SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR (APRIL TO DECEMBER 1898)

The Spanish-American War (April to December 1898) should be called Spanish-American-Cuban-Philippine War because Cuba is where much of the action took place and the Philippines was affected the most by its outcome. Spain was pushed into the war after the sinking of the U.S. ship the Maine in Cuba, which killed 260 officers and men, but the Spanish actually had nothing to do with. Among those who reported on the war were Mark Twain, who “expertly excoriated” it .

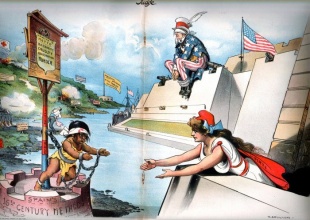

The eight-month war established the United States as a global power. Fought on two continents, it had a number of big events for the US military and led to the independence of Cuba (which the U.S. dominated afterwards) and to U.S. control of Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam. The Spanish-American War was conducted under U.S. President William McKinley, who was known mainly as a ditherer. At first, like most Americans, he didn't even known where the Philippines was. The conflict spilled form Cuba into the Philippines because the United States realized the weakness of Spain and figured why stop at Cuba, why not seize all of Spain's possessions, which included the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Guam.

The Spanish-American War was pushed by Assistant Secretary of the Navy Teddy Roosevelt and Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, who were intent on making the United States a world power. Roosevelt evoked a "superior people theory" to justify American incursions in Cuba and the Philippines and said "the most ultimately righteous of all wars is a war with savages" which establishes "the foundations for the future greatness of a mighty people."

Roosevelt called the Filipinos "Tagal bandits," Malay bandits," "Chinese half-breeds," and "savages, barbarians, a wild and ignorant people, Apaches, Sioux, Chinese Boxers." Other American leaders called the Filipinos "a drunken uncontrollable mob" with "the minds of children" who were "waging a war not against tyranny, but against Anglo-Saxon order and decency." The Filipino rebel leader Emilio Aguinaldo was called "a cold blooded murderer and would-be dictator."

RELATED ARTICLES:

U.S. TAKES OVER THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

DECLINE OF THE SPANISH IN THE PHILIPPINES AND RISE FILIPINO NATIONALISM factsanddetails.com

JOSE RIZAL’S EXECUTION AND FILIPINO ACTIVISM AND REBELLIONS AGAINST SPAIN factsanddetails.com

THE PHILIPPINES: THE UNITED STATES’ FIRST COLONY factsanddetails.com

PHILIPPINES ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE UNDER THE UNITED STATES factsanddetails.com

JAPAN TAKES THE PHILIPPINES: ATTACK, FIGHTING, MACARTHUR, CORREGIDOR factsanddetails.com

JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF THE PHILIPPINES: BATAAN DEATH MARCH, PUPPET STATE, RESISTANCE factsanddetails.com

BATTLE OF LEYTE: LAND AND SEA FIGHTING, MACARTHUR, BATTLESHIPS factsanddetails.com

BATTLE OF MANILA IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com

DEFEAT OF JAPAN IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

'Splendid Little War' That Made the U.S. a World Power

It is hard to imagine a war described as “splendid,” yet that is how John Hay characterized America’s 1898 conflict with Spain. A close friend of Theodore Roosevelt, Hay celebrated the swift U.S. victory, achieved with relatively few American battle deaths and resulting in new overseas territories. The Spanish-American War, fought over just four months in 1898, marked the United States’ emergence as a global power. After the fighting, Hay praised Roosevelt—who had led the volunteer cavalry known as the Rough Riders—calling it “a splendid little war” waged with noble motives and bold spirit. [Source: Michael Richman, Washington Post, April 8, 1998]

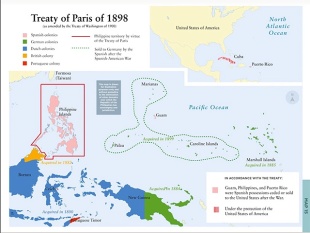

The war dismantled much of Spain’s centuries-old empire. The United States seized Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, while also annexing Hawaii amid rising expansionist fervor. President William McKinley justified the move in the language of Manifest Destiny, the belief that Americans were divinely ordained to expand their influence. Prominent leaders such as Roosevelt and Senator Henry Cabot Lodge argued that great powers required empires. Spain’s colonial weakness offered the opportunity. Historians later observed that the United States, brimming with economic and military confidence, was eager to prove itself on the world stage.

