BATAKS

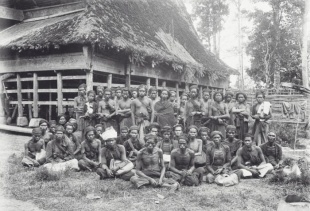

Batak is the name for a group of sub-societies that live in the rugged highlands and plains in northern Sumatra. The word Batak is believed to have originally been a derogatory term meaning “primitive” used by lowland Muslims to describe highland people. Today there is little stigma attached to the word. The name "Batak" also applies to a different ethnic group on the Philippine island of Palawan. The main Indonesian Batak groups are the Toba, Karo, Simalungun, Dairi (Pakpak), Angkola, and Mandailing. The Toba are the only ones that really like the name Batak. The heavily Islamized Angkola and Mandailing don't like the term. Some Batak languages can be understood by Malays and Indonesians but others can not even be understood by other Bataks. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Living in a beautiful part of North Sumatra mostly around Lake Toba and east of it, the Batak people are divided into six main cultures, each with its own language and traditions. Although geographically isolated, the Bataks have a history of regular contact with the outside world. Trade between the highlands and other regions saw the exchange of goods such as salt, cloth and iron for gold, rice and cassia (a type of cinnamon). ~

The Bataks are a Malay people and are regarded as the fourth largest ethnic group in Indonesia after the Javanese, Sundanese and Malays.. Although the Batak groups are closely related they are regarded as separate groups. These groups make up 3.6 percent of the population of Indonesia (about 9 million people), living both in their traditional homelands in Sumatra and elsewhere in Indonesia. Overpopulation in recent decades has forced many Batak to settle in the densely forested piedmont and in the coastal plantation zones to the east and west. The Batak also form a significant portion of the population in the multiethnic metropolis of Medan and can be found in cities throughout Indonesia. According to the 2000 census, the Batak population was 6.1 million, making them Indonesia's fifth largest ethnic group and 3 percent of the population. This figure is nearly double the 1990 census estimate of 3.1 million speakers of the three Batak languages. A more recent estimate puts the number at nine million. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

“Batak” (pronounced BAH-tahk) groups inhabit the interior of Sumatera Utara Province, south of Aceh and are mostly Christian, with some Muslim groups in the south and east. Historically isolated from Hindu-Buddhist and Muslim influence, they bear closer resemblance culturally to highland swidden cultivators elsewhere in Southeast Asia, even though most practice wet-rice farming. [Source: Library of Congress]

RELATED ARTICLES:

BATAK RELIGION: CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, TRADITIONAL BELIEFS, BURIALS factsanddetails.com

BATAK SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, KINSHIP factsanddetails.com

BATAK LIFE: HOUSES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK factsanddetails.com

BATAK CULTURE: MUSIC, ART, FOLKLORE, CRAFTS AND LIFE-SIZE PUPPETS factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS IN SUMATRA factsanddetails.com

SUMATRA: HISTORY, EARLY HUMANS, GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE factsanddetails.com

LAKE TOBA AREA: BATAKS, SAMOSIR ISLAND AND THE TOBA SUPERVOLCANO ERUPTION 71,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

Batak Language

The Bataks is the name for a group of sub-societies that live in the rugged highlands and plains around Lake Toba in northern Sumatra. The main Indonesian Batak groups are the Toba, Karo, Simalungun, Dairi (Pakpak), Angkola, and Mandailing. The Toba are the only ones that really like the name Batak. The heavily Islamized Angkola and Mandailing don't like the term. Some Batak languages can be understood by Malays and Indonesians but others can not even be understood by other Bataks.

Batak language-dialects are divided into three mutually unintelligible groups: 1) Toba-Angkola-Mandailing, 2) Karo-Dairi, and 3) Simalungun. In the past, intercommunication was possible because many Bataks knew languages other than their own, including Malay, which could be used with non-Bataks. Today, widespread mastery of Bahasa Indonesia facilitates intercommunication. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Children take the clan (marga) names of their fathers as surnames. Batak religious specialists have long used a script of Indian origin to record occult knowledge, and the letters vary slightly among the six Batak groups."

