ETHNIC GROUPS IN SUMATRA

Sumatra is home to a large number of ethnic group, with some anthropologists counting more than 100 indigenous ethnicities on the island. Major groups include the Batak, Minangkabau, Acehnese, Malays, Nias, and Lampung peoples, alongside long-established migrant communities such as Javanese, Sundanese, Chinese, and Indians. Each group contributes its own language, social organization, and cultural traditions, creating one of the richest cultural mosaics in Indonesia.

Among the indigenous peoples, the Batak of North Sumatra comprise several related groups—such as the Toba, Karo, and Mandailing—known for their strong clan systems and, in many areas, predominantly Christian traditions. The Minangkabau of West Sumatra are renowned for maintaining the world’s largest surviving matrilineal society, in which property and lineage are passed through women. In Aceh, the Acehnese form a culturally distinct group with strong Islamic traditions and historical links to the wider Indian Ocean world, while inland communities such as the Gayo and Alas maintain their own languages and customs.

Other indigenous populations are concentrated along Sumatra’s coasts and outer islands. Malay communities inhabit much of the eastern and coastal regions and share close cultural ties with Malays in neighboring Malaysia. Off the western coast, the peoples of Nias and the Mentawai Islands preserve distinctive traditions, with Nias historically known for warrior culture and megalithic heritage, and Mentawai society recognized for its tattooing and forest-based way of life. Additional groups such as the Rejang in Bengkulu and the Lampung in the south further add to the island’s ethnic complexity.

Non-indigenous populations are also significant. Large numbers of Javanese migrated to Sumatra during the colonial period and later government-sponsored resettlement programs, particularly to plantation and agricultural areas. Sundanese communities from West Java are present in several regions, while Chinese Indonesians form long-established urban and commercial communities, especially in cities such as Medan, many tracing their ancestry to nineteenth-century migrants.

This diversity is reflected in regional patterns across the island. North Sumatra is characterized by a Batak majority alongside substantial Javanese, Chinese, and Nias populations. West Sumatra remains overwhelmingly Minangkabau in composition, while Aceh is dominated by the Acehnese, with important minority groups such as the Gayo and Alas in the highlands. Together, these patterns underscore Sumatra’s remarkable ethnic and cultural plurality.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BATAKS: GROUPS, HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND WERE THEY REALLY CANNIBALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK RELIGION: CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, BURIALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, KINSHIP factsanddetails.com

BATAK LIFE: HOUSES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK factsanddetails.com

BATAK CULTURE: MUSIC, ART, FOLKLORE, CRAFTS AND LIFE-SIZE PUPPETS factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, SOCIETY, FAMILIES factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI RELIGION CHRISTIANITY, SPIRITS, SHAMAN factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI LIFE: HOUSING, FOOD, HUNTING, MODERNIZATION factsanddetails.com

MENTAWAI TATTOOS factsanddetails.com

MINANGKABAU PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELIGION, CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

MINANGKABAU: THE WORLD’S LARGEST MATRIARCHAL SOCIETY factsanddetails.com

MINANGKABAU LIFE AND CULTURE: HOUSES, FOOD, CRAFTS, SPORTS factsanddetails.com

BUKITTINGGI AREA OF WEST SUMATRA: MINANGKABAU AND WORLD'S LARGEST FLOWER factsanddetails.com

Ethnic Groups in Southern Sumatra

Ogan-Besemah are one of the primary ethnolinguistic groups in southern Sumatra. They are a diverse group of Muslim people with strong Sufi traditions. They usually identify themselves as Ogan (also known as Dempo) who live mostly in east and the Besamah (also known as the Pasemah) who live mostly in the west. According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Besemen population in the 2020s was 764,000. Their main language is the Pasemah dialect of Central Malay. About 98.5 percent are Muslims. The Ogan population at the same time was 179,000. Their main language is the Ogan dialect of Central Malay. About 99.7 percent are Muslims. Besemah districts in the west were converted to Islamic only in the latter part of the 19th century. Megalithic shrines on the Besemah plateau continue to be objects of vows and dedications. Much of the later work of conversion was carried out by the Nagshbandiyya Sufi order. [Source: John R. Bowen, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993); Joshua Project]