The conflict began against the backdrop of Cuba’s 1895 rebellion against Spanish rule. Reports of Spanish brutality—often exaggerated by sensationalist newspapers owned by Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst—fueled public outrage through “yellow journalism.” The mysterious explosion of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor in February 1898, which killed more than 250 sailors, intensified calls for intervention. Though the cause was never conclusively proven, headlines blamed Spain, and the rallying cry “Remember the Maine!” swept the nation. By April, war had been declared.

The first major battle occurred far from Cuba at the Battle of Manila Bay in the Philippines. Commodore George Dewey destroyed the Spanish fleet with no American combat deaths, instantly becoming a national hero. In the Caribbean, U.S. naval forces defeated Spain again at the Battle of Santiago. On land, Roosevelt’s Rough Riders gained fame charging Kettle Hill, while African American soldiers of the 10th Cavalry played a crucial and often underrecognized role in capturing San Juan Hill. Spain surrendered Santiago in July, and an armistice followed in August.

The Treaty of Paris formally ended the war in December 1898. Spain relinquished Cuba and ceded Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines to the United States, which paid $20 million for the latter. Although only 385 Americans died in battle, thousands more succumbed to disease. Fighting continued in the Philippines until 1902 against independence fighters, at far greater human cost. The war reshaped global power, propelled Roosevelt to national prominence, and marked the United States’ decisive entry into imperial politics—an outcome far more complex than Hay’s phrase “splendid little war” suggested.

Outbreak of the Spanish-American War in Cuba in 1898

Spain's rule in the Philippines came to an end as a result of United States involvement with Spain's other major colony, Cuba. American business interests were anxious for a resolution — with or without Spain — of the insurrection that had broken out in Cuba in February 1895. Moreover, public opinion in the United States had been aroused by newspaper accounts of the brutalities of Spanish rule.

Cuba was the focus of dispute between Spain and the U.S. over sugar. U.S. showed interest in purchasing Cuba long before 1898. Following the Ten Years War (1868-1878), when Cuban guerrilla fighters known as mambises fought for autonomy from Spain, American sugar interests bought up large tracts of land in Cuba. Alterations in the U.S. sugar tariff favoring home-grown beet sugar helped foment the rekindling of revolutionary fervor in 1895. By that time the U.S. had more than $50 million invested in Cuba and annual trade, mostly in sugar, was worth twice that much. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Tensions between Spain and the United States also rose out of the attempts by Cubans to liberate their island from the control of the Spanish. The first Cuban insurrection was unsuccessful and lasted between 1868 and 1878. American sympathies were with the revolutionaries, and war with Spain nearly erupted when the filibuster ship Virginius was captured and most of the crew (including many American citizens) were executed. The Cuban revolutionaries continued to plan and raise support in the United States. [Source: U.S. Navy]

The second bid for independence by Cuban revolutionaries began in April 1895. The Spanish government reacted by sending General Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau with orders to pacify the island. The "Butcher," as he became known in the U.S., determined to deprive the rebels of support by forcibly reconcentrating the civilian population in the troublesome districts to areas near military headquarters. This policy resulted in the starvation and death of over 100,000 Cubans. Outrage in many sectors of the American public, fueled by stories in the "Yellow Press," put pressure on Presidents Grover Cleveland and William McKinley to end the fighting in Cuba. American diplomacy, along with the return of the Liberal Party to power in Spain, led to the recall of General Weyler. However, beset by political enemies at home, the new Spanish government was too weak to enact meaningful reforms in Cuba. Limited autonomy was promised late in 1897, but the U.S. government was mistrustful, and the revolutionaries refused to accept anything short of total independence. [Ibid]

