PRE-SPANISH PHILIPPINES

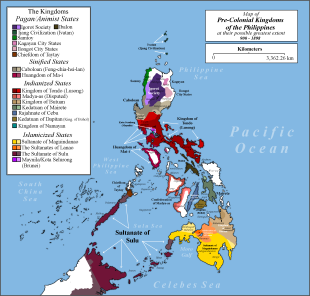

Pre-colonial Philippines was not a single, unified country but rather a collection of organized and culturally rich communities with sophisticated social and economic systems. Before 1521, these societies interacted actively with neighboring Asian civilizations through trade, diplomacy, and migration. Instead of one centralized state, the archipelago was composed of numerous independent polities that developed their own leadership structures, customs, and identities.

Pre-colonial Philippine society was centered on maritime communities known as barangays, which ranged from small villages of 30 to 100 households to larger and more complex political entities. Each barangay was ruled by a datu, a chief who exercised authority over governance, justice, and warfare. In some regions, these settlements evolved into larger states such as the Rajahnate of Cebu and the Sulu Sultanate. While most communities practiced animism, elements of Hindu-Buddhist traditions were also present due to regional trade connections, and later Islamic influences became prominent in the south.

The political structure of these communities emphasized local autonomy. Barangays functioned independently, though alliances and confederations sometimes formed for trade or defense. Social structure was highly stratified. At the top were the nobles, often referred to as the maginoo, followed by freemen or warrior classes such as the maharlika. Below them were dependents known as alipin, whose obligations to their patrons varied in degree and were not identical to chattel slavery. Leadership roles extended beyond the datu; spiritual authority was held by the babaylan, typically a priestess who conducted rituals and mediated between the human and spirit worlds.

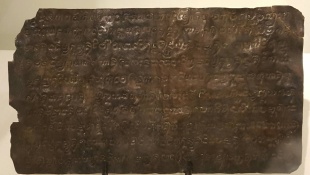

The economy of pre-colonial Philippines was diverse and regionally specialized. Agriculture formed the backbone of subsistence, particularly rice cultivation, along with coconuts and root crops. Fishing and seafaring were essential, reflecting the archipelago’s geography. Gold mining and metalwork were well developed, and trade flourished with China, India, and other parts of Southeast Asia. Archaeological and documentary evidence, including the Laguna Copperplate Inscription dated to 900 AD, demonstrates the existence of literate, organized, and law-abiding societies engaged in regional networks.

Cultural practices reflected both indigenous beliefs and foreign influences. Writing was conducted using Baybayin, a syllabic script used for communication and documentation. Religion was primarily animistic, centered on reverence for nature spirits and ancestral beings known as anitos. Tattooing was widespread and signified beauty, bravery, and social status, especially among warriors. Martial traditions were strong; communities engaged in defense and raiding expeditions known as mangayao. They built swift warships called caracoa and used indigenous weapons, including lantaka swivel guns, demonstrating considerable maritime military skill.

Significant historical developments shaped this era. In the 14th century, Islam was introduced to the southern Philippines, leading to the establishment of Islamic sultanates. The pre-colonial period formally ended in 1521 with the arrival of Ferdinand Magellan, which marked the beginning of sustained Spanish contact and eventual colonization. Despite later foreign rule, the foundations of political organization, trade, belief systems, and social hierarchy in pre-colonial Philippines reveal a complex and dynamic civilization long before European arrival.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FIRST HOMININS IN THE PHILIPPINES: 709,000-YEAR-OLD TOOLS, HOMO LUZONENSIS TABON MAN factsanddetails.com

AUSTRONESIAN PEOPLE OF THE PACIFIC, INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, TAIWAN AND THE PHILIPPINES: ORIGIN, HISTORY, EXPANSION factsanddetails.com

MALAYS AND MALAY-RELATED PEOPLE: HISTORY, DEFINITIONS, ORIGINS, LIFE, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

EARLY HISTORY OF THE PHILIPPINES: MIGRATIONS, DISPLACEMENTS, DNA, factsanddetails.com

