MANILA GALLEONS

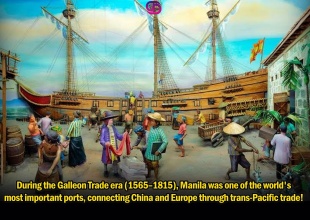

Trade in the Philippines centered around the “Manila galleons,” which sailed from Acapulco on the west coast of Mexico (New Spain) with shipments of silver bullion and minted coinage that were exchanged for return cargoes of Chinese goods, mainly silk textiles and porcelain. There was no direct trade with Spain and little exploitation of indigenous Philippines natural resources. Most investment was in the galleon trade. Among those who profited were sojourning Chinese entrepreneurs and service providers.

For 250 years, from 1565 to 1815, Spanish galleons shuttled between Acapulco and Manila, exchanging treasures of the West for those the East, making huge profits for the Spaniards. The trade has been described as “one of the most persistent, perilous and profitable commercial enterprises in European colonial history.” For a long period of time it was the “most significant pathway for commerce and cultural interchange between Europe and Asia.” [Source: Eugene Lyon, National Geographic, September 1990 ]

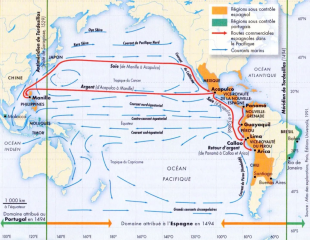

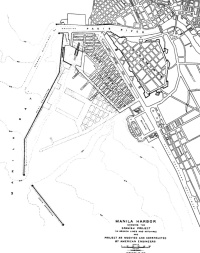

The trade was a monopoly and Manila was a trans-shipment center. Galleons shipped Oriental goods to Manila, from which they traveled to Acapulco in Mexico, and from there to the mother country — Spain. The galleons sailed once or twice. Sometimes they traveled in convoys but more often than not a single, massively large ship made the journey. A few vessels sailed from Manila directly to Spain rounding the Cape of Good Hope, but these voyages were soon stopped by their enemy the Dutch, who controlled this sea route.

Acapulco began as Spanish port from which goods received from the Orient were transported overland by mule to present day Mexico City and then to Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico, where the goods were reloaded on ships bound for Spain that rendezvoused with other Spanish ships in Havana for the trip to Spain. A little further north of Acapulco is Puerto Navidad, where the Spanish launched their conquest of the Philippines. Acapulco was selected as the trading port of the Manila galleons in the Americas because of its excellent harbor, and overland accessibility to Vera Cruz on the Caribbean side of Mexico.

The trade route between the Philippines and Mexico was opened in 1564 when the eastward route was discovered from the Philippines to Mexico by Legazpi. Beginning with Magellan navigators had sailed from Mexico to the Philippines for decades but were unable to find the route back. Many of the first conquistadors to arrive in the Philippines gave themselves up to their enemies the Portuguese because it was their way only to make it back to Europe.

Ellsworth Boyd wrote in “The Manila Galleons: Treasures For The ”Queen Of The Orient”“: “Nowhere in the annals of the Spanish Empire’s colonial history did a treasure fleet attract so much intrigue and notoriety for its precious cargoes bound for the Far East. Maritime historians continue to pay homage to these vessels and their influence on international commerce. These were the largest ships afloat, plying long and risky routes. On an average, three to five million silver pesos were shipped annually from Mexican mints to Manila, the “Queen of the Orient.” The silver and gold was waggishly referred to as “silk money.” Silk stockings were prized by the fashionable Spanish gentry in Mexico and Spain. But the silver and gold bought other lavish exports as well. They came from all over the Far East: spices, Ming porcelain, opals, amethysts, pearls and jade. There were art treasures, ebony furniture, carved ivory and other exquisite rarities found only in China, Japan, India, Burma and Siam. [Source: Ellsworth Boyd, “The Manila Galleons: Treasures For The ”Queen Of The Orient”“, July 2, 2012]

RELATED ARTICLES:

TRADE AND PLANTATIONS IN THE PHILIPPINES UNDER THE SPANISH factsanddetails.com

SPANISH ARRIVE IN THE PHILIPPINES: EXPEDITIONS, LEGAZPI, TAKING CONTROL factsanddetails.com

CHRISTIANIZATION OF THE PHILIPPINES: MISSIONARIES, SUCCESS, FRIAROCRACY factsanddetails.com