Fervor for war had been growing in the United States, despite President Grover Cleveland's proclamation of neutrality on June 12, 1895. But sentiment to enter the conflict grew in the United States when General Valeriano Weyler began implementing a policy of Reconcentration that moved the population into central locations guarded by Spanish troops and placed the entire country under martial law in February 1896. By December 7, 1896 President Cleveland reversed himself declaring that the United States might intervene should Spain fail to end the crisis in Cuba. U.S. President William McKinley, inaugurated on March 4, 1897, was even more anxious to become involved, particularly after the New York Journal published a copy of a letter from Spanish Foreign Minister Enrique Dupuy de Lôme criticizing the American President on February 9, 1898. Events moved swiftly after the explosion aboard the U.S.S. Maine on February 15. On March 9, Congress passed a law allocating fifty million dollars to build up military strength. On March 28, the U.S. Naval Court of Inquiry finds that a mine blew up the Maine. On April 21 President McKinley orders a blockade of Cuba and four days later the U.S. declared war. *

The war began with two American successes. Admiral William Sampson immediately established a blockade of Havana that was soon extended along the north coast of Cuba and eventually to the south side. Sampson then prepared to counter Spanish effort to send naval assistance. Then, on 1 May, Commodore George Dewey, commanding the Asiatic Squadron, destroyed Admiral Patricio Montoyo's small force of wooden vessels in Manila Bay. *

Sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor

The blowing up of the battleship USS Maine in Havana harbor on the evening of 15 February, 1898 was a critical event on the road to that war. When pro-Weyler forces in Havana instigated riots in January 1898, Washington became greatly concerned for the safety of Americans in the country. The administration believed that some means of protecting U.S. citizens should be on hand. On 24 January, President McKinley sent the second class battleship USS Maine from Key West to Havana, after clearing the visit with a reluctant government in Madrid. [Source: U.S. Navy ^]

The battleship arrived on 25 January. Spanish authorities in Havana were wary of American intentions, but they afforded Captain Charles Sigsbee and the officers of Maine every courtesy. In order to avoid the possibility of trouble, Maine's commanding officer did not allow his enlisted men to go on shore. Sigsbee and the consul at Havana, Fitzhugh Lee, reported that the Navy's presence appeared to have a calming effect on the situation, and both recommended that the Navy Department send another battleship to Havana when it came time to relieve Maine. ^

At 9:40 on the evening of 15 February, a terrible explosion on board Maine shattered the stillness in Havana Harbor. Later investigations revealed that more than five tons of powder charges for the vessel's six and ten-inch guns ignited, virtually obliterating the forward third of the ship. The remaining wreckage rapidly settled to the bottom of the harbor. Most of Maine's crew were sleeping or resting in the enlisted quarters in the forward part of the ship when the explosion occurred. Two hundred and sixty-six men lost their lives as a result of the disaster: 260 died in the explosion or shortly thereafter, and six more died later from injuries. Captain Sigsbee and most of the officers survived because their quarters were in the aft portion of the ship. Spanish officials and the crew of the civilian steamer City of Washington acted quickly in rescuing survivors and caring for the wounded. The attitude and actions of the former allayed initial suspicions that hostile action caused the explosion, and led Sigsbee to include at the bottom of his initial telegram: "Public opinion should be suspended until further report." ^

The U.S. Navy Department immediately formed a board of inquiry to determine the reason for Maine's destruction. The inquiry, conducted in Havana, lasted four weeks. The condition of the submerged wreck and the lack of technical expertise prevented the board from being as thorough as later investigations. In the end, they concluded that a mine had detonated under the ship. The board did not attempt to fix blame for the placement of the device. ^

When the Navy's verdict was announced, the American public reacted with predictable outrage. Fed by inflammatory articles in the "Yellow Press" blaming Spain for the disaster, the public had already placed guilt on the Spanish government. Although he continued to press for a diplomatic settlement to the Cuban problem, President McKinley accelerated military preparations begun in January 1898 when an impasse appeared likely. The Spanish position on Cuban independence hardened, and McKinley asked Congress on 11 April for permission to intervene. On 21 April, the President ordered the Navy to begin a blockade of Cuba, and Spain followed with a declaration of war on 23 April. Congress responded with a formal declaration of war on 25 April, made retroactive to the start of the blockade. ^