PHILIPPINES BEFORE THE ARRIVAL OF THE SPANISH factsanddetails.com

PHILIPPINES HISTORY: NAMES, THEMES, TIMELINE, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

Pre-Colonial Filipino States and Polities

Cainta was a fortified upriver polity located in what is now Rizal province. It occupied both banks of a branch of the Pasig River, which divided the settlement at its center. A moat encircled its log palisades and stone defenses, which were equipped with native cannons known as lantakas. The entire settlement was further protected by dense bamboo thickets. Namayan, another polity along the Pasig River, developed as a confederation of neighboring barangays. According to local tradition, it reached its height between the 11th and 14th centuries. Archaeological discoveries in Santa Ana have revealed the oldest evidence of continuous habitation among the Pasig River settlements, predating artifacts uncovered in the historical sites of Maynila and Tondo. [Source: Wikipedia]

Kumintang was a prominent polity situated along the Calumpang River in present-day Batangas. Local tradition identifies its ruler as the legendary Gat Pulintan, who reportedly resisted Spanish conversion efforts and withdrew to the hills to continue opposing Spanish rule. In 1581, Kumintang was incorporated as a Spanish town and was later unofficially renamed Batangan.

Sandao, also called Sanyu, was a precolonial Filipino polity mentioned in Chinese records. It reportedly included the islands of Jiamayan (modern Calamian), Balaoyou (Palawan), and Pulihuan (near present-day Manila). The 1225 Chinese gazetteer Zhufan zhi described Sandao as a vassal state of the more powerful Ma-i, which was centered in Mindoro. Pulilu was another precolonial polity, located at present-day Polillo, Quezon, and also mentioned in the Zhufan zhi. It was politically linked to Sandao and, like it, ultimately subordinate to Ma-i. Chinese accounts describe Pulilu’s inhabitants as warlike and inclined toward raiding. The surrounding seas were noted for dangerous coral reefs and for producing rare red and blue corals, which were the polity’s main export.

Sanmalan was a precolonial Philippine polity centered in what is now Zamboanga, possibly around present-day Zamboanga City within the ancestral lands of the Subanon people. Chinese annals recorded it as “Sanmalan” and state that in A.D. 1011 its ruler, Rajah Chulan, sent an envoy named Ali Bakti to the Chinese imperial court. The tribute he presented—aromatics, dates, glassware, ivory, peaches, refined sugar, and rose water—indicates that Sanmalan maintained trade connections reaching as far as Western Asia. However, by 1225, the Chinese chronicle Zhufan Zhi referred to the polity as Shahuagong and described a shift in character from a trading center to a pirate state engaged in slave raiding. As recorded: “Many of the people of the country of Shahuagong go out into the open sea on pirate raids. When they take captives, they bind them and sell them to Shepo (Java) (as slaves)”

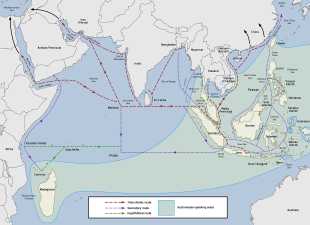

Majapahit Empire and Shrivijaya Kingdom

Parts of present-day Philippines were under the control of the Java-based Hindu Majapahit empire. The Majapahit Kingdom (1293-1520) was perhaps the greatest of the early Indonesian kingdoms. It was founded in 1294 in East Java by Wijaya, who defeated the invading Mongols. Majapahit flourished at the end of what is known as Indonesia's "classical age". This was a period in which the religions of Hinduism and Buddhism were predominant cultural influences. Beginning with the first appearance of Indianised kingdoms in the Malay Archipelago in the A.D. 5th century, this classical age was to last for more than a millennium, until the final collapse of Majapahit in the late 15th century and the establishing of Java's first Islamic sultanate at Demak. [Source: ancientworlds.net]

In the 7th century the powerful Shrivijaya kingdom was established in Sumatra and eventually reached or at least exerted influence on what is now the Philippines and introduced a mixture of Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism. Shrivijaya was a maritime empire based in Sumatra that lasted for 500 years from the 8th century to the 13th century. It ruled a string of principalities in what is today Southern Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. When Srivijaya in Chaiya extended its sphere of influence, those cities became tributary states of Srivijaya.

