MALAYS

Malays are an Austronesian ethnoreligious group native to the Malay Peninsula, eastern Sumatra, coastal Borneo. Also known as Malayans, Melayu and Orang Melayu, they have traditionally been known as a coastal-trading community with fluid cultural characteristics. They absorbed, shared and transmitted numerous cultural features of other local ethnic groups, such as those of Minangkabau and Acehnese.

Most of the people in Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines are either Malays or closely related to them. Some are similar historically, linguistically and genetically. Some are somewhat different historically and genetically but at some point adopted a Malay language. Others are similar historically and genetically but at some point adopted a language somewhat different from Malay. The term Malay also has some issues because of its association with 19th century ideas about race.

The epic literature Malay Annals traces the origin of the term “Melayu” to a small river called Sungai Melayu (Melayu River) in Sumatra, Indonesia. The text claims that this river flowed into the Musi River in Palembang, although in reality it flows into the Batang Hari River in Jambi. The name is believed to come from the Malay word melaju, formed from the verbal prefix me- and the root word laju, meaning “to accelerate” or “to move swiftly.” The term likely referred to the strong, fast-moving current of the river. The original Malay Annals text has undergone numerous changes. The oldest surviving version dates to 1612, through the rewriting effort commissioned by the then regent of Johor, Raja Abdullah. [Source: Wikipedia]

The many Malay subgroups exhibit considerable linguistic, cultural, artistic, and social diversity, mainly due to hundreds of years of immigration and assimilation of various ethnic groups and tribes within Maritime Southeast Asia. The Malay population is historically descended primarily from earlier Malayic-speaking Austronesians and Austroasiatic tribes. These tribes founded several ancient maritime trading states and kingdoms, including Brunei, Kedah, Langkasuka, Gangga Negara, Chi Tu, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Pahang, Melayu, and Srivijaya.

Despite their diversity, Malay groups share Austronesian linguistic roots, long-standing maritime connections, and related cultural traditions. Historically, their societies were influenced first by Hindu-Buddhist civilizations and later more profoundly shaped by the spread of Islam, though local customs continue to vary by region.

RELATED ARTICLES:

AUSTRONESIAN PEOPLE OF THE PACIFIC, INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, TAIWAN AND THE PHILIPPINES: ORIGIN, HISTORY, EXPANSION factsanddetails.com

EARLY HISTORY OF MALAYSIA: HOMINIDS, FIRST PEOPLE, PROTO-MALAYS factsanddetails.com

AUSTRONESIAN PEOPLE OF THE PACIFIC, INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, TAIWAN AND THE PHILIPPINES: ORIGIN, HISTORY, EXPANSION factsanddetails.com

EARLY KINGDOMS, EMPIRES AND THE ARRIVAL OF ISLAM IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com

EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

EARLIEST PEOPLE OF INDONESIA: NEGRITOS, PROTO-MALAYS, MALAYS AND AUSTRONESIAN SPEAKERS factsanddetails.com

OLDEST CULTURES IN INDONESIA AND PEOPLE THERE BEGINNING 10,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

FIRST HOMININS IN THE PHILIPPINES: 709,000-YEAR-OLD TOOLS, HOMO LUZONENSIS TABON MAN factsanddetails.com

EARLY HISTORY OF THE PHILIPPINES: MIGRATIONS, DISPLACEMENTS, DNA, factsanddetails.com

PHILIPPINES BEFORE THE ARRIVAL OF THE SPANISH factsanddetails.com

PRE-COLONIAL FILIPINO STATES factsanddetails.com

PHILIPPINES HISTORY: NAMES, THEMES, TIMELINE, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

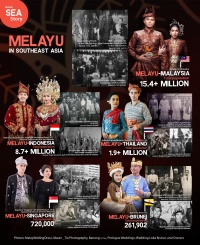

Where Malays Live

Malays make up more than half of the population of Peninsular Malaysia and are found in large numbers in Borneo in East Malaysia (Sabah and Sarawak), along the coasts of Sumatra and as far as the Sulu Sea in the southern Philippines. [Source: Manning Nash, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Malays also live well as the smaller islands between peninsular Malaysia, Borneo and Sumatra such as the Riau Archipelago near Singapore. Today, these areas fall within several modern states: Malaysia; Brunei Darussalam and Indonesia (including eastern and southern Sumatra,Islands, the Bangka Belitung, West Kalimantan, and the coast of East Kalimantan). Their range extends into Southeast Asia: southern Thailand (Pattani, Satun, Songkhla, Trang, Krabi, Yala, and Narathiwat); Singapore; and the southernmost part of Myanmar (Tanintharyi).

