BATAK SOCIETY

Batak societies and villages revolve around descendants of the village founder, who sort of play the role of aristocrats, and lineage mates in the form of wife givers (who have provided the descendants of the founders with wives and blessing for many generations) and traditional wife receivers (who marry the founder’s descendant’s daughters and provide the village with various services in return). Batak villages are ruled by a council of elders, chiefs (known as rajas), and chiefs councils in accordance with genealogical positions in founder’s lineage. They preside over ceremonies, preside over some judicial matters and are expected to set high moral standards for others to follow. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

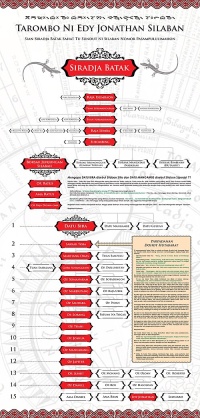

Batak society is organized around patrilineal descent, with individuals belonging to clans that trace their ancestry through the male line. Among the Toba Batak, these clans are known as marga, while among the Karo they are called merga. Both are numerous and further divided into subclans. A Toba marga is named after a founding ancestor whose lineage can be traced back twenty or more generations through detailed genealogies (tarombo). In contrast, a Karo merga bears a collective name not tied to a specific ancestor, and genealogies are not formally maintained.

Unlike the Balinese, who have several different traditional group affiliations at once, or the Javanese, who affiliate with their village or neighborhood, the Batak traditionally orient themselves primarily to the marga, a landowning patrilineal descent group. Traditionally, each marga is a wife-giving and wife-taking unit. Whereas a young man takes a wife from his mother’s clan (men must seek wives outside their own marga), a young woman marries into a clan within which her paternal aunts live. [Source: Library of Congress]

The marga has proved to be a flexible social unit in contemporary Indonesian society. Batak who resettle in urban areas, such as Medan or Jakarta, draw on marga affiliations for financial support and political alliances. While many of the corporate aspects of the marga have undergone major changes, Batak migrants to other areas of Indonesia retain pride in their ethnic identity. Batak have shown themselves to be creative in drawing on modern media to codify, express, and preserve their “traditional” adat. Anthropologist Susan Rodgers has shown how audiotaped cassette dramas with some soap-opera elements circulated widely in the 1980s and 1990s in the Batak region to dramatize the moral and cultural dilemmas of one’s kinship obligations in a rapidly changing world. In addition, Batak have been prodigious producers of written handbooks designed to show young, urbanized, and secular lineage members how to navigate the complexities of their marriage and funeral customs.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BATAKS: GROUPS, HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND WERE THEY REALLY CANNIBALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK RELIGION: CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, BURIALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK LIFE: HOUSES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK factsanddetails.com

BATAK CULTURE: MUSIC, ART, FOLKLORE, CRAFTS AND LIFE-SIZE PUPPETS factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SUMATRA factsanddetails.com

SUMATRA: HISTORY, EARLY HUMANS, GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE factsanddetails.com

LAKE TOBA AREA: BATAKS, SAMOSIR ISLAND AND THE TOBA SUPERVOLCANO ERUPTION 71,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

Batak Customs and Etiquette

Social interaction placed great emphasis on respect, especially toward elders and strangers. Polite speech was essential, and refusals were commonly softened with apologetic phrases, such as sattabi in Toba or ula ukurndu litik in Karo. Greetings, expressions of thanks, and farewells often involved touching hands, reinforcing social harmony and courtesy. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Courtship followed culturally accepted forms. Among the Toba, young men and women could meet through martandang, an evening visit in which young men came to the house of unmarried women under the supervision of a widow. Conversation took place through riddles, preserving modesty and restraint. If a young man became interested in a woman, he formally approached her parents to propose marriage. Among the Mandailing, courtship could occur through markusip, in which a young man secretly entered the space beneath a woman’s stilt house and signaled his presence so the two could whisper to each other through the floorboards.

The expression in the Toba Batak language — Jonok dongan partubu jonokan do dongan parhundul — means one must always maintain good relations with his neighbors, because they're the closest friends. However, in the implementation of custom, one first looks to his clan, although basically neighbors should not be overlooked. [Source: ibdo.blogspot.jp]

Batak Family and Kinship

The most important social unit is the extended family group descended from a common grandfather and living together in one settlement. Among the Toba this unit is called saompu, and among the Karo sada nini. Within it are several nuclear households—ripe in Toba and jabu in Karo—each consisting of a married couple, their unmarried children, and their married sons. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Marriage follows strict kinship rules. The ideal, though now uncommon, marriage is between a man and his mother’s brother’s daughter. Marriages between members of the same marga or between a man and his father’s sister’s daughter are forbidden. Marriage alliances form long-standing exchange relationships between kin groups: one group consistently gives wives to another, which in turn gives wives to a third, creating a circular pattern of exchange.

A husband is expected to show deep respect toward his wife’s family, whom he regards as dibata ni idah, or “gods on earth.” Polygyny was traditionally limited to wealthy men and even then was uncommon; in some cases a second wife remained living with her parents and was only visited by the husband, a practice not accepted among Christians.

Divorce may occur for several reasons, including childlessness, adultery, or a wife’s inability to get along with even one member of her husband’s kin. Among the Karo, divorce cases are decided by the raja urung or a village council and usually require the return of the bride-price to the husband’s family. A Karo woman may also enter a form of temporary separation (ngelandih) by returning to her parents’ home after a serious dispute.