The site of Srivijaya's centre is thought be at a river mouth in eastern Sumatra, based near what is now Palembang. For over six centuries the Maharajahs of Srivijaya ruled a maritime empire that became the main power in the archipelago. The empire was based around trade, with local kings (dhatus or community leaders) swearing allegiance to the central lord for mutual profit. [Source: Wikipedia]

From the 12th century onward, Srivijaya declined as its authority over vassal states fractured, conflicts with Javanese and Indian powers intensified, and its political center shifted to Melayu in Sumatra. The spread of Islam further weakened Srivijaya, while external powers—including the Siamese kingdom of Sukhothai and the Javanese Majapahit Empire—came to dominate much of the Malay Peninsula by the 13th and 14th centuries. By then, Srivijaya had lost Chinese support and control of key trade routes. In contrast, Borneo developed largely independently, with Brunei emerging as its principal power until British colonization in the 19th century.

See Separate Article: MAJAPAHIT KINGDOM: HISTORY, RULERS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com ; SRIVIJAYA KINGDOM: HISTORY, BUDDHISM, TRADE, ART factsanddetails.com

Tondo

Tondo was a major trading center in northern Luzon, located in the Pasig River delta. The earliest known Philippine historical record, the Laguna Copperplate Inscription (A.D. 900), indirectly refers to Tondo and indicates the existence of political connections among various regional polities as early as the 10th century. [Source: Wikipedia]

By the 1500s, Tondo was ruled by a paramount leader known as a Lakan. It shared a trade monopoly over Ming dynasty goods with the Maynila, highlighting its economic importance. Its trade with China was so significant that the Yongle Emperor appointed a Chinese official to supervise it.

As a sea-centered polity based on Manila Bay, Tondo flourished through extensive trade with China, Japan, and other Asian societies. At its height, it reportedly controlled large parts of Luzon, from Ilocos to Bicol, making it one of the largest precolonial states in the Philippines. Its rulers belonged to the Maharlika warrior class, whom the Spaniards later likened to hidalgos.

Tondo’s culture reflected strong Hindu and Buddhist influences, alongside a productive agricultural and aquaculture economy. It was one of the wealthiest and most prominent kingdoms in precolonial Philippine history.

Tondo also maintained close ties with Japan, which referred to the region as “Luzon.” Japanese trade and cultural exchanges date back centuries, and Philippine-made goods such as Mishima ware reached Japan. Chinese sources likewise mention a polity called “Luzon,” which many historians associate with either Maynila specifically or the broader Tagalog and Kapampangan polities around Manila Bay.

Ma-i

Ma-I (also spelled Ma-yi) was a major maritime trading state with wide international connections. It was documented in Chinese records as early as A.D. 971 and mentioned as late as 1339. Most scholars place it either on Mindoro or in Bay, Laguna. Song dynasty sources, including Volume 186 of the official History of Song, describe Ma-i as a prosperous maritime state visited annually by Chinese traders. [Source: Google AI, Wikipedia]

Ma-i flourished through trade with China, the Ryukyu Islands, Japan, and neighboring Southeast Asian regions. Its exports included kapok cotton, yellow beeswax, tortoiseshell, pearls, medicinal betel nuts, and patterned cloth, which were exchanged for Chinese ceramics and silk, largely through barter. Chinese accounts praised its people as honest and trustworthy and described organized settlements where inhabitants wore cotton garments.

Politically, Ma-i was likely organized as a barangay-type state led by a datu. Unlike other polities that relied on formal tribute missions to attract Chinese trade, Ma-i appears to have been commercially strong enough to sustain relations without heavy dependence on the Chinese imperial court.

Earlier Arab accounts, such as those of Al-Ya'qubi in the 9th century, suggest that Ma-i (possibly identified as “Mayd”) engaged in regional rivalries, including competition involving Brunei and China. Altogether, Ma-i demonstrates that long before Spanish colonization, the Philippines had established, organized, and internationally connected societies integrated into broader Asian trade networks.