Malay groups are one of Indonesia's largest indigenous populations. Numbering over 8 million people, they make up roughly 3.7 percent of the population and are primarily concentrated along the coastal regions of Sumatra, Kalimantan, and the Riau Islands. As a predominantly Muslim community, they share close ties with the broader Malay world, including Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei.

Malay groups in the Philippines are primarily represented by the Moro people, the indigenous Muslim populations in Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan who share strong cultural, religious, and ancestral ties with the wider Malay world. Comprising roughly 13 major ethno-linguistic groups (such as the Tausug, Maranao, Maguindanaon, Sama-Bajaw, Iranun, Yakan), they maintain traditions distinct from the largely Christianized, Spanish-influenced majority.

In Malaysia, distinct regional Malay communities include the Kedahan, Kelantanese, Melaka, and Pahang Malays, each with their own dialects and cultural traditions. The region also includes indigenous or Proto-Malay groups, often referred to as Orang Asli or Orang Asal, such as the Jakun, Temuan, Semelai, and Temoq. Coastal and island-oriented communities include the Bajau, Orang Laut, Suluk, and Molbog, many of whom have strong maritime traditions. In Borneo, important subgroups include the Iban, Dusun, Murut, Kadazan, and Melanau peoples.

Broader Uses of the Term Malay

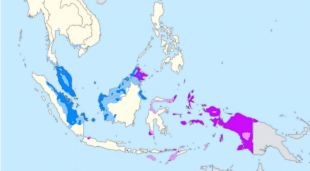

Malay language as the majority (dark blue)

Malay language as the minority (light blue)

Malay-based creole languages (purple)

The term “Malay” is sometimes used broadly to describe peoples within a wider cultural region historically known as the "Malay world", which included the descendants proto-Malays and Malay immigrants from the Malacca Sultanate called anak dagang, meaning "traders." These include groups in southern Thailand and Myanmar. Anak dagang are predominantly from the Indonesian archipelago and include the Acehnese, the Banjarese, the Bawean, the Bugis, the Mandailing, the Minangkabau, and the Javanese.

The “Malay Archipelago” embraces Indonesia and other places nearby (See Below). Sometimes most of the groups there are considered Malays but often not. Javanese, for example, the largest ethnic group in Indonesia, native to Java, are generally regarded as a distinct Austronesian ethnic group and are not ethnically Malay, though they share linguistic and cultural ties. In Malaysia and Singapore, they are often classified or assimilate as "Malay" due to shared religion (Islam) and culture. The Javanese and Malay cultures are distinct, with different languages, although both are within the Malayo-Polynesian family.

Malay-speaking peoples number roughly 250 to 350 million, and include many of the people in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, southern Thailand, and parts of the Philippines. They are primarily of Austronesian descent and share a common linguistic heritage rooted in the Malay language, known as Bahasa Melayu or Bahasa Indonesia. The high number Malay-speaking peoples is largely driven by the adoption of Bahasa Indonesia, the standardized national form of Malay in Indonesia. Many speakers of Bahasa Indonesia speak it as second language and their first language, such as Javanese or Sundanese, may not be considered a Malay language.

Malay Archipelago is the archipelago between Mainland Southeast Asia and Australia.The name was taken from the 19th-century European concept of a Malay race, later based on the distribution of Austronesian languages. Indonesia makes up most of the Malay Archipelago but name is controversial there Indonesia due to its ethnic connotations and colonial undertones, which can overshadow the country's diverse cultures. The Malay Archipelago is situated between the Indian and Pacific oceans and embraces over 25,000 islands and islets. It is the largest archipelago by area and fifth by number of islands in the world. It includes Brunei, East Timor, Indonesia, East Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, and Singapore. The term is largely synonymous with Maritime Southeast Asia. Ethnic groups in the Malay Archipelago are diverse and predominantly Austronesian. Major communities include the Javanese, Sundanese, Bugis, Minangkabau, Banjarese, and Acehnese. Sometimes these groups are considered Malay but often they are not although they are regarded as closely related to Malay.

