SPANISH ARRIVE IN THE PHILIPPINES

Named after King Phillip II of Spain, the Philippines was the main outpost in Asia for Spain, which had the majority of its empire in the New World, particularly Peru and Mexico. The Philippines was visited by Magellan— an "able and ruthless" Portugese soldier-adventurer-seaman with battle-lame leg employed by the Spanish — and was formally claimed by the Spaniard Miguel Lopez de Legazpi (also spelled Legaspi). Over the years missionaries introduced Christianity and tried to unify people, who had different languages and ethnic backgrounds, under a central government based in Manila.

The Philippines was an important acquisition for Spain, which at the time was competing with Portugal for control of the major trade routes from Asia and the New World to Europe. Philippine colonial history was often influenced more by events in Europe than in the archipelago. Portugal's claim on the islands was halted when Spain annexed Portugal in 1580. Holland declared independence from Spain in 1581, which led the growth of Dutch influence in Spice islands and the Dutch East Indies south of the Philippines. Spanish in the Philippines fought off attacks from the Dutch and the English. Manila was briefly occupied by the British, from 1762 to 1764.

The Spanish left the Philippines with an education system, the Roman Catholic religion, the Roman alphabet, private ownership of land, the Gregorian calendar, egalitarian Christian doctrine, unequal distribution of wealth, global consciousness, and various New World plants such as cassava, maize, and sweet potatoes.

Ferdinand Magellan was the first European recorded to have landed in the Philippines. He arrived in March 1521 during his circumnavigation of the globe. He claimed land for the king of Spain but was killed by a local chief. Following several more Spanish expeditions, the first permanent settlement was established in Cebu in 1565. After defeating a local Muslim ruler, the Spanish set up their capital at Manila in 1571, and they named their new colony after King Philip II of Spain. In doing so, the Spanish sought to acquire a share in the lucrative spice trade, develop better contacts with China and Japan, and gain converts to Christianity. Only the third objective was eventually realized. As with other Spanish colonies, church and state became inseparably linked in carrying out Spanish objectives. Several Roman Catholic religious orders were assigned the responsibility of Christianizing the local population. The civil administration built upon the traditional village organization and used traditional local leaders to rule indirectly for Spain. Through these efforts, a new cultural community was developed, but Muslims (known as Moros by the Spanish) and upland tribal peoples remained detached and alienated. [Source: Library of Congress *]

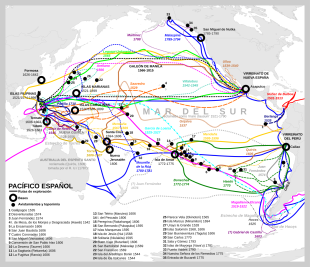

Trade in the Philippines centered around the “Manila galleons,” which sailed from Acapulco on the west coast of Mexico (New Spain) with shipments of silver bullion and minted coin that were exchanged for return cargoes of Chinese goods, mainly silk textiles and porcelain. There was no direct trade with Spain and little exploitation of indigenous natural resources. Most investment was in the galleon trade. But, as this trade thrived, another unwelcome element was introduced—sojourning Chinese entrepreneurs and service providers. *

RELATED ARTICLES:

PHILIPPINES BEFORE THE ARRIVAL OF THE SPANISH factsanddetails.com

PRE-COLONIAL FILIPINO STATES factsanddetails.com

MAGELLAN IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

CHRISTIANIZATION OF THE PHILIPPINES: MISSIONARIES, SUCCESS, FRIAROCRACY factsanddetails.com

PHILIPPINES UNDER SPANISH RULE: LIFE, COLONIZATION, CHINESE factsanddetails.com

TRADE AND PLANTATIONS IN THE PHILIPPINES UNDER THE SPANISH factsanddetails.com

MANILA GALLEONS: SPANISH TRADE BETWEEN THE PHILIPPINES AND MEXICO factsanddetails.com

MOROS: MUSLIMS IN MINDANAO AND THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF MUSLIMS IN THE SOUTHERN PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

