this time at the Barasoin Church in Malolos, Bulacan, 48 kilometers northwest of Manila, in the midst of what is considered the land of the deepest (malalim ) and purest dialect of Tagalog.

Many of the American soldiers who fought in the Philippines beginning in 1898 had cut their teeth in the Indian Wars in the United States. They claimed they were bringing freedom and democracy to the Filipinos the same they did to the Indians and adopted the famous Indian fighter slogan for their own purposes: "The only good Filipino is a dead one." There was a large amount of opposition to the war in the United States. Many say it as hypocritical for traditional “anti-imperialists” to be fighting an imperialist war. Mark Twain wrote, “I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.”

The war lasted for more than two years. The rebels fought under Emilio Aguinaldo. He had earlier been brought out of exile to the Philippines on an American ship from Hong Kong. The United States had sold him thousands of rifles to use in his fight against the Spanish.

Fighting During Philippine-American War

In account the conflict began on February 4, 1899, 36 hours before the Spanish-American War treaty was ratified by the U.S. Congress, when an American sentry shot some drunk Filipino soldiers that had mistakenly walked across American lines and fired back at back at the sentry. According to another account two American privates on patrol in a suburb of Manila killed Three Filipino soldiers. "The first blow was struck by the inhabitants," U.S. President William McKinley said, "There will be no useless parley, no pause, until...the insurrection is suppressed and American authority acknowledged and established." [Source: David Haward Bain, Smithsonian, May 1989]

The Filipino troops, armed with old rifles and bolos and carrying anting-anting (magical charms), were no match for American troops and their superior firepower in open combat, but they were formidable opponents in guerrilla warfare. The Filipino forces were quickly driven from Manila into the jungles of Luzon. There they took off their uniforms and blended into the population and used guerilla tactic against the Americans. Aguinaldo and a small band of loyalist ran their campaign from a remote rain forest camp in Sierra Madre mountains in northeast Luzon.

For General Ewell S. Otis, commander of the United States forces, who had been appointed military governor of the Philippines, the conflict began auspiciously with the expulsion of the rebels from Manila and its suburbs by late February and the capture of Malolos, the revolutionary capital, on March 31, 1899. Aguinaldo and his government escaped, however, establishing a new capital at San Isidro in Nueva Ecija Province. The Filipino cause suffered a number of reverses. The attempts of Mabini and his successor as president of Aguinaldo's cabinet, Pedro Paterno, to negotiate an armistice in May 1899 ended in failure because Otis insisted on unconditional surrender. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Still more serious was the murder of Luna, Aguinaldo's most capable military commander, in June. Hot-tempered and cruel, Luna collected a large number of enemies among his associates, and, according to rumor, his death was ordered by Aguinaldo. With his best commander dead and his troops suffering continued defeats as American forces pushed into northern Luzon, Aguinaldo dissolved the regular army in November 1899 and ordered the establishment of decentralized guerrilla commands in each of several military zones. More than ever, American soldiers knew the miseries of fighting an enemy that was able to move at will within the civilian population in the villages. The general population, caught between Americans and rebels, suffered horribly. *

According to historian Gregorio Zaide, as many as 200,000 civilians died, largely because of famine and disease, by the end of the war. Atrocities were committed on both sides. The term concentration camp was first used to describe a form of incarceration used by the Spanish military during the Cuban insurrection, Americans in the Philippines and the British during the Boer war. These were harsh places where many people died but were not in the league of the German concentration camps.

Fighting Breaks Out Throughout the the Philippines During Philippine-American War

Although Aguinaldo's government did not have effective authority over the whole archipelago and resistance was strongest and best organized in the Tagalog area of Central Luzon, the notion entertained by many Americans that independence was supported only by the "Tagalog tribe" was refuted by the fact that there was sustained fighting in the Visayan Islands and in Mindanao. Although the ports of Iloilo on Panay and Cebu on Cebu were captured in February 1899, and Tagbilaran, capital of Bohol, in March, guerrilla resistance continued in the mountainous interiors of these islands. Only on the sugar-growing island of Negros did the local authorities peacefully accept United States rule. On Mindanao the United States Army faced the determined opposition of Christian Filipinos loyal to the republic. *

The Moros on Mindanao and on the Sulu Archipelago, suspicious of both Christian Filipino insurrectionists and Americans, remained for the most part neutral. In August 1899, an agreement had been signed between General John C. Bates, representing the United States government, and the sultan of Sulu, Jamal-ul Kiram II, pledging a policy of noninterference on the part of the United States. In 1903, however, a Moro province was established by the American authorities, and a more forward policy was implemented: slavery was outlawed, schools that taught a non-Muslim curriculum were established, and local governments that challenged the authority of traditional community leaders were organized. A new legal system replaced the sharia, or Islamic law. United States rule, even more than that of the Spanish, was seen as a challenge to Islam. Armed resistance grew, and the Moro province remained under United States military rule until 1914, by which time the major Muslim groups had been subjugated. *