PHILIPPINES UNDER SPANISH RULE: LIFE, COLONIZATION, CHINESE factsanddetails.com

PHILIPPINES BEFORE THE ARRIVAL OF THE SPANISH factsanddetails.com

PRE-COLONIAL FILIPINO STATES factsanddetails.com

MAGELLAN IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com

Manila Galleon Ships and Crew

The Manila galleons were owned and sailed by the Spanish crown. Most were built from strong tropical hardwoods in the port of Cavite in Manila Bay using Spanish designs with oriental features. Over time the ships grew in size to accommodate the increase in trade. Early ships carried around 300 tons. By the late 1600s they were carrying more than a thousand tons. The giant “Santisima Trinidad”, captured by the English in 1792, carried 2,000 tons. [Source: Eugene Lyon, National Geographic, September 1990 ]

Large galleon usually weighed 1,700 to 2,000 tons, were 140 to 160 feet long and could carry a thousand passengers. A typical galleon carried 300 people. Passengers included Chinese traders, Spanish priests, nuns, merchants, Filipino laborers and condemned prisoners. The crew was comprised of mostly Spanish officers, petty officers, gunners, seamen, apprentices and pages. The sails on the Manila galleons were made in Ilcos on Luzon. Anchor lines and rigging were woven from Manila hemp. Fastenings were forged by the Spanish. Chinese and Japanese smiths used iron imported from China and Japan.

Hundreds of storage jars with fresh water were secured below the deck and hung overhead, lashed with Manila hemp. Other stores included salted meats, biscuits, wine, honey, garbanzo beans, chickens, hogs, garlic and olive oil. Bundles were compressed and packed, usually by Chinese, and packed in such a way as reduce space. Cannons were stored in the hold to make more room on the decks for merchandise, but this left the ships vulnerable to attacks.

Ellsworth Boyd wrote in “The Manila Galleons: Treasures For The ”Queen Of The Orient”“: “Picture if you will, a four-deck, 100-gun, 2,500-ton vessel crossing the Pacific loaded with treasure and not making landfall for six months. Picture it as short and broad—with high fore and stern castles—carrying so much silver and gold, it draws 40 feet of water while skirting coral reefs 30 feet deep. It’s no wonder that dozens of them sank from 1570 to 1815, leaving a trail of treasure across the globe. [Source: Ellsworth Boyd, “The Manila Galleons: Treasures For The ”Queen Of The Orient”“, July 2, 2012]

Goods Carried on the Manila Galleons

Ships from the Philippines to Mexico carried silk, woven rugs, jade, toys, furniture, chinaware and porcelain from China; cinnamon, cloves, pepper, nutmeg and other spices from the Spice Island; cotton goods, ivory, diamonds, topazes, other gemstones, fine textiles, woodcarvings and curry form India; ivory from Cambodia; camphor, ceramic ware and gemstones from Borneo; and ebony, ivory, civet musk, rubies, sapphires and jewelry set with precious gems from Burma, Sri Lanka and Thailand and elsewhere in the Far East. [Source: Eugene Lyon, National Geographic, September 1990 ]

Japanese ships arrived in Manila with amber, knives. samurai swords, cabinetwork, saltpeter to make gunpowder, bronze and copper. Some goods came from the Philippines, namely gold, copra, coconut shell products, cotton cloth from Ilocos on Luzon, cotton stockings and petticoats, gauze made in Cebu, and rope, burlap and hammocks made of hemp, and jewelry made by Chinese and Filipino artisans in Manila.

The most highly sought after good from China was silk. Mercury from China was essential for refining silver ore. Bezoar stones from Asia, taken from the stomachs of ruminant animals were also valued because it was believed the could indicate the presence fo poison in wine. The Chinese shipped porcelain in such large volumes they began designing products specifically for the European market.

Ships from Acapulco to Manila carried mostly silver and manufactured goods from Europe. Chinese and Asians became dependent on New World silver to conduct trade and accumulate wealth. Dependence on the metal became so strong it seemed that supply could never keep up with demand. The Chinese recast Mexican bullion into shoe-shaped ingots, called “sycees”, and incised Spanish coins with a chop mark that redefined their value in terms of tales, the Chinese currency.