The destruction of Maine did not cause the U.S. to declare war on Spain, but it served as a catalyst, accelerating the approach to a diplomatic impasse. In addition, the sinking and deaths of U.S. sailors rallied American opinion more strongly behind armed intervention. In 1911 the Navy Department ordered a second board of inquiry after Congress voted funds for the removal of the wreck of Maine from Havana Harbor. U.S. Army engineers built a cofferdam around the sunken battleship, thus exposing it, and giving naval investigators an opportunity to examine and photograph the wreckage in detail. Finding the bottom hull plates in the area of the reserve six-inch magazine bent inward and back, the 1911 board concluded that a mine had detonated under the magazine, causing the explosion that destroyed the ship. ^

Technical experts at the time of both investigations disagreed with the findings, believing that spontaneous combustion of coal in the bunker adjacent to the reserve six-inch magazine was the most likely cause of the explosion on board the ship. In 1976, Admiral Hyman G. Rickover published his book, How the Battleship Maine Was Destroyed. The admiral became interested in the disaster and wondered if the application of modern scientific knowledge could determine the cause. He called on two experts on explosions and their effects on ship hulls. Using documentation gathered from the two official inquiries, as well as information on the construction and ammunition of Maine, the experts concluded that the damage caused to the ship was inconsistent with the external explosion of a mine. The most likely cause, they speculated, was spontaneous combustion of coal in the bunker next to the magazine. ^

Some historians have disputed the findings in Rickover's book, maintaining that failure to detect spontaneous combustion in the coal bunker was highly unlikely. Yet evidence of a mine remains thin and such theories are based primarily on conjecture. Despite the best efforts of experts and historians in investigating this complex and technical subject, a definitive explanation for the destruction of Maine remains elusive. ^

Spanish-American War in the Philippines

When the United States declared war on Spain on April 25, 1898, acting Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt ordered Commodore George Dewey, commander of the Asiatic Squadron, to sail to the Philippines and destroy the Spanish fleet anchored in Manila Bay. The Spanish navy, which had seen its apogee in the support of a global empire in the sixteenth century, suffered an inglorious defeat on May 1, 1898, as Spain's antiquated fleet, including ships with wooden hulls, was sunk by the guns of Dewey's flagship, the Olympia, and other United States warships. More than 380 Spanish sailors died, but there was only one American fatality. [Source: Library of Congress *]

As Spain and the United States had moved toward war over Cuba in the last months of 1897, negotiations of a highly tentative nature began between United States officials and Aguinaldo in both Hong Kong and Singapore. When war was declared, Aguinaldo, a partner, if not an ally, of the United States, was urged by Dewey to return to the islands as quickly as possible. Arriving in Manila on May 19, Aguinaldo reassumed command of rebel forces. Insurrectionists overwhelmed demoralized Spanish garrisons around the capital, and links were established with other movements throughout the islands. *

In the eyes of the Filipinos, their relationship with the United States was that of two nations joined in a common struggle against Spain. As allies, the Filipinos provided American forces with valuable intelligence (e.g., that the Spanish had no mines or torpedoes with which to sink warships entering Manila Bay), and Aguinaldo's 12,000 troops kept a slightly larger Spanish force bottled up inside Manila until American troop reinforcements could arrive from San Francisco in late June. Aguinaldo was unhappy, however, that the United States would not commit to paper a statement of support for Philippine independence. *

Dewey and Manila Bay

On May 1, 1898, an American navy fleet commanded by Admiral Dewey destroyed the entire Spanish fleet in Manila Bay and, with the help of Filipino rebels, forced the Spanish army holed up in Intramuros fortress to surrender. Dewey, who was 60 at the time of the battle, had never distinguished himself in fighting before. He served in the Civil War but didn't see any action and for many years he was in charge of the country's lighthouses. Dewey was a vain man who wore sharp clothes and devoted much attention to his mustache. The main thing he had going for him was a friendship with Teddy Roosevelt. [Source: Ralph Graves, Smithsonian, March 1992]

Dewey was in Hong King when the “Maine” was sunk on February 25, 1897. Roosevelt cabled him, "Keep full of coal. In the event declaration of war Spain, your duty will be to see that the Spanish squadron does not leave the Asiatic coast, and then offensive operations in Philippine Islands.." After Congress declared war on April 23, Dewey was ordered to: "Proceed at once to Philippines. Commence Operations against the Spanish Squadron. You must capture or destroy. Use utmost endeavors."