Pangasinan

Pangasinan (c. 1406–1576) was a prominent precolonial polity in northern Luzon and independent maritime trading state active in regional and international commerce. As early as 1225, places such as Lingayen Gulf were recorded in Chinese sources like Chu Fan Chih as active trading centers alongside Ma-i (Mindoro or Manila). In the early 15th century, Pangasinan sent tribute missions to China (1406–1411) and maintained trade relations with Japan. Chinese records referred to it as Feng-chia-hsi-lan and highlighted its salt-making industry, beginning with King Kamayin’s tribute embassy to the Chinese emperor. [Source: Wikipedia]

The kingdom occupied what is now Pangasinan province and remained independent until the Spanish conquest. During the 16th century, the Spanish called it the “Port of Japan” due to its strong commercial ties. Local inhabitants wore Southeast Asian attire along with imported Chinese and Japanese textiles, blackened their teeth in keeping with regional customs, and used Chinese and Japanese porcelain. Japanese-style firearms were also reportedly used in naval warfare.

Pangasinan’s economy thrived on trade in gold, slaves, deerskins, civet, and other local goods, attracting merchants from across Asia. Although culturally similar to other Luzon societies, it maintained particularly extensive trade networks with China and Japan.

Butuan

Butuan, often called the Rajahnate of Butuan, was a precolonial Bisaya Hindu polity centered in present-day Butuan City in northeastern Mindanao. Renowned for its gold mining and craftsmanship, it produced gold jewelry, metal tools, and weapons that fueled an extensive trade network across maritime Southeast Asia. Over time, Butuan maintained direct commercial and diplomatic ties with China, Champa, Đ i Vi t, Brunei (Pon-i), Srivijaya, Majapahit, Kambuja, Persia, and areas of present-day Thailand.

Archaeological discoveries—particularly the balangay (large outrigger boats) unearthed along the Libertad (Agusan) River—demonstrate Butuan’s importance as a major trading port in the Caraga region. Excavations in sites such as Suatan and Ambangan revealed burial grounds, habitation areas, and Yuan- and Ming-era porcelains, indicating active trade from at least the 14th to 16th centuries. Additional settlements across Surigao and nearby coastal and riverine communities suggest that Butuan exercised influence over a network of trading communities, though likely with loose control beyond coastal areas.

The origin of Butuan’s name remains debated. Some scholars link it to a rhinoceros ivory seal inscribed in early Javanese or Kawi script that may read “But-wan,” while others associate it with the local fruit batuan or a legendary Datu Bantuan. Another theory connects the name to Hindu-Shaivite traditions and the Golden Tara of Agusan, suggesting possible Indian cultural foundations, though these interpretations remain contested.

Spanish accounts from 1521, including those of Antonio Pigafetta, describe Rajah Siagu ruling Butuan and much of Caraga, while his brother Rajah Colambu ruled Limasawa. However, later historians note that such “kingdoms” were likely small maritime chiefdoms with limited control over inland areas. Upland groups such as the Manobo and Mandaya were often independent and at times hostile to Butuan’s coastal rulers. Spanish reports from the 1570s also mention gold-rich settlements in the broader Surigao area.

Chinese records confirm Butuan’s diplomatic contact with the Song dynasty as early as 1001 AD, when tribute missions were sent to the imperial court. Identified in Chinese texts as Buotuan ( ), it was described as a prosperous Hindu kingdom. A ruler named Kiling sought diplomatic parity with Champa at the Chinese court, though the request was denied. Historical and genetic studies indicating South Asian influences in the region further support evidence of early Indian cultural connections, highlighting Butuan’s role as a significant, internationally engaged precolonial state.

