LAKE TOBA

Lake Toba (100 kilometers south of Medan) is about 80 kilometers (50 miles) long, 27 kilometers (16 miles) across, is 450 meters (1,400 feet) deep at its deepest point amd and covers 1,145 square kilometers (685 square miles). Fringed in most places by steep cliffs, the lake is a caldera left over from one of the largest volcanic explosions ever. The blast occurred 69,000 to 77,000 year ago, produced a caldera 100 kilometers long, and deposited a layer of ash and pumice 2000 feet to the north of the lake.

Lake Toba (Danai Toba) is the largest lake in Southeast Asia and, according to the Guinness Book of Records, the world's largest and deepest volcano crater. The lake is so big that an island almost the size of Singapore could fit inside it. It lies in a rugged mountainous area with dotted with fertile plains, rice paddies, coffee plantations, banana, mango, papaya and coconuts trees and forested and deforested mountains. The water is exceptionally clear. The mountains are often shrouded in mist.

Lake Toba at one time was one of the most popular tourist destinations in Indonesia and an ideal place to relax. But now it doesn’t receive as many tourists as it used to. Seven districts surround lake Toba, they are the districts of Simalungun, Toba Samosir, North Tapanuli, Humbang Hasundutan, Dairi, Karo, and Samosir. Among these, the island of Samosir is definitely the most favored destination for visitors. Twenty-seven kilometers (16 miles) from Kabanjahe, on the north side of the lake, is 360 foot Sipiso-piso waterfall which can be viewed from a gazebo on top of one of the hills near the town of Tongging. Some places receive eight feet of rain year.

Lake Toba sits at an elevation of 900 meters above sea level. The weather here is cool but pleasant, but if you’re used to hot temperatures remember to bring a jacket. Change all the money that you will need before you leave Medan as the exchange rate can be poor in the Toba area. If you are taking the bus between Medan and Parapat make sure you get on an express bus to avoid doubling your travel time.

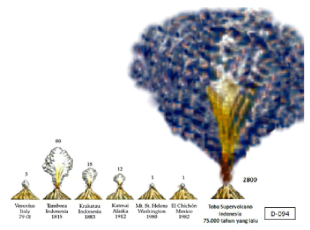

Toba Supervolcano Eruption

The single worst explosion in our geological history occurred at Lake Toba, about 160 kilometers from the epicenter of the 2004 tsunami-producing earthquake. It occurred 71,000 year ago and produced a caldera 100 kilometers long. The Toba super-eruption was the biggest volcanic blast on Earth in the past 2.5 million years, and probably further back than that as well. There were also massive eruptions at Yellowstone 640,000, 1.3 million and 2.1 million years ago. Some theorize that the Toba eruption came close to wiping homo sapiens. They argue the human population shrunk to a few thousand after the event.

Researchers estimate some 2,000-3,000 cubic environmental of rock and ash were ejected from the volcano when it exploded. It was only in 1929 that a Dutch geologist recognized the lake as a caldera. A caldera is essentially a great hole that occurs in the Earth’s surface after a great amount of material has been removed by a massive volcanic eruption. The central part of Yellowstone National Park is caldera—measuring 35-by-45-mile (60-by-70-kilometer)—about the same size as Lake Toba. Eruptions that leave calderas are rare. The one at Toba seems occur every a 400,000 years or so. [Source: Joel Achenbach, National Geographic, March 2005]

According to volcano.oregonstate.edu: “The caldera is 18 x 60 miles (30 by 100 kilometers) and has a total relief of 5,100 feet (1700 m). The caldera probably formed in stages. Large eruptions occurred 840,000, about 700,000, and 75,000 years ago. The eruption 75,000 years ago produced the Young Toba Tuff. The Young Toba Tuff was erupted from ring fractures that surround most or all of the present-day lake. Samosir Island and the Uluan Peninsula are parts of one or two resurgent domes. Lake sediments on Samosir indicate at least 1,350 feet (450 meters) of uplift. Pusukbukit, a small stratovolcano along the west margin of the caldera, formed after the eruption 75,000 years ago. There are active solfataras on the north side of the volcano. [Source: volcano.oregonstate.edu /^]

See Separate Article: TOBA SUPERVOLCANO ERUPTION 71,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

Activities in the Lake Toba Area

Activities that can be enjoyed include hiking, swimming, sailing and visiting villages of the area’s main ethnic group, the Batak. In Parapat, where transport from Medan arrives, there are facilities for swimming, water skiing, motor boating, canoeing, fishing and golf. From Parapat take a leisurely walk in the beautiful Naborsahon River valley where you’ll see spectacular bougainvilleas, pointetties and honeysuckle flowering all year round.