Shipping records reveal that roughly one-third of all the silver and gold extracted from Spain’s American colonies eventually traveled to the Far East aboard the slow but heavily laden Manila galleons. Much of this treasure came from rich mining centers such as Potosí in present-day Bolivia. Bars of bullion and massive chests filled with coins were carefully stowed deep in the main hold, positioned over the keel to serve not only as cargo but also as ballast, ensuring the ship’s stability. In addition to precious metals, the vessels transported essential supplies for Spanish settlers in the Mariana Islands and the Philippines. [Source: Ellsworth Boyd, “The Manila Galleons: Treasures For The ”Queen Of The Orient”“, July 2, 2012]

Manila functioned as a major entrepôt, receiving goods from India and various parts of Southeast Asia. Trade was also conducted with Japan until 1638, when the Japan adopted a policy of seclusion from most Western nations, though limited commerce continued through the Dutch. Demand in Europe and the Americas for Asian silks, spices, porcelains, and other luxury goods grew insatiable, and the immense profits justified the dangers of the long Pacific crossing. Treasure fleets regularly carried silver from the New World to Acapulco, but some ships were lost along the western coasts of South and Central America, their valuable cargoes claimed by storms or shipwreck. [Source: Steve Singer, Manila Galleons]

Route of the Manila Galleons to Mexico

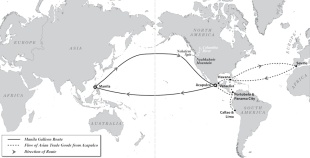

On average a single Spanish galleon sailed eastward from Manila between April and July with treasures from the Orient and returned with from Acapulco with silver from Mexico, Peru and Bolivia between October and January. The journey each way was around 15,000 kilometers (about 9,000 miles), the world’s longest navigation route. Although one route went north of the Hawaiian island and the other went south of them, the islands were never discovered. [Source: Eugene Lyon, National Geographic, September 1990 ]

The galleons heading to the Philippines traveled more or less in a straight line equidistance between the Equator and the Tropic of Cancer and followed the North Equatorial Current and Northeast Trade Winds south of Hawaii. The journey was generally a piece of cake. The winds were steady and the seas were placid. Often the ship made it less than three months. The main object was to get to the Marianas (islands east of the Philippines) before the contrary winds of the autumn monsoon kicked up.

The galleon heading to Mexico followed the Kuroshio current to the same latitudes of Japan and then the took the North-Pacific Current and westerly winds eastward past Guam and the Marianas and north of Hawaii to California and then followed the coast down to Mexico. The route was discovered by one of Legazpi’s ships, the San Lucus, which sailed north as far as Japan and south as far as New Guinea before discovering a reliable west-to-east wind through trial and error.

The journey eastward was much more hazardous. It often took serval weeks just to get out of the dangerous waters of the Philippines and the whole journey could take almost a year. A traveler in 1697 wrote: “The voyage from the Philippine islands to America may be called the longest and most dreadful of any in the world, as well because of the vast ocean to be crossed, being almost one half the terraqueous globe, with the wind always a-head; as for the terrible tempest that happen there, one upon the back of another.”

Finding the Eastward Route to Mexico

The Manila–Acapulco Galleon Trade began in 1565 when Andrés de Urdaneta, serving as pilot for Miguel López de Legazpi, discovered a viable return route from Cebu to Mexico. Urdaneta theorized that Pacific wind patterns moved in a circular system. By sailing far north before turning east, ships could catch the prevailing westerlies that would carry them across the ocean to North America. His theory proved correct when his vessel reached the coast near Cape Mendocino in California, after which it followed the shoreline southward to Acapulco. [Source: Oliver M. Mendoza, iloilocityboy.blogspot.jp. June 5, 2006]

Although Spanish expeditions had reached the Philippines from Mexico before 1564, they had failed to locate a reliable eastward return passage. In 1564, a fleet of four ships led by Legazpi finally set out to establish a permanent presence and secure a route back. The expedition was authorized by Luis de Velasco under the authority of Philip II of Spain. The fleet departed Mexico on November 21, 1564, embarking on a 9,000-nautical-mile voyage. They sighted Samar on February 13, 1565, and anchored at Cebu on April 27.

In their search for a return route, the fleet divided. Some ships sailed south toward New Guinea, while Urdaneta insisted the solution lay to the north. The small 40-ton San Lucas ventured toward waters near Japan, where it encountered favorable westerly winds and currents that carried it across the Pacific to the California coast near Cape Mendocino. From there, it sailed south to Acapulco, arriving in October 1565. [Source: Steve Singer, Manila Galleons]

Accounts differ regarding which ship first completed the return voyage. Some sources credit the San Pablo, another vessel in the fleet, with discovering the route soon after the San Lucas. Other accounts suggest that one ship—possibly the San Lucas—had separated from the fleet and reached Acapulco as early as July 1565. Meanwhile, Urdaneta himself reportedly sailed as far north as 38 degrees latitude off Japan before heading east. His crew endured severe hardship, and many died before the ship finally reached Acapulco.