Cebu

Kingdom of Cebu was a precolonial state founded by Sri Lumay (Rajamuda Lumaya), said to be of mixed Malay and Tamil origin from Sumatra. Chinese records referred to it as “Sokbu” (Hokkien) or “Suwu” (Mandarin), a name appearing as early as 1225 in the Zhufan Zhi, indicating Cebu’s early prominence in regional trade. [Source: Wikipedia]

The rajahnate ruled from the Sanskrit-named capital Singhapala (“Lion City”), reflecting strong Indian cultural influence. Cebu maintained alliances with the Rajahnate of Butuan and Indianized Kutai in South Borneo, and it engaged in conflicts with Maguindanao slave traders. Its power declined after internal resistance led by Datu Lapulapu.

Cebu enjoyed diplomatic ties with regional powers, including Siam (Thailand), as noted during Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition, which recorded a Siamese tribute mission to Rajah Humabon. The kingdom exported agricultural goods such as rice, millet, maize, fruits, sugarcane, ginger, honey, palm wine, and gold, underscoring its role as a thriving maritime trade center.

Early Filipino Sultanates

Sulu Sultanate was a Sunni Muslim Tausug state that exercised authority over the Sulu Archipelago, coastal parts of southern Mindanao, and sections of Palawan in the Philippines, as well as areas of northeastern Borneo, including parts of modern-day Sabah and North Kalimantan. It grew wealthy from the spice trade, pearling, weapons sales and the slave market. As head of an Islamic polity, the sultan embodied both political and religious authority. Official genealogies traced his lineage to the Prophet Muhammad, and he was expected to exemplify moral virtue and piety. Mirroring the political hierarchy was a religious structure that converged in the person of the sultan and extended downward through the kadi (judge), ulama (scholars), imam, hatib (preacher), and bilal (caller to prayer), who served as legal advisers and mosque officials at various levels of society. [Source: Wikipedia, Clifford Sather, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The sultanate was founded either in 1405 or in 1457 by Sharif ul-Hashim, a Johore-born explorer and Sunni religious scholar. Upon establishing rule in Buansa, Sulu, he assumed the regnal name Paduka Mahasari Maulana al-Sultan Sharif ul-Hashim. Under his leadership, the polity consolidated Islamic authority in the region. In 1578, the Sulu Sultanate asserted its independence from the Bruneian Empire. The Sulu Sultanate is possibly referenced in the Javanese epic Kakawin Nagarakretagama, written in 1365, where a polity called Solot is listed among the territories within the Tanjungnagara (Kalimantan–Philippines) region said to fall under the mandala sphere of influence of the Majapahit Empire. Until the mid-nineteenth century, the Sulu Sultanate conducted extensive trade with China in pearls, birds’ nests, trepang (sea cumcumber), camphor, and sandalwood.

Sultanate of Maguindanao emerged in the late 15th or early 16th century when Shariff Mohammed Kabungsuwan of Johor introduced Islam to Mindanao. After marrying Paramisuli, an Iranun princess, he established the sultanate, which came to dominate much of coastal Mindanao. It remained influential until the 19th century and maintained active trade and diplomatic relations with Chinese, Dutch, and British merchants. Its principal exports included rice, wax, tobacco, clove and cinnamon bark, coconut oil, sago, beans, tortoiseshell, bird’s nests, and ebony. [Source: Wikipedia]

Confederate States of Lanao were founded in the 16th century under the broader influence of Shariff Kabungsuwan’s Islamization efforts and were closely connected were the Sultanate of Maguindanao. Unlike the more centralized sultanates of Sulu and Maguindanao, Lanao developed a decentralized political system divided into the Four Principalities (Pat a Pangampong a Ranao), composed of sixteen royal houses with defined territories. This structure emphasized shared authority, unity, patronage, and kinship among ruling clans. By the 16th century, Islam had expanded beyond Mindanao to parts of the Visayas and Luzon, reshaping the political and religious landscape of the region.

See Separate Articles: ETHNIC GROUPS IN SULU ISLANDS factsanddetails.com; MORO (MUSLIM ETHNIC GROUPS) ON MINDANAO factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Library of Congress, Philippines Department of Tourism, Philippines government websites, Encyclopedia.com, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Wikipedia, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, UNESCO, National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) the official government agency for culture in the Philippines), Lonely Planet Guides, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, The Conversation, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Google AI, and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated February 2026