Many people stay on the island of Samosir in the middle of the lake, which is not really an island but an isthmus connected to shore of the lake opposite from where you arrive. From Samosir, take a trip inland and explore the two smaller lakes (Sidihoni and Aek Natonang Lake). Or trek into the central highlands. It’s best to ask your hotel or locals for a recommendation for a route as, depending on the time of year, tracks can be muddy and slippery.

At Tuktuk on Samosir are a large number of accommodation and restaurants that also rent out bikes, motorbikes and books. You can also exchange the books with the ones you bring. The more upmarket hotels are located along the lake’s shore with an exclusive beach for guests. Watersports such as canoeing, jetskiing, waterbikes, or swimming and fishing are best pastimes here.

Bike or ride motorbike across the countryside around Samosir. Trek up the mountain to the plateau, to the village of Tele, the vantage point to absorb the grand scenery on Lake Toba. Or watch the serene sunrise and sunset over this spectacular scenery. You can also try paragliding from Bukit Siulakhosa, for added excitement and unforgettable photographs. The Bukit Betha and the Open Stage at Tuktuk Siadong are also often used as arena for athletics, downhill biking, motor cross and other nature sports.

Sipiso-piso waterfall can be viewed from a gazebo on top of one of the hills near the town of Tongging. Lcated on the North side of Lake Toba, 24 kilometers from Kabanjahe. This long but narrow waterfall drops 120 meters into an impressive gorge below. From Berastagi it is a 45 minute to Sipiso-Piso waterfall.

Parapat

Parapat (four hours by bus from Medan) is main resort town and gateway to the Lake Toba area. Built on a hillside on eastern shore of Lake Toba, it is overdeveloped and oriented towards Asian tourists and rich people from Medan. There is a busy Saturday market by the ferry. Many restaurants and shops are located o SM Raja (the Trans-Sumatran Highway). souvenirs such as T-shirts and keychains. There is also a traditional market which happens twice a week selling fruit, vegetables and clothing. From Parapat there is a frequent ferry to Samosir, where most Western tourists go.

Parapat occupies a small, rocky peninsula jutting out into the lake. On the way down to Parapat from the hill town of Berastagi you will get some spectacular views as the lake first comes into sight and the road winds its way down the mountain closer to the shoreline. In Parapat live the Batak Toba and Batak Simalungun people who are known as a happy and easygoing people, famous for their lively and sentimental songs. Although the majority have embraced Christianity, ancient beliefs and traditions still persist.

Samosir Island

Samosir Island (inside Lake Toba) fills up about half of Lake Toba. Covering 329 square miles, an area about the size of Singapore, it is the remnant of a small volcano that rose up in the middle of the lake after a large eruption about 50,000 year ago. A close look at a map reveals that Samosir is not really an island.. A narrow isthmus on the west side connects it to the mainland.

Samosir is the original home of the Toba Bataks. Worth checking are villages with the traditional Batak Toba houses. Sometimes local dances and hymn singing are performed. The best villages are on the western side of the island across from the central ridge. There is some excellent trekking around the island. From the top of the islands central ridge, which lies 700 meters above the lake, there are some fantastic views. The original forest are mostly gone. In their place are cinnamon, clove and coffee plantations.

On the east side of the island, the land rises steeply from a narrow strip of flat land along the lake’s water edge climbing to a central plateau that towers above the waters. Cycling up to the plateau passing many traditional villages is an arduous by rewarding pleasant experience. From the road on the plateau there are wonderful panoramic views of the lake’s magnificent blue water.

Towns and Sights on Samosir Island

Regular ferries ply between Parapat on the mainland and the villages of Tomok and Tuktuk on Samosir. As you step down the ferry at Tomok you will be greeted by a row of sounvenir stalls selling an array of Batak handicraft, from the traditional hand-woven ulos cloths to Batak bamboo calendars and all kinds of knick-knacks.

Tomok itself is a traditional village, best known as the gateway and introduction to Samosir. Here is the large stone sarcophagus of chief Sidabutar. Carved from a single block of stone, the tomb dates back to the early 19th century. The front is carved with the face of a singa — — a mythical creature, part water buffalo, part elephant. On the saddle-shaped lid is a small statue of a woman carrying a bowl, believed to represent the wife of the dead chief. Beautifully painted traditional adat houses stand in a neat row, with their backs to the lake, complemented with rice barns facing the houses. The elaborate Batak designs on these houses form leaves and flowers and are typically colored in black, white and red. Tomok, the main town on the east side of Samosir, has a number of traditional Batak houses and graves and tombs.