Most Ogan-Besemah live in villages made up of single-story wooden houses with metal roofs. In some places villagers spend much of the year living is shelters set up neat the fields to protect them. Rice is the primary consumption crop. Coffee and runner are primary cash crops. There are two primary kinds of marriage: 1) “belaki”, which involves the payment of a bride price and the residence of the couple with the groom’s family and association of the children of the marriage with the groom’s family. 2) “Ambig anag” involves no payment of a bride price and involves the couple moving in with the bride’s family and all children being linked to them. ~

Most children attend state schools. Boys are expected to receive some kind of religious training and undergo circumcision. Religion is often organized by village leader and the veneration of English remains in places where they found. Many religious gathering involve Sufi chanting. Similar chanting goes on at the feast that follow funerals and other important events. It is believed that chants generate merit that will be returned to the villagers in the form of blessings. ~

Komering inhabit the Komering River in South Sumatra province not far from the Ogan-Besemah. There are around 530,000 of them and most are Muslims. Their language, Komering, is a Lampungic language. Many live in stilt houses about one meter off the ground. Komering's typical food is Sambal Jok-jok, this chili sauce is made from grilled shrimp paste, chilies, sugar, salt, tamarind and orange juice. This chili sauce is usually eaten with grilled fish, fresh vegetables and warm rice. [Source: Wikipedia]

Kerintji live in the “Kerintji Basin,” two degrees south of the equator in West Sumatra. Also known as Corinchee, Corinchi. Corinchia, Kerinchi, Kinchai, Koerintiji, Korinchi, Korintji, Kurintji, they have traditionally lived in longhouses, fished from Lake Kerintji and raised irrigated rice. They are mostly Muslim and hold hereditary chiefs in high regard. Their pre-Islamic religion contained elements of ancestor worship, animism and Indic pantheism.

Lampung

The Lampung are an ethnic group native to Lampung and some parts of South Sumatra as well as in the southwest coast of Banten in West Java. Also known as the Jamma Lampung, Ulun Lappung, Orang Lampung or Lampungese, they speak the Lampung language and number around 1.5 million speakers with around 1 million in Lampung, 93,000 in West Java, 70,000 in Banten, 45,000 in Jakarta and 45,000 in South Sumatra. [Source: Wikipedia]

The origins of the Lampung people are closely linked to the history of the region known as Lampung. As early as the 7th century, Chinese sources referred to a southern place called Nampang, believed to have been associated with the Tolang Pohwang kingdom. The former territory of this kingdom is thought to correspond to present-day Tulang Bawang Regency or areas along the Tulang Bawang River, a view supported by Professor Gabriel Ferrand (1918). Historical evidence also suggests that Lampung formed part of the Srivijaya Empire, centered in Jambi, which expanded across much of Southeast Asia and controlled Lampung until about the 11th century.

Earlier records from the 5th-century Taiping Huanyu Ji chronicle list states in the Nan-hai (Southern Ocean) region, including two mentioned consecutively: To-lang and Po-hwang. While To-lang appears only once, Po-hwang is recorded repeatedly and is noted for sending envoys to China in 442, 449, 451, 459, 464, and 466. On this basis, some scholars have proposed the existence of a Tulang Bawang kingdom, although this interpretation largely derives from combining the two names found in the Chinese texts.

The Lampung language is spoken by the Lampung people in Lampung, southern Palembang, and along the western coast of Banten. It belongs to a distinct branch of the western Malayo-Polynesian family, known as the Lampungic languages, and is most closely related to Malay, Sundanese, and Javanese. The language has two principal dialects: Api and Nyo.

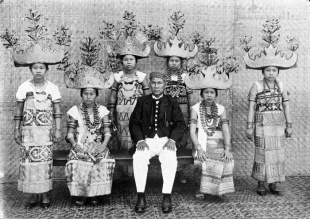

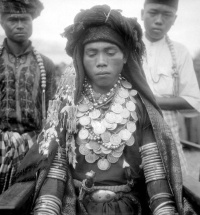

Traditionally, the ancestry of the Lampung people is traced to the Sekala Brak kingdom. Over time, Lampung society developed into two main cultural groups: the Saibatin Lampungs, who inhabit coastal areas, and the Pepadun Lampungs, who live primarily in the interior. Saibatin customs emphasize aristocratic traditions, whereas the Pepadun, who emerged later, developed social practices with more democratic values, in contrast to the aristocratic orientation of the Saibatin.