Austronesian-Speaking People

Austronesian languages are a large language family spoken by around 400 million people today across Southeast Asia and the Indo-Pacific, including Taiwan, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines Madagascar, and Oceania. Key languages include Malay, Javanese, and Sundanese in Indonesia, and Tagalog, Cebuano, and Ilocano in the Philippines.

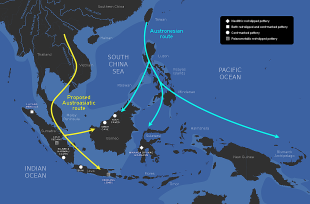

Austronesian-speaking peoples originated in southern China but developed as a distinct group in Taiwan. Beginning 4,000–5,000 years ago, they launched a major seafaring expansion, island-hopping through the Philippines into the central Indonesian archipelago. From there they spread west into Borneo, Java, and Sumatra—where they encountered Austroasiatic migrants—and east into regions inhabited by earlier Australoid populations.

Over time, Austronesian groups became dominant across Indonesia. They largely replaced Australoid populations (now found mainly in the east) and influenced Austroasiatic-speaking groups to the point that western Indonesia eventually became entirely Austronesian-speaking, despite some populations retaining notable Austroasiatic genetic markers. Genetic studies show strong Austronesian ancestry throughout central and eastern Indonesia. By around 2000 BCE, Austronesians had expanded across Maritime Southeast Asia, into Oceania, and eventually as far as Madagascar. Today, they form the majority of Indonesia’s, Malaysia’s and the Philippines’s population.

See Separate Article: AUSTRONESIAN PEOPLE OF THE PACIFIC, INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, TAIWAN AND THE PHILIPPINES: ORIGIN, HISTORY, EXPANSION factsanddetails.com

Malay History

The Malays originated from the migration from Yunnan and Taiwan the southward and eastward to the Malay Peninsula, present-day Indonesia and the Philippines and the Pacific Islands, where Malayo-Polynesian languages still predominate. Proto- Malays arrived in several waves, probably continuously, pushing aside previous inhabitants — Negritos and Orang Asli (aboriginals). Early Chinese and Indian visitors and voyagers, beginning around 600 B.C. reported on Malay villages that farmed and used metal. The earliest historical record on the peninsula dates to around A.D. 1400. [Source: Manning Nash, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Malay culture in present-day Indonesia was initially strongly influenced by India. There is no definitive evidence regarding the earliest Indian voyages across the Bay of Bengal, but conservative estimates place the first arrivals on Malay shores at least 2,000 years ago. The discovery of jetty remains, iron smelting sites, and a clay brick monument dating back to A.D. 110 in the Bujang Valley shows that a maritime trading route with the South Indian Tamil kingdoms had been established by the second century. [Source: Wikipedia]

The rise of the Malacca Sultanate (1402–1511) marked a turning point in Malay history though Malaya was mentioned in the maritime Sumatra-based Srivijaya Empire around A.D. 700. Malacca was a trading empire, which controlled the Strait of Malacca, was the center of the diffusion of Islam throughout Malaysia. This peaceful spread was led by teachers and Sufis. From the 1500s to the 1800s, competing groups such as the Acehnese, Bugis, and Minangkabau struggled for dominance on the peninsula while Melaka struggled with the Dutch and other European powers who sought to control commerce in the strait.

The Malacca Sultanate left a lasting political and cultural legacy. During this period, key elements associated with Malay identity—Islam, the Malay language, and shared customs—became firmly established, contributing to the formation of the Malays as a major ethnoreligious group in the region. Malacca also set enduring standards in literature, architecture, cuisine, dress, performing arts, martial arts, and royal court traditions that later Malay sultanates followed.