Batak Marriage Customs

Among ordinary Batak marriage and clan alliances are very important. Groups are organized along these lines and have traditionally done field work together. Marriages often take place on a wife giver, wife taker basis between two lineages to form an alliance, often with one lineage being dominate over the other. To maintain the alliance ideally a man marries his mother’s brother’s daughter to fulfill an obligation began by his father. The marriage is often accompanied by elaborate exchanges of gifts such as textiles, livestock and jewelry. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

A marriage not only links two individuals, but also joins two kin groups, often reaffirming longstanding relations. The man's family sends a delegation to propose to the woman's family. If the woman's family accepts the proposal, the two families hold a discussion to negotiate the bride price, as well as the gifts that the man's family will give to the woman's relatives. They also set the wedding date. Among Christianized Toba, it is important for the families to formally announce the wedding to the church congregation. The wedding feast is attended by relatives of both families and all the villagers. The celebration includes handing over the bride price, slaughtering a water buffalo or several pigs, and distributing the meat to relatives." [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Should any of the relatives object to the wedding, the couple may elope. The man will take the woman to his parents' house. Within a day, the groom's family must send a delegation to inform the bride's family of the elopement and the groom's intention to marry the bride. After some time, the groom's family formally asks the bride's family for forgiveness in a ceremony. Afterwards, a traditional wedding can take place. ^

Couples often live with the father’s family for a couple of years before establishing a household of their own. Divorce is frowned upon because it jeopardizes alliances. Household structures are filled with people coming and going from the villages to the cities. Rice fields, the most valued property, is handed down from father to son and sometimes given as a bridal gift. ~

Karo Batak Wedding

A Karo Batak wedding is a complex, highly symbolic life-cycle ceremony that affirms marriage not only between two individuals but between extended families and clans (marga). The Karo Batak are one of several Batak peoples whose homelands lie in the highlands of North Sumatra, particularly north and east of Lake Toba. While Batak groups share broad cultural features, each has distinct customs, languages, and ritual practices. Among the Karo, weddings are among the most elaborate expressions of adat (customary law). [Source: Danielle Surkatty, Kem Chicks' World, September 2001.expat.or.id]

Central to a Karo Batak marriage is the marga system, an extensive network of patrilineal clans that regulates social identity and marriage rules. Ideally, a Karo Batak marries another Batak, but never someone from the same clan. When a non-Batak groom is involved, he may be ritually adopted into a Karo clan through a formal ceremony, thereby gaining a clan identity and the right to marry according to adat. This adoption is not symbolic alone: it creates lasting social obligations and relationships, though inheritance rights are usually excluded.

Clan representatives—sembuyak (clan mates), kalimbubu (wife-givers), puang kalimbubu (senior wife-givers), and anak beru (wife-takers)—must all agree to the adoption and marriage. Discussions are traditionally led by male elders, reflecting the importance of lineage and political balance within and between clans.

Before the wedding itself, two important ceremonies are held to formally request the bride’s hand. The first, ngembah belo selambar (“bringing a betel leaf”), opens negotiations between the families. Gifts of kampil—woven baskets containing betel ingredients, tobacco, and small foods—are exchanged to create a relaxed atmosphere for discussion. Matters such as bridewealth (tukor), guest numbers, costs, and responsibilities are settled at this stage. [Source: Danielle Surkatty, Kem Chicks' World, September 2001.expat.or.id]

This is followed by nganting manuk (“bringing a chicken”), a ceremony symbolizing agreement on the bridewealth. Traditionally, a chicken is brought to the bride’s family; today this is often accompanied by a communal meal. The bridewealth is standardized within each clan and represents compensation for the bride’s transfer from her natal clan to her husband’s.

Karo Batak Wedding Ceremony, Dress and Celebration

The main wedding feast, known as kerja si mbelin (“the great work” or big party), is a vibrant public celebration. Guests sit on woven mats rather than chairs, emphasizing equality and communal participation. The bride and groom enter in a long procession with their families, accompanied by ritual gestures symbolizing fertility and prosperity. [Source: Danielle Surkatty, Kem Chicks' World, September 2001.expat.or.id]

A distinctive feature of the ceremony is the landek dance, performed by the couple and their families. Once the bridewealth is formally paid and accepted, the couple is considered married under Batak custom. As the bride and groom dance and sing, relatives and guests may step forward to place money or gifts before them—a modern addition that complements, but does not replace, traditional obligations. Speeches follow in a prescribed order, delivered by representatives of each kin group. These speeches offer advice on married life, relations with in-laws, and proper conduct within the clan system. Gift-giving accompanies these moments, reinforcing social bonds.

Karo Batak weddings require elaborate traditional dress. Brides wear a heavy headdress known as tudung gul, while grooms wear the bulang-bulang headcloth. Both are adorned with gold jewelry (emas sertali), often heirlooms lent by female relatives. Traditional textiles known collectively as uis nipis play a central role; different pieces are worn on the shoulders, hips, or waist, each with specific ritual meaning. [Source: Danielle Surkatty, Kem Chicks' World, September 2001.expat.or.id]

Textiles are also presented as gifts and ceremonially wrapped around the couple, symbolizing unity, fertility, and the hope for descendants. Another important gift is luah berebere, household items given by the bride’s maternal relatives to help establish the new home. These usually include bedding, utensils, rice, and symbolic foods such as eggs and live hens, all representing continuity and abundance.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025