Spanish Expeditions to the Philippines After Magellan

After Magellan thee Spanish expeditions led by Juan García Jofre de Loaysa (1526), Alvaro de Saavedra Cerón (1528), and Ruy López de Villalobos (1543) tried unsuccessfully to launch a colony in the archipelago. It was not until 1565 that Miguel Lopez De Legazpi succeeded. Villalobos renamed the islands after the heir to the Spanish throne, Philip, Charles I's son. [Source: Nicholas P. Cushner, Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, Gale, 2008]

Villalobos (c. 1500–1546) was a Spanish explorer who attempted to establish Spanish control over the Philippines in 1543 under the terms of the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) and the Treaty of Zaragoza (1529). He led an expedition with six ships that left from the west coast of Mexico. The expedition was able to reach the Philippines okay but failed in setting up a colony and making it back to Mexico because the crew of 370 men could not secure enough food through trade, farming, or raiding, and they were unable to obtain reinforcements from New Spain due to limited knowledge of Pacific winds and currents. Forced to abandon the mission, Villalobos retreated to the Portuguese-controlled Moluccas, where he was imprisoned and later died. He reportedly only named the islands of Leyte and Samar “Las Islas Filipinas”. That was eventually applied to the entire Philippine archipelago.

Philip, as King Philip II, sent a fresh fleet led by the Spanish Conquistador Miguel Lopez de Legazpi to the islands in the mid-16th century with strict orders to colonise and Catholicise. In 1565 an agreement was signed by Legazpi and Tupas, the defeated chief of Cebu, which made every Filipino answerable to Spanish law. [Source: Lonely Planet]

Miguel López de Legazpi

Miguel López de Legazpi was a low-level Spanish official in New Spain (Mexico). He captained a small fleet of ships led by the “San Pedro” that set out from New Spain in February 1565 and reached Gamay Bay off Samar Island, then proceeded to Leyte, Camiguin, and Bohol before finally reaching Cebu in April 1565. One of his ships made the critical discovery of the route from the Philippines to Mexico. Other Spaniards, including Ruy Lopez de Villalobos, had made it to the Philippines from Mexico but were unable to get back. [Source: Nicholas P. Cushner, Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World. Gale Group Inc., 2004]

Legazpi arrived with 400 settlers and a group of friars. Some say the Philippines was formally established as a Spanish colony when Legazpi and Sikatuna, the chief on the island of Bohol, signed a treaty with their own blood. Legazpi established the first permanent settlement, called San Miguel, on Cebu. He reached Panay in 1569 and Manila in 1571 and died 1572.

Under Legazpi the Spanish quickly established leadership over the many small, independent communities that had previously known no central rule. According to Lonely Planet: “Legazpi, his soldiers and a band of Augustinian monks wasted no time in establishing a settlement where Cebu City now stands; Fort San Pedro is a surviving relic of the era. First called San Miguel, then Santisimo Nombre de Jesus, this fortified town hosted the earliest Filipino-Spanish Christian weddings and, critically, the baptisms of various Cebuano leaders. Panay Island's people were beaten into submission soon after, with Legazpi establishing a vital stronghold there (near present-day Roxas) in 1569. [Source: Lonely Planet =]

Legazpi consolidated Spanish power in the Philippines and designated Manila as the capital. By 1571, when López de Legazpi founded Manila on the ruins of a conquered Moro town, the Spanish had secured their foothold in the Philippines, despite opposition from the Portuguese, who were eager to maintain their monopoly on East Asian trade. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Spain Sets Up Shop and Takes Control of the Philippines

The first Spanish settlement and Catholic mission in the Philippines was founded on Cebu in 1565. In May 1571, realizing that they could not sustain their colony in Cebu in the central Philippines, the group of Spanish settlers moved north to Manila and began building a fortified city on Manila Bay, which has a world class harbor and is accessible to the open Pacific Ocean and Asia. Juan de Salcedo led an expedition to conquer the area around Laguna de Bay and the Cagayan River. Martín de Goiti and one hundred soldiers penetrated the center of Luzon Island. [Source: Nicholas P. Cushner, Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World. Gale Group Inc., 2004]

After 1571, Manila became the center of Spanish colonization. The city quickly attracted merchants who made a major trading center. The original Spanish motivations for occupying the Philippines were to control the spice trade and the Pacific trade routes. However, the Philippines were too far from the spice routes, and other European powers never recognized Spanish dominance in the Pacific.

