BATAK LIFE

The Batak grow wet rice were there is enough irrigation water and have built numerous terraces and raise dry rice where enough water is unavailable for wet rice. They also grow peppers, cabbage, tomatoes and beans and raise cash crops such as coffee, tobacco, fruits and cinnamon. In Lake Toba and other places the Batak practice fish farming. The government has encouraged them to practice fish farming and grow peanuts. Some traditional products such as camphor are still collected from the forest. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The Batak have a reputation for being one Indonesia’s most literate and educated peoples. They are found in significant numbers in Jakarta, Bandung, Surabaya and other large cities and have traditionally worked as civil servants, teachers, clerks and journalists. In 2005, the Batak region had a very high literacy rate by Indonesian national standards. The regency of Mandailing Natal had the lowest HDI in the Batak region, at 98.53, which was higher than Jakarta's rate of 98.32.

Human Development Index (HDI) levels in Batak regions vary considerably. Toba Samosir (74.5) and Karo (73.5) have higher HDI scores than North Sumatra as a whole (72), while Simalungun and Dairi fall slightly below, at 71.3 and 70.5 respectively. All of these exceed Indonesia’s national HDI of 69.6. Mandailing Natal is the exception, with an HDI of 68.8. Its GDP per capita is only US$3,677, compared with US$8,035 in Toba Samosir, and its infant mortality rate is 66.61 deaths per 1,000 live births, far higher than Karo’s 25.78 and the provincial average of 43.69. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

In 2002, the Gender-Related Development Indexes (GDIs) of the regencies in the Batak region, which combine measures of women's health, education, and income relative to men's, were all higher than Indonesia's national GDI of 59.2. The GDIs were 69.3 for Toba Samosir, 68.5 for Karo, 66.5 for Dairi, and 61.5 for Simalungun. Only Mandailing Natal was lower at 58.4, which was also lower than North Sumatra's GDI of 61.5. However, the Batak regencies' Gender Empowerment Measures (GEM), which reflect women's participation and power in political and economic life relative to men's, were all lower than the national GEM of 54.6. They ranged from 53.4 in Dairi to 46 in Karo. ^

RELATED ARTICLES:

BATAKS: GROUPS, HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND WERE THEY REALLY CANNIBALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK RELIGION: CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, BURIALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, KINSHIP factsanddetails.com

BATAK LIFE: HOUSES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK factsanddetails.com

BATAK CULTURE: MUSIC, ART, FOLKLORE, CRAFTS AND LIFE-SIZE PUPPETS factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SUMATRA factsanddetails.com

SUMATRA: HISTORY, EARLY HUMANS, GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE factsanddetails.com

LAKE TOBA AREA: BATAKS, SAMOSIR ISLAND AND THE TOBA SUPERVOLCANO ERUPTION 71,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

Batak Food

Batak food is known for its intense flavors from ingredients like ginger, turmeric, galangal, chili, and especially andaliman, which provides a unique citrusy-peppery kick. These characteristics are evident in dishes like Arsik (spiced carp), Saksang (pork/dog in spiced blood gravy), Babi Panggang Karo (grilled pork with blood sauce), and Mie Gomak (spicy noodles). Key ingredients include andaliman (Sichuan pepper), daun ubi tumbuk (mashed cassava or sweet potato leaves with spices), Sambal tuktuk (a fiery chili paste, often featuring andaliman). Tuak, palm wine, is a traditional drink often enjoyed with meals.

The Batak are fond of pork and also eat dog and congealed blood. Rice is the staple food and is supplemented by cassava, taro, maize, beans, and bananas. A popular side dish is bulung gadung tumbuk: pounded cassava leaves stewed like a curry. A popular feast food is saksan: roast pig served with a spicy, ginger-laden sauce that includes the animal's blood. Dengke ni ura dohot na margota is a large lake fish spiced with tamarind and kept for two or three nights before eating. Dengke ni arsik consists of carp and cassava leaves that are spiced and cooked until the fish is tender and dry. Pinadar is grilled chicken or pork mixed with hot spices, tamarind, and salt. Tuak tangkasan is a type of palm alcohol flavored with bark. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life, Cengage Learning, 2009]

Popular Dishes

Arsik is a signature fish dish (carp) cooked with turmeric, torch ginger, and andaliman pepper, giving it a unique sour and spicy taste.

Saksang is a rich stew of pork (or sometimes dog) simmered with spices, coconut milk, and its own blood.