Tampan — Lampung Ceremonial Textiles

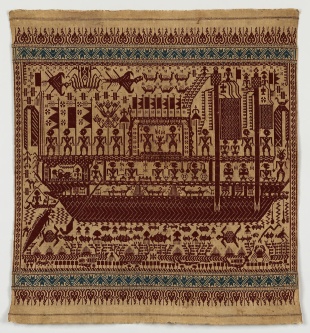

Situated along the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra—a vital trade corridor since antiquity—the Lampung region of southern Sumatra has long served as a meeting ground for diverse cultures and artistic traditions. The region’s rich textile heritage reflects the prosperity generated by the pepper trade, which flourished in Lampung for centuries. Drawing on this wealth, Lampung women created an impressive range of textiles, including ceremonial cloths as well as everyday garments. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Among the most visually striking of these textiles are tampan, small, square-woven cloths exchanged during important rites of passage. Nearly every Lampung family owned tampan, which were used to sanctify ritual occasions and to accompany individuals through the ceremonies marking the stages of life. They appeared at births and funerals, marriages and circumcisions, and at rituals associated with changes in social rank. Tampan were displayed during ceremonial meals, used as seating for elders who presided over customary law, and tied to the ridge poles of newly constructed houses. In this way, they functioned as a sacred medium binding the community together.

Tampan exist in two regional styles and two principal colors. Cloths woven in blue are associated with the secular realm, while those in red symbolize the sacred. Examples from the inland highlands feature stylized representations of natural or domestic subjects alongside geometric patterns, whereas coastal examples, known as tampan pasisir, are distinguished by elaborate depictions of ships and other detailed motifs. Although tampan were used across all social strata, the most ornate coastal pieces were reserved for the nobility.

Imagary on Wedding Tampans

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a 19th century tampan from Piya, Wai Ratai, Lampung Bay, Pasisir that is made of cotton and measures(79 x 73 centimeters (31 x 28 inches). Eric Kjellgren wrote: Tampon were an indispensable element of ceremonial life, displayed and exchanged as part of all major rites of passage, from rituals marking the birth and naming of a child to funerals, at which they served as a ritual pillow for the head of the deceased.' They were, and in some cases remain, an essential item in Lampung marriage ceremonies. . [Source:Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Wedding ceremonies today often include only a single tampon, but in the past, for marriages between wealthy families, more than one hundred tampon might form part of the ceremonial gifts presented by the family of the groom to the family of the bride. During the ceremony tampon also served to wrap specially prepared food, and among the Serawai subgroup, a tampon also formed part of the symbolic "tree of life," which was ritually destroyed at the conclusion of the ceremony.

Tampon were woven and used by both aristocratic and ordinary families, but the ornate examples produced by pasisir weavers (tampon pasisir) were a sumptuous prerogative of the nobility. Rich in pepper and lying along the Sunda Strait, a crucial trade route since antiquity, Lampung has long been a crossroads of cultures, and richly layered artistic influences are evident in the region's art. In their form, composition, and technique, tampon are similar to textiles produced by some Buddhist, or formerly Buddhist, peoples in Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and southern China.

The lndianized imagery of the tampon pasisir probably reflects the influence of the art of the Buddhist Srivijaya empire (ca. A. D. 650- 1400), which flourished just north of Lampung, as well as the kingdoms of the island of Java, immediately to the east. Rigged with sails of joined mats and steered with exterior rudders, which are distinctive to Indonesian and south Asian vessels, the fanciful ships that adorn the tampon pasisir may recall the features of the huge trading ships that plied the seas in precolonial times.

Depicted in cross section, with all their internal features visible, many of the ships are virtual floating palaces. In the present work a single figure, evidently a person of importance, lies in a cabin at the left, accompanied by an attendant. In the central cabin, a group of musicians play gongs and other instruments similar to those of a Javanese gamelan orchestra. A group of men with kris (ceremonial daggers) stuck into their belts appear to stand guard on deck. A multitude of banners wave from the vessel, and the skies overhead are filled with fantastic, birdlike creatures. The sea, too, abounds with life, including fish, octopuses, sea turtles, a crab, and a strange reptilian creature, possibly a crocodile, which appears poised to surface beneath a smaller boat, towed behind the main vessel. Replete with images of abundance and regal ease, the tampon reflects an idealized world of opulence, beauty, and fecundity to which its noble owner likely aspired.