This successful navigation established the transpacific trade route known as the Manila galleon trade, or “nao de la China” (“ship of China”). The route would link Asia and the Americas for more than two centuries. Ironically, Legazpi’s own vessel, the San Pablo of 300 tons, became the first Manila galleon to be wrecked in 1568 while en route back to Mexico.

Manila Galleon Business

Almost every Spaniard and every enterprises and institution in the Philippines had its hand in the Manila galleon trade somehow. Even the church was involved. Priests, bishops and even archbishops controlled consignments. At first space on board the ship was divided according to a system of permits that were supposed to be in fair manner but quickly the system became poisoned by corruption and favoritism. [Source: Eugene Lyon, National Geographic, September 1990 ]

If the ships got through and the goods found their way to their destination and the money or bartered goods found their way back, merchants often made profits between 100 and 300 percent. If something happened to the galleon and goods and money did not make it to their destinations the Philippines suffered through a year of hardship.

Although taxes were collected on the galleon trade, they were never sufficient to cover the cost of administering the colony. A yearly subsidy called the situado was sent from Spain or Mexico. In the nineteenth century, the export of Manila hemp (used for ship rigging), sugar, and tobacco spurred the colony's economic development, helping to create an emerging middle class.[Source: Nicholas P. Cushner, Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, Gale, 2008]

Sometimes a large portion of the cargo was contraband. Even though there were heavy penalties for carrying contraband (confiscation of the goods and four years chained to the oar of a galley for the offender) the rules were flagrantly violated. Bullion was routinely carried in hollowed-out timbers, cottons bails and even the rinds of cheeses. To avoid taxes and other restrictions, merchants undervalued their goods on records and documents. Regulation and enforcement of the weight limits were lax and corruption was high. With the welfare of the entire Philippines colony and thousands of people dependent on a single shipment a year, there was a temptation to overload the vessel which made it vulnerable to sinking and attacks.

The Spaniards went through great lengths to make sure the trans-Pacific routes were only theirs. In 1600, when a Dutch fleet rounded South America and sailed across the Pacific Ocean to the Philippines, Spaniards captured them, executed 25 of them with a garrote, and sent the captain back to the Netherlands with a message to the Dutch not come back. Many of the so-called “Spaniards” in the Philippines were actually of Mexican descent. This is so because sea travel from Spain to the Philippines was very difficult before the advent of steam navigation and the opening of the Suez Canal.

Hardships on Board the Manila Galleon

Disease and poor nutrition took their toll on the passengers and crew of the Manila galleons, especially if a voyage was considerably longer than expected. The journey from the Philippines to Mexico was particularly hazardous. Often water supplies would become contaminated or run out and the galleon had to depend on rainwater (Mats were set out to funnel water into jars). [Source: Eugene Lyon, National Geographic, September 1990 ]

People were packed together like sardines and suffered under the stress of unbearable monotony. To pass the time, some people just say around like zombies. Other played endless games of cards and wagered on times of events. Many were ravaged by disease.

A 17th century Italian on the journey from Manila to Acapulco wrote: “there is hunger, thirst, sickness, cold, continual watching, and other sufferings...Abundance of flies fall into the dishes of broth, in which there also swim worms of several sorts...On fish days the common diet was old rank fish boil’d in fair water and salt; at noon we had “mongos”, something like kidney beans, in which here were so many maggots, that they swam at the top of the broth, and the quantity was so great, that besides the loathing they caus’d, I doubted whether the dinner was fish or flesh.”

Passengers and crew alike suffered from dysentery and beri-beri (severe Vitamin B1 deficiency). Particularly nasty was scurvy caused by a lack of Vitamin C. Known as the “Dutch disease,” it caused victims’s arms, legs and trunks to become covered with bruises and livid spots and caused the gums to swell up and bleed and teeth to fall out. Oranges and lemons were carried as a preventative measure against scurvy. Some of the first citrus groves planted by the Spaniards were to supply fruit for the galleon trade.