Dewey had never been to the Philippines and based his battle strategy on reports from people who had visited the islands. He commanded six ships with 53 guns against a Spanish fleet of seven ships with 31 guns with a shorter range than the American guns as well fortifications with 17 guns on three island at the entrance of Manila Bay. The channels into Manila Bay were rumored to be mined. Inside the bay, the Spanish had 37 shore batteries.

Battle of Manila Bay

Dewey guessed correctly that danger of mines was "negligible" and slipped by the fortifications at the entrance of Manila Bay at night while the guards and gunnners were sleeping at their posts. The fortification at El Friale got off four shots. The batteries at Corregidor and Cabaalo delivered “none at all."

The Spanish commander, Adm. Patrico Montojo, had requested backup and more supplies from Spain but they never arrived. When news arrived that the Americans were in Manila Bay, he positioned his forces at the southern end of the bay in a place called Cavite, reportedly to spare Manila the shelling from an attack and because the waters there were shallow enough that his men could escape with their lives if the ships were sunk.

The sea battle lasted only three hours. Not a single American was killed by enemy fire and only eight were wounded, none seriously. In contrast 381 Spaniards were killed or wounded. Dewey moved his ships to a range from the Spanish ships where his guns could hit their ships but their guns couldn't hit his. He gave the order, "you may fire when you are ready," and the American ships pounded away and found their mark at a distance of 2,000 yards. All but one of Spanish ships were sunk. Only one American ship was hit and it remained afloat with no deaths.

The sinking of the Spanish fleet meant that 15,000 Spanish soldiers were holed up in Intramuros— the Walled City of Manila—cut off from supplies and reinforcements. Three months later 11,000 American soldiers were in the Philippines and the 250,000 people in Manila were starving and sick. Their water supply had been cut off and people were eating horses and cats.

Messages were sent back and forth between Dewey and the Spanish commander in Manila, General Fermin Jaudenes. A face-saving charade was worked out that the Americans would "attack" the fortification of Manila and the Spanish surrender. At 9:35am on August 13, 1898, American forces sent shells flying in the direction of Spanish positions but as planned none caused any serious damage. At 11:20 Jaudenes raised a white flag in surrender. Six Americans were killed in various accidents.

George Dewey provided Emilio Aguinaldo with weapons and encouraged him to mobilize Filipino forces against Spain. By the time American ground troops reached the Philippines, Filipino revolutionaries had secured control of nearly all of Luzon, leaving only the historic walled city of Manila under Spanish control and under siege. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Capture of Guam During the Spanish-American War on the Pacific

Guam was taken without a fight during the Spanish-American. Indeed, the Spanish on the island had didn’t even know they were at war. Benjamin Brimelow wrote in Business Insider: In the 1898, the big prize for Spain and the US in the Pacific was the Philippines. Guam was an important stop between the Americas and the Philippines, but neither Spain nor the US paid much attention to it. The Americans had already positioned Commodore George Dewey's Asiatic Squadron off China in anticipation of striking the Spanish fleet at Manila. But after a May 9 meeting of the US Navy War Board, which was formed to develop a strategy for the war, it was decided that Guam should also be taken to support operations in the Philippines.[Source: Benjamin Brimelow, Business Insider, June 29, 2021]

“To seize it, Secretary of the Navy John Long issued sealed orders to Capt. Henry Glass of the USS Charleston, a protected cruiser en route from California to Manila. In Honolulu, Charleston was joined by three troop transports. As instructed, Glass only read his orders after leaving Hawaii on June 4. "You are hereby directed to stop at the Spanish Island of Guam," the orders read. "You will use such force as may be necessary to capture the port of Guam, making prisoners of the Governor and other officials, and any armed force that may be there." Glass was also ordered to destroy any Spanish fortifications or naval vessels he encountered.