Babi Panggang Karo (BPK) is Grilled pork, often served with a dipping sauce made from pork blood, and mashed cassava leaves.

Mie Gomak is a spicy noodle dish, sometimes called "Batak spaghetti," served in a broth or fried.

Dengke Mas na Niura is Raw carp marinated in spices, similar to ceviche but with distinct Batak flavors.

Manuk Napinadar is Grilled chicken with a spicy and aromatic sauce.

Dali ni Horbo is a A unique dish of buffalo milk curd, often cooked with spices.

Batak Clothes

Although elements of traditional dress are still visible in daily life, most Batak today dress much like other Indonesians, favoring international styles such as T-shirts and jeans or Malay-inspired kebaya blouses. Rectangular, intricately patterned cloths known as ulos among the Toba and uis among the Karo remain central to ceremonial occasions, worn as part of formal attire and exchanged as gifts to affirm social ties. An ulos may be folded into a broad headcloth, draped across the back as a shawl, worn over one shoulder as a sash, or used as a baby carrier. In the past, women sometimes wore the ulos as a sarong with the upper body exposed, or wrapped it around the entire body, leaving only the shoulders bare. Traditional attire also included jackets and vests. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

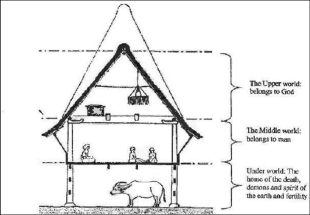

The colors of the ulos carried symbolic meaning: white represented the upper world and life, black the underworld and magical power, and red the middle world, bravery, and spiritual potency. Historically, the Karo favored indigo-dyed cloth, but today they tend to prefer dark red, reflecting Simalungun tastes. Toba weavers have long produced textiles in Karo styles for Karo consumers. In recent decades, machine-woven fabrics that imitate older handwoven designs have become popular, especially among younger people, who also increasingly request traditional patterns woven with gold or silver thread in the style of Malay songket.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The Toba Batak, who occupy the central part of the Batak region, are especially renowned for their handwoven textiles. Produced exclusively by women, these cloths serve both as clothing and as ritual gifts exchanged to mark social relationships. One important textile, the ulos ragidup, plays a central role in wedding ceremonies: on the wedding day, the bride’s father presents it to the groom’s mother, symbolizing the union of the two families and the hoped-for fertility of the couple. The cloth is then preserved as an heirloom and passed down through generations.

Batak Villages

The traditional Toba village (huta) consists of eight to ten houses arranged facing one another across a wide central avenue. This open space is used for drying rice and for ceremonial gatherings. All residents of a huta belong to the same clan. Community meetings are held in an open area (partukhoan) near the village gate. In contrast, the Karo kuta is much larger, accommodates families from different clans, and includes a formal meeting hall (balai kerapatan). [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Some Batak live in small villages with only four or five houses. Others live in large villages with 100 to 200 houses. Some traditional villages have Great Houses (carved high-peak aday houses, where several clan-related families) but these days these are far outnumbered by Malay-style houses with metal roofs. In the pre-colonial period, when warfare was common, Batak villages were heavily fortified, surrounded by high earthen walls or stone embankments, moats, and dense stands of bamboo.

The Batak people living on the Samosir islet in Lake Toba, located in the heart of North Sumatra, still maintain their traditional houses and settlement patterns. However, they no longer construct stone monuments. In the Batak highlands, traditional houses with distinctive, pointed roofs line the landscape. These houses are built on stilts so that the families' animals, such as pigs and buffalo, can live underneath. [Source: UNESCO]

In the early 1980s, there was a resurgence of interest in traditional house carving among urban Bataks, many of whom worked for the provincial and national governments. Several public works projects in towns and cities incorporated traditional Rumah Adat-style architecture, necessitating the production of large carved facades, which primarily adorned hotels and vacation homes in the Toba Batak region. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Batak Houses

Many Batak houses are built on stilts, up to two meters off the ground, and constructed of wood without nails using slots and twine. The roofs are made with sugar-palm leaves or corrugated metal. The gables often have carvings of horned lion heads, snakes, lizards or monsters with bulging eyes to protect the occupants from evil spirits. Animals are raised in the open space beneath the house. Rattan mats are often hung inside, giving the house a dark atmosphere.