Further north of Tomok is a small peninsula, known as Tuktuk Siadong, — or simply Tuktuk — best loved for its sandy beaches and beautiful lush scenery. Here the soft lapping blue waters of lake Toba blend with the green pastures where water buffalos graze or work the land. Although offering beaches and opportunities for watersports, yet the air here is cool as it is located high in the mountains. No wonder, therefore, that Tuktuk has become a favorite with tourists, so that here you will find a plethora of small hotels and homestays, restaurants and handicrafts galore.

Further north are the villages of Ambarita and Simanindo. At Ambarita, some four kilometers from Tuktuk are groups of megaliths and 300-year-old stone chairs, said to have been a place where criminals were sentenced and beheaded. At Simanindo, 19 kilometers. north of Tuktuk is the elaborately decorated house of Raja Sidauruk, which is now a museum. Here sigalegale puppet performances are regularly performed. The human-sized sigalegale puppets are believed to be a receptacle for the soul of the deceased at funeral rites. Simanindo also has some well-restored traditional houses. Panguran is a town outside the tourist zone that lies ay the middle of an area with traditional villages and superb scenery.

Tuktuk

Tanjung Tuk Tuk (on the east side of Samosir Island reached by ferry from Parapat) is the a touristy town on Samosir directly across from Parapat. Many tourists stay here. It has a large number of hotels, guest houses, restaurant, bars and souvenir shops. Music performances are regularly held. The town is very cheap. Ferries between Parapat and Tuk Tuk operate roughly once every hour.

Because Tuktuk is popular with many international tourists, finding food is not a problem, since Tuktuk is practically up and running 24 hours a day. In the evening there are still a number of restaurants and cafes open offering Batak bands, dances, and traditional performances. The Batak are famous for their melodious music and strong vocals. Although the majority of Batak are Christian, they show respect towards Muslims by not serving pork at restaurants.

If you are interested in learning Batak cooking, you can take a Batak cooking class in Tuktuk. The handicraft center at Tuktuk has many souvenir shops selling Batak handicrafts, such as the ulos cloth, woodcarvings, Batak bamboo calendars and staffs like those used by former Batak chieftains. Tomok too has plenty of stalls and kiosks selling Batak handicrafts and knick-knacks.

Bataks

The Bataks is the name for a group of sub-societies that live in the rugged highlands and plains around Lake Toba in northern Sumatra. The word Batak is believed to have originally been a derogatory term meaning “primitive” used by lowland Muslims to describe highland people. Today there is little stigma attached to the word. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The Batak homeland in North Sumatra is located on a high, rolling plateau (1,000 meter or 3,280 feet or above sea level) between two parallel volcanic ranges of the 2,000-meter (6,560-foot) -high Bukit Barisan Mountains. The region centers on Lake Toba.

The Batak Toba and Batak Simalungun tribes are the primary indegenous people that occupy the Lake Toba area. They are an easy going group of former head-hunters that are known for their sentimental songs. They enjoy drinking traditional palm wine and many still reside in distinctive Batak Toba house compounds. In Tomok you can visit to the cemetery complex of King Sidabutar. You can learn more traditional Batak life and culture and try traditional weaving at the village of Jangga, about 24 kilometers from Parapat.

At Simanindo, 19 kilometers. north of Tuktuk is the elaborately decorated house of Raja Sidauruk, which is now a museum. Here sigalegale puppet performances are regularly performed. The human-sized sigalegale puppets are believed to be a receptacle for the soul of the deceased at funeral rites. Simanindo also has some well-restored traditional houses.

The Toba Batak believe Lake is the dwelling place of Namborru (the seven ancestor goddesses of Batak Tribe). When Bataks performs a traditional ceremony at they must first pray to to receive permission from Namborru. The best time to see traditional rituals being performed is during the annual Lake Toba Folk Party ceremony in early December, where many ceremonies are performed in respect to the ancestors of the lake. This festival is a colorful celebration of Batak culture, with traditional ceremonies, sporting events and Batak singing and dancing on display.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BATAKS: GROUPS, HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND WERE THEY REALLY CANNIBALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK RELIGION: CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, BURIALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, KINSHIP factsanddetails.com

BATAK LIFE: HOUSES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK factsanddetails.com

BATAK CULTURE: MUSIC, ART, FOLKLORE, CRAFTS AND LIFE-SIZE PUPPETS factsanddetails.com

Batak Museum and TB Silalahi Center

Batak Museum (on the southern shore of Lake Toba) is located in the TB Silalahi Center and is dedicated to the preservation of the cultural values of the indigenous ethnic population of North Sumatra: the Bataks. The complex on Jl.Pagar Batu No.88 Silalahi Village, by the town of Balige and was established by — and is named after — the prominent Batak personality: Tiopan Bernhard Silalahi who has played an important role in North Sumatra’s and Indonesia’s history.