There were other powerful Malay sultanates such as the ones in Johor in peninsular Malaysia, Aceh in Sumatra and and Brunei in Borneo. During the golden age of the Malay sultanates many communities—including groups such as the Batak, Dayak, Orang Asli, and Orang Laut—underwent processes of Islamization and Malayization. Over time, the term “Malay” broadened to include other ethnic groups within the wider “Malay world.” Today, this broader usage is largely limited to Malaysia and Singapore, where descendants of immigrant communities from the Indonesian archipelago—such as the Acehnese, Banjarese, Bawean, Bugis, Mandailing, Minangkabau, and Javanese—are often referred to as anak dagang (“traders”).

Proto-Malay Models

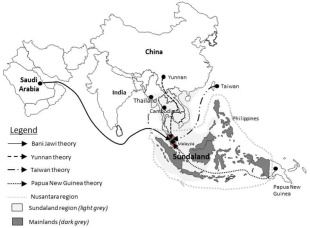

Migration pattern showing the origin of Malays according to some theories; The highlighted light grey region shows Sundaland during Last Glacial Maximum before the rise of sea levels; The rise in ocean level had submerged Sundaland and spread people to mainlands (Indonesia, Borneo, Philippines and Malaysia) today Researchgate

Also known as Melayu asli (aboriginal Malays) or Melayu purba (ancient Malays), the Proto-Malays are of Austronesian origin and thought to have migrated to the Malay archipelago in a long series of migrations between 2500 and 1500 BC. The Encyclopedia of Malaysia: Early History, has pointed out a total of three theories of the origin of Malays: 1) The Yunnan Theory , or Mekong river migration (published in 1889) : The theory of Proto-Malays originating from Yunnan is supported by R.H Geldern, J.H.C Kern, J.R Foster, J.R Logen, Slamet Muljana and Asmah Haji Omar. Other evidences that support this theory include: stone tools found in Malay Archipelago are analogous to Central Asian tools, similarity of Malay customs and Assam customs. [Source: Wikipedia +]

2) New Guinea theory (published in 1965): The proto-Malays are believed to be seafarers knowledgeable in oceanography and possessing agricultural skills. They moved around from island to island in great distances between modern day New Zealand and Madagascar, and they served as navigation guides, crew and labour to Indian, Arab, Persian and Chinese traders for nearly 2000 years. Over the years they settled at various places and adopted various cultures and religions. +

3) Taiwan theory (published in 1997): The migration of a certain group of Southern Chinese occurred 6,000 years ago, some moved to Taiwan (today's Taiwanese aborigines are their descendents), then to the Philippines and later to Borneo (roughly 4,500 years ago) (today's Dayak and other groups). These ancient people also split with some heading to Sulawesi and others progressing into Java, and Sumatra, all of which now speaks languages that belongs to the Austronesian Language family. The final migration was to the Malay Peninsula roughly 3,000 years ago. A sub-group from Borneo moved to Champa in modern-day Central and South Vietnam roughly 4,500 years ago. There are also traces of the Dong Son and Hoabinhian migration from Vietnam and Cambodia. All these groups share DNA and linguistic origins traceable to the island that is today Taiwan, and the ancestors of these ancient people are traceable to southern China. +

The Deutero-Malays are Iron Age people descended partly from the subsequent Austronesian peoples who came equipped with more advanced farming techniques and new knowledge of metals. They are kindred but more Mongolised and greatly distinguished from the Proto-Malays which have shorter stature, darker skin, slightly higher frequency of wavy hair, much higher percentage of dolichocephaly and a markedly lower frequency of the epicanthic fold. The Deutero-Malay settlers were not nomadic compared to their predecessors, instead they settled and established kampungs which serve as the main units in the society. These kampungs were normally situated on the riverbanks or coastal areas and generally self-sufficient in food and other necessities. By the end of the last century BC, these kampungs beginning to engage in some trade with the outside world. The Deutero-Malays are considered the direct ancestors of present-day Malay people. Notable Proto-Malays of today are Moken, Jakun, Orang Kuala, Temuan and Orang Kanaq. +

Proto Malays, from Yunnan, China?