Tapis — Lampung Ceremonial Skirts

Tapis are Lampung women’s ceremonial skirts. One in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection dates to 18th century or earlier. Made of cotton and silk, it measures 132 x 132 centimeters (52 x 52 inches) Kjellgren wrote: Opulent symbols of wealth and power, the lavishly embroidered women 's skirts, or tapis, of the Lampung region of Sumatra reflect the riches brought to the region through trade. Worn only by aristocratic women, tapis were flamboyant elements of ceremonial attire, possession of which marked the wearer as a woman of importance. [Source: “Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The ornate skirts were particularly associated with marriages, where they added to the splendor of the prodigious quantities of ceremonial textiles that were worn and displayed at aristocratic weddings, which, for the wealthiest, might last three or four days. 2 When not in use, the skirts were carefully preserved and often passed down within noble families as treasured heirlooms.

Tapis were worn as tubular garments: the ends of the textile (the right and left edges of the present work) were sewn together to create a cylindrical skirt, which the woman stepped into and drew upward around her body, securing it at the waist. The seam of the present example has been opened, making it possible to view the design in its entirety. There are several types of tapis, which occur in both brown and red palettes.

The brown variety, of which this work is among the finest examples, presents a study in textural and compositional contrasts. The backgrounds consist of subtle dark brown cotton cloth adorned with lacelike ikat designs in white, the natural color of the undyed thread. This soft, muted background is offset by two broad bands of lustrous silk embroidery with vigorous curvilinear designs that stand out boldly from the somber tones of the surrounding fabric. The significance of the enigmatic amoeba-like forms that dominate the silk embroidery is uncertain. However, the motifs may represent highly stylized human images. Some, as here, have smaller anthropomorphic images within them, perhaps symbolic of unborn generations. These images, together with the foliage-like forms that appear to sprout from them, suggest associations with fecun dity and the perpetuation of life.

Orang Rimba (Kubu)

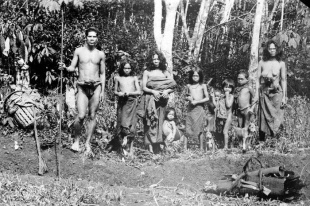

The Orang Rimba have traditionally been animist forest peoples who inhabit the lowland rainforests of southeastern Sumatra, mainly in Jambi Province. Also known as the Koeboe, Orang Darat, Kubu, Orang Batin Sembilan and Anak Dalam, they are largely former hunter-gatherers that embrace a number of distinct groups. They are believed to be related to the forest people of Sri. Lanka. Few even knew of their existence until the Dutch came in contact with them in the 19th century. In 1935 there were 25,000 of them. It is believed that there are less of them now. An estimated 2,500 Orang Rimba continue to practice their traditional ways. Most are settled. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Orang Rimba traditionally lived in small, nomadic groups. In their traditional society there were no class distinctions, only divisions based on age. No one acquired wealth or possessions and the forest was maintained in such a way as to ensure the maximum food supplies for all members of the group. Kubu were able to resist efforts by the government to settle them until the forest areas that they lived in were dramatically reduced by transmigration programs and palm oil plantations. The last remaining nomads have been forced to live in a 287-square-kilometer forest reserve. ~

Orang Rimba speak various Kubu languages that belong to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. These language are best understood as closely related languages or dialects of Malay spoken in the upstream regions of South Sumatra and Jambi, and are ultimately related to Malay. The lifestyle of the forest-dwelling Orang Rimba was portrayed in the Indonesian film Sokola Rimba (2013), which brought wider public attention to their way of life.

Two Kinds of Orang Rimba

Following Malay classifications, early European observers divided the Kubu into two broad categories: “tame” or “civilized” Kubu, who practiced swidden agriculture and maintained closer ties with settled communities, and “wild” Kubu, who lived deeper in the forest and made concerted efforts to avoid sustained contact with the outside world. Although closely related to Malay-speaking populations, these groups constitute distinct cultural traditions with differing economic practices and socio-religious systems. [Source: Wikipedia]

Orang Batin Sembilan refer to the “civilized” Kubu. The form the larger population and are swidden-based cultivators living in the central and eastern lowland forests of South Sumatra (approximately 35,000 people) and Jambi (about 10,000). As with other forest-oriented societies in the region, swidden fields serve as base camps from which families range into surrounding forests to hunt, gather, and collect forest products for trade.