Each tribe has a Batak greeting. The Batak tribe is famous for its greeting, Horas, but there are two less popular greetings in the community: Njuah Mejuah Juah Juah. The Horas greeting is specific to each tribe:

1) Pakpak: "Njuah-Mo Juah Banta Karina!"

2) Karo: "Mejuah-Juah We Krina!"

3) Toba: "Horas Jala Ma On Hita Saluhutna Gabe!"

4) Simalungun: "Horas banta Haganupan, Salam Habonaran Do Bona!"

5) Mandailing and Angkola: "Horas Tondi G Tondi Matogu Madingin Pears, Vegetables Matua Bulung!" [Source: ibdo.blogspot.jp]

Batak Groups

Simalungun Batak live in Sumatera Utara Province, Simalungun, Serdang Bedagai, Deli Serdang, and Kota Pematang Siantar regencies; area northeast of Lake Toba, south of Medan. According to Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 1,691,000 and their primary language is Batak Simalungun About 65 percent are Christians, with Evangelicals comprising 10 to 50 percent of the total number of Christians. Around 1990 there were 1.2 million Simalungun, east of Lake Toba. [Source: Joshua Project]

Silindung Batak live in Central Sumatera Utara Province, Simalungan, Asahan, Labuhan Batu Utara, Toba Samosir, Tapanuli Utara, Samosir, Humbang Hasundutan, and south Tapanuli Tengah regencies; Samosir island; east, south, and west of Lake Toba. According to Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 585,000 and their primary language is Batak Toba. About 97 percent are Christians, with Evangelicals comprising 10 to 50 percent of the total number of Christians.

Pakpak Batak live in Sumatera Utara Province, Dairi, Pakpak Barat, Samosir, Humbang Hasundutan, and Tapanuli Tengah regencies, southwest of Lake Toba, area around Sidikalang town, south to coast; also in Aceh Province, Aceh Singkil regency. According to Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 59,000 and their primary language is the Pakpak dialect of Batak Dairi. About 70 percent are Christians,with Evangelicals comprising 5-10 percent of the total number of Christians.

Dairi Batak live in Sumatera Utara Province, Dairi, Pakpak Barat, Samosir, Humbang Hasundutan, and Tapanuli Tengah regencies, southwest of Lake Toba, area around Sidikalang town, south to coast; also in Aceh Province, Aceh Singkil regency. According to Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 2,109,000 and their primary language is Batak Dairi. About 79 percent are Christians, with Evangelicals comprising 10 to 50 percent of the total number of Christians. Around 1990 there were 1.2 million Dairi west of the Lake Toba.

Toba Batak

Toba Batak live in Central Sumatera Utara Province, Simalungan, Asahan, Labuhan Batu Utara, Toba Samosir, Tapanuli Utara, Samosir, Humbang Hasundutan, and south Tapanuli Tengah regencies; Samosir island; east, south, and west of Lake Toba. According to Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 2,559,000 and their primary language is Batak Toba. About 97 percent are Christians, with Evangelicals comprising 10 to 50 percent of the total number of Christians. Around 1990 there were 2 million Toba, living around Lake Toba, on Samosir Island, and in the highlands to the south. [Source: Joshua Project]

Most Batak Toba who live in their traditional homeland are farmers. Many of those who live outside their traditional homelands are angkot (minibus) drivers, coach drivers, lorry drivers, chauffeurs and loan sharks. Many of the educated Batak Toba who live outside their traditional homelands are teachers, lecturers or lawyers.

The Batak Toba and Batak Simalungun tribes live around Lake Toba. The large island of Samosir in the middle of the lake is said to be the original home of the Toba Batak. Scattered around the island are traces from ancient times, including stone tombs and traditional villages, such as at Ambarita which has a courtyard with stone furniture where convicts were tried and beheaded. Tomok is famous Batak handicrafts such as distinctive red and black hand-woven shawls called ulos — that are still used today at important life-cycle occasions—rattan Batak calendar and woodcarvings. The lake itself is believed to be the dwelling place of Namborru (the seven ancestor goddesses). When a Batak tribe performs a traditional ceremony around the LAKE, they must first pray for permission from Namborru.