Portugal did not really make an effort to colonize the Philippines primarily due to its strategic focus on established, lucrative trade routes in the Indian Ocean and the Spice Islands (Moluccas), rather than territorial acquisition in Southeast Asia. The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas divided the world between Portugal and Spain. The 1529 Treaty of Zaragoza (or Saragossa) placed the Philippines within the Portuguese sphere of influence, not Spanish, by establishing a line of demarcation 297.5 leagues east of the Moluccas. Although Spain technically sold its rights to the area to Portugal, Spain ignored the treaty and colonized the Philippines in 1565.

The Sultanates of Maguindanao of Sulu in what is now the southern Philippines traded and maintained good relations with the Chinese, Dutch, and the British. The Spanish military fought off several external challenges, especially from the British, Dutch, and Portuguese and Chinese pirates.

The first Dutch squadron to reach the Philippines was led by Olivier van Noort. In December 1600, van Noort's squadron grappled with the Spanish fleet under Antonio de Morga near Fortune Island, where de Morga's flagship, the San Diego, sank. The British briefly occupied Manila between 1762 and 1764.

Why the Spanish Took Over the the Philippines So Easily

The Spanish and Portuguese were able to establish their large empires in Asia because they encountered virtually no resistance. The Sultans in Malaysia and Indonesia were easy to overcome, Filipinos were just tribal farmers, and the Monghols in India didn't have much of a navy. The Portuguese and Spanish established themselves by building forts and trading out of them. The Dutch later moved in and took possession of many of the Portuguese forts by force, which in turn were taken away from them by the English. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

"Portuguese galleons," historian K.N. Chaudhuri told Severy, "maximized the advantages of Europe's gunpowder revolution and artillery. With an added deck and gunports, the galleon became a floating fortress and floating warehouse." [Source: Merle Severy, National Geographic, November 1992]

Professor Susan Russell wrote: At the time the Spanish arrived “ almost nothing was known of the Philippines, and so our sources of information about pre-Hispanic societies in the country date from the early period of Spanish contact. Most Philippine communities, with the exception of the Muslim sultanates in the Sulu archipelago and Mindanao, were fairly small without a great deal of centralized authority. Authority was wielded by a variety of individuals, including 1) headmen, or datu; 2) warriors of great military prowess; and 3) individuals who possessed spiritual power or magical healing abilities. [Source: Professor Susan Russell, Department of Anthropology, Center for Southeast Asian Studies Northern Illinois University, seasite.niu.edu]

The absence of centralized power meant that a small number of Spaniards were able to convert a large number of Filipinos living in politically autonomous units more easily than they could have, say, converted people living in large, organized, complex kingdoms such as those Hinduized or (later) Theravada Buddhist-influenced kingdoms in mainland Southeast Asia and on the island of Java in Indonesia. The Spanish were unsuccessful in converting Muslim Sultanates to Christianity, and in fact warred with Muslim Filipinos throughout their 300 year colonial rule from 1521 - 1898. Nor did they successfully conquer certain highland areas, such the Luzon highlands, where a diverse array of ethno-linguistic groups used their remote, difficult mountainous terrain to successfully avoid colonization.

Nuestra Señora de Guia (Our Lady of Guidance)

Our Lady of Guidance (Spanish: Nuestra Señora de Guia) is a 16th-century Roman Catholic image of the Blessed Virgin Mary as the Immaculate Conception that is widely venerated by Filipino Roman Catholics. Considered to be a form of Black Madonna, the wooden statue is considered the oldest artistic depiction of Mary in the Philippines, and is believed to have been originally brought to the islands by Ferdinand Magellan (along with Santo Niño de Cebú) in the early 16th century. Locally venerated as patroness of navigators and travellers, the image is enshrined in the Nuestra Señora de Guia Archdiocesan Parish in Ermita, City of Manila. The venerated image is often framed the Pandan leaves associated with her primeval discovery by early Filipino pagans. [Source: Wikipedia]