Problems Faced by the Trans-Pacific Manila Galleons

The 15,000-kilometer voyage of the Manila galleons was plagued by pirates, storms and slack winds. In 1578 Drake’s fleet captured a merchant ships loaded with Oriental goods. In 1743, the overloaded and underarmed silver galleon “Covadonga” was attacked and easily taken by the British, who took possession of more than a million silver pesos, gold bullion and a host of valuable goods. The “Covadonga” took 159 shots and lost 70 men. the British lost only two. When the treasure was brought aback to Britain it took 32 wagons to transport it. In some cases pirates simply hung out near the ports where the ships departed from and attacked them after they left. [Source: Eugene Lyon, National Geographic, September 1990 ]

Many galleons never even made it out the Philippines, whose waters were made dangerous by typhoons, shoals and sunken rocks. San Bernardino Strait, also known as the Embocadero, or outlet, was narrow and full of obstacles and particularly fear by navigators. Ellsworth Boyd wrote in “The Manila Galleons: Treasures For The ”Queen Of The Orient”“: “ The Strait of San Bernardino, on the eastern end of Luzon in the Philippine Archipelago, separates the Pacific from the China Sea and remains one of the most treacherous passages ships must ply. Even the most seasoned mariners fear entering and exiting the shallow poorly marked waterway. Of the approximately 130 Manila Galleons lost, close to 100 sank within a 50-mile radius of the entrance to this dangerous strait. Some of the vessels simply ran aground on reefs or shoals, while others were lost in storms or sunk by British and Dutch privateers. [Sources: Ellsworth Boyd, “The Manila Galleons: Treasures For The ”Queen Of The Orient”“, July 2, 2012]

More obstacles lay in the open ocean, namely storms, that could arise without waning and toss a ship like “a pair of socks in the spin cycle of a washing machine.” For the eastbound ships the first land fall was often at Cape Mendocino in northern California, near San Francisco—a welcome sight indeed. In some cases dozens died before the ship reached California. One 17th century galleon lost 92 in people in 15 days and 206 of its of original crew. But that wasn’t the worst case. The “San Jose” lost everyone aboard to starvation and disease. The ship was found floating with only cargo and corpses on board.

Westward Trade of the Manila Galleons

On the trip from Mexico, the galleon carried silver, which paid for the next shipment of luxury items. It is estimated that as much as one-third of the silver mined in New Spain and Peru went to the Far East. Because of the silver, the Philippines-bound Manila galleon was a sought-after prize for pirates and enemies of Spain. However, only one galleon was captured at sea: the Covadonga, by George Anson in 1743. Anson found 1,313,843 pieces of eight aboard. At Canton, a thorough search of the galleon revealed more silver hidden in cheese rinds, the ship's timbers, and other places—clear evidence of smuggling. [Source: Nicholas P. Cushner, Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, Gale, 2008]

Departing from Acapulco each January, the Manila galleons crossed the usually calm Pacific, riding favorable trade winds toward the Mariana Islands before continuing on to the Philippines. The voyage typically lasted about three months, although storms and navigational hazards occasionally caused shipwrecks. Until 1593, three or more vessels sailed annually from both Manila and Acapulco. [Source: Steve Singer, Manila Galleons]

As the trade grew increasingly profitable, Spanish merchants in Spain protested the loss of potential revenue. In response, the Crown issued regulations in 1593 limiting the trade to two ships per year—one sailing from each port—with an additional vessel held in reserve at both Acapulco and Manila. The law also restricted the tonnage and cargo capacity of the ships. In practice, however, these limits were widely ignored and seldom enforced. The Manila galleons were among the largest ships constructed by Spain. During the sixteenth century, they commonly ranged from 1,700 to 2,000 tons, and between 700 and more than 1,000 passengers might crowd aboard for the return voyage to Mexico.

Despite the regulation calling for two ships annually after 1593, many years saw only a single galleon complete the return journey to Acapulco. The eastbound crossing became notorious as one of the longest and most perilous sea voyages in the world. Although it could take as little as four months under ideal conditions, the trip more often lasted seven months or longer. Disease, starvation, and malnutrition frequently claimed large numbers of lives—sometimes more than half of those on board.

One tragic example was the Manila galleon San José, discovered drifting off the Mexican coast in the mid-seventeenth century, more than a year after departing Manila. Not a single survivor remained; all had perished from disease or hunger. Another case was the Santa Margarita, which left Manila in 1600 and struggled against storms for eight months before wrecking on Carpana Island in the Marianas, leaving only a handful of survivors.