As in other places, the number of traditional houses declined as people moved into simpler or more modern homes, following modern trends and pressures. Today, most Batak live in brick or cement houses, and corrugated metal roofing has largely replaced thatch, even on many traditional dwellings. Classic Batak houses are rectangular and raised on piles. A traditional Toba house shelters a single extended family: a married couple and their unmarried children, the eldest son and his family, and the father’s widowed sisters. The structure is distinguished by its steep saddle-shaped roof, whose ends extend far beyond the walls. At the front, the roof projects even farther to cover a veranda, beneath which the entrance staircase begins. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Karo houses are considerably larger, traditionally accommodating eight related families. Each family occupies about 5 square meters (approximately 54 square feet) of living space and shares a hearth with one other family. The apartments—now sometimes rented to unrelated families—are arranged four on each side of a central hall, which often includes a gutter running down the middle to collect debris. The house has identical doors and verandas at both the front and rear. A distinctive roof type used on square-plan houses features side slopes that rise directly to the ridgepole, while the front and back slopes stop short and connect to it with vertical walls. The most imposing structures were the rumah anjung-anjung of rajas, whose roofs were crowned with a miniature house.

Traditional Batak Houses

Traditional houses have thatch saddle-shaped roofs—that make the houses like as if they have horns—and timbers carved into graceful designs. The living quarters often is a large open space with no walls. Sometimes as many as a dozen families live in this area. Many have a distinctive trapdoor in the floor, large gable ends and buffalo horns.

An Indonesian author who grew up in the Toba Batak region in the early 20th century wrote: “Our house was a balebale, so we were obviously not rich. It was all black inside from the smoke...That is, no more than a hut on four poles. Its walls were made of beaten bamboo and its roof of paddy stalks (the floor was changed every year so it wouldn’t get holes in it). The other houses were called sopa and ruma, which were much larger and more beautiful; they were the houses of rich people. The ruma, for instance, had eight pillars. Its walls were made of carved wood planks and its roof was of black sugar palm fiber. These houses had a single room, in which people ate, slept, and received guests. The pillars were very tall, so that the space underneath the house could be used as a pen for livestock, which made it rather “fragrant.” [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

“There was also a new type of house, usually called an emper (verandah). Its structure resembled the sorts of houses we see in large numbers in the city today.The new houses were likely, at that time, bungalows introduced by the Dutch. The Batak include seven different regional groups, all of which cannot be discussed here. The elite homes of Batak also boast impressive saddleback roofs with outward leaning gables. Construction techniques resemble Minangkabau methods, using posts and beams fastened by pegs or notches and built atop piers.

The Batak largely converted to Protestantism in the nineteenth century, abandoning clan house rituals and instead building smaller, single family homes. The rumah gorga (carved house) is the most prestigious structure among the Toba Batak. Entered from beneath, these homes are exquisitely carved and painted with deities and mythical creatures. Carving on the exteriors is especially fine and difficult to carry out, using a mallet to tap a razor sharp carving knife. Most gorga work consists of three parallel grooves and requires master carvers.

Batak Work and Economic Activity

Most Batak make a living from agriculture. In some areas they cultivate irrigated rice, while elsewhere they grow maize, cassava, indigo, sugar palm, and other crops on dry fields, in part still using swidden (shifting cultivation) methods. Karo and Simalungun farmers specialize in vegetables and fruits for regional markets in Medan as well as for export to Singapore and Malaysia. Since the colonial period, large plantations—particularly in the Simalungun region—have produced rubber, oil palm, cacao, tea, and tobacco; these estates once relied heavily on Chinese and Javanese labor. Other important cash crops include coffee, especially among the Mandailing and Dairi, and cloves. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Agricultural labor is divided by gender: men clear and plow the land and construct irrigation systems, while women plant, weed, and harvest crops. Neighbors and close kin cooperate closely in farm work. Water buffalo are kept as draft animals and for sacrifice and consumption at ritual feasts, while pigs are raised for everyday meals as well as ceremonial occasions. Cattle, goats, chickens, and ducks are commonly raised for sale in coastal cities. Fishing is also a major occupation, particularly around Lake Toba.

Owing to relatively high levels of education, Batak are well represented in office work, including government administration, as well as in teaching and health services throughout Indonesia. They engage in a wide range of occupations, from operating small tire-repair workshops to serving as senior government officials.

Today, many Batak work as bus and taxi drivers, mechanics, engineers, musicians and singers, writers and journalists, teachers, economists, scientists, military officers, and lawyers. Although Batak make up a minority of Indonesia’s population—about 3.6 percent, or roughly 8–9 million people according to the 2010 census—they are disproportionately prominent in public life, particularly in the legal profession, where several Batak figures have achieved national recognition.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025