Possible language family homelands and the spread of rice into Southeast Asia (around 5,500–2,500 years ago); The approximate coastlines during the early Holocene are shown in lighter blue

Anthropologists have traced the migration of Proto Malays, who were seafarers, to some 10,000 years ago when they sailed by boat (canoe or perahu) along the Mekong River from Yunnan to the South China Sea and eventually settled down at various places. The Mekong River is approximately 4180 kilometers in length. It originates in from Tibet and runs through Yunnan province of China, Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and South Vietnam. [Source: Wikipedia]

Inhabitants of early Yunnan may be traced back into prehistory from a homo erectus fossil, 'Yuanmou Man', which was unearthed in the 1960s. In year 221 BC, Qin Shihuang conquered Yunnan and unified China. Yunnan has since become a province of China. They were the ancestors of rice eating peoples, with their culture of cultivating rice spread throughout the entire region. The native name of the Mekong River peoples' home in Yunnan is Xishuangbanna (Sipsongpanna) which literally means "twelve thousand rice fields", it is the home of the Dai minority. Xishuangbanna sits at a lower altitude than most of the Yunnan mountainous ranges. Yunnan women on the street, wearing batik & sarong. Photo taken at the city of Jinghong (2004). Yunnan migration theory

The theory of Proto Malay originating from Yunnan is supported by R.H Geldern, J.H.C Kern, J.R Foster, J.R Logen, Slametmuljana and Asmah Haji Omar. The Proto Malay (Melayu asli) who first arrived possessed agricultural skills while the second wave Deutero Malay (mixed blood) who joined in around 1500 B.C. and dwelled along the coastlines have advanced fishery skills. During the migration, both groups intermarried with peoples of the southern islands, such as those from Java (Indonesian), and also with aboriginal peoples of Australoid, Negrito and Melanesoid origin.

Other evidences that support this theory include: 1) Stone tools found at Malay archipelago are analogous to Central Asian tools. 2) Similarity of Malay customs and Assam customs. 3) Malay language & Cambodian language are kindred languages because the ancestral home of Cambodians originated from the source of Mekong River. The Kedukan Bukit Inscription of A.D. 682 found at Palembang and the modern Yunnan Dai minority's traditional writings belong to the same script family, Pallava, also known as Pallava Grantha. Dai ethnic (or Dai minority) of Yunnan is one of the aboriginal inhabitants of modern Yunnan province of China.

Arrival of Malay-Related People in the Philippines, Borneo and Malaysia

It is believed that around 3000 B.C. Malay people—or people that evolved into the Malay tribes that dominate Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines—arrived in the Philippines. About 2300 years ago, in another migration, Malay people from the Asian mainland or Indonesia arrived in the Philippines and brought a more advanced culture; iron melting and production of iron tools, pottery techniques and the system of sawah's (rice fields). Additional migrations took place over the next millennia. Many believe the first Malays were seafaring, tool-wielding Indonesians who introduced formal farming and building techniques.

By 3000 B.C.,Austronesian peoples possibly from the Philippines had arrived in Borneo. Archaeological and physical anthropological evidence, together with historical and comparative studies, suggest that the first Austronesia groups migrated into northern Borneo in successive waves around 4,000 to 5,000 years ago, and possibly earlier. These early migrants introduced a Neolithic, food-producing way of life centered on swidden cultivation, supplemented by hunting and foraging. Beginning in the sixth century A.D., iron metallurgy provided the people in Borneo with tools to clear the dense interior forests for rice and taro cultivation. These crops were more nutritious than their former staple, sago palm starch.[Source: Thomas Rhys Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993^^]

The indigenous groups on the Malaysian peninsula can be divided into three ethnicities, the Negritos, the Senois, and the proto-Malays. The first inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula were most probably Negritos. These Mesolithic hunters were probably the ancestors of the Semang, an ethnic Negrito group who have a long history in the Malay Peninsula. The Senoi appear to be a composite group, with approximately half of the maternal DNA lineages tracing back to the ancestors of the Semang and about half to later ancestral migrations from Indochina. Scholars suggest they are descendants of early Austroasiatic-speaking agriculturalists, who brought both their language and their technology to the southern part of the peninsula approximately 4,000 years ago. They united and coalesced with the indigenous population. . [Source: Wikipedia]