“Horas” is the traditional Toba Batak greeting. It is delivered with much fanfare to visiting tourists. Toba has a strong Christian tradition while southern Batak areas or more Islamic. Many of Christians in the Toba area love singing at church. The first missionaries to arrive in the Lake Toba area in 1834 were eaten because of their "Westerner's arrogance." A German Lutheran missionary who arrived in 1862 had more success. He converting the Batak after learning the Batak language and teaching the Bataks Christian songs.

It has been said the Toba Bataks, who live on Samosir island in the middle of Lake Toba, hunted heads and ate their victims. Andreas Lingga, the director of the Batak Museum told National Geographic, "My grandfather said [the palm] was the most desired part. It wasn’t the sweetest, but the elders thought palm flesh had medicinal properties." Toba Bataks no longer eat human meat but they enjoy dog stew. Some of the headhunting and cannibalism stories are based less on reality than a desire to conjure up interesting stories for tourists.

Karo Batak

Karo Batak live in Sumatera Utara Province, Langkat, Deli Serdang, Karo, and Dairi regencies west and northwest of Lake Toba; south, small border area in Tapanuli Tengah regency; also in southern Aceh Province, small enclave in Aceh Tenggara regency; south, parts of Kota Subulussalam, Aceh Selatan, and Aceh Singli regencies. According to Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 1,019,000 and their primary language is Batak Karo. About 70 percent are Christians, with Evangelicals comprising 10 to 50 percent of the total number of Christians. Around 1990 there were 600,000 Karo northwest of Lake Toba. [Source: Joshua Project]

The Karo Batak are the indigenous inhabitants of the Karo Highlands in North Sumatra. Most live in Karo Regency, with significant populations also found in Dairi Regency, Deli Serdang, Medan, Langkat Regency, and parts of Southeast Aceh. Traditionally, Karo Batak communities are organized in villages known as kuta. Their ancestral homeland encompasses the regencies of Karo and Dairi, along with adjoining areas of Deli Serdang, Langkat, and Southeast Aceh.

Those who remain in the highlands are predominantly farmers, cultivating vegetables, fruits, and other crops well suited to the cool upland climate. Many Karo Batak, however, have migrated to major cities such as Jakarta, Bandung, and Surabaya. Outside their homeland, some men find work as minibus (angkot) drivers, private chauffeurs, bus or truck drivers, while others take up informal or marginal occupations. Karo Batak who pursue higher education often leave the highlands to work as teachers, lecturers, or other professionals, maintaining ties to their home villages while participating in Indonesia’s urban economy.

Angkola Batak

Angkola Batak live in Sumatera Utara Province, Tapanuli Tengah, Tapanuli Selatan, Tapanuli Utara, Padang Lawas Utara, Padang Lawas, Labuhan Batu, and Labuhan Batu Selatan regencies; inland from near Sibolga city south towards Padangsidempuan, east to Binanga towards southern provincial border, northeast towards the Strait of Malacca. According to Joshua Project their population in the 2020s was 1,274,000 and their primary language is Batak Angkola, Around 90 percent are Muslims. Around 1990 there were 750,000 Angkola.

The Angkola Batak are a Batak subgroup whose ancestry reflects historical ties with both the Batak Toba and Mandailing peoples. In Sipirok, the largest town in South Tapanuli Regency, nearly half of the population traces its descent to migrants from North Tapanuli who moved south in the fourteenth century, many of whom belong to the Siregar clan. Prominent Angkola Batak clans include Nasution, Siregar, Harahap, Pohan, Hasibuan, and Daulay, alongside several clans more commonly associated with Batak Toba, such as Pasaribu and Hutagalung. Around 1990 there were 400,000 Mandailing and 800,000 Alas-Klue,

Most Angkola Batak live in South Tapanuli Regency, as well as in the cities of Padangsidimpuan and Sibolga. Significant numbers have also migrated to larger urban centers, including Medan, Padang, Pekanbaru, Batam, Jakarta, Bandung, and Surabaya, and some have settled overseas.

In their homeland, most Angkola Batak are engaged in agriculture. Those living in Padangsidimpuan and Sibolga are often involved in urban informal occupations such as pedicab or motorized rickshaw driving. Migrants in larger cities commonly work as minibus, truck, or bus drivers, or as private chauffeurs, while a minority are employed in informal security or street-level roles. Angkola Batak who attain higher levels of education frequently pursue professional careers outside their homeland, becoming teachers, doctors, lawyers, and other skilled professionals, while maintaining strong social and cultural ties to their communities of origin.