Eastward Trade of the Manila Galleons

Goods were shipped from ports in India, Southeast Asia, and China to Manila, where they were processed and stored by the Chinese community. Then, a handful of Spanish merchants, each allotted a specific amount of space on the galleon each year, transshipped the goods. [Source: Nicholas P. Cushner, Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, Gale, 2008]

After departing from Cavite on Manila Bay—usually in July—a Manila galleon first had to navigate the maze of islands and reefs north of the Philippines. Reaching the northern Marianas could take weeks, and many ships were wrecked on these hazardous shoals. From there, the galleons steered toward higher latitudes near Japan, seeking the westerly winds and currents that would carry them east across the Pacific. For three or four months—or even longer—no land was sighted, and the harsh conditions often made life onboard unbearable. Eventually, the ships would glimpse Cape Mendocino along the northern California coast, then follow the shoreline southward to Acapulco. Even along this final stretch, a number of Manila galleons were lost to storms and hidden coastal dangers. [Source: Steve Singer, Manila Galleons]

Once in Acapulco, Asian goods were sold to merchants from across the Americas. Much of the cargo was transported overland to Veracruz, where it was loaded onto ships of the Spanish treasure fleets bound for Havana and ultimately Spain. Many of these vessels also met disaster at sea. The famous 1715 Treasure Fleet and 1733 Treasure Fleet wrecks off Florida yielded artifacts from the Far East, including porcelain and jewelry. Any Spanish shipwreck in the Western Hemisphere carrying Asian cargo must have sunk after 1565, though Chinese goods did not begin arriving regularly in Acapulco until 1573.

Porcelain from the Ming dynasty and Qing dynasty, transported aboard Spanish ships from the Philippines to the Americas, has proven invaluable in dating shipwrecks. These ceramics are well studied and can be accurately identified by period. Most Manila galleons were eventually constructed in the Philippines, particularly at the Cavite shipyards and at other local yards such as Palantiau. Although based on European designs, they were sturdier, built from abundant hardwoods like teak and mahogany. Their planking often used dense lanang wood, reputedly strong enough to resist cannon fire—another feature that can help identify a Manila galleon wreck. Manila hemp also gained fame as one of the finest materials for ship rigging and became an important export commodity.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, much of the porcelain and carved ivory shipped across the Pacific remained in the Americas and influenced local artistic traditions. Mexican ceramics vividly reflect the impact of the galleon trade, while Chinese silk patterns may have inspired decorative motifs in Guatemalan sculpture. Even the facial features of certain colonial-era statues suggest subtle influence from Asian ivory carvings, demonstrating the far-reaching cultural effects of the Manila galleon trade. [Source: Johanna Hecht, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Ar Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Manila Galleon Shipwrecks

More than 40 galleons did not make it. Most perished in bad weather and rough seas. More than 25 galleons wrecked off the Philippines. Others were lost around the Marianas. Often they were westbound silver galleons. In one three year period (1655-57) four galleons were lost. Five Manila Galleons are known to have sunk off the west coast of the United States. One, the San Agustin, sank in 1595, victim of a gale in Drakes Bay, northwest of San Francisco.

The “Pilar de Saragoza y Santiago” sunk after it struck Cocos reef off the southern coast of Guam on June 2, 1690. The ship sunk so quickly that only 5,000 pesos worth of silver coins was salvaged. The rest, an estimated 1 million to 2 million silver pesos, was lost. The crew of 120 and 43 soldiers and 22 missionaries on board were all saved. The estimated value of the cargo on the ship if found today is $1 billion. Thus far finding the shipwreck has been elusive. In May 1989 Philip Masters of the University of Florida found documents about the sinking in the archives at Seville. The documents, which Masters said had probably been looked at, described the location of the “Pilar de Saragoza y Santiago” shipwreck.

The wrecks of the Manila galleons rank among the richest maritime sites in the world, though only a handful have been conclusively identified. One of the most notable is the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, which was sailing from Manila to Acapulco when it wrecked off the southwest tip of Saipan on September 20, 1638. At roughly 2,000 tons, she was the largest Spanish vessel built up to that time. Another is the Nuestra Señora del Pilar, which went down in 1690 near the southwest coast of Guam; the site has been located and explored by divers in recent years. [Source: Steve Singer, Manila Galleons]

The San Agustín, part of a four-ship fleet bound from Manila to Acapulco, wrecked in 1690 in Drake’s Bay north of San Francisco. The site, reportedly identified by maritime archaeologist Robert Marx, lies within what is now the Point Reyes National Seashore, where legal protections have limited excavation. Meanwhile, the San Diego, discovered in Manila Bay in 1991, has yielded more than 28,000 recovered artifacts. Other possible galleon wrecks have reportedly been found in Philippine waters by local fishermen and divers, though not all are under formal archaeological investigation.