Nuestra Señora de Guia is regarded as the Patroness of Overseas Filipino Workers. Made of molave (Vitex cofassus) wood, the icon stands at about 50 centimetres, and is characterised by dark skin and Chinese facial features. Its head has a wig of long, light brown hair and is dressed in both a manto and a stylised tapis, the traditional wraparound skirt of pre-Hispanic Filipino women. Among its regalia are a marshal's baton; a set of jewels given by Archbishop of Manila Cardinal Rufino Santos in 1960; and a golden crown donated by Pope Paul VI during his visit to Manila Cathedral on 16 May 1971. When the Shrine celebrates the image's feast every 19 May, it prohibits the original statue from being borne in procession in order to preserve it. A replica is instead brought out into the city streets for public veneration whilst the original remains ensconced in its glass alcove above the high altar.

According to the Anales de la Catedral de Manila, the crew of Miguel López de Legaspi discovered along the seaside of what is now Ermita a group of animist natives worshipping a statue of a female figure, later identified as the Virgin Mary. Later accounts claimed the statue was brought by Ferdinand Magellan in 1521 and was given as a gift to a chieftain of Cebu.[3] Local folklore meanwhile recounts the Spaniards witnessing natives venerate the statue, which was placed on a trunk surrounded by pandan plants. This is remembered today by the placement of real or imitation pandan leaves around the image's base as one of its iconic attributes. The statue is notable for her narrow, almond-shaped eyes, which some consider evidence of a Chinese origin for the statue.

On 19 May 1571 the indigenous kings Rajah Sulaiman III and Rajah Matanda ceded the Kingdom of Maynila to the Spanish, with Legaspi co-consecrating the city to Saint Pudentiana. In 1578, Phillip II of Spain issued a royal decree invoking Our Lady of Guidance to be "sworn patroness" of Manila, making her the city's titular patroness. The statue was initially enshrined at Manila Cathedral until 1606, when the original parish compound was built. Called La Hermita ("The Hermitage"), it was constructed using bamboo, nipa, and molave wood. It was later rebuilt with cement but was heavily damaged by an earthquake in 1810.

Chinese and Spanish in Early Colonial Philippines

When the Spaniards began colonizing Manila, they found an established Chinese settlement already in place. Throughout the Spanish colonial period, the colonizers—though cautious and often suspicious of the Chinese—relied heavily on their skills. Chinese craftsmen were instrumental in constructing churches and grand houses, and they were renowned furniture makers. The country’s oldest stone church, San Agustin Church (16th century), still features a choir loft and carved chairs created by Chinese artisans in Canton, while Chinese stone lions stand along its churchyard walls. Much of the Spanish-era religious imagery, known as santos, also reflects Chinese artistic influence, including stylized cloud patterns in paintings and carvings and almond-shaped eyes in depictions of saints. [Source: “Culture Shock!: Philippines” by Alfredo Roces and Grace Roces, Marshall Cavendish International, 2010]

Wealthy Chinese settlers often intermarried with members of the local ruling class, forming a Filipino-Chinese mestizo elite that became prominent in political and social life. Several major Filipino figures had Chinese ancestry, including national hero Jose Rizal, revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo, and Commonwealth president Sergio Osmeña. Former president Corazon Aquino also acknowledged Chinese lineage.

Despite this integration, Spanish authorities remained wary of the Chinese community, and their rule was marked by periodic but systematic massacres. Western colonial attitudes contributed to the growth of anti-Chinese sentiment among some Filipinos. Many Chinese migrants, who arrived impoverished and determined to endure hardship for economic opportunity, were viewed by some as aggressive competitors focused solely on business. Others criticized their limited knowledge of local languages and their frugal lifestyles, interpreting these traits as signs of inferiority. As a result, derogatory stereotypes emerged in popular culture, where folk tales, plays, and songs often portrayed the Chinese as sinister or comical figures.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Library of Congress, Philippines Department of Tourism, Philippines government websites, Encyclopedia.com, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Wikipedia, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, UNESCO, National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) the official government agency for culture in the Philippines), Lonely Planet Guides, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, The Conversation, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Google AI, and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026