Toga Batak

In Batak culture, “Toga”—a term meaning “ancestor” or “father”—refers to the founding male ancestor from whom a clan (marga) traces its origin. Across North Sumatra, Batak clans such as Simanjuntak, Nainggolan, Sihombing, and Sinaga identify a specific Toga as the patriarch who established their lineage. This concept lies at the heart of the Batak patrilineal system, in which descent, identity, and inheritance are traced through the male line, with the Toga marking the starting point of a clan’s genealogy.

Togas play a central role in shaping Batak social life and cultural identity. They define clan membership and regulate marriage rules, most notably the prohibition against marrying someone from the same clan, since all members are considered descendants of a common ancestor. The memory of a Toga is preserved through oral histories, rituals, and clan gatherings, which reaffirm shared ancestry and social obligations among descendants.

The importance of the Toga is also expressed materially and institutionally. Many clans construct large stone monuments (tambak) to honor their founding ancestors, symbols of continuity, prestige, and collective memory. In addition, clan-based associations—such as organizations formed by descendants of a particular Toga—work to maintain genealogical records, organize ceremonies, and uphold traditional values. Through these practices, the legacy of the Toga continues to anchor Batak society, linking present-day communities to their ancestral past.

Early Batak History

The Bataks are believed to have descended from tribal people who lived in Burma, Thailand and southern China. Language and archaeological evidence suggests that the Austronesian-speaking people of Taiwan have moved to the area the Philippines and Indonesia about 2,500 years ago. When the Bataks arrived in Sumatra they migrated inland and established communities around Danau Toba (Lake Toba). The Batak speak Austronesian languages. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The Bataks were regarded as fierce warriors and head-hunters. Marco Polo may have been describing them when he referred to the people in Sumatra as "such as beasts...For I tell you quite truly that they eat flesh of men." The Batak often feuded among themselves and were reportedly reluctant to build bridges or well-maintained trails because they were intensely distrustful of their neighbors and worried about raids. The ritual eating of human flesh—of killed enemies and people that broke taboos—is said to have endured among the Toba Batak until 1816. ~

Rugged and thickly forested mountain and the Batak's reputation for fierceness deterred coastal-dwelling people from venturing into the highlands. As a result, Batak villages remained largely independent from outside rule and were free to wage war among themselves. Although the Batak were connected to the outside world through trade—especially in benzoin wood used to make incense—their society was only lightly affected by the Hindu-Buddhist influences that reshaped nearby regions. These ideas reached the highlands only indirectly, through small coastal kingdoms or Tamil merchant groups. Like many interior peoples in Southeast Asia, the Batak were feared by lowland societies as headhunters and were also widely rumored to be cannibals. Such stories greatly exaggerated reality (See Cannibalism Below). [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Research on Karo traditions by JH Neumann, based on transcriptions of oral literature and a history written in local script on the origin of the clan Kembaren Pagaruyung in Minangkabau suggests that the Karo existed as far back as the 14th century based on the number of Karo surnames derived from Tamil language. Tamil people were major traders on Sumatra until the 14th century when they were driven out by the Minangkabau. [Source: ibdo.blogspot.jp]

Anthropologist RW Liddle has argued that prior to the 20th century there were no ethnic groups as coherent social units in northern Sumatra and social interaction in the area was limited to relationships between individuals, between groups of kin, or between villages. He argued there was almost no consciousness to be part of the larger social or political units. Others have suggested that the emergence of the Batak identity emerged in colonial times. In his dissertation J. Pardede argued that the term "Batak Land" and "people of Batak" was created by outsiders. Siti Omas Manurung , the wife of the son of a Toba Batak priest said that before the arrival of the Dutch, all good people Karo and Simalungun recognize him as Batak. There is a myth that Pusuk Buhit , one of the peaks in the west of Lake Toba , was the "birthplace" of the Batak people.