Several Manila galleons are believed to lie undiscovered off the coasts of California and Mexico. The Santa Marta ran aground on Santa Catalina Island in 1528, with part of her cargo salvaged. The Nuestra Señora de Ayuda, a 320-ton vessel, struck a rock west of Catalina Island in 1641; some crew survived, but the cargo was lost. The San Sebastián, attacked by English privateer George Compton on January 7, 1754, was deliberately run aground west of Santa Catalina Island before sinking in deep water. Artifacts recovered along the Oregon and California coasts may also be linked to lost galleons.

One of the most tragic losses was the Santa María de los Valles. Departing Manila in 1668 with 778 people and a cargo valued at over three million pesos, she finally reached Acapulco after a grueling voyage. Just two days before Christmas, and only hours after anchoring, the ship caught fire and sank within an hour, taking more than 330 lives and her entire treasure to the bottom.

In fact, most Manila galleons were lost in Asian waters, particularly around the Philippines, China, and Japan. The San Martín (a patache) wrecked near Canton in 1578 carrying large quantities of silver, and two additional vessels were lost in the same region in 1598. The San Francisco sank off eastern Kyushu in 1608 with substantial gold and silver aboard. The Santísima Trinidad, carrying cargo worth over three million pesos, was destroyed by a typhoon in 1616 at Cape Satano in southern Japan.

Other vessels met similar fates in Philippine waters. The Jesús María and the Santa Ana were ambushed by a superior Dutch fleet in 1620 and sank in the San Bernardino Strait with more than two million silver pesos. In 1639, the San Ambrosio and another ship from Acapulco were lost in a typhoon off Cagayan, also carrying millions in silver. The Santo Cristo de Burgos ran aground near Ticao Island in 1726; although the crew survived, fire destroyed the vessel and its cargo. The San Andrés wrecked near Ticao in 1797, losing part of its valuable freight. Finally, the Santa María Magdalena, dangerously overloaded when she departed Cavite in 1734, capsized and sank within sight of her anchorage—another costly reminder of the hazards of the Manila galleon trade.

Nuestra de la Concepcion

On September 20, 1638, the “Nuestra de la Concepcion”, an Acapulco-bound Spanish galleon loaded with a cargo of oriental treasures sunk off the southern coast of Saipan after being pushed by a storm onto a reef. Most of the 400 people on board perished and her treasure was spilled in to the sea. The site is now overlooked by a golf course, and Ming dynasty porcelain shards are scattered along the coastline, which helped to pinpoint the wreck. [Source: Bill Mather, National Geographic, September 1990]

The “Nuestra de la Concepcion” was the largest European ship built up to her time. She was between 140 and 160 feet long and displaced 2,000 tons. The ship carried a cargo worth tens of millions of dollars. The wreck was blamed on an inexperienced commander—a nephew of the Manila governor—who mismanaged the ship, causing his officers to mutiny, and allowed the ship to pass into reef-strewn waters in bad weather. High winds snapped the mast and the overloaded ship was carried by currents and winds and driven it into the reef. People leapt into the sea. Many of those who made it to shore were killed with spears and slingstones by local Chamorro islanders. Six Spaniards escaped and made it to Guam and reached the Philippines in an open boat ten months later.

The “Nuestra de la Concepcion” was salvaged over a two year period in the late 1980s by a team led by William Mathers of the Pacific Sea Recovery Group. After combing a half square mile area off the southwestern coast of Saipan the salvagers found 1,500 pieces of gold jewelry, 156 storage jars and few hundred cannonballs. Many of the items had become embedded in coral after drifting eastward from the original wreck site. Perhaps the greatest treasure was solid gold plate and ewer set thought have been intended as a gift from the King of Spain to the Emperor of Japan. A solid gold cross imbedded with diamonds was also found. Other items had been salvaged soon after the wreck by Spaniards and over time by local islanders.

Sunken Galleon Discovered Off the Capiz Coast of the Philippines

In May 2006, a scuba diver from Capiz discovered what appeared to be an ancient shipwreck off Sitio Tabai in Barangay Barra, Roxas City. Ronilo Lorenzo, an experienced local diver, came upon the vessel by chance while searching for seahorses. Upon learning of the find, Mayor Tony del Rosario ordered the site secured and initiated steps toward salvaging the wreck. He expressed excitement over the possibility that the ship might be a Spanish galleon and proposed displaying it at the Roxas City Museum for public viewing. [Source: Oliver M. Mendoza, iloilocityboy.blogspot.jp. June 5, 2006 ]

It was the first reported discovery of a possible Spanish galleon in Western Visayas. Although early news accounts were unclear and details remained limited, the find quickly drew the attention of historians and enthusiasts of Spanish-era maritime history. If experts were to confirm that the vessel was indeed a galleon, the discovery would raise intriguing questions. Capiz does not lie along the usual route taken by ships sailing from Manila to Acapulco, so its presence there would require explanation.