Though the orders said the operation "should not occupy more than one or two days," Guam's defenses were not entirely known, so while en route Charleston's crew spent days firing on practice targets in the ocean. Charleston arrived off Guam on the morning of June 20. Encountering only an abandoned fort and no Spanish ships in Agana, the capital city, Glass ordered his ship to sail to Apra Harbor. To the crew's disappointment, the only vessel there was a Japanese trading ship. Charleston fired several shots at Fort Santa Cruz to see if it was occupied, but it was also abandoned.

“Spanish officials soon sailed out to meet Charleston in two small boats, one of which had a US flag on its topsail. Upon boarding the Charleston, the Spaniards apologized. They had interpreted Charleston's gunfire as a salute, and they told the Americans they could not respond in kind because of a lack of gunpowder. It turned out the island hadn't communicated with Manila since April 14 — 11 days before the US declared war on Spain — and no Spanish Navy vessel had visited Guam in 18 months.

“Glass told the Spaniards that their countries were at war and that he was taking over the island. He demanded Guam's governor, Don Juan Marina, surrender the island in person aboard Charleston. The delegation returned, and Marina requested to speak to Glass on the island instead, as he was not legally allowed to board a foreign warship. The next day, Glass sent an envoy to demand the Spanish surrender and gave them a half-hour to comply. Twenty-nine minutes later, Marina surrendered. The island's garrison, which had fewer than 60 men, was disarmed and taken as prisoners aboard one of the transport ships, as were Marina and other Spanish officials. The Americans then set sail for Manila, where they assisted Dewey for the rest of the war.

After the surrender, Glass personally examined Fort Santa Cruz, where he raised the American flag. “The fort itself "was entirely useless as a defensive work, with no guns and in a partly ruinous condition," Glass wrote in a report to Long. Glass described the other forts on the island as having "no value," and that the only guns that could be found were obsolete cast-iron guns used for saluting "but now condemned as unsafe even for that purpose."

While the Spanish had neglected Guam, the US turned it into an important base. The Japanese captured it on December 10, 1941, but the US retook it in a bloody 21-day battle in summer 1944, and used it as a base for B-29 bombing missions for the rest of the war. Guam is now home to roughly 170,000 people, and its importance for the US military has only increased. “It is now the US's "most critical operating location west of the international dateline," Adm. Philip Davidson said before retiring as head of US Indo-Pacific Command earlier this year.

Jockeying for Position After the Battle of Manila Bay

Keen to gain Filipino support, Dewey welcomed the return of exiled revolutionary General Aguinaldo and oversaw the Philippine Revolution mark II, which installed Aguinaldo as president of the first Philippine republic. The Philippine flag was flown for the first time during the proclamation of Philippine Independence on 12 June 1898.

But by late May, the United States Department of the Navy had ordered Dewey, newly promoted to Admiral, to distance himself from Aguinaldo lest he make untoward commitments to the Philippine forces. The war with Spain still was going on, and the future of the Philippines remained uncertain. The immediate objective was to capture Manila, and it was thought best to do that without the assistance of the insurgents. By late July, there were some 12,000 United States troops in the area, and relations between them and rebel forces deteriorated rapidly. [Source: Library of Congress *]

By the summer of 1898, Manila had become the focus not only of the Spanish-American conflict and the growing suspicions between the Americans and Filipino rebels but also of a rivalry that encompassed the European powers. Following Dewey's victory, Manila Bay was filled with the warships of Britain, Germany, France, and Japan. The German fleet of eight ships, ostensibly in Philippine waters to protect German interests (a single import firm), acted provocatively — cutting in front of United States ships, refusing to salute the United States flag (according to naval courtesy), taking soundings of the harbor, and landing supplies for the besieged Spanish. Germany, hungry for the ultimate status symbol, a colonial empire, was eager to take advantage of whatever opportunities the conflict in the islands might afford. Dewey called the bluff of the German admiral, threatening a fight if his aggressive activities continued, and the Germans backed down. *