The Proto Malays have a more diverse origin, and were settled in Malaysia by 1000BC. Although they show some connections with other inhabitants in Maritime Southeast Asia, some also have an ancestry in Indochina around the time of the Last Glacial Maximum, about 20,000 years ago. Anthropologists support the notion that the Proto-Malays originated from what is today Yunnan, China. This was followed by an early-Holocene dispersal through the Malay Peninsula into the Malay Archipelago.

Around 300 BC, they were pushed inland by the Deutero-Malays, an Iron Age or Bronze Age people descended partly from the Chams of Cambodia and Vietnam. The first group in the peninsula to use metal tools, the Deutero-Malays were the direct ancestors of today's Malaysian Malays, and brought with them advanced farming techniques. The Malays remained politically fragmented throughout the Malay archipelago, although a common culture and social structure was shared.

From peninsular Malaysia or Borneo Austronesian people made their way to the islands of present-day Indonesia, which begin not far from Malaysia. Examples of Austronesian presence the use throughout the archipelago of Austronesian languages, the spread of rice agriculture and sedentary life, and of ceramic and (later) metal technologies; the expansion of long-distance seaborne travel and trade; and the persistence of diverse but interacting societies with widely varying levels of technological and cultural complexity. [Source: Library of Congress]

Malay Language

Malay belongs to the Austronesian (Malayo-Polynesian) family of languages, which extends from mainland Southeast Asia to Easter Island in the Pacific. Malay spoken in Malaysia (Bahasa Melayu) is similar to Malay spoken in Indonesia (Bahasa Indonesian) in the same way that British and American English are similar. However, Indonesian shows the effects of long contact with Dutch in its structure and vocabulary, while Malay exhibits English influences. Malay is written in a Latin alphabet (Rumi) and a derived Indian script (Jawi). [Source: Manning Nash, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Areas where Malay is spoken:

Indonesia (blue)

Malaysia (dark green)

Singapore and Brunei, where Standard Malay is an official language (light green)

East Timor, where Dili Malay is a Malay creole language and Indonesian is used as a working language (light blue)

Southern Thailand and the Cocos Islands, where other varieties of Malay are spoken (yellow)

Malay originated from the Proto-Malayo-Polynesian language spoken by early Austronesian settlers in Southeast Asia. It later developed into Old Malay as Indian cultural and religious influences entered the region. Although Old Malay contained terms that survive today, it would be largely unintelligible to modern speakers. The language became more recognizable in its written Classical Malay form, with the earliest known example dating to A.D. As Islam spread throughout Southeast Asia, Malay absorbed significant Arabic and Persian vocabulary and evolved into Classical Malay. During the 15th-century Malacca Sultanate, one literary dialect became dominant. The language adopted the Arabic-based Jawi script, replacing the earlier Kawi script, and incorporated many Islamic religious and cultural terms while discarding much of its earlier Hindu-Buddhist vocabulary. Malay became an important medium for Islamic teaching and communication across the region.

At the height of Malacca’s influence, Malay spread widely as a regional lingua franca. A simplified trade variety known as Bazaar Malay (Bahasa Melayu pasar) emerged alongside the more formal Classical Malay (Bahasa Melayu tinggi). Over time, this trade language creolized and gave rise to several new Malay-based languages, including Ambonese Malay, Manado Malay, and Betawi. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century European writers such as Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, Christophorus Thomassin, and George Henrik Werndly described Malay as the “language of the learned in all the Indies,” comparing its role to that of Latin in Europe. It was widely used throughout the Malay Archipelago during the British and Dutch colonial periods. In contrast, in the Spanish East Indies (the Philippines), extensive Hispanization contributed to the decline of Malay there.