Orang Rimba —literally “people of the forest” — are a much smaller population, numbering roughly 3,000, living primarily in the upstream regions of Jambi and South Sumatra. Their subsistence economy is highly flexible, alternating between swidden cultivation and a more nomadic lifestyle centered on foraging, especially the digging of wild yams. These activities are combined with hunting, trapping, fishing, and the collection of forest products for trade. In recent decades, forest product gathering has increasingly been supplemented—or replaced—by part-time rubber tapping and participation in logging.

Orang Rimba social life is organized around small, shifting camps. Some camps may consist of a single nuclear family during periods of intensive foraging, while others include extended families or multiple related households during swidden cultivation. Social relations are strongly egalitarian, with authority deriving primarily from age, gender, and knowledge of customary law and religious traditions rather than formal hierarchy.

Impact of Deforestation and Islamization on the Orang Rimba

Since the 1970s, the Orang Rimba have faced increasing displacement as a result of logging operations, the expansion of palm oil plantations, and government-sponsored transmigration settlement programs. Between 2000 and 2018, Indonesia has lost about 15 percent of its tree cover; in Jambi, losses reached 32 percent according to Global Forest Watch. Although President Joko Widodo announced a moratorium on new palm oil plantations, forest loss has already severed the ecological and spiritual foundations of Orang Rimba life. On top of this Orang Rimba communities have often been subjected to pressure or coercion to adopt Islam by groups like the Islamic Defenders Front, a professed morality force that dresses in white robes and has raided nightclubs and other places deemed un-Islamic. They have engaged in mass conversions of forest people and visit villages settled Orang Rimba to remind them to pray five times a day. . According to the New York Times only about 1,000 Orang Rimba families remain in the rainforest. Temenggung Tarip, a traditional healer who once invoked forest gods with offerings of flowers, says the rituals failed as logging and palm oil plantations destroyed sacred land. Outside the forest, many—Tarip included—converted to Islam, in part because Indonesian identity cards require affiliation with one of six recognized religions. Missionaries and local officials promoted conversion, while traditional animist practices were marginalized. [Source: Hannah Beech, New York Times, October 14, 2018]

Now living in a concrete house far from the jungle, Tarip farms rubber and oil palm on customary land, even as he recognizes these crops helped destroy his former way of life. Hannah Beech wrote in the New York Times, “Tarip lives with his wife, Putri Tija Sanggul, in a concrete shell in Sarolangun, a three-day walk from the wilderness that used to be their home. The only reminder of nature in their new house is a bunch of purple orchids that cascades down a wall. The flowers are plastic. Missionaries, both Muslim and Christian, have tried to ease the transition to what the Orang Rimba call “the outside.” Beyond the obvious differences — concrete walls, processed food, brightly colored plastic — the outside is confounding in other ways. The forest was cool, sunlight barely penetrating the dense foliage. Concrete, by contrast, holds the heat. Sleeping in the stuffy confines of his home is something to which Mr. Tarip is still not accustomed.

Ms. Sanggul, Mr. Tarip’s wife, often claws at the veil around her head and hitches up her dress to air her legs. She is a princess of her Orang Rimba tribe, and her noble lineage meant she could conjure the forest spirits with ease until one day, she said, she couldn’t. “The gods took away my gift,” Ms. Sanggul said. “Nevertheless, Mr. Tarip still respects indigenous traditions. Four of his daughters and three of his sons remain in the jungle, and he knows that by visiting them he could compromise their communion with nature. The list of Orang Rimba taboos is long and includes soap, fried chicken and certain clothes like the Muslim prayer cap Mr. Tarip now wears. Perfume is also prohibited.

Gayo

The Gayo live predominately in the central highlands of Aceh Province in northwest Sumatra. Also known as the Gajo, Utang Gayo, they have traditionally been rice farmers and traders and have been Muslims since the 17th century. They number about 350,000, double their number in 1980, with about half them being Gayo speakers. They have traditionally had a strong ethic identity but have been under nominal Aceh suzerainty.