The Spanish cause was doomed, but Fermín Jaudenes, Spain's last governor in the islands, had to devise a way to salvage the honor of his country. Negotiations were carried out through British and Belgian diplomatic intermediaries. A secret agreement was made between the governor and United States military commanders in early August 1898 concerning the capture of Manila. In their assault, American forces would neither bombard the city nor allow the insurgents to take part (the Spanish feared that the Filipinos were plotting to massacre them all). The Spanish, in turn, would put up only a show of resistance and, on a prearranged signal, would surrender. In this way, the governor would be spared the ignominy of giving up without a fight, and both sides would be spared casualties. The mock battle was staged on August 13. The attackers rushed in, and by afternoon the United States flag was flying over Intramuros, the ancient walled city that had been the seat of Spanish power for over 300 years. *

The agreement between Jaudenes and Dewey marked a curious reversal of roles. At the beginning of the war, Americans and Filipinos had been allies against Spain in all but name; now Spanish and Americans were in a partnership that excluded the insurgents. Fighting between American and Filipino troops almost broke out as the former moved in to dislodge the latter from strategic positions around Manila on the eve of the attack. Aguinaldo was told bluntly by the Americans that his army could not participate and would be fired upon if it crossed into the city. The insurgents were infuriated at being denied triumphant entry into their own capital, but Aguinaldo bided his time. Relations continued to deteriorate, however, as it became clear to Filipinos that the Americans were in the islands to stay. *

Deciding the Fate of the Philippines

Under the Treaty of Paris of December 10, 1898, which formally ended the Spanish-American War the Philippines—in addition to Cuba, Puerto Rico and Guam—were ceded to the United States, which "bought" the title for the Philippines from Spain for $20 million. The deal was between Spain and the United States. The people of the Philippines had no say in the matter.

After the Spanish surrendered there was debate in America about what to do with the Philippines: give them back to Spain, grant the islands independence, or claim them as a colony. Dewey had reported that the Filipino were ready for independence but later retracted the statement.

Pushed by Roosevelt, and business interests, U.S. President McKinley decided to keep the Philippines and announced it had been "benevolently assimilated." The Filipino upper class was happy with the peace treaty but the rebels who fought against Spain and declared Filipino independence were not.

Dewey stayed on in the Philippines for a year and lived like a sultan. When he returned to the United States in 1899 he was welcomed with a ticker tape parade and was given a special ceremonial sword by Congress.

Aftermath of the Spanish-American War on the Pacific

In 1565, Spain had claimed part of the Mariana Islands and extended its influence over Guam and Micronesia. Its main objective in controlling these islands was to provide waystation and back up of the the “Manila galleons,” which sailed between the Philippines and Acapulco on the west coast of Mexico (New Spain) with shipments of silver bullion and minted coins that were exchanged for return cargoes of Chinese goods, mainly silk textiles and porcelain. Spain formally claimed the Caroline Islands (Micronesia) and Mariana Islands in 1885 and retained them until 1899,

During the Spanish-American War, in 1898, the United States seized Guam. In 1899 following the Spanish-American War, the United States took Guam and the Philippines and the rest of Spain's interests were dissolved with their sale of the northern Marianas, the Carolines, and the Marshalls to Germany.

After the Spanish lost the Spanish-American War in 1898 they relinquished their clams on Micronesia by including Guam and Wake Island (and Cuba) in the $20 million purchase of the Philippines. The Carolines and the remainder of the Marianas was sold to the Germans for US$4.25 million.

Ignoring Spanish claims and operating out of New Guinea, the Germans had begun developing the copra trade in Micronesia in the mid 1800s. After 50 years in Micronesia, the Germans managed to make only small profits but they did force many islanders to move off their land and accept to Western ideas of land ownership. Germany lost its possessions to Japan in 1914 at the beginning of World War I. Japanese administration commenced at the end of World War I,

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Library of Congress, Philippines Department of Tourism, Philippines government websites, Encyclopedia.com, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Wikipedia, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, UNESCO, National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) the official government agency for culture in the Philippines), Lonely Planet Guides, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, The Conversation, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Google AI, and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026