The dialect of the Johor Sultanate, successor to the Malacca Sultanate, became the foundation of standard Malay in Singapore and Malaysia and also influenced the development of standardized Indonesian. Alongside this standard form, many regional dialects developed, including those of Bangka, Brunei, Jambi, Kelantan, Kedah, Negeri Sembilan, Palembang, Pattani, Sarawak, and Terengganu. Historically, Malay was written in scripts such as Pallava, Kawi, and Rencong. With the spread of Islam, the Arabic-based Jawi script was adopted and remains in official use in Brunei and as an alternative script in Malaysia. From the 17th century onward, British and Dutch colonial influence encouraged the adoption of the Latin-based Rumi script, which eventually became the modern official writing system for Malay in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia, and a co-official script in Brunei.

Islamisation of the Malays

Islam reached the Malay Peninsula as early as the 12th century, with the Terengganu Inscription Stone providing early archaeological evidence. By the 15th century, Malacca became the main center of Islamisation in the region, shaping a classical Malay identity closely tied to Islam, the Malay language, and shared cultural traditions. Even after its fall to the Portuguese in 1511, Malacca remained a political and cultural model for later Malay states. [Source: Wikipedia]

Malacca’s influence spread through trade and religious missions, promoting Malayisation across the archipelago. Successor states such as the Johor Sultanate and the Perak Sultanate continued its administrative and cultural legacy. During this period, Islam became a defining marker of Malay identity and a foundation of Malay sociocultural structure.

At the same time, the Bruneian Empire rose as a major power in Borneo. Closely linked to Malacca through marriage and religion, Brunei adopted Islamic governance and expanded its influence across Borneo and into parts of the Philippines, including Luzon and Mindanao. Through trade, political alliances, and river-based administration, Brunei helped extend Islamisation and Malayisation in the region. Numerous other Malay sultanates also emerged between the 12th and 18th centuries across the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, and Borneo. These included Kedah, Kelantan, Patani, Jambi, Palembang, and Pontianak, among others. Together, these states strengthened Islamic rule, expanded trade networks, and reinforced Malay political and cultural traditions throughout the Malay world.

Most Malays are Sunni Muslims. While many observe the Five Pillars of Islam faithfully, others are less strict in their practice. Religious devotion is often expressed through sincere inner intention, known as niat, and through participation in Sufi brotherhoods. In the northeastern Malay regions, Islamic teachings are commonly transmitted in traditional residential boarding schools called pondok, led by respected religious teachers known as tok guru. [Source: Manning Nash, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

In recent decades, especially among university students and younger generations, there has been a growing movement to return to a stricter and more purified form of Islam. This revivalist movement, known as dakwah (from the Arabic term meaning a “call” back to religion), emphasizes deeper commitment to Islamic principles. The Malay ritual calendar is largely structured around Islamic holy days and observances. Beneath orthodox Islamic practices, however, remain elements of earlier Hindu and animistic beliefs. Spirits known as hantu-hantu—including ghosts and supernatural beings of pre-Islamic origin—are still acknowledged in popular belief. These spirits are generally avoided, appeased, or warded off, reflecting spiritual concepts similar to those found in other Southeast Asian cultures.

Malay Family, Marriage and Kinship

The most common type of family among the Malays is a small nuclear family made up of parents and their children, living in their own home. Sometimes extended families live together for a time, but this is usually temporary, and eventually the couple forms their own separate household. [Source: Manning Nash, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Marriage is expected of all adults. Islamic law allows a man to have up to four wives, but most marriages involve only one husband and one wife. A couple marries by registering with a religious official, usually the local imam. A woman must have the permission of her male guardian to marry. Many marriages are arranged by families, but the couple must know about and agree to the marriage. Before the wedding, both families exchange gifts, including money or property from the groom’s side and property from the bride’s side. The wedding ceremony is often celebrated with a bersanding, a formal sitting ceremony inspired by old royal Hindu-style weddings, followed by a feast. Divorce is relatively easy and happens fairly often. In some Malay states like Kelantan, divorce rates are high, partly because a husband can end a marriage simply by declaring his intention to do so.