Later Batak History

The first time the outside world heard about the Bataks was in an account in 1783 by the British traveler William Mardens who described them as a cannibalistic people that had a highly developed culture and a sophisticated writing system. The Aceh battled with the Bataks and tried to convert them to Islam but Islam did not make much head way in the Batak regions until the 1820s. The Dutch and Western missionaries had better luck introducing Christianity. The Dutch arrived in the area in the 1850s and encountered some armed resistence from the warrior chief Sisingamangaraja XII and didn’t gain control of the region until 1910 after Sisingamangaraja XII died. Some Batak were involved in pro-Indonesian and anti-Dutch activities before World War II. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Islamic influence in the Batak highlands remained limited until the early nineteenth century, when the Padri movement—aimed at purifying Minangkabau society of pre-Islamic practices—spread into the southern Batak regions. This expansion took the form of armed campaigns to force the conversion of the Mandailing and Angkola peoples. Dutch colonial forces intervened against the Padri and followed them into southern Batak territory; by the 1840s, the coastal areas below the Batak highlands were under Dutch control. Although there was no unified Batak resistance, the Dutch only fully subdued the Batak peoples after a series of hard-fought military campaigns in the second half of the nineteenth century. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

In 1824, two British Baptist missionaries, Richard Burton and Nathaniel Ward, walked inland from Sibolga Batak. After three days of walking, they reached the plateau Silindung and settled there for two weeks and made direct observations of Batak society. In 1834, Henry Lyman and Samuel Munson from the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions visited Batak territory in Sumatra. In 1850, the Board of the Dutch missionaries commissioned Neubronner Herman van der Tuuk published grammar books and dictionaries in the Batak and Dutch.[Source: ibdo.blogspot.jp]

The first German missionaries arrived in the valley around Lake Toba in 1861. A mission was set up by Dr. Ludwig Ingwer Nommensen of the Rhenish Mission Society in 1862. The New Testament was translated into Toba Batak language by Nommensen in 1869. Some Toba and Karo communities absorbed Christianity quickly and made Christianity the cultural identity at the beginning of the 20th century. By 1900, most Toba had converted to Protestant Christianity, due largely to Nommensen’s efforts to remain independent of Dutch colonial authority and his role as a doctor, teacher, and mediator. The Protestant Church of Batak Christians (HKBP) was established in Balige in September 1917. In the late 1920s, a school nurse provides care training to midwives there. Later in 1941, the Karo Batak Protestant Church (GBKP) was established. ^^

Over time Dutch influence increased with the construction of the first road into the highlands in 1908 being a major milestone. This penetration met resistance in several forms: armed religious movements blending old and new beliefs, Karo and Simalungun suspicion of Christianity as a tool of colonialism, and the eventual creation of an autonomous Batak church free from European missionary control.Education provided by mission schools gave the Batak important advantages, enabling them to take up commercial and teaching positions throughout the Dutch East Indies and later to play prominent roles in Indonesia’s national leadership from the independence period onward. Today, the Batak regions are rapidly developing as agricultural hinterlands for the oil- and rubber-producing northeast Sumatran coast, the city of Medan, and even markets in Singapore and Malaysia. The Karo and Toba highlands have also become major tourist destinations, ranking just behind Bali and Yogyakarta in popularity. ^^

Batak Cannibalism

Ritual cannibalism has been reported among Batak to strengthen a person’s Tondi. In particular, blood, heart, palms, and soles of the feet are considered as rich Tondi. As early as the 9th century, an Arab text mentions that Sumatra’s inhabitants eat human flesh. During his visit to east Sumatra from April to September 1292, Marco Polo said he met coastal people that described inland people as "man-eaters". Niccolò Da Conti (1395-1469), a Venetian who spent most of 1421 in Sumatra, wrote: "In this part of the island, called cannibals living Batech fight constantly to their neighbors”. [Source: ibdo.blogspot.jp +++]

The first Europeans to venture into Batak territory were missionaries, who began to explore the remote inland region in the late 18th century. Missionaries would send reports home of a fierce and defiant local society with frequent mentions of cannibalism. Today anthropologists believe this was a rare form of capital punishment that may have seemed more common than it actually was as many Batak kept the bones of their tribal ancestors which may have been mistaken by outsiders as grisly trophies.