Opened in 2011, the Museum is built on the concept that the ethnic Batak have had a highly developed cultural since ancient times. This is demonstrated by the fact that the Bataks possess their own distinct writing and spoken language, they follow the traditional democratic principals of Dalihan Natolu, and have a sophisticated way of passing down clan or family names. The museum also acts as a unifying symbol of the different Batak clans, namely: the Batak Toba, Batak Simalungun, Batak Mandailing, Batak Angkola, Batak Pakpak/Dairi, and the Batak Karo.

The Museum is has three floors and an open space on ground floor, which is used to display traditional Batak stone sculptures. From the 2nd floor, visitors have magnificent view on the open-space courtyard and Lake Toba and a seven-meter bronze statue of Si Raja Batak or King of Batak.

The 2nd and 3rd floor are the main exhibiting areas of the museum. On display are Ancient Batak’s scriptures, traditional weapons, various jewelry and farming equipment. Of particular interest is collection of ‘Ulos’, the age-old traditional Batak woven cloths. The oldest ‘Ulos’ exhibited here is believed to be 500 years old. The oldest scripture that the museum has dates back to the year 1800.

Museum Batak is considered as one of the most modern museums in Indonesia. The display labels are in both Bahasa Indonesia and English. Within the vicinity of the TB Silalahi Center are other interesting attractions such as: the personal museum of TB. SIlalahi, the Huta Batak, which is an outdoor museum built like a traditional Batak village consisting of three rumahs (houses) and three sopos (storage structures) depicting typical Batak homes, actual scaled replicas of the Rumah Bolon and the Rumah Batak, a convention hall, and a swimming pool. The complex is also completed with visitors facilities such as restaurants, cafeterias, and an art shop. More Information is available at: museumbataktbsilalahicenter.com

Jangga

Jangga (about 24 kilometers from Lake Toba) is an area of native Batak villages. Traditional houses which have remained unchanged through the centuries can be visited and young and old ladies can be observed weaving beautiful ulos cloth. There are also monuments and historical remains left by ancient Batak kings. Traditional Batak houses sit on stilts and have distinctive oversized roofs.

Jangga is most famous for the beautiful ulos cloths which are produced here. Watch the women of the community weave these intricate cloths from inside their booths. Ulos plays an important role in traditional Batak society and are used not only as clothing but presented on ritual occasions such as births, deaths and marriages. In Jangga you will also find rows of traditional houses and see monuments dedicated to Batak kings centuries ago including King Tambun and King Ma nurung monuments.

Jangga Village is located on the edge of Simanuk-manuk Mountain,. It is one of a number of villages of native Bataks in the region including Lumban Nabolon, Tonga-Tonga Sirait Uruk, Janji Matogu, Sihubak hubak, Siregar, Sigaol, Silalahi Toruan Muara and Tomok Sihotang. Travel agents can arrange a homestay for you in the village.

Accommodation and Getting to Lake Toba

There are a range of hotels, bungalows, villas and guesthouses available in Parapat. On Samosir, the majority of hotels are found in Tuk Tuk. Here you can find something to suit any budget and taste. . Tuk Tuk is a great base from which to explore the rest of the island, and the facilities here are comfortable and convenient. Prices for hotels, guest houses and homestays in Tuktuk range from Rp100,000 - to Rp500, 000 a night depending on the type.

Parapat is 176 kilometers from Medan and can be reached in under 6 hours by public bus. The bus has two routes: Medan-Parapat or via Medan-Berastagi and costs approximately 30,000 rupiahs. You can buy a spot in a private air conditioned taxi from Medan to Parapat for 65,000 rupiahs one way. The trip takes around 4 hours. Travel agents in Medan can also organize a rental car plus a driver for you.

You can also take the train that serves Medan - Pematang Siantar, then board a bus from here to Parapat, which takes around 2 hours.Tourist buses also take passengers from Medan to Parapit via Lubuk Pakam, Tebing Tinggi, to Pematang Siantar. Along the route enjoy the panorama of palm oil and rubber tree plantations.

Once you arrive in Parapat, you can catch the ferry to Samosir Island. The ferry goes every hour and a half from 9 — 5pm. The two landing points on Samosir are the traditional village of Tomok, or Tuk Tuk, where the islands hotels and restaurants are concentrated. If you are coming overland from the south via Bukittinggi and Tarutung there is a public bus available.

After you arrive rent a bicycle or a motorbike to explore the lake by taking a drive on the roads running around the edge of the island of Samosir and the rim of the lake.. Although rough and unpaved in places, these road offers some spectacular views of the lake and pass coffee plantations, farms and Batak villages.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Indonesia Tourism website ( indonesia.travel ), Indonesia government websites, UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Japan News, Yomiuri Shimbun, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last Updated in December 2025