Adoption is common in Malay families. Couples who cannot have children often ask relatives if they can raise one of their children, and this request is usually accepted. Having children is important, especially for taking part in village activities that involve sharing food and gifts, which childless couples might otherwise miss. Children are greatly valued. When young, they are treated gently and allowed much freedom, but as they grow older, they are taught to speak politely and behave respectfully. A well-raised child shows budi bahasa, meaning good manners and proper character. A child with bad behavior is criticized as kurang ajar, meaning poorly taught or lacking good upbringing.

Most Malays do not belong to formal family clans that trace ancestry through only the father’s or mother’s side. Family ties are generally recognized through both parents’ sides equally. An exception is the Minangkabau Malays of Negeri Sembilan, who follow customs that trace family line and property through the mother’s side. In general Malay practice, inheritance follows Islamic rules, though property is often divided equally among children. Malay kinship terms depend on generation (such as grandparents, parents, children), gender (male or female), and whether someone is older or younger. Older and younger siblings are clearly distinguished. When people have titles, jobs, religious honors, or social ranks, these are often used instead of personal names or family terms.

Malay Settlements and Economic Activity

Traditional Malay villages, called kampong, have typically been built along river mouths, but villages have also been built on beaches, or roads. Village consists of houses—often built on stilts—surrounded by fruit trees, with rice fields outside the residential area. Most villages do not have public buildings, except for a small prayer house (surau) or mosque. Towns and cities developed mainly through trade, government activity, transportation, and immigrant communities. Markets in towns serve as centers where goods from the countryside are brought in by boat, truck, bus, or train. Urban areas are growing quickly, making cities the fastest-expanding type of settlement in Malaysia. [Source: Manning Nash, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Traditional Malay houses are built with wooden frames, sloping roofs, front porches, high ceilings, and many windows for airflow. They are often decorated with detailed wood carvings, which reflect the owner’s social status. Modern buildings sometimes still follow these traditional design features.

Wet-rice farming is the main occupation of many Malays, now often supported by modern irrigation that allows two harvests a year. Most of the rice is consumed locally. Many rice farmers work as tenants or sharecroppers rather than landowners. Fishing is another important livelihood, usually done on a small commercial scale. Malays also work in transportation, local markets (pasar), government service, and other salaried jobs in towns and cities.

Because rice farming provides relatively low income and is largely practiced by Malays, their average income has historically been lower than that of Chinese and Indian communities. The Malaysian government has adopted policies aimed at reducing this income gap.

Malay Culture

Many traditional Malay arts and crafts continue to thrive, especially in places where Malay populations are concentrated. Batik cloth is still made through weaving and dyeing, and skilled artisans produce silver, brass, and iron items for sale. A popular traditional performance is wayang kulit, a shadow puppet show based on old Hindu stories. These performances can last several nights, and the puppet master is paid either by a host or through community contributions. Traditional games such as top-spinning and kite-flying remain popular in some places. Bersilat, the Malay martial art, has also experienced a revival in both rural and urban areas. [Source: Wikipedia, Manning Nash, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Malay literature, both oral and written, is rich and varied. It includes stories about all levels of society, from common servants to rulers, helping shape Malay cultural identity. The Malay language, known for its smooth and rhythmic quality, is especially suited to poetry. Popular poetic forms include the pantun, syair, and gurindam.

One of the most important works of Malay literature is the Malay Annals, also known as Sulalatus Salatin. It was described by the scholar Richard Olaf Winstedt as the most famous and distinctive of all Malay literary works. Although its exact origins are unclear, it was compiled in 1612 under the order of Alauddin Riayat Shah III, with editing overseen by Tun Sri Lanang. The text provides valuable details about Malay royal courts, including palace design during the reign of Sultan Mansur Shah of Malacca.

Malay architecture has been shaped by Chinese, Indian, and European influences. Traditionally, most buildings were constructed from wood, though stone structures—especially religious buildings—date back to earlier Malay kingdoms and the Srivijaya period.

In traditional healing practices, spiritual beliefs also play an important role. A healer known as a bomoh or dukun performs curing ceremonies that may involve trance and ritual acts to remove illness believed to be caused by spirits. These healers also use herbal medicines and traditional poisons in treatment. Bone-setting is common, and traditional midwives continue to assist in many childbirths.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated February 2026