In 1820 Thomas Stamford Raffles studied the Batak and their rituals, and laws regarding the consumption of human flesh. He stated that: "One thing that is common where people eat their parents when too old to work, and for certain crimes a criminal would be eaten alive ...The flesh eaten raw or roasted, with lime, salt and a bit of rice". The German physician and geographer Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn, visited the Batak lands in 1840-1841. Junghuhn say about ritual cannibalism among the Batak (which he called "Battaer"). He said in a a friendly Batak village he was offered the meat of the two prisoners who had been killed the day before. +++

Oscar von Kessel visited Silindung in the 1840s and said he observed the ritual cannibalism in which a convicted adulteress and eaten alive. Von Kessel stated that cannibalism was regarded by the Batak people as an act of law, and its application was restricted to a very narrow range of crimes: namely theft, adultery, espionage, and treason. Salt, red pepper, and lemon were given by the victim's family as a sign that they accepted the decision and would not take out revenge. +++

Ida Pfeiffer visited the Batak in August 1852. Although he did not observe any cannibalism, he was told that: "Prisoners of war were tied to a tree and beheaded at once, but the blood is carefully preserved for a drink, and sometimes made into a sort of pudding with rice. Body parts are then distributed: ear, nose, and feet are the exclusive property of the king, in addition to a claim for some others. Palms of the hands, feet, head meat, heart, and liver, is a typical dish. The meat usually is roasted and eaten with salt. The women were not allowed to take part in a great public dinner ". +++

In 1890, the Dutch colonial government banned cannibalism in the area of their control. Rumors of Batak cannibalism survived until the beginning of the 20th century, and it seems likely that the custom had been rarely performed since 1816 due to the influence of religion in society Batak migrants. +++

Batak Cannibalism a Myth?

British traveller William Marsden astonished the 'civilised' world in 1783 when he returned to London with an account of a cannibalistic kingdom in the interior of Sumatra which, nevertheless, “had a highly developed culture and a system of writing." Research by Professor Masashi Hirosue, of Rikkyo University in Tokyo suggests the image of "Batak cannibalism", or "anthropophagy” was created. [Source: Professor Masashi Hirosue Rikkyo University, Tokyo,, "European Travelers and Local Informants in the Making of the Image of “Cannibalism” in North Sumatra" published in Japan in 2005 in the academic journal "The Memoirs of the Toyo Bunko"|=|]

Hirosue wrote: “North Sumatran coastal rulers, their entourages and local chiefs were the primary sources of stories about "cannibalism" among the inland people. The north Sumatran case suggests that by means of "cannibalism" rumours, coastal rulers were better able to control local trade with foreign merchants by frightening them out of making direct contact with inland people. Then after those coastal rulers were subjected to European colonial rule during the nineteenth century, it was inland chiefs who took up the campaign to advertise "cannibalism" among their villagers, for the purpose of appealing to foreigners the importance of their role in mediating between foreigners and the local "cannibals"." |=|

Marco Polo visited Sumatra, but stayed in coastal ports, never traveling inland. All his stories were provided by local informants: "Polo was so fearful of "cannibals" among the inland people that he stuck to the coast and even constructed defensive fortifications there. However, in due course the local people came to trust the visitors. Polo was unable to verify the existence of "man-eaters". Before arriving at Samudra, he also refers to inland "cannibals" in the north Sumatran port of Perlak, where, according to his account, some of the coastal inhabitants had just become Muslims." (Hirosue, 2005)

Coastal rulers created rumours to stop foreigners from making direct contact with the inland people and monopolise their position. Hirosue wrote: "No matter how widely the rumours of "anthropophagy" spread among foreign travelers, coastal rulers guaranteed their safety while in the ports under their jurisdiction. Those travelers who were reluctant to come into direct contact with inland people for fear of "cannibalism" chose to stay in the coastal entrepots, like Marco Polo, who even constructed bulwarks to protect himself. It was in this way that coastal rulers played a crucial role of intermediary between foreign visitors and the inland people...In order to attract foreign visitors, coastal rulers needed to make close connections with the inland people nearby to guarantee a steady supply of forest, mineral, and food products...It was in this way that the ruler of Pasai on the coast became a mediator between the inland Sumatran world and the Islamic world, not vice versa." |=|