Ambush and Retaliation in Balangiga

The Filipinos' guerrilla tactics prompted American soldiers to become increasingly brutal. The soldiers viewed the enemy as subhuman and justified their savage tactics to suppress the insurrection. The Filipino rebels were defeated in several major battles and many Filipinos were placed in "relocation" camps (concentration camps). There were also some nasty ambushes and retaliations. In the town of Balangiga on the island of Samar, 380 miles southeast of Manila, U.S. troops were called into weed out rebels making trouble there. The soldiers angered the local people when they turned the town hall and a convent into barracks for the soldiers. [Source: David Haward Bain, Smithsonian, May 1989]

At the signal of bells ringing in a local church, rebels dressed as women in mourning grabbed bolos (large-machete-like knives) from coffins, said to contain the bodies of children killed by cholera, and attacked the American troops. Only 22 of 74 Americans survived. Many of the dead were hacked to pieces. It was the worst American defeat during the Philippines rebellion.

In retaliation,, Gen. Jacob “Hell-Roaring Jake” Smith sent in more troops and gave them orders to kill anyone over the age of 10 years old, deemed “capable of bearing arms...against the U.S.” He said, “I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn: the more you kill and burn, the better it will please me.” [After an investigation Smith was later court martialed and cashiered]

As many as 5,000 Filipino may have been killed. Balangiga was pacified. The Americans burned the village church and seized the bell and took them to them to Cheyenne Wyoming, where they still sit today at F.E. Warren Air Force Base. Filipinos want the bells back. Wyoming veterans have refused and only an act of Congress can force them to turn them over.

Capture of Aguinaldo'

The American figured that the only way to end the conflict was to capture Aguinaldo. The assignment to achieve this was given to Col. Frederick Funston, a veteran of "filibuster" campaigns in Cuba. His idea was to move on the camp posing as prisoners with a group of Macabebes (a group of Filipinos fighting on the American side) posing as rebels.

Funston's unit was dropped off by a ship on the coast near Aguinaldo’s camp. They marched more than 100 miles through unforgiving jungle and over cliffs, ravines and one steep 5,000-foot ridge after another. Their food supplies ran low and they were forced to eat limpets from rocks and tiny fish they caught in streams to survive.

The prisoner ploy worked. The Macabebes entered Aguinaldo's camp as the rebels were making preparations for a fiesta to celebrate his 32nd birthday. The rebels believed the story about the American prisoners, but were quickly sent scurrying into the forest when the Macabebes opened fire on them. When he heard the noise Aguinaldo emerged from a nipa-palm and shouted, "Stop that foolishness. Don't waste ammunition." There was brief gun battle and he was captured. By the time the Americans arrived the fighting was over. When Col. Funto introduced himself to Aguinaldo as he was taken prisoner, the rebel commander was only beginning to understand what had happened. Tears appeared in his eyes and he said "Is this not some joke?"

End of the Philippine-American War

Aguinaldo was captured at Palanan on March 23, 1901 and was brought back to Manila. Convinced of the futility of further resistance, he swore allegiance to the United States and issued a proclamation calling on his compatriots to lay down their arms. Yet insurgent resistance continued in various parts of the Philippines. *

Although the war continued into 1902, Aguinaldo's capture in 1901 signaled a turning point. The rebellion lost momentum after Aguinaldo encouraged his supporters to stop fighting and proclaimed his allegiance to the United States,. Though some fighting continued for the next four or five years, the United States had secured the islands. [Source: Dictionary of American History, Gale Group Inc., 2003]

The war was declared over by Theodore Roosevelt in July 1902 after most of the Philippines was captured. Funton became an American hero and Aguinaldo was placed under house arrest in Manila for more than a year. Not everyone was pleased the result. William Jennings Bryant said, "We cannot administer an empire in the Orient and maintain a republic in America." One former abolitionist called Aguinaldo "a brave patriot and lover of liberty hunted down by troops of a powerful nation, professed champion of self government." The fighting continued for several more years and didn't completely stop until 1905. According to some estimated by that time 600,000 people had died.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Library of Congress, Philippines Department of Tourism, Philippines government websites, Encyclopedia.com, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Wikipedia, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, UNESCO, National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) the official government agency for culture in the Philippines), Lonely Planet Guides, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, The Conversation, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Google AI, and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026