Substantial written references to the Gayo people appear only in the late nineteenth century, but their history in the central highlands of northern Sumatra is much older. By the seventeenth century, the Gayo homeland was likely under the influence of the Islamic kingdom of Aceh, and the process of Islamization had already begun. After Dutch forces penetrated the highlands in 1904, some Gayo continued to resist colonial rule. Under the Dutch they developed coffee agriculture as cash crop and achieved high levels of education and were involved in the Islamic modernism and Indonesian nationalist movements, participated in the massacres of 1965 and 1966 and were loyal Suharto and Golkar allies. [Source: John R. Bowen, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Gayo have a reputation for being fairly serious Muslims. In the 1920s, there was a movement to rid the religion of animist practices. Even so such beliefs persist in some rural areas. Most religious practices are in line with those of traditional Islam. Important life cycle events include a ritual bath, introduction to the spirit world and naming ceremony seven days after birth, circumcision for boys and girls. In the arts, there is a long tradition if songs, poetry and ritual chanting, often with individuals or teams competing against one another. ~

Gayo Life and Society

In the old days many Gayo lived in longhouses but few of them do anymore. Most of the Gayo that remain in villages live in single family dwellings with palm leaf of corrugated iron roofs. Most farmers raise rice to eat in paddies with water buffalo and grow coffee as a cash crop. Households may consist of nuclear families or extended families, with adolescent boys living in the village prayer house. [Source: John R. Bowen, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Gayo society is divided into two kinds of groups: 1) intra-villages kin categories associated with different village offices; and 2) inter village kin categories associated with linkages to common villages somewhere else. Descent in both systems may be traced through either males or females, although claims of patrifilial descent carry particular weight in village politics. Both village and supravillage kin groups are exogamous. Marriages are generally between people no more closely related than third cousins and may or may not involve an exchange of goods. The ceremony involves a ritual exchange goods and speeches. ~

Before colonial rule, Gayo villages consisted of one or more longhouses built on stilts, each divided into kitchens and sleeping areas shared by three to nine nuclear or extended families. These houses were often clustered together, frequently on hilltops, for defense. Beginning in the 1920s, longhouses were gradually replaced by low, single-family dwellings, though some survived in southern Gayo areas into the 1980s.

Saman Dance

The Saman dance is part of the cultural heritage of the Gayo people of Aceh province in Sumatra. Boys and young men perform the Saman sitting on their heels or kneeling in tight rows. Each wears a black costume embroidered with colourful Gayo motifs symbolizing nature and noble values. The leader sits in the middle of the row and leads the singing of verses, mostly in the Gayo language. These offer guidance and can be religious, romantic or humorous in tone. Dancers clap their hands, slap their chests, thighs and the ground, click their fingers, and sway and twist their bodies and heads in time with the shifting rhythm – in unison or alternating with the moves of opposing dancers. These movements symbolize the daily lives of the Gayo people and their natural environment. [Source: UNESCO]

The Saman is performed to celebrate national and religious holidays, cementing relationships between village groups who invite each other for performances. The frequency of Saman performances and its transmission are decreasing, however. Many leaders with knowledge of the Saman are now elderly and without successors. Other forms of entertainment and new games are replacing informal transmission, and many young people now emigrate to further their education. Lack of funds is also a constraint, as Saman costumes and performances involve considerable expense.

Saman dance was inscribed in 2011 on the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding. Involving a community of not only players and trainers but also enthusiasts, prominent religious leaders, customary leaders, teachers and government officials, Saman dance promotes friendship, fraternity and goodwill and strengthens awareness of the historical continuity of the Gayo people; Saman dance faces weakening informal and formal modes of transmission due to reduced opportunities for performance and the disappearance of the cultural spaces where transmission takes place, associated with social, economic and political changes that include penetration of mass media and the rural-urban migration of the younger generations; knowledge of the element is diminishing and commercial activities are increasing, posing a threat to the continued meaning of Saman dance to its community. Many important documentation on the Saman dance were destroyed in the 2004 tsunami. An educational program has been proposed to revitalize traditional modes of transmission of the Saman dance in the mersah dormitories for young men.

Puteh: the White Tribe of Sumatra

The Puteh are a group of white-skinned people that has traditionally lived along a beautiful stretch of tropical coastline of coves and jungle in western Sumatra, about three hours south of Banda Aceh, that was devastated by the 2004 tsunami. They are believed to be descendants of shipwrecked European sailors, possibly from Portugal, who had merged into the culture of Aceh over the generations but maintained their striking Western looks. The Puteh are Muslims who speak a local Acehnese dialect Puteh. Before the 2004 tsunami there were about 500 of them. [Source: Nick Meo, The Times, June 28, 2005 ^, BBC]