At the same time, it appears that coastal rulers didn't want the inland people making contact with the foreign travelers, and probably portrayed foreign travelers as dangerous, diseased, slave-hunters: “An agreement was made between the chiefs of the hinterland nearest to Barus and the first king of Downstream Barus concerning the intrusion of outsiders, to the effect that they would fight against all enemies from the sea, except the Malay people, and from the inland, except the Batak people. To the hinterland people, foreigners were very dangerous beings, because they often brought in sickness while hunting them as slaves. The Barus case suggests that the coastal ruler took responsibility for defending local hinterland people against outsiders from the sea in return for a stable supply of hinterland commodities and the defense of his rear." |=|

This created a symbiotic relationship between the coastal rulers and inland people: "This is the social context within which stories of "anthropophagy" became very important for both the coastal rulers, who needed constant supplies of inland products and the hinterland people who needed to defend themselves against intrusion by outsiders. As a matter of fact, rumours of "cannibalism" tended to be more rampant in areas such as north Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, where geographically foreigners could have made contact with inland people more easily, as compared to south Sumatra and Java, where hinterland people generally lived far away from the coast." |=|

Reports of Batak Cannibalism During the Dutch and British Colonial Periods

Batak chiefs understood that Europeans feared the reputation of inland Batak cannibals, and so created stories as evidence of their credentials as "genuine" Bataks: Professor Masashi Hirosue wrote: "In 1823, the English East India Company sent J. Anderson, a staff member at Penang to north Sumatra in order to expand British trade networks...He was welcomed by a powerful Batak chief, who, according to Anderson, held authority over twenty villages...The chief spoke to Anderson in fluent Malay with a friendly tone...Anderson asked the chief about the custom of "cannibalism" in the area. The chief then ordered a villager to bring the skull of a victim whom he said had been eaten six days previous. Anderson was strongly impressed by the chief's explanation that the corpse had been devoured in about five minutes. However, the chief graciously offered to play an intermediary role in any further relations between the Company and the Batak "cannibals." [Source:Professor Masashi Hirosue Rikkyo University, Tokyo,, "European Travelers and Local Informants in the Making of the Image of “Cannibalism” in North Sumatra" published in Japan in 2005 in the academic journal "The Memoirs of the Toyo Bunko"|=|]

They even claimed cannibalism in the name of capitalism: "In 1824 Lieutenant-Governor of Bengkulen, Thomas Stamford Raffles, sent two Baptist missionaries to Silindung in the hinterland of Tapanuli, in order to make direct contact with the inland people. The two missionaries were welcomed by a local Batak chief who occasionally visited Tapanuli for trade and invited them to stay in his village.....They also had occasion to ask the chief about whether or not he had eaten human flesh. The chief replied that he and his villagers had executed and eaten the twenty robbers who had occasionally attacked traders between Silindung and Tapanuli the year before, suggesting that his form of "cannibalism" was being done in a righteous effort to defend the trade economy." |=|

When Dutch began appointing Dutch-educated Bataks as local district chiefs, there was no more role for the intermediaries, and stories of cannibalism lost their power: Hirose wrote: "Furthermore, from about 1915 on, the colonial government began appointing to the posts of district and assistant district chief (demang, assistent demang) Batak officials who had been educated at the Training School for Native Chiefs or had been working directly under Dutch colonial officials, giving them positions above the local Batak chiefs...The Batak chiefs who had played an intermediary role between the local people and the Dutch began to be removed from the important political scenes and were transformed into mere messengers of the colonial government. Finally, after the Dutch put the Batak region under their control, the colonial government prohibited "cannibalism," which consequently passed into the realm of Batak historical tradition...The basic reasons for the disappearance was...the loss of the intermediary (informant) status held by Batak local chiefs and their replacement by colonial district and sub-district chiefs who were allowed make direct contact with local people in the performance of their duties. As local chiefs lost their importance as mediators, their stories about "cannibalism" lost their meaning." |=|

Similar stories occured in similar contexts around the world "It is also interesting that the same type of rumours once flourished in other areas, like Latin America, Africa and Japan (in the later part of the thirteenth century, according to Marco Polo in a historical context similar to Sumatra. These other areas were also well-known for precious mineral deposits, and there were also locations where it was generally difficult for foreigners to directly trade with inland producers without some local intermediary." |=|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025