Traditionally, Manila galleons departed from Manila and often made a brief stop at Taytay in Palawan before heading into the open Pacific. Taytay, a quiet town in northern Palawan, is home to a well-preserved Spanish fort, and local lore maintains that galleon crews once obtained final provisions there before embarking on the long, four-month voyage to Mexico. Fishermen in the area occasionally report finding old coins and artifacts near the historic fort.

The so-called “Capiz galleon,” therefore, presents a puzzle. One possibility is that the ship was blown off course by a typhoon, a frequent occurrence in Philippine waters. Another is that the wreck may not be a Spanish galleon at all, but rather a Chinese junk or an inter-island trading vessel. Chinese merchants had longstanding trade relations with the people of Panay long before Spanish colonization, and historical records note that local ships regularly sailed the waters off Capiz. Whatever the outcome of further investigation, the discovery has generated renewed interest in regional history and promises to deepen understanding of the area’s maritime past.

End of the Manila Galleon Trade

The Manila galleon trade was hurt by: 1) corruption, smuggling and competition; 2) disputes over shares and profits; and 3) problems back in Spain. Over time the power and wealth of the British, French and Dutch grew and challenged Spain and exploited the Asian trade in their own way. Spain’s monopoly began t unravel in the late 1700s and early 1800s under restrictive Spanish trade practices, disruptions caused by the Napoleonic wars and the independence movement in Mexico and Latin America. The legacy of the Manila galleons lives on. In Acapulco, dancer still wear “China poblana” dresses. In Cavite, Filipinos honors the patron of the galleons to Mexico, Our Lady of Porta Vaga, with a feast and the transportation of a shrine with an icon across Manila Bay.

The “Magallanes”, the last Manila galleon, left Manila in 1811, and returned four years later. The end of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade was sealed when Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821. As long as the Spanish empire on the eastern rim of the Pacific remained intact and the galleons sailed to and from Acapulco, there was little incentive on the part of colonial authorities to promote the development of the Philippines, despite the initiatives of José Basco y Vargas during his career as governor in Manila. After his departure, the Economic Society was allowed to fall on hard times, and the Royal Company showed decreasing profits. The independence of Spain's Latin American colonies, particularly Mexico in 1821, forced a fundamental reorientation of policy. Cut off from the Mexican subsidies and protected Latin American markets, the islands had to pay for themselves. As a result, in the late eighteenth century commercial isolation became less feasible. [Source: Library of Congress, *]

Growing numbers of foreign merchants in Manila spurred the integration of the Philippines into an international commercial system linking industrialized Europe and North America with sources of raw materials and markets in the Americas and Asia. In principle, non-Spanish Europeans were not allowed to reside in Manila or elsewhere in the islands, but in fact British, American, French, and other foreign merchants circumvented this prohibition by flying the flags of Asian states or conniving with local officials. In 1834 the crown abolished the Royal Company of the Philippines and formally recognized free trade, opening the port of Manila to unrestricted foreign commerce. *

By 1856 there were thirteen foreign trading firms in Manila, of which seven were British and two American; between 1855 and 1873 the Spanish opened new ports to foreign trade, including Iloilo on Panay, Zamboanga in the western portion of Mindanao, Cebu on Cebu, and Legaspi in the Bicol area of southern Luzon. The growing prominence of steam over sail navigation and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 contributed to spectacular increases in the volume of trade. In 1851 exports and imports totaled some US$8.2 million; ten years later, they had risen to US$18.9 million and by 1870 were US$53.3 million. Exports alone grew by US$20 million between 1861 and 1870. British and United States merchants dominated Philippine commerce, the former in an especially favored position because of their bases in Singapore, Hong Kong, and the island of Borneo. *

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Library of Congress, Philippines Department of Tourism, Philippines government websites, Encyclopedia.com, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Wikipedia, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, UNESCO, National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) the official government agency for culture in the Philippines), Lonely Planet Guides, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, The Conversation, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Google AI, and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026