Nick Meo wrote in The Times,“The Putehs — the name means white in Acehnese dialect — lived in fishing communities at the edge of the ocean. Nobody is quite sure how the Putehs originally arrived in the East Indies, but local legend has it that their descendants were shipwrecked sailors who converted to Islam and married local women. They had no European words in their dialect. The men were fishermen, poor by Indonesian standards, but the Puteh women enjoyed famously exotic looks. Their dark skins and blue eyes made them prized as brides by would-be husbands from the regional capital Banda and from as far away as Jakarta. The legends hold that the Portuguese ships, which were shipwrecked, were filled with gold as well as carrying the Putehs' forefathers. Coins would occasionally wash up from wrecks after storms. “^

There is some historical evidence upporting a partially Turkish origin for the Putehs. Turks and the people of Aceh are linked historically. The Sultan of Aceh, Alaaddin Riayat asked for help from the Ottoman Sultan Süleyman regarding the Portuguese invasion and the activities of missionaries in Sumatra. An envoy of 26 Turkish galleons set sail, but were attacked by the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean. Only two ships returned to Istanbul. The successor of Sultan Süleyman, Selim II, issued a decree and sent 15 galleys and 2 escort ships to Aceh. The Ottoman government did not only send ammunition, weapons and soldiers to the Muslims in Aceh but also military instructors, housing and construction specialists, experts on metals-weapons and scholars. When Ottoman sailors arrived in Aceh, the Portuguese declared that they would not fight and handed over the city. Selim the II allowed those who wished to stay in Aceh. The people of Aceh loved the Ottomans so much that they added a crescent and star on their flags. There were reports of a Turkish cemetery in which Ottoman sailors were buried but nothing was left after the 2004 tsunami. [Source: thephora.net/forum, turkishtime.org]

Puteh All But Wiped Out by the 2004 Tsunami

Nick Meo wrote in The Times, “Before December 26 there were more than 50 families of Putehs. Now there is one man left. The Putehs lived in fishing communities at the edge of the ocean which suffered the worst destruction from the tsunami. Nearly all died and their villages were wiped from the face of the earth. The sole surving man from his tribe is Jallaluddin Puteh, a 42-year-old fisherman, who, together with his wife, lived because their home was at the landward side of the village and they had a head start running towards higher ground when the wave struck. [Source: Nick Meo, The Times, June 28, 2005 ^]

“Mr Puteh believes that all of his extended family who lived around the town of Lamno on the west coast of Sumatra died in the disaster — about 500 souls in six villages. His immediate family, and a handful of women who had married and moved to the capital Jakarta, are probably all that is left of one of Indonesia’s most unusual communities. "I just don’t know why God spared me and my wife although I have thought long about it," said Mr Puteh. Two of their children died in the wave, although two others, boys who were at school in the capital Banda Aceh, survived. Mr Puteh was washed about a mile by the force of the wave and dumped on a hill. His wife was washed up on another hill. Of the 1,300 inhabitants of the six villages the Putehs shared with dark-skinned Indonesians, only around a dozen people survived in total. His village is now under water. ^

“Mr Puteh admitted that the past few months have left him defeated. He said: "I have lost nearly all my friends and family. It is still hard to believe they are all dead and I am the only one left." Now he lives in a tent subsisting off food handouts. A few others in the town with some Portuguese blood survived the wave because they lived inland. The grandfather of Nur Hayat, a 25-year-old woman, was a Puteh. She said: "I lost uncountable relatives. It is so sad, they were such beautiful people. Their culture was 100 per cent Acehnese, they had the same religion, spoke in the same dialect, sang the same songs. The only difference was their looks. Men from Banda Aceh and Jakarta seeking wives would go there. The blue-eyed women were famous as the most beautiful in Indonesia." ^

“Campong Baro, one of the villages where Putehs lived, is now a muddy wasteland with the metal skeleton of a bridge lying amid the stumps of coconut palms where the tsunami washed it. The handful of surviving fishermen find it hard to motivate themselves. Salahin, a 32-year-old fisherman from the village, said: "I would like to marry again but I have no money. "It is hard to work now. Before it happened, when I came back tired there would be my wife waiting and my children to play with. But they are gone." Jamalludin Puteh said that he could not get his life back to any kind of normality, partly because most of the big fishing boats were destroyed in the disaster and there are not enough crews left to get the industry going again. "I am unemployed with nothing to do except think about what happened to us," he says. “I feel like our future was destroyed by the wave.” ^

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025